Climbing Passport

-

Climbing class — high-altitude.

-

Climbing area — North-Western Pamir.

-

Climbing route to the summit of Peak Kommunizma (7495 m above sea level) via the south-western wall.

-

Climbing characteristics: height difference — 2800 m; average steepness — 70°; length of complex section (90°) — 1540 m.

Number of pitons: rock — 501; ice — 15; bolted — 32.

-

Number of travel hours — 121.

Number of overnight stays — 23, half of them sitting.

-

Team of the Rostov Regional Committee for Physical Culture and Sports.

-

Team members: Anatoly Vladimirovich Nepomnyashchy MS — team leader, Alexander Nikolaevich Afanasiev — Master of Sports, Yuri Pavlovich Manshin — Master of Sports, Evgeny Pavlovich Khokhlov — Master of Sports, Valery Alekseevich Kolyshkin — Candidate Master of Sports, Konstantin Viktorovich Osipov — Candidate Master of Sports, Alexander Mikhailovich Shalagin — Candidate Master of Sports, Alexander Dmitrievich Tsymbal — Candidate Master of Sports,

-

Team coach — Anatoly Vladimirovich Nepomnyashchy.

-

Departure date to the route — July 23, 1977.

Return date — August 15, 1977.

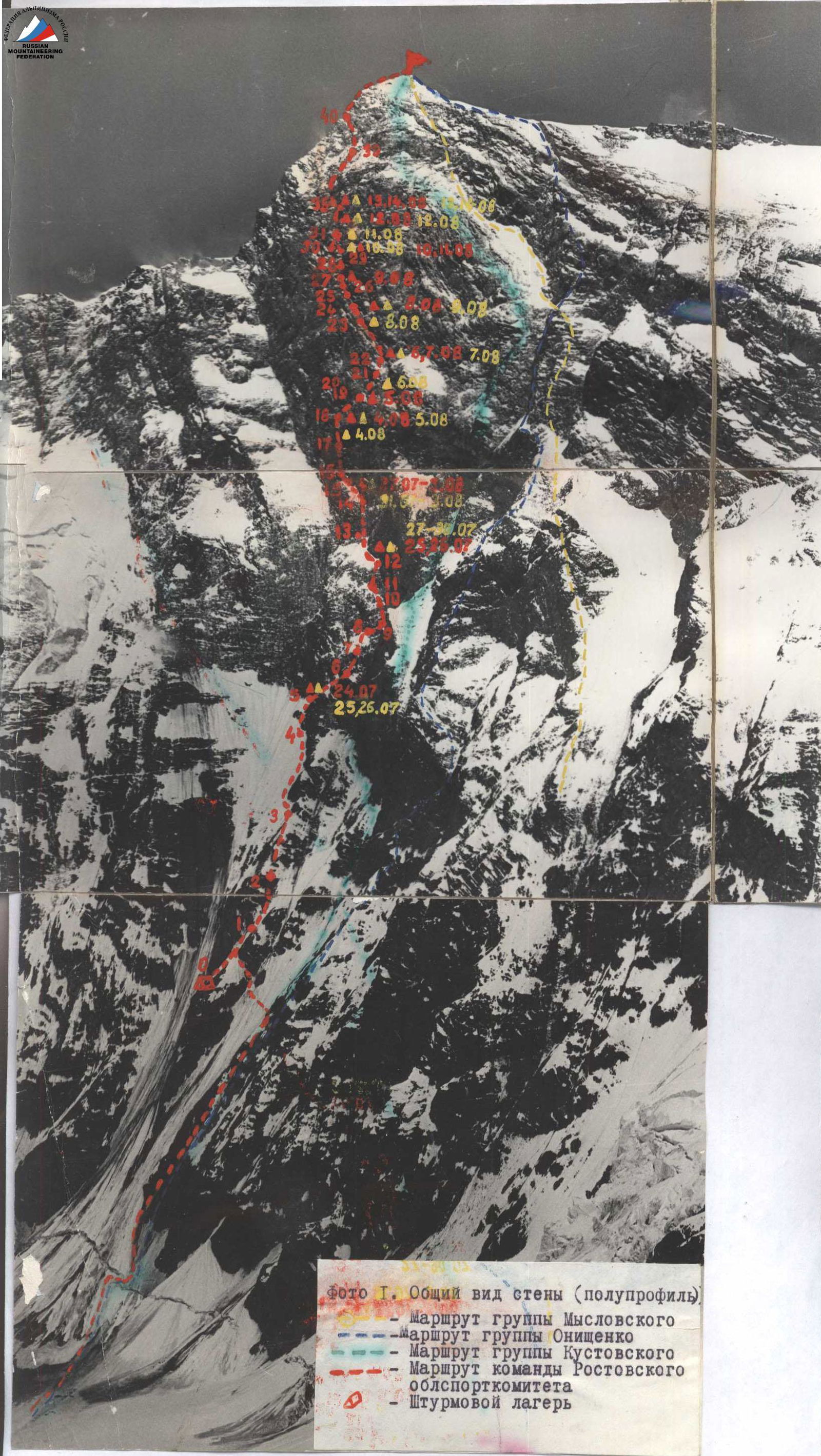

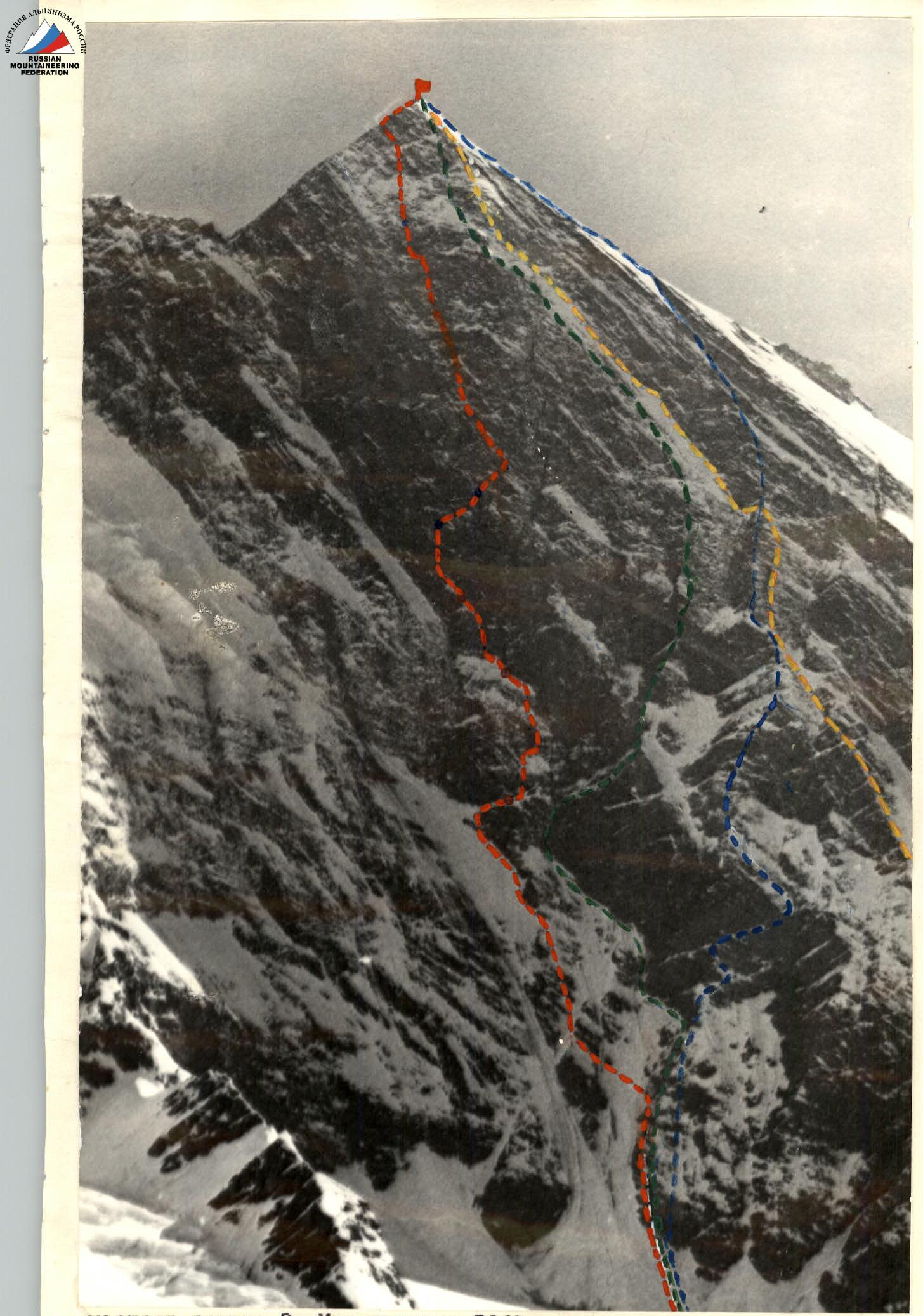

— route of E. Myslovsky's group in 1968 — route of V. Onishchenko's group in 1970 — route of A. Kustovsky's group in 1973 — route of the team of the Rostov Regional Committee for Physical Culture and Sports in 1977

I. Brief Geographical Description and Sporting Characteristics of the Climbing Object

Peak Kommunizma is located at the intersection of the Akademiya Nauk and Petr Pervogo ridges. To the north-east, the massif of the peak feeds the system of the powerful Bivachny Glacier — one of the tributaries of the giant valley glacier Fedchenko. A ridge descends from the peak to the north, reaching 7000 m, and then turns east.

To the north-west from the peak, at an altitude of 5700–6000 m, along the Petr Pervogo ridge, lies the Pamir Plateau. This is an almost flat firn field that drops off to the north with steep walls, at the foot of which the large Fortambek and Walter glaciers originate. The peaks of the Petr Pervogo ridge, limiting the plateau from the south, rise above it by no more than 800 m, but their even walls are quite extensive — about two kilometers, forming numerous cirques in the upper reaches of the Garmo Glacier. One of them gives rise to the Belyaev Glacier and is located at an altitude of 4500–5000 m at the foot of the south-western wall of Peak Kommunizma.

To the south-east from the peak, at an altitude of about 6000 m, lies the plateau of Peak Pravda, adjacent to the massif of Peak Kommunizma from the north, and dropping off to the west towards the Belyaev Glacier. From the eastern edge of this plateau, icefalls descend, feeding the system of the Bivachny Glacier. From the south, the plateau is closed by the massif of Peak Rossiya (see the map of the area).

Due to the high absolute altitude and exceptional diversity of laid and possible routes to the summit of the country's high-altitude pole — Peak Kommunizma (7495 m above sea level), as well as to the neighboring peaks of the Akademiya Nauk and Petr Pervogo ridges, this area of the North-Western Pamir is becoming increasingly popular among climbers of our country and foreign athletes year by year.

From 1933 to 1977, 17 routes of 5B and 6B difficulty categories were laid to the summit of Peak Kommunizma. It was not possible to find a simpler path.

Of these routes, seven start from the Belyaev Glacier, including those laid by the groups of E. Myslovsky, V. Onishchenko, and A. Kustovsky, which are considered, by general consensus, to be outstanding achievements of Soviet mountaineering.

These three routes of 6B difficulty category are laid along the north-western wall of the peak, which is considered by climbers to be the main attraction not only of the North-Western Pamir but also of the entire mountain system.

The peculiarity of the wall is that here:

- technical difficulties of passage are combined with the highest known location in the country;

- there is rockfall danger in the lower part.

The general view of the wall (semi-profile) is shown in photo 1, where the above-mentioned routes are marked:

- E. Myslovsky's group — with yellow dashes;

- V. Onishchenko — with blue dashes;

- A. Kustovsky — with green dashes.

These routes, accomplished in 1968, 1970, and 1973, respectively, наглядно illustrate the process of wall development and show the stages of approaching the solution of the main task — ascending the central part of the over-kilometer-high sheer wall, aptly named by climbers the "belly" due to the oval shape and some convexity of this part of the wall.

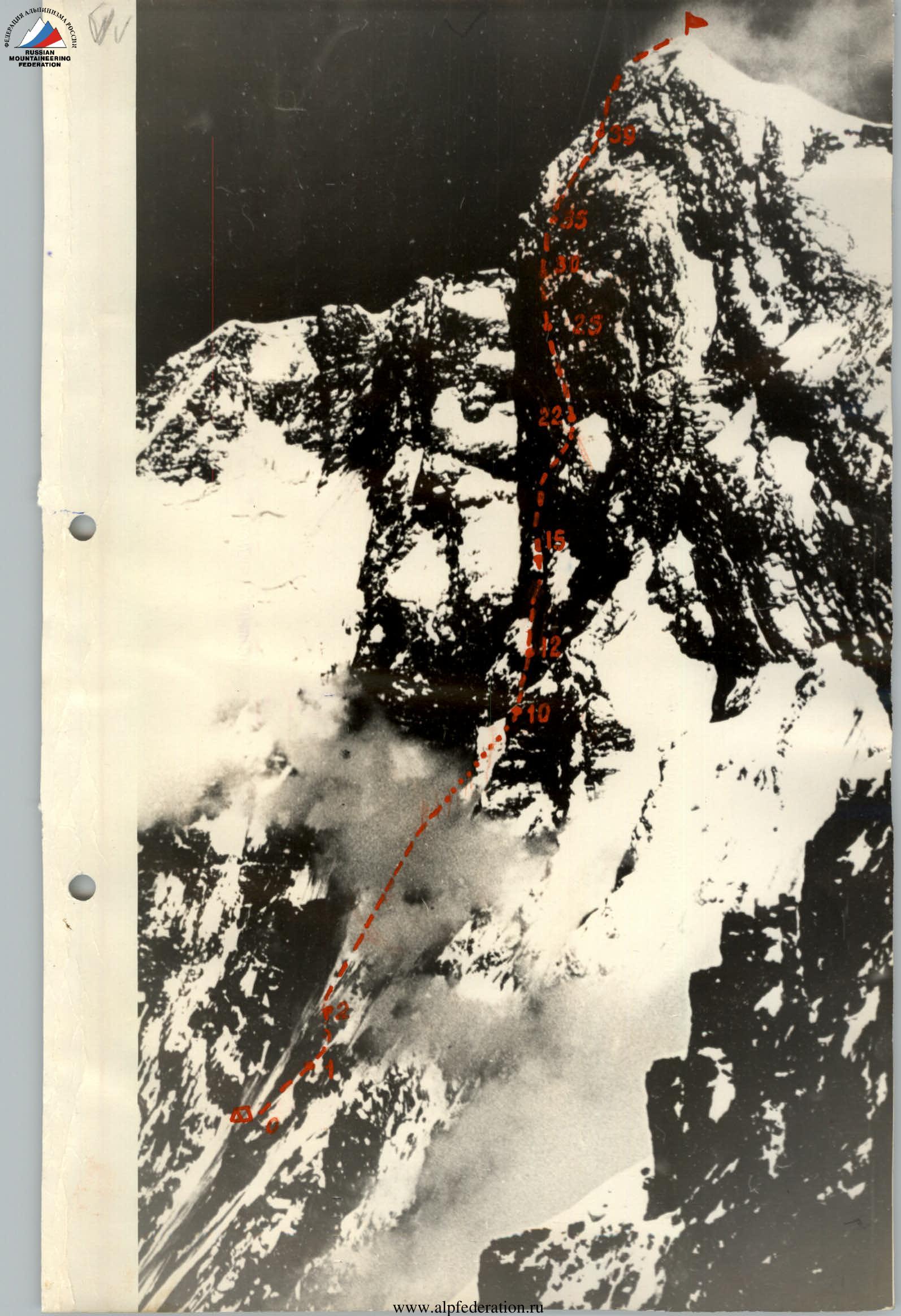

In photo 1, due to perspective distortions caused by the low location of the shooting point, the lower part of the wall seems to have a greater height difference than the upper part. In reality, the wall can be characterized by the following figures: the level of the foot — 4700 m; height difference of the lower part — 1200 m (up to 5900 m); height difference of the sheer part — 1250 m (up to 7150 m); height difference of the pre-summit slope — 345 m; average steepness of the lower part of the wall — 50–55° (see photo 2); average steepness of the upper part — 90°; average steepness of the pre-summit slope — 35–45°. On the left, the sheer part of the wall is bounded by large snow-covered surfaces of the Big Barrier slope, on the right — by snowy slopes and destroyed ridges, or rather counterforts, dissecting a large part of the north-western exposure of the peak.

The rocks composing the wall are highly diverse. The lower part of the wall consists of loose shale rocks and is therefore heavily destroyed. The lower part of the sheer wall, with a steepness slightly exceeding 90°, is composed mainly of monolithic rocks, but in some areas it is intersected by layers of shale rocks and a wide quartz belt. The upper part of the sheer wall cannot be subdivided into separate sections of noticeable size due to the exceptional heterogeneity of the constituent rocks.

The lower part of the wall, where the route of the Rostov Regional Sports Committee team is laid (red dashed line in photo 1), is a combination of rock and snow-ice surfaces, ridges, and couloirs, overall of the 5th difficulty category. The passage is complicated by rockfall danger. There are practically no safe places for organizing lying bivouacs in tents. An excellent place for a bivouac is the edge of a large ledge on the counterfort between two couloirs (location of the assault camp) at an altitude of about 5000 m. However, this place is located 100 meters away from the ascent route. There are places for safe sitting bivouacs.

The sheer part of the north-western wall has a very diverse relief, ranging from uncompromising monolithic walls to various ledges, cornice, internal corners, chimneys, and other elements of rock relief. An athlete of any high qualification will find a wide scope for creativity here.

There are rare rockfalls here, which are less dangerous due to the great steepness of the wall. In areas with large ledges, it is necessary to beware of ricochets.

2. Climbing Conditions in the Area

2.1. Exploration of the Area

The Belyaev Glacier area is considered to be well-studied by climbers. It is enough to say that only in the 1977 season, there were expeditions from Moscow, SAVO, Georgia, Sverdlovsk, and Rostov, and two groups of tourists worked here. Nevertheless, most of the walls surrounding the Belyaev Glacier are still waiting for their pioneers, as until now, most expeditions participating in the USSR championship have paid attention mainly to the most difficult walls of Peak Kommunizma and Rossiya.

2.2. Relief Features

Routes in the area under consideration are predominantly combined. Rock walls, as a rule, are destroyed, and therefore rockfalls are a common occurrence here. Due to significant glaciation and great steepness of the routes, avalanches and icefalls can be observed almost daily.

The Belyaev Glacier is the most dangerous to pass due to the large number of crevasses hidden under the snow.

In general, the main attraction of the area is the exceptional diversity of mountain relief. Here you can choose a purely ice, snow, rock, or combined route.

2.3. Weather Conditions

The climate of the Pamir is drier than in other mountainous regions of the country, due to which both snow melting and direct snow evaporation can be observed in sunny weather, when the level of solar radiation reaches 1.82 cal/(cm²·min).

In the Belyaev Glacier area in the 1977 season, frequent alternation of sunny days with bad weather caused by cold intrusions, carrying a large amount of moisture, was observed.

The southern wall of Peak Kommunizma has its own microclimate. Being a barrier to the prevailing winds from the Pamir Plateau, carrying moisture, the wall is often covered with clouds even when the weather is good in the area. At this time, heavy snowfalls are observed on the wall, causing a large number of powder avalanches and accompanied by a sharp drop in ambient temperature. During the two months of the Rostov Sports Committee expedition's stay on the Belyaev Glacier, there was not a single long period of stable weather on the wall. Usually, the wall could be observed for three days, then it was hidden in clouds, and after a few days, it appeared, dusted with fresh snow. In a couple of days, the snow flew off the wall, and then everything repeated from the beginning.

2.4. Remoteness from Settlements

Most expeditions usually organize their base camps in the Berezovaya Grove, near the tongue of the Garmo Glacier. There are two main routes to this place: through Tavil-Dara along the valleys of the Obi-Hingou and Garmo rivers, and from Jirgatal — by helicopters. Map 2 shows the route of the participants and cargo of the Rostov expedition. This path is the most convenient and fast with helicopter support. The nearest settlement to the Berezovaya Grove is Pashimgarm. However, despite the short distance (40–50 km), the path from this settlement to the Berezovaya Grove takes 2–3 days due to the frequent absence of bridges across the Kirgizob and other oncoming streams.

3. Reconnaissance Exits

After organizing the base camp at an altitude of about 4500 m, the team members made two reconnaissance exits under the wall to determine the future observation camp and the location for the assault camp. After completing a series of acclimatization ascents, on July 10, the observation camp was organized (see map 1), where at least four team members were constantly present until July 19, ensuring:

- constant observation of the wall,

- clarification of the paths and schedules of rockfalls,

- final determination of the route for passing the lower part.

4. Organization and Tactical Plan of the Ascent

Based on the study of reports on high-altitude ascents and consultations with leaders and participants of previous expeditions to the Belyaev Glacier, the following was established:

- The transition from the Garmo Glacier to the Belyaev Glacier and the approach to the wall is possible at any time during the sports season.

- For clear interaction with the rescue team, the base camp should be located as high as possible.

- The condition of the sheer part of the wall practically does not change during the season due to its great steepness.

- Rockfall danger in the lower part of the wall decreases during bad weather or immediately after it, during cloudiness and snow cover on the route. At the same time, as a result, the passage becomes more complicated.

- Previously passed routes required at least 15 days to complete.

- Movement along the lower part of the route is possible only until the sun's rays appear on the wall.

- Due to the strong frost on the wall (its sheer part) above 6000 m, effective work on the route is possible only after 12:00.

- The main reasons for unsuccessful attempts to ascend are: violation of the movement schedule on dangerous sections; shortcomings in equipment and gear; underestimation of secondary moments of organization and conduct of the ascent; and, as a result, injuries, illnesses, and moral unpreparedness. The large photographic material captured by the team allowed us to make the necessary conclusion about the nature of the relief of the south-western wall without conducting a reconnaissance expedition.

Since more than half of the team members did not have experience in climbing seven-thousanders, it was decided to conduct a lengthy acclimatization process. There was an opinion that such acclimatization would tire the participants and disrupt the main ascent. R. Parago, in his book "Makalu, Western Ridge," gave an exhaustive answer to this question — the conquerors of Makalu, moving up and down along the western ridge, practically made four ascents to seven-thousanders, spending about 50 days at an altitude of more than 6000 m above sea level without descending. This is also an answer to the opinion of some specialists that after 20 days of our stay on the wall, we should have had irreversible mental shifts. If this statement were true, the path to eight-thousanders for humans would be closed.

Taking into account all the above, the organizing committee of the expedition was engaged in preparation, the main tasks of which were: production of new down equipment, allowing work at altitude at extreme temperatures down to –40 °C; acquisition of high-quality high-altitude footwear; production of high-quality food products for the assault group and auxiliary personnel; preparation of a first-aid kit for the assault group; organization of a comfortable base camp, and many other things. By the end of May 1977, the main preparation was completed with the help of many enterprises in the Rostov region and thanks to the great desire of the team members to conduct the expedition at a high level.

After the expedition arrived at the Belyaev Glacier, organized the base camp, and completed acclimatization ascents, the following tactical plan for the ascent was developed:

- It was decided not to start the ascent from the observation camp, but from a specially organized assault camp, located 300 m higher, on a large ledge (see photos 1 and 2). The path to the assault camp is simple but dangerous. Movement along this path by the entire group with heavy backpacks would sharply increase the probability of injury. It was decided to organize the assault camp gradually, along with observation, by forces of one or two rope teams with light backpacks, ensuring good mobility.

- On the lower part of the route, it was planned to move in two groups of four with a one-day interval to ensure the possibility of a daytime transition from one safe bivouac site to another and for overall safety of movement along the destroyed rocks.

- The task of the first group of four on the lower part of the route was to quickly pass the route to the "airplane" — a characteristic snow-ice slope located at an altitude of 5800–5900 m, and to hang ropes on the rockfall-dangerous sections of the route to speed up their passage during cargo transportation from the assault camp, which was the task of the second group of four.

- Knowing that passing this route would require very great efforts from the participants, it was decided to pass half of the lower hanging part of the "belly" without removing the bivouac from the "bird" — a steep snow-ice slope located 100–150 m above the "airplane". At the same time, participants free from work were to finish transferring cargo from the assault camp to the "airplane" and further to the "bird".

- After removing the bivouac from the "bird", it was planned to move the entire group upwards simultaneously, for which each (except for the first rope team) was to move along the sheer wall with their backpack, using the "Yosemite" method (see "Description of Route Passage"), and excess cargo was transported by the usual method in special bags of streamlined shape.

- Taking into account the experience of groups that had laid routes to the side of the "belly", it was planned to take 18 days to complete the route and a week for bad weather. Based on this calculation, 97 kg of food, 12 liters of gasoline, and 8 gas canisters were taken for the front-runners.

- The planned 18 days for the route were distributed as follows: 3 days for the first group of four to pass the lower part of the route and 15 days for the sheer part, based on an average speed of 100 m per day. Of course, we knew that on the hanging part of the route we would not be able to develop such speed, but we hoped to make up for lost time after passing it. The ascent was carried out in full accordance with the specified tactical plan.

4.2. Equipment of the Assault Group

| Equipment, clothing, footwear | Quantity | Used on sections № | Total weight |

|---|---|---|---|

| Domestic main rope 10 mm | 800 m | R1–R22 | 65 kg |

| Imported main rope 12 mm | 240 m | R12–R41 | 20 kg |

| Duma-type climbing ascenders | 8 pairs | R1–R12 as climbing ascender and R14–R38 for lifting | 2.6 kg |

| Titanium carabiners | 10 pcs. | for ladders | 0.7 kg |

| Imported aluminum carabiners | 60 pcs. | everywhere | 4.5 kg |

| VISTI aluminum carabiners | 20 pcs. | -" | 1.8 kg |

| Extractor | 2 pcs. | everywhere | 390 g |

| Bolted pitons 8 mm | 60 pcs. | for ITO | 100 g |

| VCSPC drill | 10 pcs. | -" | 1 kg |

| закладные элементы модели В.М. Абалакова | 25 pcs. | everywhere | 1.2 kg |

| Petal rock pitons | 10 pcs. | R17, R18, R21, R38 | 0.1 kg |

| Blade rock pitons | 130 pcs. | everywhere | 4 kg |

| Box rock pitons | 60 pcs. | everywhere | 3 kg |

| Tubular ice pitons | 5 pcs. | R1, R3, R6, R8 | 0.1 kg |

| "Combi" ice-rock hammers | 3 pcs. | everywhere | 2.4 kg |

| Rock hammers | 2 pcs. | everywhere | 1.2 kg |

| Hammocks | 4 pcs. | on sitting bivouacs | 0.8 kg |

| Ladders | 12 pcs. | for ITO | 1.8 kg |

| Block-pulley | 2 pcs. | R17, R18, R20, R21 | 0.16 kg |

| Crampons | 8 pairs | R1–R4, R6, R8, R9–R12, R13, R15, R30, R40 | 8 kg |

In this section, we will briefly dwell on some features of the ascent that were not reflected in the table of main route characteristics.

On July 23, the first group of four, consisting of A. Nepomnyashchy, A. Tsymbal, E. Khokhlov, and K. Osipov, left the base camp at 4:00 AM and reached the observation camp in an hour with light backpacks. After a short rest, they continued upwards to the assault camp. We move without stretching, as the rocky slope starting after the bergschrund is heavily destroyed, and the rope can knock down stones on the lower ones. Actually, if it weren't for the rapidly increasing distance to the foot of the mountain, it would be better to go without ropes here, but as they say, insurance is needed where there is somewhere to fall.

After 2 hours and 30 minutes, we arrive at the assault camp. It's an excellent place for a bivouac, but we start loading our backpacks.

The initial total weight of equipment and food for the team was about 360 kg. Of this amount, approximately 70 kg was team equipment, i.e., footwear, clothing, and other items that each team member immediately put on or wore. To carry less, we were already going from the assault camp on a double rope, thus reducing the weight of the cargo by another 25–30 kg. Still, there were 260 kg left, or 32–33 kg per person. Moving with such backpacks on the lower part of the route was very risky — with such a load on your back, you can't jump aside or move quickly if necessary, so the second group of four had to make this journey twice.

We took a week's worth of food supplies, special equipment, and almost all the domestic rope for ropes. The backpacks were more than impressive, but the main load — the ropes — quickly "melted" as we moved upwards, and with each rope passed, we gradually accelerated our movement. That day, we gained about 1 km in height (counting from the base camp), but everyone's condition was good. At 11:00 AM, we stopped under a cornice at the beginning of an oblique shelf when the first sun rays illuminated the wall.

Further, there was a simple path, but individual stones began to fall from the wall, and we decided to try to make a bivouac at this place. The ice layer turned out to be shallow, and the hacked-out ledge was too small even for a sitting bivouac.

E. Khokhlov finds a solution:

- below the ledge, a hammock is stretched.

- We fill it with ice and snow.

- By evening, everything freezes, and a wide ledge for a sitting bivouac is formed.

The morning of July 24, 1977, promises bad weather. We think for a long time — should we remove the bivouac or not? Will we make it to the "airplane"?

The decision is simple:

- the high-altitude tent remains,

- and we leave with a light tent made of calendered nylon.

Section R6 — an inclined shelf (see route panorama and profile scheme) is not steep in itself, but is located on a steep wall, which is reflected in the profile scheme of the route combined with the panorama.

From section R7, our difficulties begin. Due to the ice forming on the rocks, we have to climb in crampons. Our "Nanga Parbat" type ice axes and special ice hammers greatly speed up our movement. By noon, bad weather catches up with us. Approaching section R12 — the last obstacle before the "airplane" — we descend, hoping that the snowfall will end tomorrow. We envy the second group of four. The guys were walking from the base with the remaining cargo and therefore spend the night in the assault camp in a well-established tent.

In the morning, there are no hopes for the weather. We wait until noon. The second group of four approaches, and we need to vacate the bivouac site. We decide to try to pass the last 70 m to the "airplane" in snowfall conditions.

With light backpacks, we quickly reach the base of section R12 along the ropes. Here we pick up our cargo, and the first rope team begins to pass the wall. The relief helps. Half of the section is a chimney filled with ice. Crampons and hammers help again. We emerge onto the "airplane" and see a group of Muscovites in a break in the clouds. They are setting up a bivouac a little below us — on a rocky triangle, where one of the overnight stays of A. Kustovsky's group was.

Our concerns are confirmed. The "airplane" plane is too steep, and under a thin layer of snow and ice, rocks begin. We manage to hack out two tiny ledges, on which a group of four can fit — two people each. We hang tents on pitons and start fighting the snow that accumulates between the tent and the wall and displaces us from the ledges. The night passes almost without sleep.

July 26. A snowstorm and frost force us to sit in tents. To avoid frostbite, we decide not to risk it and wait out the bad weather. We find a way to fight the snow by freezing the tents to the wall. Now it slides along the tent slope, and we can rest.

July 27. From the very morning, it's unexpectedly clear, and quickly passing along the "airplane", we start making our way to the "bird". It takes us almost 6 hours. Only 90 m, but the section is very steep, destroyed, and icy, and we are pleased with this day. Our place on the "airplane" is taken by the second group of four.

The next three days — again inaction. On the third day of bad weather, our mood starts to deteriorate, but towards evening, gaps appear in the clouds, and with them, hopes for better.

The next four days, the group works together, processing the hanging part of the wall. The rope teams working ahead change every day, the rest finish transporting cargo to the "bird". At the same time, the second rope team in the first group of four transports cargo from the "bird" upwards.

At the end of this work, we started to be bothered by rockfalls. We understood the artificial nature of their origin when A. Tsymbal, working ahead, barely dodged a falling bundle of pitons and carabiners. The cornice belt was passed, and the risk of injury from stones increased. Movement slowed down.

The message received via communication that the Muscovites had left their route and were above us was extremely unexpected. We didn't want to believe that for the sake of "sports interest", one could drop stones on each other's heads; after all, it was clear to everyone that moving along this often very destroyed wall without causing rockfalls was simply impossible.

It was decided to stop further processing and, being under the cover of cornices, to transfer the bivouac from the "bird" to the end of the processed section. We devoted August 4 to this.

By the end of the day, bad weather began. Having reached the end of the processed section, we again fell under fire and, taking cover wherever we could, waited for a lull. In the evening, we were forced to set up a bivouac. As a result, two people received severe bruises from stones. At 20:30, everyone heard a noise characteristic of a large falling object, and a moment later, it became clear to everyone — a person had died. In those minutes and hours, everyone wanted one thing — to turn back time and do everything differently, but all we could do was move, up or down.

The next morning, the calm voice of the head of the rescue expedition, Fedorov, brought us back to reality. The ascent was continued. Continuing bad weather and relief complexities required maximum attention. In addition, it was necessary to urgently find a convenient place for a bivouac and get a good night's sleep at least once. On August 6, the first group of four reached such a place but did not have time to make a comfortable platform. On August 7, we did not risk leaving this place and, having processed part of section R23, slept well in two tents on a snow overhang, somewhat off the route.

On August 8, we approached the end of section R23 — an inclined shelf made of slabs.

Before us again was a wall in the full sense of the word, but not at all like the lower part. From the base camp, it seemed that this part of the wall was much simpler than the lower part due to the large number of large and small snow-covered ledges. Upon closer acquaintance, the ledges turned out not to be ledges, but steep sections of rocks under cornices and small cornices, plastered with snow — a phenomenon familiar to us from Peak Engel'sa. There were, of course, ledges and outcroppings where one could catch one's breath, but we could stand on our feet properly only on the "roof".

The passage of the upper part of the sheer wall was without any surprises or incidents. The main difficulty lay in working on the sheer wall in conditions:

- extremely low air temperature,

- strong wind,

- lack of oxygen.

The procedure for exiting the route usually took about 2 hours. Of these:

- 1 hour — getting dressed, putting on boots, and packing a backpack,

- 15–20 minutes — breakfast,

- about 40 minutes — bringing hands and feet back to life after leaving the tent.

As soon as a person left the tent, they immediately fell under the power of cold and wind. To move, it was necessary to remove at least one pair of mittens, after which the hands instantly froze. It was possible to restore blood circulation and warm up the hands only after intense gymnastics (swinging movements, rubbing, clapping, etc.). Finally, the hands were ready to work, but during this time, due to standing still, often in a very uncomfortable position, the feet began to freeze, despite double boots and 2–3 pairs of socks. It was necessary to repeat everything from the beginning, but this time for the feet.

It turned out to be a forced morning gymnastics, or rather, mid-day gymnastics, after which, along with the arrival of warmth, lethargy disappeared, and a desire to move forward appeared. As a rule, on the first few meters, everything was forgotten — the cold, the wind, the snow — there was only one thing left: without stopping for a second, to reach the place where the next piton was to be hammered in, to secure oneself, and, sitting in a harness, to bring breathing and numb hands back to normal. Then — an accurate calculation of the next segment and another dash…

On this part of the route, mistakes were made. The false ledges, which from below seemed to be a panacea, were misleading. After reaching such a ledge, it suddenly turned out that it was possible to stay on it only by continuously moving. Here, reserves of human strength were used, which are spoken of as a blank spot in human psychology and will.

The last seven days spent on the route did not spoil us with good weather. Two-thirds of this time was spent moving in fog or snowfall conditions. The situation became complicated when we rose above the Big Barrier. All winds from the Pamir Plateau were at our disposal until the very summit and even on the first stages of descent. Out of 3.5 days of descent, 1.5 days were also stormy, but here we were already walking, and heavy snowfalls and fog could not overshadow the joy of victory.

Note: To avoid cluttering the report with unnecessary repetitions, the authors made this section quite brief, considering that all the main moments of the ascent are reflected in the protocol of the ascent analysis and the table of main route characteristics. The nature of the relief is shown on the below-given panorama of the route and several photographs of characteristic sections.

TABLE OF MAIN CHARACTERISTICS OF THE ASCENT ROUTE Peak Kommunizma via the south-western wall. Summit height — 7495 m above sea level. Height difference of the route 2800 m, including the height difference of the wall section of the route with an average steepness of about 90° — 1250 m, starting from 5900 m to 7150 m. Route length — about 4200 m (from the assault camp and about 4800 m from the foot of the mountain). Length of sections on the wall part of the route — 1540 m. Pitons hammered: rock — 501 (1/3 закладные элементы); bolted — 32; ice — 15. Number of days on the route — 23.5, of which working days — 18. Number of travel hours — 121.

| DATE | Section | Average steepness in degrees | Length in meters | Relief character | Difficulty | State | Weather conditions | Rock | Ice | Bolted | Rock | Ice | Bolted | Exit from bivouac | Stop on bivouac | Number of travel hours per day | Bivouac conditions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| July 23 | R1 | 40 | 50 | Snow-ice couloir | 3 | good | 2 | 2 | on crampons | 7:30 | First group of four. On the inclined shelf of section R6. Second group of four in base. | ||||||

| R2 | 40 | 130 | Rocky slope | 4 | destroyed | -" | 2 | free climbing | |||||||||

| R3 | 30 | 160 | Implicitly expressed rocky ridge turning into ice | -" | 6 | 3 | |||||||||||

| R4 | 45 | 300 | Snow-ice slope | -" | 15 | ||||||||||||

| R5 | 50 | 70 | Rocky slope | 4 | snow-covered on top, icy in places | -" | 8 | 11:09 | 3.5 | Sitting bivouac in a tent suspended on pitons and supported from below by a hammock. | |||||||

| July 24 | R6 | 30 | 140 | Inclined shelf | 3 | snow-ice | cloudiness | 7 | 3 | 7:00 | |||||||

| R7 | 70 | 60 | Rocky wall | 1 | destroyed, icy | -" | 10 | ||||||||||

| R8 | 60 | 90 | Snow-ice slope | 1 | -" | 7 | |||||||||||

| R9 | 20 | 40 | Inclined shelf | 4 | snow-covered | -" | 7 | ||||||||||