Passport

- Technical class

- South America, Patagonia

- Cerro Torre summit via the southeast ridge by the "Compressor" route.

- Approximate complexity category 6B

- Route wall section length — 1453 m.

- Section length from the glacier to the Col of Patience saddle — 630 m. Route length from the glacier to the summit — 2233 m.

- Length of sections with 6th complexity category — 568 m.

- Length of sections with drilled holes (not included in point 7) — 465 m.

- Heights: Route start height (above sea level) — 1900 m. Summit — 3128 m. Height difference — 1228 m.

- Average steepness of the route wall section (R11–R40) — 80°.

- Equipment used: Friends — 185 pcs. Stoppers — 172 pcs. Rock pitons — 52 pcs. Copperheads — 5 pcs. Skyhooks — 9 pcs. Maestri pitons — 430 pcs. Ice screws — 47 pcs.

- Working hours including route processing — 66 h. Number of working hours during the ascent (from bergschrund R11 to bergschrund, non-stop) — 40 h.

- Nights spent in bergschrund (R11) — 4.

- Start of route processing — January 23, 2002. Summit reached — January 31, 2002. Return to base camp — February 3, 2002.

- Team leader — Seryogin Arkady Borisovich

- Participants: Lastochkin Alexander Nikolayevich

Free Wind at Superior Pass, or Memories of a Three-Week Great Storm

"Not forever to climb, there's a summit! Let's sit down, dangling our legs, To pass through such a steep slope Is not given to many". (Old mountaineering song)

Above — the icy vault of a cave. The temperature in this enclosed space ranges from +2 °C to −2 °C. Another gust of wind raises the tent made of special non-permeable fabric above the snow.

The snow cave is completely isolated from the outside world. Thick, strong walls made of firn are covered with a crown of ice. The bed, raised by 70 cm, can withstand a concentrated load of 5 people.

And yet this furious hurricane wind, caused by sharp pressure drops, somehow penetrates under us and lifts the "caremat" and the tent. At the same time, all five of us feel our ears popping simultaneously — just like during a sharp descent in an airplane. We have to swallow saliva to restore our hearing. The needle on our barometer sharply deviates by 1–2 bars at this moment, and then returns to its original, chronically low position.

It's already the second week of our stay on this pass, forgotten by God and people, and the goal hasn't come any closer. But some understanding of the strip of land on the edge of the earth called Patagonia begins to emerge. Driven by the Earth's rotation:

- moist air masses move freely from West to East over the surface of three oceans between the "roaring forties" and "furious fifties";

- they simply crash onto this Andes-crossed piece of continent;

- cold air masses flowing from the Antarctic ice dome through the Drake Passage are swirled into incredible hurricane spirals by the winds.

In the form of daily rain or snow, moisture settles in the mountains, forming a powerful glaciation.

For the fifth week now, we have been stuck at the edge of this (over 1 km thick!) ice shield of Patagonia under the peak of Fitzroy, and we're learning glaciology. It turns out that the Fedchenko Glacier in the Pamir and Baltoro in Karakoram are not the longest high-mountain glaciers in the world. Can they compare with the ice fields of Hielo Continental, stretching almost 400 km in length and 80 km in width! Its main glaciers:

- Chilean glaciers descend to the ocean level in the canyons of the western coast of South America.

- Eastern glaciers end in the lakes of the semi-desert pampa, where ostriches, guanacos, and llamas roam.

- In the foothills' forests live parrots.

It all started so well. After being delivered by five horses from Chaltén to the "Rio Blanco" alpine camp on December 22, we broke a trail to the Superior peak in just 8 hours through half-meter-deep snow, overcoming a difference of over 1000 m on December 24. On December 27, in a neighboring gorge, under harsh weather conditions, we conquered the beautiful peak of Saint-Exupéry via a new route with a complexity of at least "5B". And the night (from 7:00 PM to 6:00 AM) successful descent of eight people down a sheer kilometer-high wall gave hope for the correct choice of tactics for ascending the mysterious peaks of Patagonia. On December 30–31, a delivery was made, a cave was dug, and the first night was spent on the Superior Pass. Welcoming the New Year 1997 in a green beech forest, we still didn't know that the not very pleasant weather and wind on Saint-Exupéry were ideal conditions for climbing here, that they continue throughout the season, and that the limit of favorable days is almost exhausted. Snow, thickly covering the bright South American vegetation on January 2, cooled our pleasant memories of 40-degree Buenos Aires, located 2500 km to the north, and brought us back to the New Year's winter Russia.

Life in a snow cave, when you're cut off from the whole world by hurricane winds and snowstorms, and avalanches block the descent to the base camp, is not very joyful. The last 3 issues of the "Free Wind" newspaper, which V. Shataev had prudently supplied us with at the Russian State Sports Committee before our departure from Moscow, have already been read multiple times, as well as 4 issues of "SPID-Info". We have memorized the names of the editorial board, phone numbers, addresses, and circulations of popular newspapers among us. We had to give up participating in the celebrations on January 14 in the city of Mendoza and at the base camp under Aconcagua, dedicated to the 100th anniversary of the conquest of continents.

Oh, the weather messed up all our plans. A ski descent was planned from the summit of Aconcagua, with skis specially brought from Russia. But our friends from the Czech Republic, who recently appeared at Rio Blanco, categorically refuted this possibility due to the lack of snow. What a striking contrast with Patagonia! That's when a fantastic project was born — a descent from the bergschrund of the Eastern wall of Fitzroy under the Italian Window through the glacier Pedros Blancos, Superior Pass, glacier De Los Tres to the corresponding moraine lake. This is about 8 km of snow, ice crevasses, rocky-firn ridge, avalanche slopes. When Fitzroy (or rather the weather) again repelled the attempt to attack its impregnable walls, this project was implemented. It was a unprecedented descent through a snowstorm, sometimes on the crests of avalanches, of three people. Two of them — N. Arzamasstev and V. Igolkin — descended alternately, passing skis to each other. And S. Soldatov overcame the entire path, except for 20 m of steep rocks, in a confident and reliable style, without removing his skis.

One of the most important programs of the expedition was a sea reconnaissance of the Magellan Strait, the coast of Tierra del Fuego, and Cape Horn for a round-the-world journey on a yacht. It was led by yacht captain L. Belevsky, a professor of MSMA, who had twice crossed the Atlantic Ocean on a yacht built with his own hands in Magnitogorsk. The weather threatened this part of the program. So it was decided to split up, and four expedition members left for Tierra del Fuego. Now the assault five were connected to the world only through 3 radio communication sessions per day, conducted by the only remaining participant from MSU, V. Popovnin, who continued to study the De Los Tres glacier under the UNESCO program.

On January 31, after February 1, both groups were to reunite on the Atlantic coast in Rio Gallegos to travel north to Argentina and storm Aconcagua. Today, January 24, the hurricane wind and snowfall are keeping us inside the cave, not even allowing us to go out for a "shxeldu". But the decision has been made. Tomorrow we will storm the summit. Despite the weather, despite the fact that the wind grinds absolutely new mountaineering ropes over the day, despite the unpleasant meeting with a climber who died last year... He, along with the glacier, is slowly moving towards the ice ledges, and these constant hurricanes and complex relief do not allow him to be lowered and buried. But nothing can stop us now. The whole team is fully confident in their strength, in victory.

The scientific sports expedition of the Alpine Club of Magnitogorsk, consisting of 10 people, worked in South America from December 16, 1996, to February 23, 1997. Its participants traveled along the entire Atlantic coast of the Argentine part of the continent to Tierra del Fuego and further to the area of Cape Horn. The study of Patagonian glaciers, started in 1996 by an international glaciological expedition led by V. Popovnin, was continued.

Climbers have passed a new complex route on the mountain St-Exupery. For the first time, a Russian group (according to available information — the only one this season) consisting of:

- M. Sybaev,

- S. Soldatov,

- A. Ivanov,

- V. Igolkin,

- R. Zaitov

set foot on Fitzroy. The peak of Aconcagua was also conquered by L. Belevsky, A. Volodko, N. Arzamastsev, and up to 6500 m — by Yu. Stroganov.

As part of the scientific and cultural-educational program, the expedition got acquainted with:

- Central Andes,

- Patagonia,

- Tierra del Fuego,

- South American pampa,

- jungles,

- military garrison and mineral water springs of Puente del Inca,

- provinces of Santa Cruz, Mendoza, Carmen,

- world-famous Iguazu waterfalls,

- Latin American carnival.

Collections for the Museum of Earth History were gathered, and 18 hours of video materials were shot, including unique ones — on the walls of St-Exupery, Fitzroy, and Aconcagua.

The expedition was sponsored by:

- Magnitogorsk Iron and Steel Works

- JSC "BIG" (Magnitogorsk)

- "Magtollmet" (Moscow)

- "Hercules" (Togliatti)

- administration of Magnitogorsk.

High-quality equipment was purchased from "Alpindustriya" and "BASK" (Moscow).

V. Igolkin, head of the scientific sports expedition.

Akhmedhanov Timur Kamilievich

- Coach: Yuri Pavlovich Tinin

- Federation of mountaineering and rock climbing of Moscow

Cerro Torre (3128 m)

Patagonia is a mountainous country stretching 1770 km along the Pacific coast of South America from south to north, starting from the Magellan Strait.

The group of peaks Fitz-Roy and Cerro Torre is located just 410 km from the Magellan Strait.

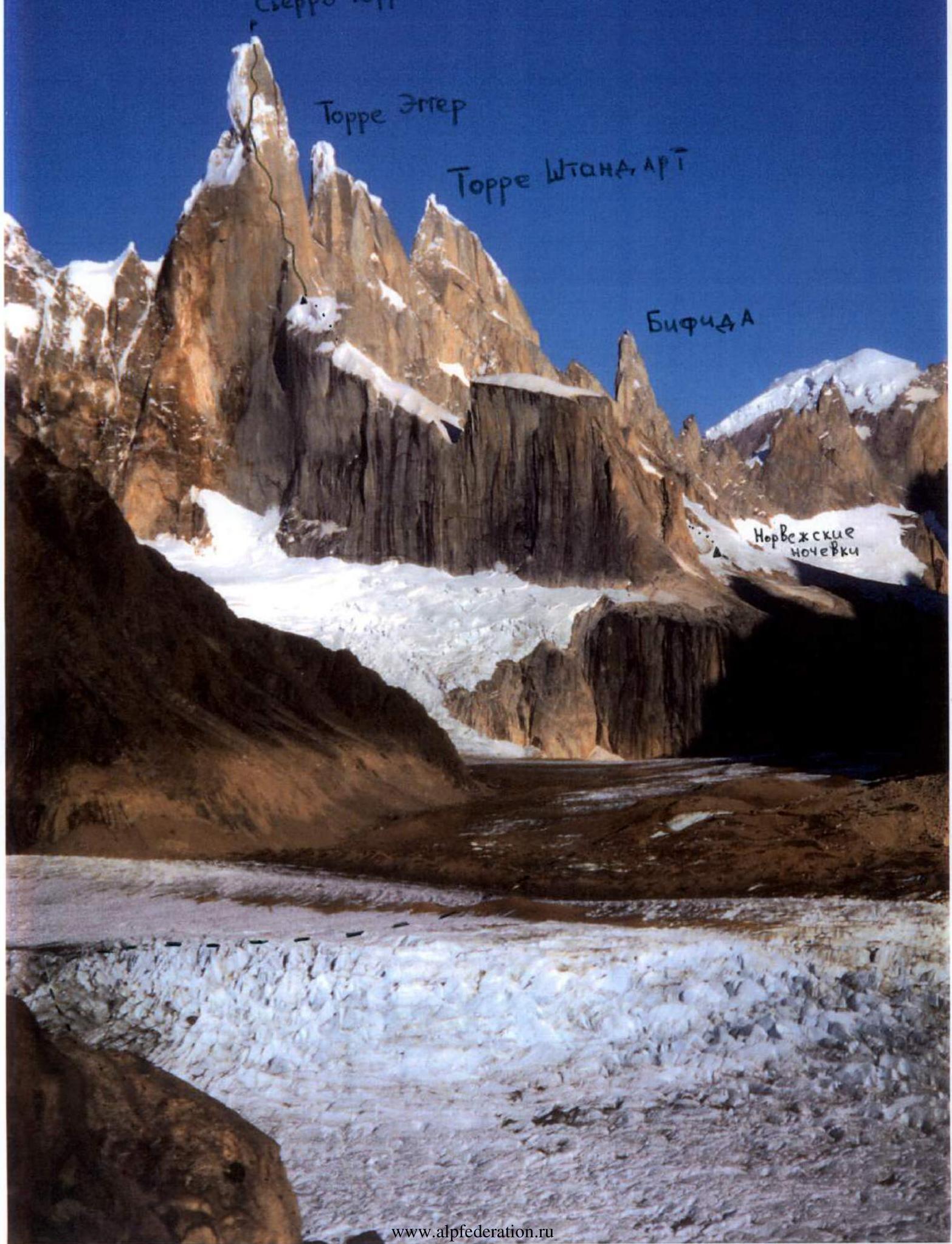

The Cerro Torre massif borders the Patagonian ice sheet Hielo Continental (Hielo Sur) to the east, which is 400 km long and about 100 km wide, with an ice cover thickness of up to 1 km. The nearest fjord with Pacific waters is only 30 km from Cerro Torre. The moist western wind, crossing Hielo Sur, cools down, and precipitation in the form of snow falls precisely on the chain of peaks:

- Cerro Torre,

- Torre Egger,

- Torre Standart.

This explains the very strong glaciation and significantly worse weather in this zone compared to the climatic conditions on the Fitz-Roy massif, located just 3–4 km east of Cerro Torre. To the east of the Cerro Torre and Fitz-Roy massifs lies the flat pampa, stretching to the Atlantic Ocean. The Cerro Torre and Fitz-Roy massifs are located at 50° south latitude.

Patagonia is the only land area on Earth completely open to circumpolar air mass circulation. Cold air masses flowing down from the Antarctic dome at 40–50° south latitude, colliding with air flows from equatorial zones, create a special zone of "roaring forties". Air hurricane winds freely circle the Earth without encountering any obstacles on their path except for a narrow strip of land where Patagonia is located. The cold Humboldt current, rising from the shores of Antarctica along the western coast of South America, has a significant impact on Patagonia's weather formation.

From Alan Kearney's book "Climbing in Patagonia" (Seattle, 1993): "Due to Patagonia's unique location, being the only obstacle to air mass movement in the zone of 40–50° 'roaring forties', Patagonia has recorded 80 days per year with wind speeds of 79 km/h. Winds with speeds of 150–200 km/h are not uncommon. Good weather is an exceptional state in Patagonia; for example, according to Climbing magazine, during the summer season from November 2000 to February 2001, good weather lasted... 12 hours".

Until 1970, the Cerro Torre peak was considered one of the most challenging peaks in the world.

The first ascent of the peak is attributed to Italian Cesare Maestri and Austrian Toni Egger in 1959. However, a significant part of the global mountaineering community strongly doubts this fact. In particular, Austrian Tommy Bonapace, from the same town as Egger, dedicated 15 expeditions to attempting to climb the north wall of Cerro Torre. His best result was reaching a point 300 m from the summit. He stated that he couldn't find any logic in the route described by Maestri.

In May 1970, at the beginning of the Patagonian winter, Maestri's team began working on the southeast ridge of Cerro Torre. The expedition was sponsored by "Atlas Copco", with $12,000 allocated, as well as a 60-kilogram compressor for drilling holes for pitons. 70 days were spent on the wall. Every rope was led by Maestri exclusively. Winter took its toll, and the Italians retreated, not reaching the summit by 450 m. To not waste time, the team moved to Rio Gallegos, the nearest major city in Argentina, for the winter. Five months later, in November, the team returned to Cerro Torre. Climbing up the fixed ropes to the point they reached in the winter, the Italians discovered that they had forgotten the entire set of rock pitons in the camp. Instead of returning down, they drilled holes and hammered 350 pitons into the key wall. Having passed the key, at the upper anchor station, Maestri forbade team members from approaching him. He did not attempt to overcome the giant ice cap of the "mushroom" and on the descent, he knocked out all the pitons on the last rope, suggesting that subsequent climbers do the same. He argued that he didn't climb the ice cap because it is not actually the summit, as it will be blown away by the strongest Patagonian winds, which often reach speeds of 200 km/h.

The history of Cerro Torre is full of tragic unfulfilled hopes. Climbers spend 15–19 expeditions attempting to climb it, but traditionally stormy weather in the "roaring forties" has stopped many within dozens of meters from the summit... Currently, only three routes have been fully completed on Cerro Torre:

- the "Compressor" route via the northeast ridge,

- the "Ferrari" route via the west wall (1974),

- the "Devil's Directissima" via the north wall (Silvio Caro, 1986).

Only the "Compressor" and "Ferrari" routes have been repeated.

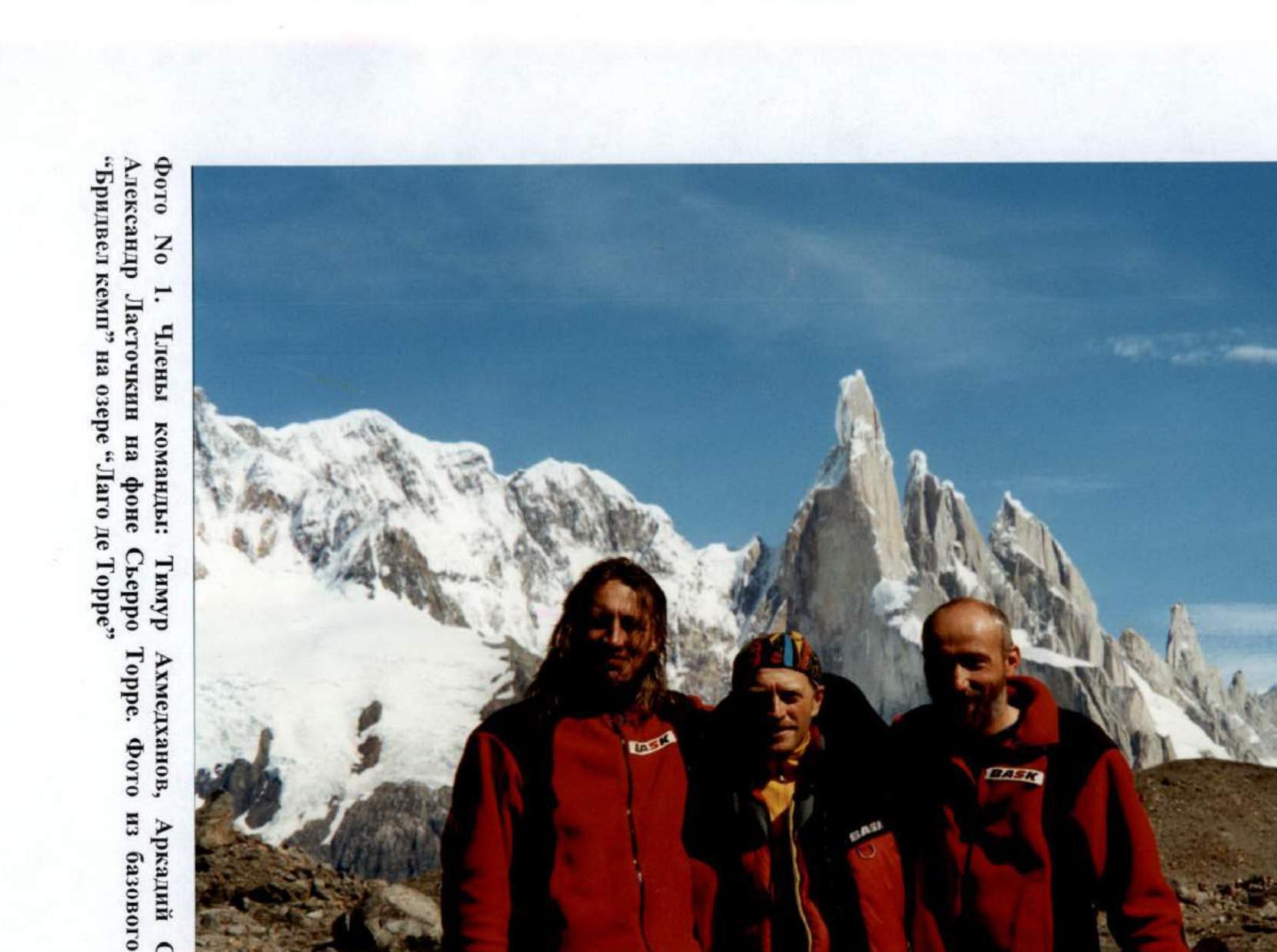

Photo #1. Team members: Timur Akhmedhanov, Arkady Seryogin, Alexander Lastochkin against the backdrop of Cerro Torre. Photo from the "Bridwell Camp" base camp on "Lago de Torre" lake.

Route description by sections

The approach to the route takes 2–2.5 hours of walking from the Norwegian campsite along the closed Torre Glacier.

Sections R0–R11 lead to the Col of Patience saddle. The exit to the saddle is ambiguous and depends on the degree of glaciation. The team received recommendations from Alex Huber.

R0–R1. The bergschrund is overcome via a snow bridge. Further, along a snow-ice slope with a steepness of 50–55° to the rocks.

R1–R2. Movement along a snow-ice slope with a steepness of 55° along the rocks. Section length 100 m. An insurance point is set up on the rocks.

R2–R3. Movement along a narrow ice edge between the rocks and the bergschrund. Steepness 55°.

R3–R4. Movement along a narrow ice edge between the rocks and the bergschrund. Steepness 55°.

R4–R5. Movement along a narrow ice edge between the rocks and the bergschrund. Steepness 55°. At the moment when the bergschrund sharply turns left, the direction of movement leads into a narrow 65° couloir to the right and upwards. Exit to the rocks.

R5–R6. Movement along a snow-ice slope with a steepness of 60° to a vaguely expressed rock inner corner. Along the corner — complex climbing (6C). The team used a rope fixed by Alex Huber.

R6–R7. Movement along the rocks with an exit to an ice slope with a steepness of 65°.

R7–R8. The rocky massif is bypassed on the ice to the right, then vertically upwards along the ice ridge. Section length 90 m. The rope is extended.

R8–R9. Movement along icy rocks vertically upwards to a snow-ice slope. An insurance point is organized on the rocks.

R9–R10. Exit along a snow-ice slope to the Col of Patience saddle.

R10–R11. Along a snow-ice ridge — exit to the bergschrund. In the bergschrund, a bivouac can be organized for 6–7 people. The team set up a storm camp in the bergschrund with a sufficient supply of food and fuel to wait for better weather. From a tactical point of view, it is better to wait for better weather here, as practice has shown that a period of good weather lasts no more than a day and a half. Passing the Torre Glacier and sections R0–R11 takes a lot of precious time and effort (the team witnessed unsuccessful attempts by a Japanese pair, who didn't climb Cerro Torre even after 3 months. A team of Swedes was forced to retreat twice, once — from the compressor (!!!). They all started each time from the Norwegian campsite).

It should be noted another feature of Cerro Torre. During bad weather, the entire peak is covered with an ice shell due to high air humidity. On the first good day, which must be used for the ascent, all this ice melts and falls down. Sections R22–R31 are particularly affected.

R11–R12. Movement vertically upwards along the wall with a steepness of 85° through a system of crevices.

R12–R13. Continuation of movement along the wall. A series of crevices is passed using ITO.

R13–R14. Movement along an inner corner. ITO is used.

R14–R15. Movement along the wall, then exit to an inner corner, and further to a rib.

R15–R16. Movement along a mixed relief rib.

R16–R17. Vertical wall with a narrow crack. Use of ITO. The section is called "Bana Kræk".

R17–R18. Movement along a rib. Mixed relief.

R18–R19. Chimney with a plug. Passed on the right side of the chimney.

R19–R20. Continuation of movement along the wall vertically upwards. Complex free climbing 6C.

R20–R21. Exit to a snow-ice slope. An insurance point is set up on a rocky belt.

R21–R22. Movement along simple rocks vertically upwards.

R22–R23. Continuation of movement along simple rocks towards a vaguely expressed inner corner.

Sections R23–R27, R32, R33, R35–R38 are drilled by Cesare Maestri's team during the first ascent in 1970–1971 with rock Cassini pitons installed in holes drilled with a compressor (gasoline compressor from Atlas). The depth of the holes is 1–1.5 cm. It should be noted that due to metal corrosion, the pitons sometimes fly out. In the description, these pitons are called pitons, although they have nothing in common with expanding pitons.

The section R23–R26 is called the "monument to the piton road". The piton road goes along a vertical monolithic wall from left to right at an angle of 45–60°. This section is dangerous due to constantly falling ice from above.

Descent along the section R23–R26 does not allow the use of a rappel rope, so the team had to pass the piton road on the descent using ladders.

R25–R26. The piton road leads to a 50 m long chimney covered in ice. There are no pitons in the chimney. Ice constantly falls from above. Section length 63 m. The section ends with a 0.4×4 m ledge. This is the only place on the R12–R40 section where a bivouac can be set up. During the ascent, the team left backpacks with bivouac equipment and gas on this ledge to reduce weight and increase maneuverability. From the practice of Cerro Torre ascents, it follows that many teams make one bivouac in the bergschrund R11 and another on the R26 ledge.

R26–R27. From the ledge, 20 m vertically upwards along the piton road. Further, along an ice slope 75° to the rocks.

R27–R28. Complex climbing along icy rocks. Use of ITO. Exit to an ice slope 75°, then vertically upwards to a rocky belt.

R28–R29. Traverse along the ice to the right along the rocks to an ice couloir.

R29–R30. Icy rocks. Many Patagonian ice mushrooms create potential danger. Movement is vertically upwards.

R30–R31. Along an ice slope vertically upwards to the rocks, then along the rocks, traverse left along the ice with an exit to the southern side of the "ice tower" (sections R27–R34 — exit to the "ice tower"). Special attention should be paid to this section on the descent, as it is easy to get lost on the south wall.

R31–R32. Movement along the piton road vertically upwards.

R32–R33. Continuation of movement along the piton road.

R33–R34. 15 m vertically upwards along the piton road, exit to the ice ridge of the "ice tower". Along the ridge to a snow plug, then transition to the wall of the summit tower. On the descent, there is a risk of the leader slipping into the chimney formed by the ice tower and the wall of the summit tower. Sections R33–R37 are potentially dangerous due to the risk of the southern summit mushroom collapsing (in the photos, it is on the left. The northern mushroom is the summit).

It should be noted that after the bad weather on February 5, 2002, it was discovered that the southern mushroom had collapsed.

R34–R35. From the insurance point, 15 m upwards and to the left by free climbing (6C), then using ITO (stoppers, pitons, friends) movement towards the compressor.

R35–R36. Movement along the piton road.

R36–R37. Movement along the piton road.

R37–R38. Movement along the piton road. Exit to the compressor, where the R38 reinsurance point is located. The compressor hangs on a steel cable on five pitons. Icicles forming and periodically falling from the compressor pose some threat to climbers on sections R34–R38 (there was a case where an icicle knocked down a leading German climber).

When the team reached the compressor (time 20:00), the weather began to deteriorate sharply: sharp gusts of wind from the Pacific Ocean (from the west), snow charges.

The danger of ascending Cerro Torre from the east lies in the fact that bad weather always comes from the western coast of the continent, and on the eastern slope, it is practically impossible to fix the approach of bad weather. (Point R32 is the only place from which the Hielo Sur glacier is visible to the west of Cerro Torre. At the moment when the team was at this point, nothing foretold the approach of bad weather).

R38–R39. 3 m upwards along pitons, then complex ITO climbing using copperheads, skyhooks, rivet hangers. (During the first ascent, Cesare Maestri drilled this section with a compressor, but on the descent, he cut down all the pitons at the root. It should be noted that Maestri forbade all members of his team from passing this last rocky section of the route). The insurance station is located at the top of the "headwall" of the summit tower, set up on one piton and one bolt without a loop.

R39–R40. Passing the summit mushroom. The shape of the ice mushroom changes greatly from season to season. Often it becomes impassable. Sometimes it collapses (English climber Kevin Tau witnessed the collapse of the northern summit mushroom in 1992). In the summer season of 2001–2002, the condition of the summit mushroom was ideal for its passage. The team leader climbed the mushroom along the southern slope using ice tools, spending 30–40 minutes on this. At the summit, an ice axe with a loop was found, left by Alex Huber. Alexander Lastochkin stood on the summit of Cerro Torre at 22:45–23:00. By this time, visibility was zero due to darkness and a storm, so no photographs were taken (the last photo was taken at the compressor).

P.S. 1) During the descent on sections R11–R39, special attention should be paid to the rope, especially during a storm when the rope is thrown upwards like a candle. There is a risk of the rope getting stuck (the team's rope got stuck on sections R35, R28, R17).

- Before ascending Cerro Torre, lubricate the jaws of carabiners and moving parts of friends with antifreeze lubricant, as in the case of Patagonian bad weather, everything is covered with ice, and carabiners with friends do not work. This happened to the team on the descent (see Lastochkin's photo on the descent). It should be noted that the ropes are also covered with ice and do not pass through rappel devices (using "eight" figures is undesirable due to the risk of twisting and jamming ropes when pulling them). At some point, the icing of equipment became critical for the team (point R23 on the descent): carabiners were difficult to open and close, ropes became so thick that using rappel devices became impossible. A wind with gusts up to 150 km/h (according to the national park service), lasting 2 hours and not allowing the team to move, blew away all the ice, and the team was able to continue the descent after the wind died down.

Photo: Climbing №185, May 1999 (from the summit of Fitz-Roy) — "Compressor" route — "Devil's Directissima" route.

Tactical actions of the team

Team composition: Timur Akhmedhanov, Alexander Lastochkin, Arkady Seryogin (together passed the Reticent Wall route on El Capitan with a complexity of A5). At the last moment, V. Skripko joined the team. However, after the first ascent to the Col of Patience saddle, due to knee problems and physical unpreparedness, Skripko refused to continue participating in the ascent.

The team arrived in El Chaltén on January 12, 2002. Then, the delivery of equipment and products to the "Bridwell Camp" base camp, located 10 km from Chaltén on the shore of the moraine lake "Lago de Torre", was carried out. The ascent to the summit of Cerro Torre via the "Compressor" route is made from the "Norwegian campsite", located 10 km from the base camp directly under the Torre Glacier, flowing from the cirque of peaks Cerro Torre and Torre Egger. The Norwegian campsite is a cave dug under large rocks (tents are not set up in this place due to strong winds). When moving from the base camp to the Norwegian campsite, 4 glaciers need to be crossed. At the time of the team's stay in the area, the glaciers were open.

The approach from the Norwegian campsite to the start of the route is made along the closed Torre Glacier in 2–2.5 hours.

On January 18, the first exit to the Norwegian campsite was made, as well as under the beginning of the route along the Torre Glacier. The delivery of food and equipment was carried out. The onset of bad weather forced the group to return to the base camp on Lake Torre.

On January 23, 2002, the team began moving along the route at 5:00 (the approach was made from the Norwegian campsite). The exit to the Col of Patience saddle is extremely ambiguous and depends on the degree of glaciation of the route.

The team received recommendations from Alex Huber, who passed the "Compressor" route ten days earlier. The exit to the saddle is a movement along snow-ice and rocky terrain of medium complexity. The length of this section is 630 m.

The exit to the saddle and further to the bergschrund took place at 15:00. A storm camp was set up in the bergschrund. By 19:00, 3 ropes were processed and fixed on the rocky section R12–R14. The weather began to deteriorate. At 20:00, American Dean Potter, who had made a solo ascent to Cerro Torre, returned to the bergschrund. He had very scarce bivouac equipment (absence of any, except for an emergency non-gortex bag). He was offered a warm "Bask" jacket, which he readily accepted. (Later, he wrote in the Climbing magazine about how he was cold in the bergschrund and how "the sight of packed Russians" didn't warm him up. He somehow forgot to mention that he was offered a warm jacket...)

On January 24, the team stayed in the bergschrund, waiting out the bad weather. On January 25, the bad weather continued, and it was decided to descend, leaving food and some equipment in the bergschrund (a double rope was pulled out from section R12).

From January 25 to 28, the team waited out the bad weather at the base camp on Lake Torre. On January 28, at 17:00, the weather improved, and the team urgently moved to the Norwegian campsite. On January 29, a storm, and the team was forced to stay in the caves. On January 30, at 4:00, the team left for the route. By 14:00, they were already in the bergschrund on the Col of Patience saddle. From 15:00 to 20:00, sections R12, as well as R15 and R16, were hung with ropes (it should be noted that during the period of bad weather from January 24 to 29, the perlon ropes were not cut). In the evening of January 30, signs of deteriorating weather appeared.

On January 31, the team started from the bergschrund at 4:00. The hung ropes on sections R12–R16 allowed for quick advancement along the route. Each participant carried a backpack with a gortex bivouac bag, warm clothes, food, and a gas burner. When at point R21, the weather began to deteriorate, but after some time, it improved again. When exiting to the ledge on section R26, it was decided to leave backpacks to increase mobility. Water, some food, and flashlights were taken. Sections R23–R27 are constantly hit by falling ice. Sections R28–R31 represent complex climbing along icy rocks and ice. Many Patagonian ice mushrooms have a cellular structure, similar to bird feathers. When exiting to point R31, one could see the Hielo Sur glacier. Nothing foretold the deterioration of the weather.

Movement on the route was carried out alternately: the leader passed the section, fixed the ropes, then the second participant passed, cleaned the route, — the last participant. The complexity of the route, as well as the falling out of Maestri's pitons on the piton roads, did not allow the team to move simultaneously, as some Western climbers recommend.

On sections R23–R27, R31–R33, R35–R38, "pitons" are hammered, representing Cassini rock pitons with a nail length of 1–1.5 cm, installed in holes drilled with a compressor. Due to metal corrosion over 30 years, some pitons fly out when loaded. When the team reached the R38 insurance point, located right on the compressor, the weather began to deteriorate sharply: a strong western wind with snow started. The compressor is a monstrous structure attached to five pitons. Two people can stand on it freely. Icicles constantly form on the compressor and fall down (a threat to climbers on sections R34–R38). The last photos and video shots were taken at the compressor (the video camera was broken). The passage of section R39 was carried out using skyhooks, copperheads hammered into microcracks, as well as small rock pitons (this section was drilled with pitons, but Maestri cut them down on the descent). The team reached point R39, located at the very top of the "headwall", at 22:15–22:30 on January 31. It was already dark, and a strong wind with snow was blowing, visibility was zero.

- Akhmedhanov Timur began organizing a rappel loop.

- Alexander Lastochkin climbed the summit mushroom along the southern slope, spending 30–40 minutes on this (the team was guided by Alex Huber's recommendations).

- At the summit of the mushroom, an ice axe with a loop was found, left by a pair of German climbers.

- Visibility was zero. Immediately after reaching the summit, Lastochkin descended down the double rope.

The team began an immediate descent at 23:00–23:15. The descent was extremely difficult due to the storm:

- ascending flows constantly threw the ropes upwards, creating a risk of their getting stuck, which periodically happened, forcing the team to "climb" to the stuck end with lower insurance (the team had three 10.5 mm × 60 m ropes during the ascent in case one of the ropes got hopelessly stuck).

At 4:00 on February 1, the group returned to the ledge at point R26. The passage of the piton road R26–R23 took 7 hours due to:

- the continuation of the storm,

- constantly descending avalanches along the wall,

- the impossibility of using a rappel rope due to the 60-degree slope of the road,

- icing of ropes, which did not pass through rappel devices,

- carabiners, which were difficult to open and close.

When the team gathered at point R23, wind gusts intensified to 150 km/h (according to the national park administration, received later), which forced the team to stop moving.

The wind continued for about two hours, blowing away all the ice from the rocks and equipment. Due to the high humidity of air masses coming from the Pacific Ocean, everything quickly became covered with a peculiar ice:

- first, ice threads 1.5–2 cm long formed, with a fringe that was hard to wipe off.

- then, at some point, this fringe froze, forming a thick layer of ice.

- These processes are the reason for the peculiar shapes of Patagonian ice mushrooms.

By 12:00, the wind speed decreased, and