«Kirpich»

(Classified as 5B+1 cat. Protocol №187 from 27.10.1961)

Via South Face

Combined team of Central Council of the Voluntary Sports Society “Trud”

Coach Honored Master of Sports of the USSR — G.P. Kolenov, Team Leader Honored Master of Sports of the USSR — Yu.I. Chernosliven

Tourist Club, reading room 2764 Moscow, 1960

Tourist Club, reading room 276A

HUMAN PERSISTENCE. A person's desire to shave off a tenth of a second from a record, to take away another centimeter from an unconquered height, to do what seems to be beyond human strength, to assert truly limitless human possibilities and make others believe in them - isn't this the calling of any sport!

The first steps of our technically complex mountaineering were timid. It took many years for the walls we traverse to reach the level of world-class walls. Only a few of our traversed walls can be named alongside the famous routes of Eiger, Petit Dru, etc. But ascents similar to those that have become classics, via technically complex paths to the summits - Grand Capucin, Lavaredo, and several others - have not been made in our Union.

The walls of Uchon and Chatyna were just the first steps. We needed to find a wall route that could be rightfully called a wall.

Brief geographical, geological, and sports characteristics of the Gvandra region

Reading the book by Academician Delone "Peaks and Passes of the Western Caucasus," we came across the author's words: "... to the south, Kirpich drops off with a sheer thousand-meter wall..." This caught our attention, and we decided to familiarize ourselves with the Gvandra region in more detail. A relatively small region of the Western Caucasus, located in the upper reaches of the Morda, Kichkinokol, and Uzunkol rivers, first attracted the attention of mountaineers in the mid-1930s. A relatively mild climate, stable weather, and convenient approaches - all this quickly earned the region popularity.

But after the war, the region was abandoned, and it wasn't until 1960 that an alpine camp was re-established here.

The mountaineering history of the region is associated with ascents to the peaks Dalar, Gvandra, Filtr, Dolomiti, and Dvoinyashka. A group of Leningrad mountaineer-physicists, who were among the first to make ascents to the region's peaks, were generous with "physico-technical" names for the peaks. But perhaps the most successful was the name given to an unnamed peak on the Main Caucasian Range with a height of 3800 m, which, along with Dalar, Dvoinyashka, and Zamok, can be attributed to a single geological group of peaks in this region. The peak was named "Kirpich." The first ascent to this peak was made only in 1960 by a group of climbers led by Varfolomeev.

The simplest paths of the first and third categories of difficulty run along the northern slopes of the peak, which are washed by the Morda glacier.

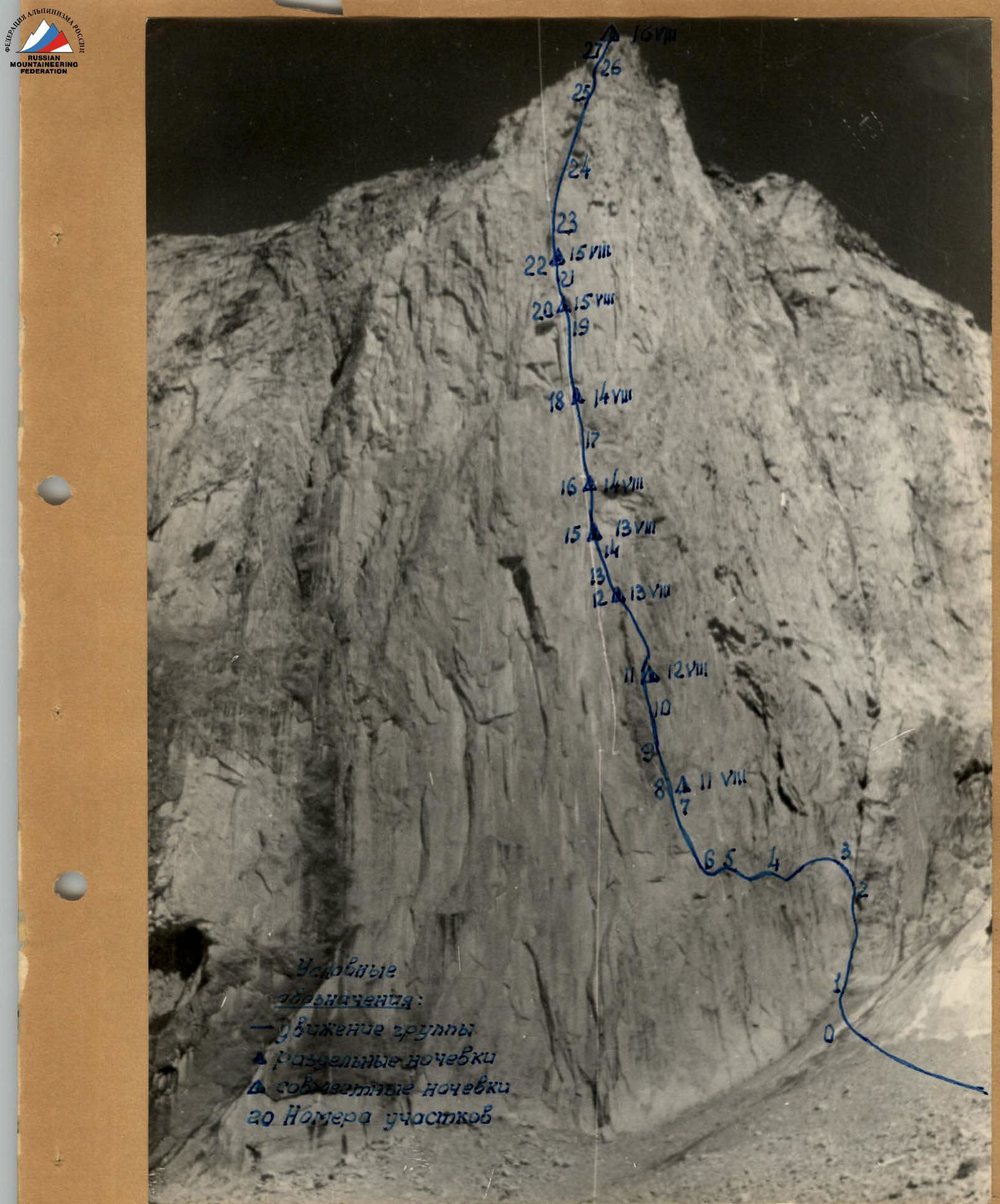

The southern slope, which drops off with a hundred-meter wall, is washed by the Dalar glacier, on which the base camp was set up.

The south face of "Kirpich" can be fully classified as a wall of the so-called pure type; slopes of great steepness without pronounced ridges, couloirs, or other macro-relief. The path up such a wall can be taken 5 meters to the left or 10 meters to the right with equal success, without giving the climber a significant advantage.

The features of the geological structure of the massif to which "Kirpich" belongs determine the characteristic fault forms of the peaks in this massif.

Large intrusions of basic and then acidic magma that emerged in the late Lower Paleozoic, and the folding that occurred in subsequent periods, served as the basis for further mountain formation. Belonging to the Alpine geosynclinal belt of the Greater Caucasus, the "Kirpich" massif is an anticlinorium of northwest strike.

The uplift of the Greater Caucasus became particularly intense in the Quaternary period, as the Caucasus turned into a high-mountain country.

The emergence of the "Kirpich" massif is most likely the result of magma loading in the thickness of deep-seated crystalline rocks that form the foundation of the ridge.

The peak is composed primarily of gray and, in its middle part, pink fine-grained granites with characteristic shallow cracks in which pitons hold very poorly.

This factor determined the characteristic large-block structure of the rocks that make up the massif.

The summit part of "Kirpich," composed of relatively soft rocks, has been more significantly destroyed. But overall, "Kirpich" is a strong, relatively little-destroyed peak, unlike many others in this region.

Composition of the sports team

The main composition of our team consists of instructors from the "Ullu-Tau" alpine camp.

Before the ascent, a reserve climber, 1st category Potapov A.N., was included in the main team. The decision was communicated to the representative of the USSR Alpine Federation, Zak P.S., and sanction was obtained for his inclusion.

The group participating in the assault operated in the following composition:

Assault group

- Chernosliven Yu.I. — leader

- Nikolaev Yu.N. — participant

- Senachev G.M. — participant

- Potapov A.N. — participant

Support group

- Kosobokov L.I. — leader

- Razzhivin A.I. — participant

- Isaev Yu.I. — participant

- Popov L.G. — participant

Throughout the assault on the "Kirpich" peak, the support group remained at the Base Camp on the Dalar glacier, maintaining visual and audible contact with the assault group.

Detailed data on the groups are provided in tables №1 and №2.

| Surname, first name, patronymic | Year of birth | Category | Alpine experience | Party affiliation | Main profession | Number of ascents cat. difficulty | Training | Nationality | Home address |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chernosliven Yuri Ivanovich | 1927 | Master of Sports | 1947 | non-party | electrician | 10 | skiing | Russian | Leningrad, Engels Prospect, 21, apt. 126 |

| Nikolaev Yuri Nikolaevich | 1931 | Master of Sports | 1950 | non-party | technician-technologist | 8 | skiing, athletics, hockey | Russian | Moscow I-411, Krestovsky Lane, 13, apt. 6 |

| Senachev Gennadi Mikhailovich | 1926 | Master of Sports | 1951 | non-party | turner | 9 | skiing | Russian | Berezniki, Demenev St., 11, apt. 16 |

| Potapov Alexander Nikolaevich | 1935 | 1st category | 1955 | non-party | engraver | 3 | skiing, basketball | Russian | Leningradskoe shosse, Revolutsii St., 126, apt. 14 |

Assault

August 2

At 8:00, we leave the bivouac. Here is the wall. From here, it doesn't seem so imposing. We feel a slight excitement. How will the ascent turn out? After checking once again that we have all the necessary gear and that it's properly distributed, the first rope team (Chernosliven – Nikolaev) sets out onto the rocks. At a fairly quick pace, we traverse a chimney and climb up difficult rocks to an inclined ledge about 40 m long. At the end of the ledge, there's a rock outcropping. After the outcropping, we descend to a wider ledge via inclined ledges to receive the backpacks. Time is 10:00. Until 11:15, we haul up the backpacks. Then the second rope team catches up with the first. Breakfast. At 13:30, we resume our ascent.

Via rocks of medium difficulty (such as outer and inner corners), we approach the wall. Traversing the wall, we come to a vertical inner corner where the first climber has to use a belay stance. From the inner corner, we emerge onto a fairly comfortable ledge about 1 m wide.

It starts to get dark. We hurry to haul up the backpacks. At 19:50, the whole group is together. Using flashlights, we settle in for the night.

August 12

After a strenuous day, we sleep until 7:00. The first rope team starts work only at 8:40. Nikolaev, who tried to speed up the ascent on the first day by not using a belay stance, now has to use it on the first few meters of the route. The wall is almost sheer.

A negative inner corner offers no footholds. It's hard to find places to hammer in pitons. Unnoticed, evening arrives. It's time to stop for the night.

Finally, we emerge onto an inclined ledge 0.6 m wide and 2 m long. Above and to the right, there's another ledge, 0.4 by 1.3 m.

Each of us chooses a spot for the night. Nikolaev prefers to spend the night on a belay stance.

August 13

Gradually, the rising sun starts to warm us. As quickly as possible, we pack up on the narrow ledges, and at 7:10, we're on our way. The "road" goes up and to the right via difficult block-like rocks, then traverses left to a platform 0.4 by 0.8 m. From the platform, there's an outcropping upwards, followed by a completely smooth wall. The main stage of piton work begins. The weather remains consistently "good." The sun beats down on our backs and heats up the rocks. Salty sweat stings our eyes, and the celluloid visor doesn't protect us from the dust kicked up by the piton hammer.

But finally, the sun sets behind the ridges, and it immediately becomes cool. We stop for a bivouac. The second rope team is 35 m below the first. We've hauled up 2 ladders, each 16 m long. To one of them, we've attached two short ladders. The first rope team hauls up 4 backpacks and then sets up a night's rest on artificial platforms. Senachev settles in on a rock platform 0.4 by 0.8 m. Potapov spends the night almost standing, in a rock outcropping. The hours of the night drag on, seemingly endless.

August 14

August 14, 6:00 — wake-up. Our feet ache from the hard platforms, and our toes are swollen from handling the ropes, especially when hauling up backpacks. They won't bend, and we have to massage them for a long time. At 7:45, the first rope team starts moving and, leaving a cornice to the right, emerges onto slanting footholds. Hauling up backpacks. Our water supply is stored in polyethylene bags inside the backpacks, which don't touch the rock outcroppings during the haul, so we're not worried about our water. We stop for the night. The second rope team's platforms are suspended on an outer corner of the wall, and down jackets don't protect our comrades from the cold, piercing night wind. "Africa by day — Antarctica by night," we joke.

August 15

August 15. We now look calmly at the 20-meter overhanging wall. Not a single handhold. We know that it's now easier to continue than to turn back towards the summit. "The Rubicon is crossed," notes Chernosliven. Again, the sun beats down mercilessly, and our swollen and scratched hands ache. Our legs feel like they're filled with lead; even a light touch causes sharp pain. The first climber on the route used a belay stance for most of the ascent. A large part of the wall is behind us, and it's now clear that the ascent will be completed.

We stop for the night. Again, the sound of a primus stove on its platform. We pour tea into flasks and lower them on a rope to the lower rope team.

August 16

August 16, 5:30. Our "meteorologist" Senachev informs us of "good news" — it will rain. This means that his left ear was ringing during the night. Again, we conquer the wall meter by meter. Finally, we emerge onto a large ledge and, for the first time in three days, have breakfast together. The rest of the route goes via extremely difficult rocks, but without the need for a belay stance. As we emerge onto the shoulder, Senachev's prediction comes true — it starts raining. But it doesn't dampen our joy. In celebration, we drink the last two liters of water. Later, we regret this, as we have to melt ice for dinner. At last, we sleep in a horizontal position. But due to the intense cold, we rise before dawn and, armed with duralumin pitons, begin our descent to the Base Camp (the group didn't bring ice axes or crampons). We receive a warm welcome from the observation group. And, packing our backpacks to the limit, we descend to the "Uzunkol" alpine camp.