5.2

Ascent Passport

- Ascent class — technical ascent

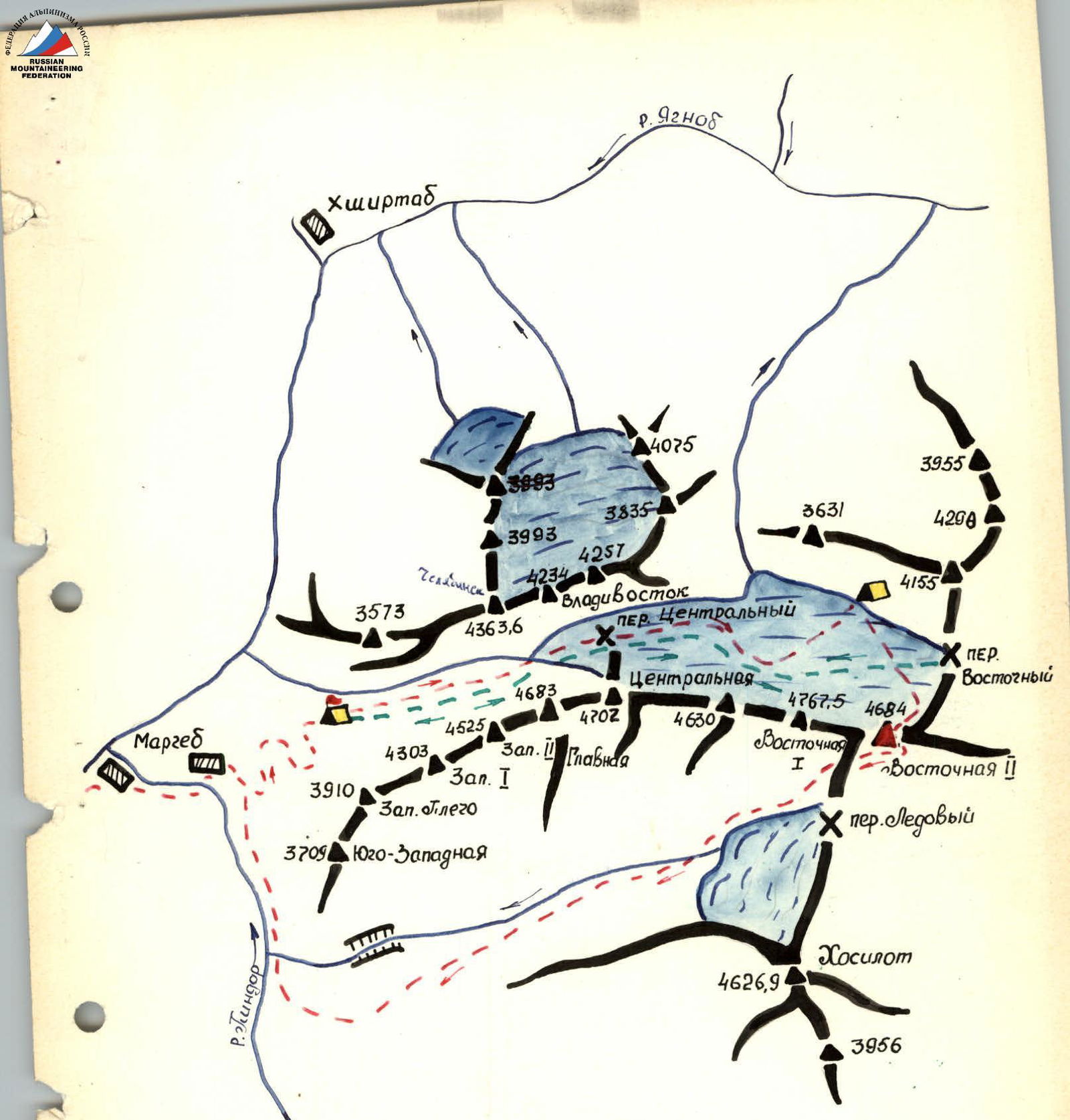

- Ascent area — PAMIR-ALAI, HISSAR RANGE

- Ascent route — ZAMIN KAROR EASTERN-II 4554 m, from the north via the edge

- Ascent characteristics: height difference — 1204 m, average steepness 59°, length of complex sections — 830 m.

- Hooks used: rock — 123, ice — 11, bolt — 0

- Total hours on the route — 25.3 hours

- Number of overnight stays and their characteristics — 2 bivouacs

- Team name: team from Chelyabinsk Regional Council of the Spartak Voluntary Sports Society

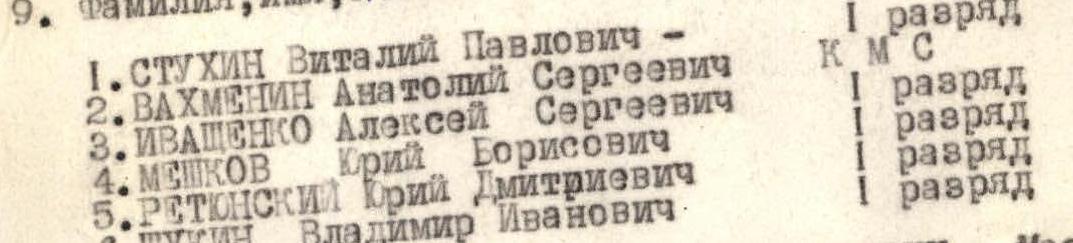

- Surname, name, patronymic of the team leader, participants, and their qualifications

- STUKHIN Vitaly Pavlovich — 1st sports category

- VAKHMENIN Anatoly Sergeevich — Candidate for Master of Sports

- IVASHCHENKO Alexey Sergeevich — 1st sports category

- MESHKOV Yuri Borisovich — 1st sports category

- RETYUNSKY Yuri Dmitrievich — 1st sports category

- SHCHUKIN Vladimir Ivanovich — 1st sports category

- Team coach — LEVIN MIKHAIL SEMENOVICH — Master of Sports

- Dates of departure and return — July 21 — departure, July 23 — return, 1976

Scheme №2. Conventional Symbols

Base camp "2600" Ascent camp "3500" — Team's path — Path of the reconnaissance group on July 13, 1976

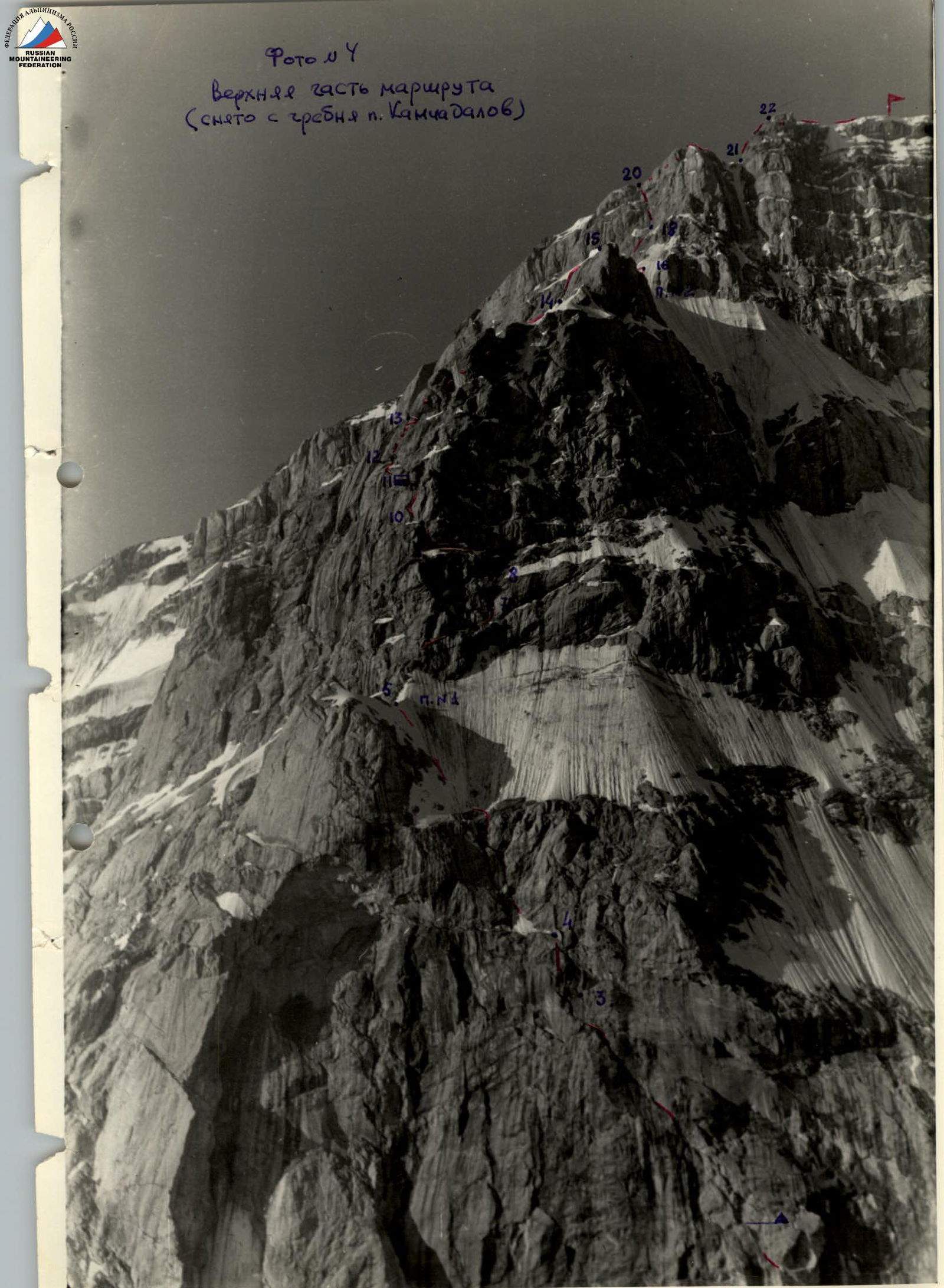

The first landmark is a slit starting under an overhang and going up-left through the wall of the counterfort to a snow-ice couloir between rock cornices at the top.

As early as possible (rocks!), having passed the snowy ascent and overcome the 1.5 m randkluft before the light pink rock "forehead", enter the "forehead" from the right via an angle 2 m and traverse left 20 m along a smooth, wet shelf.

Here is the beginning of the slit:

- a vertical chimney with a plug

- turns into an internal angle with smoothed walls

- finally, the crevice leads to a platform with a control cairn

Total along the slit — 120 m.

Behind the platform, a 3-meter internal angle leads to a 20-meter gray wall. Up the wall to a narrow, intermittent shelf and left along it, traverse 10 m to an inclined internal angle going up-left, leading to a shelf, in the middle of which there is a chip. Along the shelf — 100 m. Very wet!

From the chip up the wall 20 m under the brown overhang, bypass it on the left and further up 20 m along the wet wall with smoothed holds and 20 m along the dry monolithic wall to a large stone at the beginning of the ice couloir.

Along the right (here and further along the route) edge of the ice and the vertical wall of the couloir to a large stone-"plug" 70 m, and behind it to the left branch of the couloir — 40 m.

Further along the long snow-ice ascent to the right part of the snowy saddle of the northern edge — 100 m. In the lower part of the ascent, there is about 0.5–1 m of snow on the ice base, higher — practically no snow.

Movement from one rock "island" to the next. On the saddle, an overnight stay on a snowy platform is possible.

From the saddle along moderately complex rocks up 60 m under a large overhanging internal angle, which can be bypassed by traversing right 40 m along an intermittent shelf-chip.

Further 30 m up along the internal angle and 30 m along a similar wet chimney with a plug to a platform under a 20-meter vertical monolithic wall.

The lower part of the wall overhangs (undercut), further — smooth and complex to a snow-covered scree shelf.

Along the shelf left 40 m, return to the edge of the northern edge to a 30-meter internal angle leading to the next shelf.

Along the shelf 10 m left to a wall with a vertical slit, gradually turning into a chimney. After 10 m on the left — an overhang, under which there is a platform for an overnight stay.

From the platform left 50 m to a snowfield and up it 40 m (gaps!) to the left branch of the couloir, along which rise 20 m to a short saddle in the eastern counterfort of the edge.

From the saddle up 20 m along a gray wall under an overhanging "forehead" and along a shelf, traverse left 20 m to the end, then up 40 m along a rock board of a steep ice "kolob". The lower part of the wall is monolithic and smoothed, in the upper part — "live" slabs.

Above the "kolob", a snowy slope begins, leading to the edge of the northern edge to a black rock belt.

Along the internal angle of the rock belt 50 m to a snowy 3 m snowdrift (a cornice is possible).

After the wall of the snowdrift, a sharp snowy ridge stretches, ending with an ice ascent 90 m.

Along the steep ice, rise up 70 m to a rock outcrop on the left, then:

- traverse left

- onto a snowy ridge 10 m along the main shelf 15 m to the entrance to a steep gully, from which the entrance to the eastern ridge of the summit is visible.

In the 100-meter gully, there is an alternation of walls and shelves with an abundance of "live" stones, then it turns into a 30-meter wet and smoothed internal angle with ice.

Along the angle with ice to a shelf 20 m. Further along a negative 20-meter internal angle, the right wall of which overhangs, and the left is practically devoid of holds and cracks. Here, a chain along a slit 3–5 cm is used with the help of:

- eccentric protection

- cams

- channel hooks

- ladders

bypassing the cornice 2 m. Pull up the backpacks!

On the eastern ridge, there are many scree platforms. Here is a bivouac.

Along the scree shelves to the summit tower to the west. The exit to it is along an internal angle. The highest point is a natural three-meter stone pyramid in the center of the scree summit plateau.

For the descent, return to the eastern ridge below the tower and traverse along a wide scree shelf to the watershed behind the ridge going from the summit to the south, to the Ledoviy Pass. From the ridge along scree and snow — descent to a stream.

Along the left bank of the stream to a canyon, which can be bypassed on the left along a trail, then descent to a pack trail along the Lindor River and ascent to the "2600" helicopter pad in the base camp.

July 19, 1976

The sun will not start warming soon, the mountains are sleeping. Vakhmenin and Stukhin leave the "2600" base camp at 5:00 under the walls of the eastern part of the Zamin Karor massif — where they were a week ago. Now they won't have to climb the Eastern Pass, the start of the route to Zamin Karor Eastern-II has already been determined. But how the snow cover has changed over the week! And on the Central Pass, there are sure to be open crevices and plenty of bare ice… The heavily loaded duo is gaining altitude.

Slowly, too slowly, the pass is approaching. Finally, their route is visible again — it looks beautiful! The western part of the massif is practically devoid of snow and ice — and you constantly feel that something is missing. Well, here, to the east, there is plenty of white color, so everything is fine, and it even resembles the walls of the Helda that overwhelmed them in 1974.

On the pass, a tent is left for observers; another, for the route, will be brought to the "Chelyabinsk Bivouacs" tonight by Ivashchenko and Shchukin. Along the familiar path, they begin their descent from the pass. Last time they climbed lightly, and now their backpacks are a significant hindrance. Still, after 20 minutes, the duo found themselves in a hollow in the middle of the glacier, having lost about 400 m of altitude and a considerable amount of sweat (they ate and drank a lot in the base camp for several days). It's already hot, the walls are "alive". Streams flow, fragments of ice and stones whistle, but not much is falling — almost everything has already come down. Vakhmenin is constantly whistling something — maybe it makes it easier for him to breathe?

Not a breath of wind. The hanging glacier to the left — above the "Black Triangle" — has warmed up and "started working" — it's already 11:00. Soon the duo reached the flat area of the "Chelyabinsk Bivouacs", which they had previously spotted. An excellent place! Here, without significant clearing, a team of badge holders can fit. There is both snow and water nearby, and most importantly, the lower part of the route wall is right in front of them.

One person observed and cooked lunch, the other went along the slope of the Kamchadal Peak and watched the wall from there. There weren't many stones — on average 4–5 per hour, and they all stuck into the snow below in the area of the bergschrund… The snow needs to be passed earlier. And further on the wall, we won't be bothered: its top overhangs, and all the "snowbirds", as we call them, will fly past our backs. Meanwhile, the hanging glacier is overfulfilling its quarterly plan — but all its efforts are pouring down the gullies much to the right of our counterfort wall. The wall now doesn't look like it did a week ago — the angle is different, and the lighting has changed. Black streaks catch the eye — it means there will be ice in the morning, and then water cascades of various calibers. All hope is on the morning sun — maybe we'll warm up…

Thus, not being distracted from the 20x telescope and 10x binoculars, they waited for lunch. As expected, the chief purveyor, Vakhmenin, began distributing products — let the other four first bring their backpacks, then we'll see. And on the Central Pass, there's still no one.

From different points, Vakhmenin and Stukhin indulged in the wall until the evening. And at 18:00, two silhouettes appeared on the pass. The place for the tent has already been chosen, the most cozy one, tea is being heated — if only they would hurry up, there's something to talk about, and it's more fun in a foursome.

Tomorrow morning:

- one duo will go for processing,

- the second will observe it, providing backup.

The first question to Shchukin: "How many ropes did you bring?" — thankfully, everything is in order here:

- 2 × 60 m + 70 m main ropes

- 60 m of Repschnur

- An excess of gasoline

Ivashchenko brought as many products as he could carry — we ate and drank our fill, prepared the equipment for the next morning's early departure, and went to bed together. Although, no: simultaneously, but not together — two lovers of fresh air slept on foam mats outside the tent.

Well, there are no rains here, and the down-filled sleeping bags, which were thoughtfully brought from Chelyabinsk, are still warming.

July 20, 1976

As planned, they got up at 5:00. Ivashchenko woke them up — as always, imitating his army sergeant-Lezgin: "Get up! Who's sleeping,…? Breakfast is ready", and soon the duo sorted out the radio stations "Vitalka", arguing over the one with a broken antenna — and parted ways. It's not yet 6:00, and Vakhmenin — Stukhin are already crossing the glacier. And here's the start of the ascent, initially almost imperceptible. A kilogram altimeter, Stukhin's special pride, shows 3450 m. They stood for a moment, connecting with a rope…

It's almost dawn. The snow is very dense, steps are difficult to make, but they hold normally. The Bergschrund turned out to be wider than they would have liked — so they went left to a bridge. Vakhmenin crossed the bridge and went up the slope. It was so steep that they literally touched the snow with their caps — and went on, sticking their hands into the snow. At 7:00 (oh, how much earlier they could have left!) they approached the rocks. But they couldn't reach them — there was a 1.5-meter-wide randkluft. They decided not to climb onto the pink rock "forehead" but to bypass it on the left along the ice to the beginning of the internal angle. The beginning turned out to be a natural deep chimney, further expanding and going up-left obliquely across the entire lower wall, practically to the junction of the "drop—bed" planes, i.e., more than half a kilometer.

Vakhmenin reached a small shelf, hammered in a hook, said: "Now I feel like a human being" and changed into galoshes. Then he descended and removed all the lower hooks.

The perlon rope was thrown directly onto the pink "forehead".

Vakhmenin climbed back to his previous spot and slowly undressed… everything went as in the training film by Mikhail Ivanovich Anufrukov, but then the ropes ran out.

— "What will we do next?" — "We'll go down, — Stukhin replied. — It's almost 11:00, and it will start snowing on the snow." They descended, secured the end of the perlon rope on a rock, and hung several dozen hooks for the next morning.

The last, 70-meter main rope, was secured with its lower end to an ice hook screwed in just above the bergschrund — it was frayed at the end, and a knot was tied there for now. But when measuring in the base camp, they estimated that if they cut it off on the day of departure, it would become only a couple of meters shorter than the other sixty-meter ropes. A double Repschnur attached to the same ice hook was enough to reach across the bridge — so tomorrow, when they go under their backpacks, there will be perlon ropes.

At 11:40, the duo climbed up to the "Chelyabinsk Bivouacs", and at 12:30, stones started falling on the snow — and suddenly a snowy bridge collapsed, located to the left of theirs. Until the end of the day, the duo kept looking at their bridge — worried that it would collapse too.

In the evening, a figure appears on the pass, another… then two more — these are Meshkov and Retyunsky, our third duo, who went to the tea house for additional products and gasoline. With them are observers Tatyana Retyunskaya and Sergey Sigov, a воспитанник (pupil) of the Korkino section. "Let's go down to meet them and carry their backpacks!"

The "main observers" — our release officer M. S. Levin and photographer Yura Shekhov — will come to the Central Pass tomorrow afternoon to leave after our victory. By dusk, we were all together: captain Stukhin, his deputy Retyunsky, Vakhmenin, Ivashchenko, Meshkov, and Shchukin — the entire declared starting lineup. It's good that we decided to climb this edge in six! Everything is fine, but the sky doesn't like some of us… oh, they're cursing!

July 21, 1976

What we came here for begins in the darkness. All eight people — we six and two observers — are on our feet, products and equipment are weighed and divided from the evening before, breakfast is being heated — preparations are brief. After some hesitation, Shchukin puts on a sweater (although he knows it will soon be hot).

They left the route on time. The excitement has subsided, now they need to work and not waste time. It's getting light. Yesterday's steps are clearly visible and hold well. One by one, they cross the bridge that held and climb up to the rocks. Such steep snow has not been seen this season.

Shchukin and Meshkov climb along the first perlon ropes at the end of the chain. Meshkov unscrews the ice "Uvints" and moves on, and Shchukin reaches the place where the perlon rope is attached to the first rock hook. The hook is hammered in tightly, and it's in a recess in the rock: it's inconvenient to remove it with an ice pick, and standing is also uncomfortable, so he has to hold onto the rock with his hand. Shchukin rests, then takes a break again…

— "Just leave it!" they shout to him from above.

"There are still three of them at the second perlon ropes, — Shchukin thinks, — I'll manage to remove it. The hook is good, titanium — why leave it at the start of the route?" Finally, he copes with the hook and approaches the rocks. 6:45 — and water is already flowing. Meshkov and Stukhin are wearing Vibram soles; they haven't put on their galoshes yet.

The rest changed into galoshes and went through the pink "forehead" along the perlon ropes. The rope got wet overnight, and from the very first steps, they all started getting wet. Water is dripping from above faster and faster. Shchukin enjoys removing hooks — everyone has left, and he's hanging in his harness-belay under the overhang and working.

A convenient harness, and why didn't we use such harnesses before? And in the camps, there still aren't any like this, but V. M. Abalakov showed it in 1973 in Tbilisi…

The water is no longer dripping. It's flowing in a stream, and the sleeves are wet. Shchukin climbs up the wet rope with a Prusik knot — and, deciding to save strength, goes climbing, only occasionally holding onto the rope. This doesn't slow down the others yet — the team hasn't dispersed, and you can't run: there are many "live stones". They go carefully, hoping the perlon ropes will end soon. Shchukin is already hot in his sweater, but then there's a shout from above:

— "We need hooks!"

Vakhmenin reached the upper end of the last perlon ropes hung the day before and waits. Stukhin brought the end of the lower rope third, and Ivashchenko and Vakhmenin continued working further. After 10–15 m, as Vakhmenin said, there was a platform on which they would set up a control cairn.

The authorized representative of the USSR Sports Committee, Andrey Andreyevich Smesarev, introduced them to a new catchphrase "zaturennый route" (over-turisted route), which he heard in the "Artuch" camp; we, of course, are against "turisting" our logical route, but this control cairn is NECESSARY — so that there won't be enthusiasts climbing to the first snowy saddle behind the drop directly along the pro-shooting gullies from the Eastern Pass.

While Stukhin and Retyunsky were building the cairn, it was time for radio communication — 18:00. The reception is excellent (always like this!). They report that everything is fine and that they will now drop off a piece of rope.

Shchukin climbed onto the shelf. He's smiling, but it's clear that walking along the perlon ropes is a burden for him; he wants to move forward, into the "attacking trio". The end of the perlon ropes. Above are Meshkov and Retyunsky; they're not moving, they're going.

So, they can equalize the length of the third rope. Done… it's inconvenient to throw the cut piece down — sometimes the wall gets in the way, sometimes their own rope.

— "Come to us, there's a bigger platform here!" Retyunsky advises from above, but Shchukin stubbornly swings and throws, seeing that the flying rope got caught and lay 10 m below him.

He takes off his backpack, asks Retyunsky to belay him, and climbs down to get the rope. Got it, climbed back up to his backpack, put it on, and went up to Retyunsky. Retyunsky drops the cut piece onto the glacier. From here, it shouldn't have fallen into the bergschrund — and yet, as it turned out, it did. So, one less sparrow to catch in Margebe (you have to pay with a rope…).

Shchukin takes off his sweater with pleasure — finally! — and his hooks are already given away.

Having gone another 60 m to the cairn, Vakhmenin found himself in the wettest place. Then Ivashchenko stood on the shelf by the stone — he was releasing Vakhmenin further and was shivering, and water was splashing on him from the cornice. "Snowbirds" started flying. Vakhmenin went further, snorting, but continued to whistle.

Then everyone tried to pass through this 60-meter cold shower along the perlon ropes as quickly as possible. To make matters worse, the sun hid behind a cloud, now constantly hanging over the summit. Wherever you look, high clouds stretch — it's likely that the weather won't hold tomorrow.

— "Don't torture yourself on the perlon ropes, just go forward," Retyunsky says, and now Shchukin listens, takes the free rope, and moves on. And ahead is another "ablution" (alas, not the last). Whether you like it or not, we all have to go through it. On wet, slippery rocks, you can't run even along perlon ropes; everyone will get noticeably wet, but Shchukin, who is leading, will get the most wet of all.

The rocks are nice, rough. They're wet, even slippery with lichen, there's nothing to hold onto with your hands, but there's something for your feet. Shchukin passed under the overhang along the gray wall, and at 9:00, Vakhmenin and Ivashchenko climbed up to him along the perlon ropes — and were relieved to pour water out of their galoshes. Shchukin left them his wet backpack and towel, wading through the water.

Oh, the baths here are cold — "sobering up quickly"; the only joy is that the galoshes hold here on the "throughout" steep slope, as long as there's no dirt under the sole. Having passed the rope to the end, Shchukin secured it to a hook by a snowfield on a wide shelf and hastily began to change shoes — fortunately, snow work was starting.

The wet Ivashchenko approached him and took Vakhmenin, who brought the end of the rope. Ivashchenko put on boots and went along the snow to the right edge of the couloir. The unfrosted Shchukin approached Ivashchenko, went further, to the end of the couloir.

From above, "snowbirds" flew — mainly small pieces of ice that fell into the left part of the couloir. But they were reliably sheltered by the overhanging right edge of the couloir. Here they worked in a rope team for the first time that day.

It's probably warm around — but they're shivering, their teeth are chattering, their lips aren't listening.

Then there were no rope teams as such:

- The first one went out;

- The end of the free rope was brought to him along the perlon ropes;

- The first one was released;

- The third one climbed up with the end of the third rope after the fourth, fifth, and sixth had passed along it, and so on.

At the end of the couloir, there is a wet wall, and between it and the snow — a snow-ice ridge.

Having ridden the ridge, Shchukin dives under another ice shower a couple of meters later.

"Brrr! — Shchukin thinks. — It would be better if I went without a backpack! Of course, I'll pass here even with a backpack — but without it, it's faster, less wet…" — sitting, he hammers a hook into the right wall of the couloir.

In front of Shchukin is a snowy plug, on the left of which there is a stone. Shchukin stretches on tiptoes to reach the stone — but his foot slips off the ridge, and Shchukin sits down on it with a thud a meter below. Now he doesn't care about the shower! Water flows down his body and "refreshes very much".

Shchukin reaches for the stone again, hammers in a hook, and, clinging to it, manages to climb up the top of the snowy steep slope. Another 10 m up the snow — finally, a decent goal. Shchukin hammers in a hook — and returns to remove his "artificial support" from a boulder frozen into the snow.

Those below wait patiently.

Shchukin goes up again. He's at the hook, it's getting easier, but after 10 m, the rope ends. "A little more… to the end of the drop, there are no more than 10 m left — there's our first goal: the break in the plane of the drop, the start of the direct path to the first snowy saddle.

Ivashchenko climbed up to him along the perlon ropes with the end of the rope — and tried to go further, but after 15–20 meters, he looked down sadly: "There's ice under the snow! It's slipping!" — and began to descend.

Meanwhile, Stukhin had already put on crampons and stepped onto the slope.

The technique was "mixed", as they say:

- steps are made until the crampons start to catch on the ice.

The ice became steeper, but the insurance through hooks hammered into rock outcrops was reliable. It's good because, in one place, Stukhin felt that the teeth were bending…

Maybe this wouldn't have happened, but their crampons can be expected to do anything — so they had to swing their ice axes. This warmed them better than the praised Tajik sun and left steps on the slope "for warmth".

The last to appear on the saddle was Retyunsky, who shouted:

"Lyokha! I haven't seen you all day! There's no one to smoke with, and my ears are swollen!" — and poured water out of his anorak pocket.

For the second time (the first was in the morning), they all gathered together, chewing on sausage with chocolate. The thought of abandoning the planned bivouac on the 1st snowy saddle was blasphemous — they were so wet and frozen… and yet, they couldn't afford to lose time — the weather was deteriorating before their eyes!

— "Let's move on?"

There was no need to persuade anyone. Putting on wet galoshes, they unanimously moved higher, towards the expected "perya–polki" system (as on the bastion of the northern edge of Central Zamin Karor, passed by Shchukin's group the day before). By analogy with that route, they calculated that one of the snow-covered shelves hanging above them would be suitable for a bivouac.

As it turned out, the decision to gain altitude was the only correct one, and as for a shelf for a bivouac, their premonition didn't deceive them. Vakhmenin quickly passed along rocks of medium difficulty upwards, where an overhang begins. Shchukin approached him, released him again. Under the excessively overhanging internal angle, they saw something like a shelf leading to the right and turning into a chip there. Vakhmenin and Shchukin moved in a rope team along this "half-shelf". When Stukhin approached them, a dispute was in full swing: where to go next?

— "We need to go further to the right. It's simpler there," Vakhmenin insisted. "It's too early to climb up; it's complex here." — "If we go to the right, we'll end up on the pro-shooting shelves under the gullies. You saw those gullies on the right part of the bastion yourself. But here, along the internal angle, I can pass," Shchukin persisted. — "Right, Vovochka, — let's go up! On the right, it's already snowing, and it's not worth going far from the edge," Stukhin supported Shchukin. It's beautiful to see Shchukin climb… if only there were spectators here, TV cameramen! The internal angle turns into a chimney with a plug. Shchukin bypasses the overhang on the right along the wet wall, then again uses a chimney — and on the left, a small platform is discovered. Shchukin throws a rope over a ledge, shouts: "Perlon ropes are ready!" — and looks around with displeasure, noting that the wall to the right of the platform is pro-shooting. Above Shchukin is a steep slope, and on the left of the chimney, it's unclear if it's passable. Vakhmenin climbed up to the platform above the plug along the perlon ropes, followed by Ivashchenko, who brought the end of his rope. Shchukin suggests his option for further movement. This path begins like this: standing on Ivashchenko's shoulders at the overhang, Shchukin hammers in a hook as high as possible and, holding onto the carabiner, reaches for a hold, then for the next one… At the end of the "option", Shchukin spends 15 minutes finding a semblance of cracks, blocking 3 hammered-in hooks, and ensuring the reliability of the perlon ropes. He climbed here without a backpack, and Ivashchenko followed him along the perlon ropes with a backpack. Watching him, they unanimously decided to pull up their backpacks. And so they did: while Retyunsky and Stukhin pulled up the backpacks, the Vakhmenin — Ivashchenko team passed along the scree shelf and crossed the northern edge. Having reached the end of the shelf, Ivashchenko entered the internal angle and climbed up it. Stukhin, approaching the end of the shelf, shouted:

— "Lyokha! What about a platform? It's already the fifth hour; it's time to look for one!" — "You can dance here, — Ivashchenko immediately replied. Pausing, he added: — True, only while attached."

Half an hour later, two more people climbed up to him. The "dance floor" turned out to be a flat, inclined stone. There were no amenities, except that the snow was within hand's reach, literally. Ivashchenko climbed up the wall with a slit, the slit turned into a chimney, and then Ivashchenko reported that there was a better platform above the chimney.

— "Captain, you'd better go up there yourself without a load and decide," Vakhmenin said. — "We'll take Lyokha's word for it. Why carry backpacks then?" Stukhin replied and started climbing with his backpack. The platform was indeed excellent, not sloping, and large. They chose a place for the tent under an overhang, with water nearby. They stretched perlon ropes towards the edge, and only then began to clear the platform. While they were heating water, the Vakhmenin — Ivashchenko team began to scout the path along the rocks directly up from the platform, and the Stukhin — Retyunsky team — the option of moving further left along the snow-covered shelf. The path along the snowfield up was visible; preliminary perlon rope installation was not required; in the morning, they would pass quickly. From here, the option proposed by Ivashchenko was visible — it "slightly" overhung and was clearly more complex.

For dinner, they heated up buckwheat porridge with meat, cooked earlier down below. We adopted this "duty" dish from A. G. Ryabukhin, the Chelyabinsk "Snow Leopard" chef.

They boiled tea three times, then began to settle in. Stukhin and Meshkov flatly refused to get into the tent and lay down nearby, wrapped in a polyethylene film.

Around 21:00, the radio communication with Retyunsky ended. They didn't hear what he was saying — they fell asleep… He returned, said that everything was fine, the reception was good — and immediately fell asleep.

The night passed normally. Shchukin curled up around a hard stone protruding from under the tent by the end of the night, got very comfortable, and "slept through the whole life".

Stukhin and Meshkov, tossing and turning, wrapped themselves in their self-belay loops — but still claimed to have slept better than everyone else. We got a good rest — the wake-up call was set for 7:00.

July 22, 1976

The annoying "Get up!" was shouted by Retyunsky. Breakfast — the same buckwheat porridge with meat — was heated up by Meshkov. Convenient and quick, and quite tasty. Usually, it takes us 1 hour from waking up to departure. It was the same this morning. But at 8:00, they didn't leave — Stukhin insisted on waiting until the rocks were free from ice. It's cold outside the tent, the sun is obscured. It's good that they stocked up on water the night before — the stream on the rock froze, and the rocks are shiny.

They will leave at 9:00, while drinking tea and gathering. At 8:00 in the morning, Retyunsky made contact and reported upon returning that they were worried down below, wondering if the tsetse fly had bitten them.

There were fewer products. The "attacking trio" carried them, while everyone else carried an unchanged load. The captain decided not to redistribute the load and thus ease the backpacks of the "attacking trio".

— "I wonder how much more altitude we need to gain?" Retyunsky asked, packing his backpack. — "Ask Meshkov about it. He's the one who dropped the altimeter on the grass," Stukhin replied. — "Your altimeter wouldn't have shown the correct height anyway. Something around 6000 m," Meshkov said, laughing. "And without an altimeter, it was clear that the weather wouldn't hold. It's time to leave the familiar sharp stone under the tent. At 8:45, Retyunsky and Stukhin, in a rope team, went to trample the snow. Two options were visible behind the snowfield. They argued a bit, then Retyunsky climbed up the snowfield to the right onto a ridge:

— "It's smooth further up, and the top overhangs. We need to go left!" And he descended from the ridge and began to ascend along a wide couloir with ice. Crampons weren't needed; a thin crust of snow hadn't thawed yet and held well.

The Vakhmenin — Ivashchenko team was already approaching. It turned out that the couloir led to a ridge along a narrow saddle of a not clearly expressed counterfort extending to the east from the main edge.

To the left behind the counterfort — a steep, wide gully, a kind of canyon, entirely filled with ice. It's constantly snowing there; the rocks above the gully are already lit, and the ice has turned into rivulets.

On a ledge, they put on galoshes; Ivashchenko climbed into the "forehead" along the wall of the counterfort — the right edge of the "canyon" — to a shelf under an overhang. He stopped on the shelf, pulled out his backpack. Now, along the perlon ropes, they brought the end of the second rope. They had to move left to the end of the shelf.

Vakhmenin climbed up, then Shchukin. Shchukin, on these and subsequent perlon ropes, was convinced that on a wet rope,