For the USSR Championship in alpinism in the class of high-altitude and technical ascents.

Peak 26 Baku Commissars via the south wall.

Sports team of Tomsk Regional Committee for Physical Culture and Sports.

Team captain and coach (G. Andreev), Tomsk, 1969.

Report

On the ascent of Peak 26 Baku Commissars via the south wall.

1. Geographical Location and Sports Characteristics of Peak 26 Baku Commissars

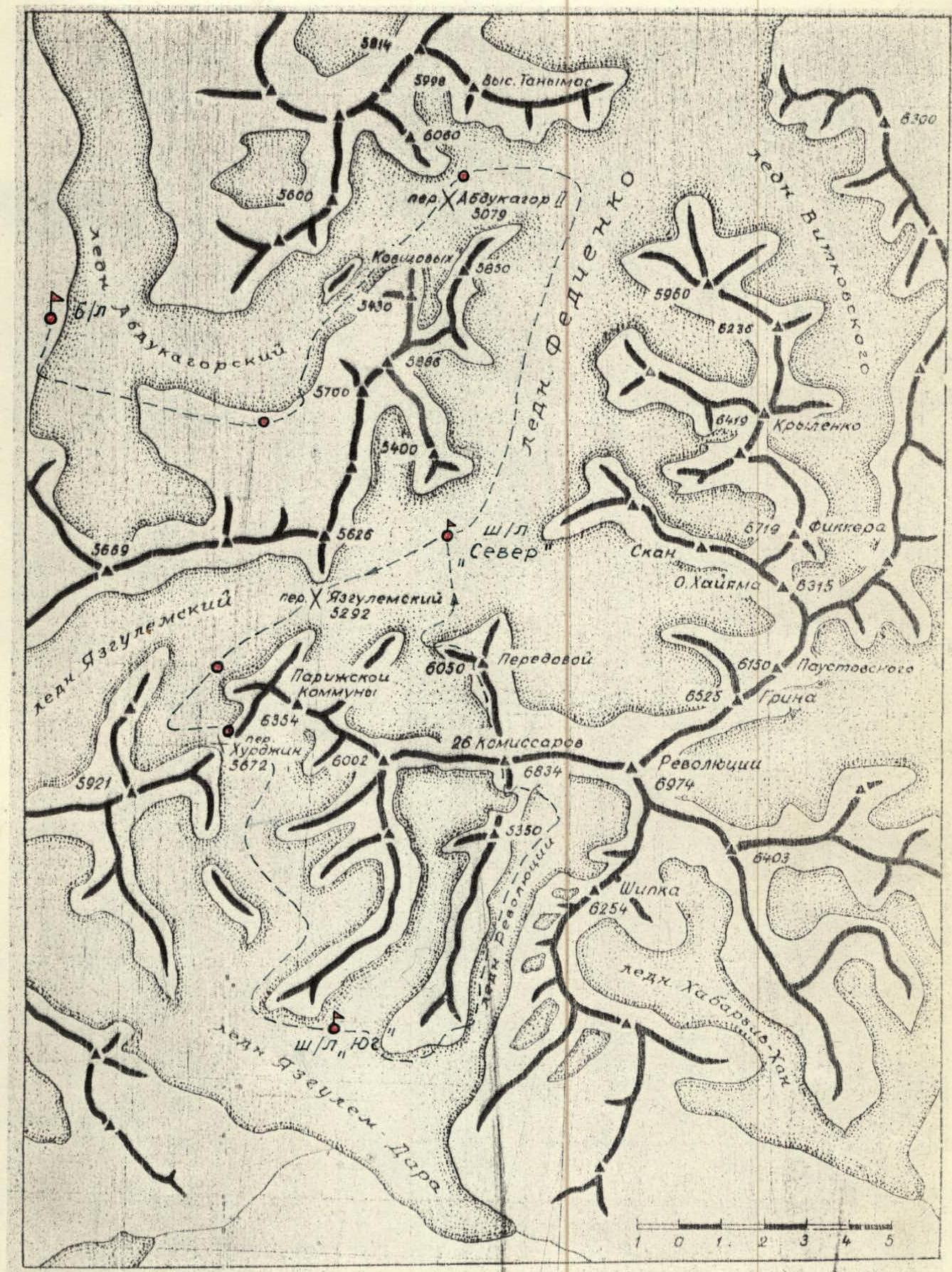

Peak 26 Baku Commissars, with a height of 6834 m, is centrally located in the Yazglem Ridge, which borders the Fedchenko Glacier to the south. The ridge, which descends steeply to the glacier, is at least 10–15 km long, with an average height of 6400–6800 m. The slopes are heavily covered with ice and snow. To the east, the Peak Revolyutsii (6974 m) rises, merging with Peak 26 Baku Commissars through a slight depression.

In the upper reaches, the Fedchenko Glacier has a nearly imperceptible slope over a distance of 10–12 km, from its beginning to the confluence with the Vitkovsky Glacier, opposite the Abdukagor II pass, and is covered with a thick layer of snow. Along the left bank of the glacier lies the Akademiya Nauk Ridge, which is relatively low in this area. The opposite side is significantly more imposing, with many peaks above 6000 m, the highest being Peak Fikкера at 6719 m.

From Peak 26 Baku Commissars, a sharply defined ridge descends northward, along which a pioneering ascent was made in 1957 by a group led by E. Tamm. Since then, several ascents have been made to the summit from the north, and in 1964, an ascent was made from the west during a traverse by a team from the Chelyabinsk Regional Sports Council of the peaks: Peak Paris Commune — Peak Revolyutsii.

At the level of the western edge of Peak Paris Commune lies the Yazglem Pass, from which the Yazglem Glacier flows smoothly to the southwest.

From Peak Paris Commune, the Yazglem Ridge gradually turns south. In the first depression of the ridge lies the Khurdжин Pass (5672 m), leading to the upper reaches of one of the many tributaries of the Yazglem-Dara Glacier on the southern side of the ridge. The southern side of the ridge, facing Bartang, presents an even more grandiose panorama than the northern side, characterized by a greater drop in height of about 1 km, sharp dissection, and narrow spurs with jagged ridges.

Fig. 1. Schematic map of the ridges in the upper reaches of the Fedchenko Glacier and Yazglem-Dara Glacier. (The area of the Yazglem-Dara Glacier was mapped by G. Andreev).

The Yazglem-Dara Glacier is formed by icefalls and lateral tributaries, which merge to form the main glacier. Only one tributary, the Revolyutsii Glacier, is calm, entirely covered with rock debris from the large southern walls of Peaks 26 Commissars and Revolyutsii. Climatic conditions in this area are such that the Yazglem-Dara Glacier is one of the retreating glaciers, with its tongue at an altitude of 3700 m and a maximum length of about 15 km.

From the south, Peak 26 Commissars appears as a massive rock tower. Its southeastern and southwestern walls form an outer corner resembling a ridge, from the lower part of which a rocky spur extends southward, with a highest point at 5350 m.

When choosing the route up the south wall, our choice fell on this ridge.

The significant height difference, the uncharted nature of the route, its logical progression, and technical complexity were the primary motives for our choice.

2. Climbing Conditions

a) Relief. The sharply defined contours of the peaks, sheer walls with significant height differences (up to 2.5–3 km), free from snow, and sharp ridges with large depressions are characteristic of the peaks in the Yazglem-Dara Glacier area, particularly Peak 26 Baku Commissars. The rocky relief is favorable for climbing, although the rocks, mainly composed of schist and marble, are heavily weathered, and rockfalls are common, requiring careful study of the relief when choosing a route.

The route up the south wall of Peak 26 Baku Commissars from the Revolyutsii Glacier has a height difference of 2464 m and an average steepness close to 65°. The route features diverse relief due to the change in rock formations, marked by rock belts of different colors, as well as lengthy ice sections. The steepness and technical complexity of the route increase with altitude.

b) Weather. In July-August, weather conditions are generally favorable for climbing. However, during this period, there are prolonged periods of bad weather with strong winds, snowfalls, and low temperatures. At an altitude of 5000 m, nighttime temperatures drop to –15°C, although daytime temperatures in sheltered areas can rise to +15°C. At altitudes of 6000 m and above, both nighttime and daytime temperatures are significantly lower. A period of bad weather from July 25 to August 1, with heavy snowfalls, particularly in the upper reaches of the Fedchenko Glacier and on the Khurdжин Pass, significantly complicated the organization of camps. A subsequent period of bad weather starting on August 17 caught the assault group on their descent and did not cause significant issues.

c) Remoteness from populated areas and exploration of the area. The Yazglem-Dara Glacier area is perhaps the most remote region of the Central Pamir, which explains why the first mountaineering expedition (CSKA) entered this area only last year.

Approaches to the valley from Bartang are lengthy and complex, making them feasible only for an expedition supported by helicopters for a significant period. The route from the upper reaches of the Fedchenko Glacier is also challenging, involving crossing three high-altitude passes with deep snow and icefalls, with significant altitude gain and loss. Our expedition undertook this difficult and lengthy path.

The area has been largely underexplored until recently. There is only a geological description by geologist G.L. Ktsyn in 1932 in the TKЭ proceedings and a brief description in "Tourist Trails" in 1962 by a group of tourists. In 1967, our group conducted an alpine reconnaissance of this area and achieved a first ascent of Peak 6254 m, named Peak Shipka in 1968. In 1968, a CSKA expedition operated in this area.

3. Reconnaissance and Supply Drops

-

At the beginning of September 1967, following an ascent of Peak Patkhор, we conducted a reconnaissance of the area to assess the possibilities of climbing Peaks 26 Baku Commissars and Revolyutsii from the south. We decided to focus on Peak 26 Baku Commissars.

-

From July 10 to August 6, 1969, the entire expedition team worked on establishing a base camp (4000 m) near a lake on the lateral moraine of the Abdukagor Glacier. From the geologists' settlement — Dalniy, where all expedition cargo was transported by car from Vanch, 2 tons of equipment and supplies were dropped by helicopter on July 15 onto the Abdukagor II pass. The cargo was then transported under the Khurdжин Pass on specially constructed sleds made of duralumin and then carried to the Yazglem-Dara Glacier in backpacks. During this period, we established: a "North" assault camp under the northern slopes of Peak 26 Baku Commissars, a cave camp under the Khurdжин Pass, a camp on the Khurdжин Pass, and a "South" assault camp on the Yazglem-Dara Glacier under the southern slopes of Peak 26 Commissars, with necessary supplies and equipment.

On July 22, members of the assault team descended to the "South" camp to conduct a final reconnaissance and clarify route details. An initial attempt to ascend to the saddle southwest of Peak 5350 m revealed that the path was extremely hazardous due to a mobile icefall in the upper cirque of the glacier and avalanches blocking the route.

On July 23, the assault team climbed Peak Shipka via the western ridge to reconnoiter the path to the saddle from the east with the Revolyutsii Glacier and inspect the upper part of the route. However, thick cloud cover and subsequent bad weather prevented them from completing their task.

To finalize the ascent route, a reconnaissance trip was made on August 1 to the upper cirque of the Revolyutsii Glacier. The ascent path was chosen, and all parts of the route were inspected, with suitable bivouac sites identified.

4. Organizational and Tactical Plans for the Ascent

Climbing Peak 26 Baku Commissars from the south in such a remote area as the Yazglem-Dara Glacier cirque required clear organization. Analyzing our 1967 reconnaissance and financial capabilities, we concluded that, given our resources, the most feasible approach was from the north via the Khurdжин Pass.

A helicopter drop from Bartang would require about 20 hours, which was not feasible for us. The optimal solution was to drop cargo by helicopter onto the Abdukagor II pass (4 hours) followed by further transport. Our calculations proved correct, as even bad weather did not alter the plan.

By August 6, the day the assault was to begin, the "South" camp had:

- 120 kg of food;

- necessary supplies for the assault;

- equipment for the support group;

- rescue fund supplies.

Reconnaissance data showed that the route with an ascent to the saddle from the west was hazardous. Therefore, we modified the initial part of the route to ascend to the saddle from the southeast via the Revolyutsii Glacier.

We planned to complete the route in 7 days. During the ascent, the group had a 10-day supply of food and fuel.

From August 1, a CSKA team began working in the area, planning to traverse Peaks 26 Commissars and Revolyutsii. The departure dates of both groups nearly coincided. At their request and considering the situation, our team decided to let the more experienced CSKA collective go first, agreeing to maintain a two-day gap at the start of the route and adjust accordingly based on circumstances and safety conditions. Consequently, the assault start date was postponed to August 9.

During the assault, no changes were made to the route plan.

Only standard equipment was used during the ascent. Altitude measurements were taken using an aviation altimeter.

5. Assault Team

As per the application: Main composition:

- Andreev G.G. — captain

- D'yachenko N.N.

- Kholmanskykh G.N.

- Kuznetsov E.S.

- Spiridonov L.K.

- Korzunin D.K.

Reserve participants:

- Gusev B.N.

- Lobanov S.D.

- Kharchenko E.F.

There were no changes in the team composition before the assault.

6. Route Progression

(see profile sketch, photographs, and table). On August 8 at 11:00, the assault team departed from the "South" assault camp. They circled the rocky spur along its lateral side and then along the edge of the Yazglem-Dara Glacier, approaching the Revolyutsii Glacier. Initially, they ascended the right (orographic) lateral moraine into the upper cirque, then turned towards the central part of the glacier to avoid rockfall from the spur's walls, navigating through open and closed crevasses. They stopped for the night on the median moraine at 17:00. The night before the assault was tense due to continuous rockfall from the grand walls surrounding the cirque, creating a "rock sack."

Route

On August 9 at 3:30, we departed from the 4370 m camp. In complete darkness, using electric torches, we crossed the glacier and began ascending the avalanche cones through the bergschrund towards a broad rocky ridge. The snow crust with small calga-spores held firm. At 4:20, we reached the rocks. We moved simultaneously in teams, maintaining a high tempo to gain as much altitude as possible early on and avoid the rockfall zone. The ascent direction was towards the gorge between the rocky ridges where snow remained, allowing for high-speed movement. The rocks around were heavily scarred by rocks. The slope steepness increased, with frequent ice sections that sharply reduced our tempo (R0–R1). Thus, we adhered to the edge of the rocks where we could organize protection through ledges. Due to the gradually increasing layer of ice and rock steepness, we reached the rocky ridge by 7:40, especially as the sun had already illuminated the upper slopes.

The rocks in the lower and middle parts of the ridge (R1–R2) were monolithic and slab-like; we overcame them with free climbing (photo 3) and alternate belays. Around 10:00, rocks began to fly past us along the lateral snow and ice gullies. We ascended the ridge, moving from its left side to the right, heading towards the left (by direction) side of the hanging glacier. At 14:40, we stopped for the night as ascending to the hanging glacier in the second half of the day was dangerous. We bivouacked on a ledge under the cover of rocks. For the day, we had 2 hours of intense climbing. The weather was perfect, windless.

On August 10 at 5:00, with the dawn, we resumed our ascent along the ridge. The steepness and nature of the rocks changed (R2–R3); they became more weathered, with some snow and ice. The pace slowed. We used alternate belays, employed piton hooks, and cut steps. By 7:00, we reached a small ascent on the ridge covered with snow. Further along the ridge, we would have been directly under the hanging glacier's drops, so we transitioned to a shorter ridge on the right, which led to the safer central part of the glacier.

The traverse proceeded as follows:

- Initially, we traversed a couloir, setting up two rappel lines;

- Then we ascended directly up the central part of the ridge (R3–R4).

The rocks were weathered (photo 4), mostly wet, with some difficult and unpleasant sections.

As we ascended towards the hanging glacier, the rocks became increasingly snow-covered, with ice cornices or "sheep's backs" on the rocky ascents in multiple tiers. We either circumvented these or cut through them.

By 12:30, we reached the hanging glacier. Our ridge gradually turned into sheer and extremely weathered rocks, over which large cornices hung from the saddle. Therefore, from the rocks, we turned left into a broad ice gap along steep ice covered with a thin layer of snow.

The first team, wearing crampons and cutting steps, with five ice hooks, reached the lower part of the gap, setting up rappels (2 × 40 m) and receiving the rest of the participants.

Then:

- We moved up to the right,

- avoiding ice drops (photo 5),

- and ascended to the more gradual central part of the glacier.

At 15:00, we reached a snow saddle by wet and deep snow, where we set up both tents. For the day, we worked 10 hours in clear, warm weather.

On August 11 at 8:00, linked together, we began ascending in crampons along the snow and ice ridge (R4–R5). Under a thin layer of hard snow was ice. To the right were large cornices, and to the left, the slope dropped steeply to a plateau. As we ascended towards a rocky outcrop consisting of several fan-shaped ridges, the slope steepness increased.

For belaying:

- We hammered in three ice hooks;

- Sometimes we cut steps.

The ascent to the rocks was via an ice pitch using rappels (30 m). The further path lay across heavily weathered rocks (R5–R6) and along the boundary between rocks and ice — traversing upwards to the right. Belaying was only alternate, using pitons. In the middle section, the rocks were so weathered that they resembled damp clay with ice.

We moved cautiously and only along rappels (4 × 40 m), sometimes ascending rocks or descending to the edge of the precipice. The ascent to the ridge was via a rock wall (20 m) with many loose rocks and icicles. We had to knock down an ice cornice due to its unreliability. Only by 14:00 had the entire group passed this section.

Above the rocks, we continued our ascent along a broad snow and ice slope (R6–R7). The shallow (5–10 cm) wet snow offered no grip. We ascended slowly with belays through ice hooks (photo 6). It was very hot. By 18:00, we reached a rocky outcrop, where we organized a bivouac under its cover, leveling a good platform.

On August 12 at 6:00, from the bivouac, we immediately began ascending towards the "Tooth" pinnacle, hoping to quickly reach the ice funnel. However, the steep and hard ice required setting up rappels and reliable belays.

We ascended slightly to the left of the "Tooth" pinnacle, where the ice was even steeper; we followed the direction towards the middle of the ice knife descending from the pinnacle's summit. We moved along rappels on ice hooks, cutting basins for belay points. It took almost 3 hours to complete the section (R7–R8).

When the last participant reached the pinnacle's summit at 9:00, a rock shot past like a cannonball, splintering on impact. We quickly rappelled down 80 m of rope to a platform below, where, under the cover of the pinnacle, we were forced to organize a bivouac on a small, narrow platform laid out by the CSKA team. From 10:30 to 11:00, there was continuous rockfall around the pinnacle, with several strong rockfalls in the ice funnel.

The bivouac conditions were challenging:

- The platform was small, barely accommodating one tent;

- We slept on one tent, covered with another;

- The weather was fairly warm;

- The night was windless.

On August 13, waking up before dawn, at 3:30, we ascended to the pinnacle's summit via the prepared rappels and began climbing in crampons up the ice knife. We hammered in ice hooks for belaying and traversed the ice funnel to the right towards the rock wall on the opposite side.

(One of the assault options considered ascending the ice knife under the wall with a traverse of the funnel under the wall at the boundary between ice and rocks).

(As observed the previous day, the wall, consisting of three rock belts, had a negative slope on the upper rust-colored belt, with large icicles hanging from it, as seen in photo 9. All rocks and the base of the wall were covered with ice, making this path highly problematic and dangerous).

The funnel represented a large ice gully with steep (up to 60°) ice, narrowing downwards and intersected by several smaller gullies, with water flowing from above during the day.

Passing through the funnel:

- The first participant, without a backpack, in crampons, cutting steps, passed through the funnel and set up rappels (50 m);

- The others followed along the rappels on sliding carabiners with lateral belays using a 60-meter Reps cord;

- After passing the dangerous spot, we moved under the cover of rocks (photo 7).

By 8:30, after successfully passing the funnel, we all gathered on the rocks. It was very cold.

Further movement:

- Along an inclined shelf, we traversed to the right;

- Behind a small bend in the rocks;

- We ascended to the beginning of the light-yellow wall (R8–R9).

The light-yellow wall (40 m) was composed of what appeared to be large cubes (photo 8). The rocks were of medium difficulty, interspersed with difficult sections. They were heavily weathered. Belaying was with pitons. We moved cautiously to avoid dislodging large rocks onto our companions below.

From the wall, we reached a small ledge. From there, a section of black schist led upwards (about 15 m):

- It was not possible to organize piton belays due to the friable nature of the rocks;

- We proceeded with extreme caution.

Next, we ascended a wall of light marble (40 m):

- The rocks were difficult, forming large monolithic slabs;

- There were many loose rocks;

- There were few cracks for piton belays (photo);

- In the upper part of the wall, during ascent along a vaguely defined internal angle, we were thrown off the rock face.

We reached a small, sharp, nearly horizontal shoulder with depressions and rocky fingers.

By 15:00, we ascended to the foot of the next wall. Here, the CSKA team had bivouacked. We decided to set up a bivouac:

- Without wasting time and energy searching for and preparing a platform;

- We slightly expanded the previous one and squeezed in a second tent for two people.

Additional actions:

- We immediately began processing the wall;

- We set up 40 m of rappels.

The day's total:

- 12 hours of movement;

- Altitude: 5890 m according to the altimeter;

- The night was cold, with wind.

On August 14, 1969, at 9:30, after the sun had warmed the rocks, we began ascending the wall using the rappels set up the previous day (R9–R10):

- The rocks were monolithic, in the form of large cracked marble slabs;

- We ascended with backpacks (it was not possible to pull them up the wall without risking dropping rocks onto our companions below, who had no place to hide);

- Climbing was very difficult.

Overcoming the wall:

- We ascended along a narrow crevice (photo 9);

- After 30 m of overhanging rock, the wall transitioned into steep (up to 60–70°) slabs leading under нависающие скалы;

- Further ascent was along the slabs slightly to the right, bypassing the нависающие скалы;

- The slabs were made of black schist, heavily smoothed;

- There were few cracks, and the pitons we hammered in held poorly (photo 10).

From the slabs, we reached a narrow ledge. From there:

- We ascended upwards along an internal angle for 40 m (photo 11);

- The angle was formed by the layering of marble and black schist;

- The angle was sheer, with нависающие скалы on both sides;

- All holds were made of loose rocks;

- The pitons held unreliably;

- We hammered in two wedges and a drill piton.

By 15:00, we passed the wall and reached a clayey slope with fine scree at an angle of about 45°.

Further progress:

- After 30 m, we approached a triangular rock wall;

- To the left of it, rocks were falling down an ice gully;

- The path upwards was to the right along weathered rocks;

- We circumvented the wall and reached a sharp ridge;

- At the beginning of the ridge, there were snow cornices (R10–R11);

- We ascended along rappels (3 × 40 m) with belays through ledges;

- Through a small depression, we reached under the wall;

- We circumvented the wall to the left with short dashes, shielding ourselves from rocks in an internal angle;

- The angle (70°) led to the top of the wall (20 m);

- From there, we ascended upwards along inclined slabs of a rocky gully;

- We set up 50 m of rappels (steepness 55°).

By 18:30, the gully led us to the foot of the rust-colored wall, which shone like a mirror in the rays of the setting sun.

The CSKA bivouac:

- Was on a steep ledge, with a nearly meter-high stone wall;

- The platform was about 1 m wide;

- We processed the wall until dark;

- We bivouacked in a semi-reclined position;

- Altitude: 6080 m.

On August 15, we woke up early. We were to tackle one of the most critical sections of the route — the rust-colored wall. The wall was sheer. In its central part, to the left of us, the height difference was less, and the rocks were more pronounced, but rocks were falling from a couloir above. Directly above us were smooth, sheer faces. We planned our route further to the right, near the wall's bend, where a semblance of a ledge was visible (R11–R12).

It was cold, and our feet were freezing. At 8:30, we started up the wall using the set rappels. The first 20 m involved ascending to a talus ledge abutting a vertical scarp. We pulled our backpacks up from the bivouac site using ropes.

From the ledge, a vertical scarp with a large detached slab extended upwards (photo 12). Between the wall and the slab was a narrow crevice; the rocks were unreliable. The crevice ended in a wall. The first participant took about an hour to pass one rope length and then, with careful piton belays, reached an inclined ledge. The ledge traversed the wall diagonally towards its right bend, where it widened slightly. We pulled our backpacks up again using ropes, swinging them from the lower ledge to the wall. By 12:00, all participants had ascended to the ledge, from which we began ascending the wall again (photo 13).

The rocks were difficult throughout, with few holds. There were almost no cracks for pitons. We overcame the wall with free climbing and piton belays, hammering in two drill pitons for reliability. In the upper part, through a small negative section, we reached a sloping, inclined ledge filled with fine scree. Above, the rocks changed; steep and loose rocks made of sandstone and black schist overhung. Further ascent was into a couloir. Just below and to the right of us, behind a rocky finger, we spotted a laid-out platform. Descending to it by traversing, we found ourselves at the CSKA bivouac, where we retrieved a note left in the second control checkpoint. The time was 14:30.

We continued our ascent in the couloir along schist slabs. Unpleasant black boulders overhung the couloir. It was almost impossible to hammer in pitons as the rock flaked off. We passed the first rope length slowly and cautiously, waiting in shelter as participants descending the couloir dislodged rocks, despite taking precautions.

Gradually, the couloir turned into a wall, which, ascending to the right, led to the right side of the ridge thrust upwards (photo 14). Difficult and dangerous rocks led to a weathered crest. Belaying was with pitons and through ledges.

The path was blocked by a narrow, high, spade-shaped pinnacle. We traversed it to the right and upwards (40 m) along a loose wall, continuing into a small depression. From the depression, we ascended along a sharp, weathered, jagged crest (about 60 m), ending in a small ascent of about one rope length. The first participant advanced the full rope length with lower belay, as there were no ledges or cracks (photo 15). The rock was so weak that it crumbled into sand in our fingers. It was not climbing but literally "scratching." The last participant reached a small bend above this crest at 20:30. It was getting dark. We leveled one ledge on a protrusion and cut another into the ice, set up tents, and settled in for the night. We were tied to pitons hammered into the rocks 20 m above us. For the day, we worked 13 hours of heavy labor. This was perhaps the most challenging day of the assault. In the evening, on the pre-summit ridge, under the pinnacle, we saw the CSKA team's tent for the night.

On August 16 at 8:00, from the bivouac, we began ascending along slabs (one and a half rope lengths) under the base of a 60-meter bastion. The bastion transitioned with its right side into the southwest wall of the entire massif, and to its left was a snow and ice slope.

We ascended with belays through ice hooks under the bastion wall and then, bypassing it, along a steep (up to 55–60°) snow and ice slope for two rope lengths (R13–R14). Small calga-spores on the ice did not hold on the sun.

From the bastion's summit, we traversed about 20 m along a crumbly rocky ridge and then upwards to the right through a rocky wall (photo 16) with an ice cornice, reaching a short shoulder (about 10 m). In the middle of the shoulder was a sharp, needle-like pinnacle, with snow and ice cornices hanging on both sides.

In the first cornice, on the edge of the ridge, a platform was cut into the ice — here was the control checkpoint and bivouac of the CSKA team ahead of us.

The shoulder abutted a sheer, gloomy wall with several counterforts. Upon inspecting the wall, we did not find a feasible ascent route. The time was 12:30.

While organizing a temporary bivouac (photo 17), we set out to search for and process a further ascent route.

Descending from the bivouac, traversing the cornice to the right behind the next two counterforts did not yield anything promising. We had to start ascending directly from the saddle upwards into a semi-oval rocky gully, leading to a small ledge. There were no holds in the gully; the rocks were covered with what appeared to be scales, flaking off from below. A drill hook split the rock.

We found a way out by:

- Hammering in wedges and ice hooks from bottom to top;

- Setting up ladders (photo 18).

From the ledge upwards, beyond the wall's edge, a sheer, narrow rock chimney opened (R14–R15). Using spacers in the chimney, we ascended 40 m into a quartz vein, next to which was a crevice where one could stand by wedging oneself in.

Further:

- First upwards;

- Then over a bend in the wall;

- Traversing to the right;

- We moved onto inclined slabs (photo 19), from which the exit to the pre-summit snow ridge was visible.

The search for the route and its processing (setting up 120 m of ropes) took almost 5 hours of difficult climbing. During this time, our companions below on the shoulder cut out a platform on the edge of the cornice for a second tent. The bivouac was very comfortable. The altitude was 6630 m.

On August 17, using the set rappels, we began ascending with backpacks. It was not possible to pull the backpacks up on ropes, as large slabs could be dislodged from the upper middle part of the wall onto the bivouac site. Although the route was processed, ascending with backpacks was very challenging; we moved slowly. We reached the slabs by 11:00. From the slabs, across one rope length (photo 20), we exited onto the snow-covered pre-summit ridge.

Further, we moved:

- Simultaneously with alternate belays along rocky crests and snow and ice "ties" (4 × 40 m);

- We traversed a saddle in the ridge with large cornices;

- We began ascending along weathered rocks, traversing or circumventing snow and ice "ties" encountered on the way.

The weather began to deteriorate; fine graupel fell, and fog rolled in. Below, everything was shrouded in clouds. We traversed two sharp pinnacles to the right along weathered rocks and reached a snow slope. After three rope lengths on loose snow at a steepness of 45–50°, with alternate belays, we ascended to the summit ridge, which led us to the tour on the summit at 15:00.

The panorama of the surrounding mountains was obscured by clouds. It was snowing. From the tour, we retrieved a note left by the CSKA team, who had reached the summit a day earlier than us. We immediately began descending northward, taking advantage of brief clearances in the cloud gaps. We set up rappels and descended along rocks on the ridge leading to Peak Peredovoy. By 20:00, in snow and cold, we reached the ridge, where we organized a bivouac.

On August 18, from 9:00, we continued our descent along the ridge and by 18:00 reached Peak Peredovoy. The descent route followed a classified route of 5B category difficulty, so we omit the details of the route characteristics. By 19:00, we descended to the Fedchenko Glacier, where we were met by a support group, and by 24:00, we returned to the "North" assault camp, 10 days after leaving the "South" camp.

The ascent route is interesting and technically complex almost throughout its 2.5 km length. The group assesses the route as the highest category of difficulty.

7. Evaluation of the Assault Team Members' Actions

Movement on the route was conducted by three pairs. The team in this composition has been together for 5 years. Naturally, over this time, each member developed their specialization and role within the group. However, this did not preclude mutual substitution on the route.

Almost all participants had the opportunity to lead on the route. However, the most technically complex sections were led by the D'yachenko — Andreev team, with the Kholmanskykh — Kuznetsov team bringing up the rear. They carried the heaviest backpacks and were responsible for hammering in pitons, significantly determining the group's pace.

All participants fulfilled their duties.

The participants' well-being throughout the route was excellent, allowing the group to maintain a high ascent tempo at high altitude. This was the result not only of serious training in the preparatory period but also of nearly a month of acclimatization related to carrying cargo at altitudes above 5000 m.

The technical preparation of the participants met the route's requirements.

8. Support Groups

The large composition of the expedition — 22 people — was primarily due to the significant role assigned to the support groups. Conducting the expedition in an area with lengthy transitions and multi-day isolation of groups from each other required clear coordination. The solution was to equip the groups with radio stations. Four "Nedra-P" radio stations provided invaluable assistance in this regard.

During the assault, the entire expedition was divided into:

- 2 support groups;

- 2 notification groups.

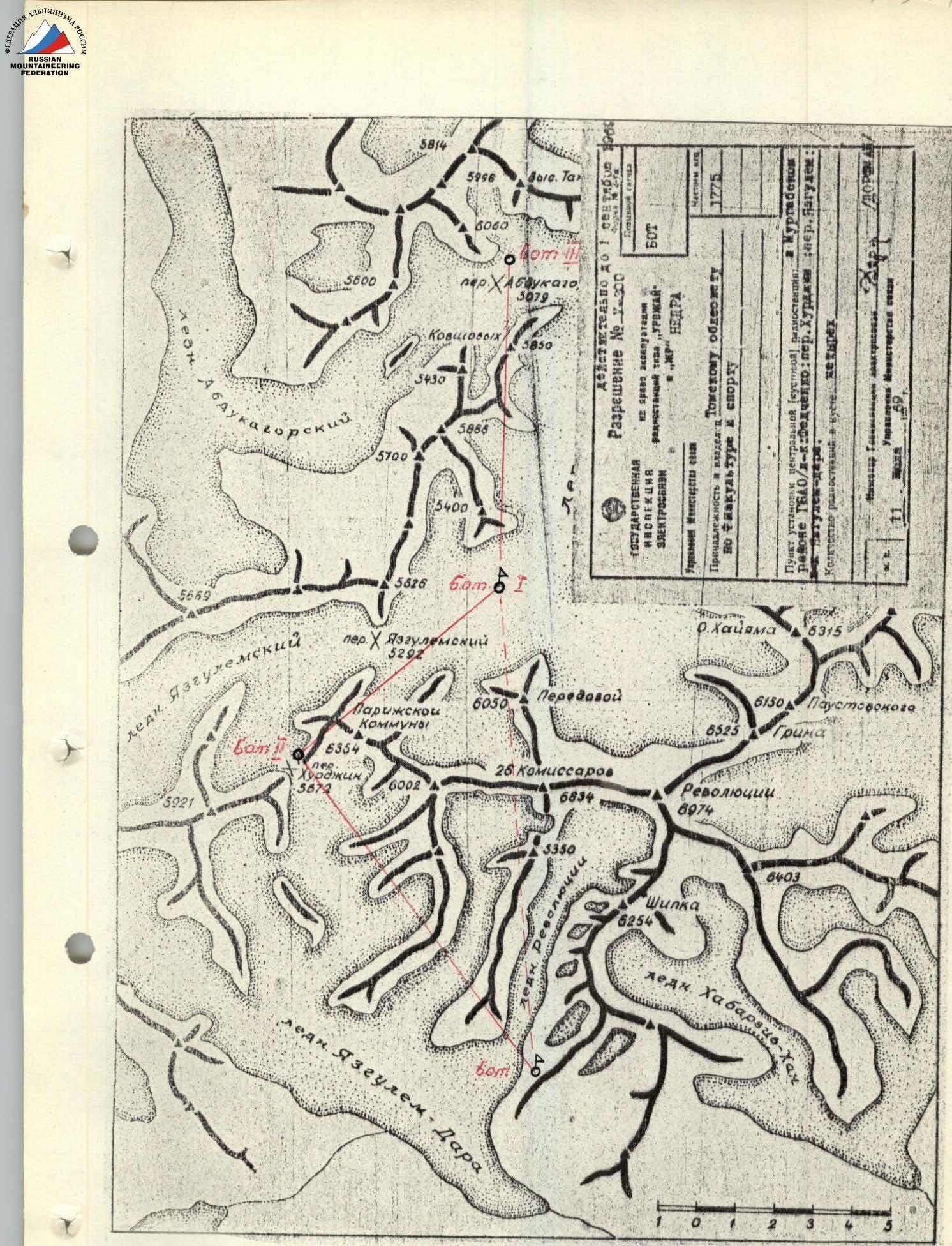

Fig. 2. Schematic of radio communication between support groups during the assault on Peak 26 Baku Commissars from the south.

1st support group:

- Lobanov S.D. — CMS, leader

- Gusev B.N. — CMS

- Slusarchuk V.F. — 1st sports category

- Zernov A.V. — 1st sports category

- Tarasov E.G. — doctor

1st notification group:

- Denisov V.P. — 1st sports category, leader

- Mashchenko V.N. — 2nd sports category

- Aksenov V.A. — 2nd sports category

2nd support group:

- Kharchenko E.F. — CMS, leader

- Molodezhnikov A.M. — 1st sports category

- Ovchinnikov A.N. — 1st sports category

- Avraamov S.D. — 1st sports category

- Tolmachev V.V. — 1st sports category

- Radionov N.A. — 2nd sports category

2nd notification group:

- Polishchuk Yu.G. — 2nd sports category

- Nikitin V.N. — 2nd sports category

All groups were equipped with radio stations, and each was assigned independent tasks.

The 1st support group, which also served as the observation group, was located in the "South" camp; the 2nd was in the "North" camp; the 1st notification group was on the Khurdжин Pass; and the 2nd was on the Abdukagor II pass. Communication between groups was maintained every even hour. The radio communication scheme in the area is presented in Fig. 2.

In the event of a distress signal from the route (1 red flare), the 1st support group would transform into the lead rescue team and move towards the assault group. The other groups, approaching via the Khurdжин Pass, would form the auxiliary rescue team. Overall leadership would be exercised by Lobanov S.D.

In the event of a distress signal from the upper part of the route and a call for the group from the north (2 red flares), the 2nd support group would take the role of the lead team, with overall leadership by Kharchenko E.F.

The 1st notification group acted as a liaison between the 1st and 2nd support groups; the 2nd notification group ensured the call for a helicopter from the 3rd section of the geological party, located near the base camp.

All groups successfully completed their tasks.

![img-2.jpeg]({"width