Ascent Passport

- Ascent class — technical

- Ascent area — Alay range — 5.1

- Peak, its height, route — Main Sauk-Dzhaylyau via Central peak with ascent to Central peak via northern wall.

- Estimated difficulty category — 6th cat. diff.

- Route characteristics:

Height difference:

- to Central peak — 1505 m

- to Main peak — 198 m Total height difference of wall section — 1703 m Steepness:

- to Central peak: ice part — 56°, rock part — 81°

- to Main peak overall steepness — 79.5°

- Route length: 2603 m, including: wall — 1983 m, ridge — 620 m

- Section lengths: I cat. diff. — absent, II cat. diff. — absent, III cat. diff. — 300 m, IV cat. diff. — 570 m, V cat. diff. — 1128 m, VI cat. diff. — 605 m

- Pitons driven:

- rock (and chocks) — 286, including 12 for creating artificial anchors

- ice — 82, including 11 for creating artificial anchors

- bolt — 13

- Total climbing hours — 82.5 hours

- Number of nights on the route, their characteristics: 6 nights (I — in bergschrund in tent, II and III — on ledges — 3 people in hammocks, 5 people sitting, IV — on ledge — 5 people sitting under tent, 2 people lying on ledge, 1 person in hammock, V — sitting on ledge, VI — in tent on ridge).

- Name of team leader, participants, their sports qualification:

- Kovtun Vasily Grigoryevich MS — team leader

- Bodnik Vitaly Nikolayevich MS — deputy leader

- Balinsky Anatoly Pavlovich MS — participant

- Bolizhevsky Valery Konstantinovich MS

- Verba Alexander Andreyevich MS

- Fomin Alexander Sergeyevich MS

- Vabitsky Alexander Vladimirovich CMS

- Ovcharenko Valery Davydovich CMS

- Team coach: Kovtun Vasily Grigoryevich.

- Date of departure and return: from August 4 to August 12, 1978.

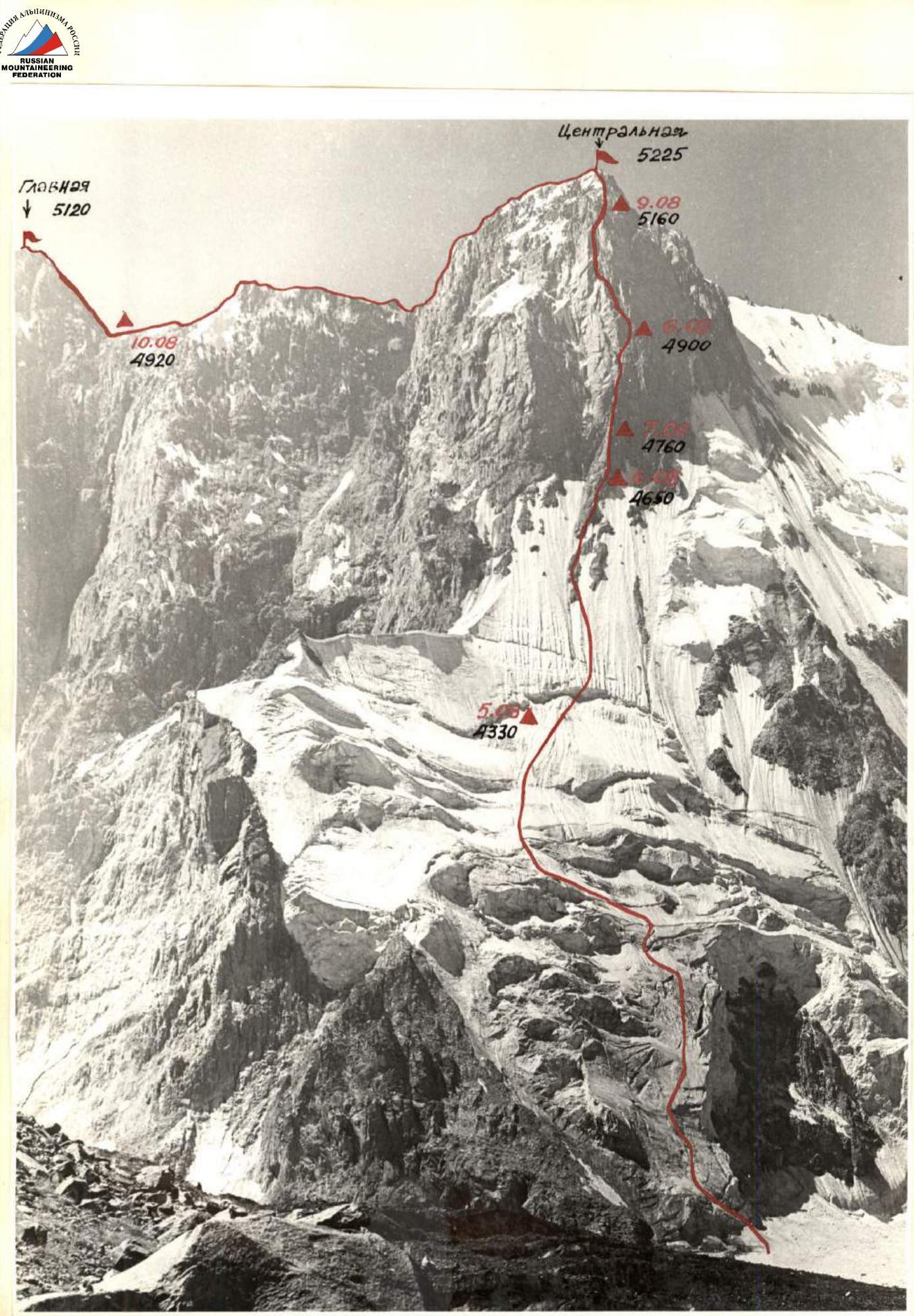

Technical photography of the route

Photo #4 3800 June 1984. Lens type — Industar 50, focal length 52. Shooting point #1, distance to object 3 km. Δ — nights and their heights, ○ — main landmarks.

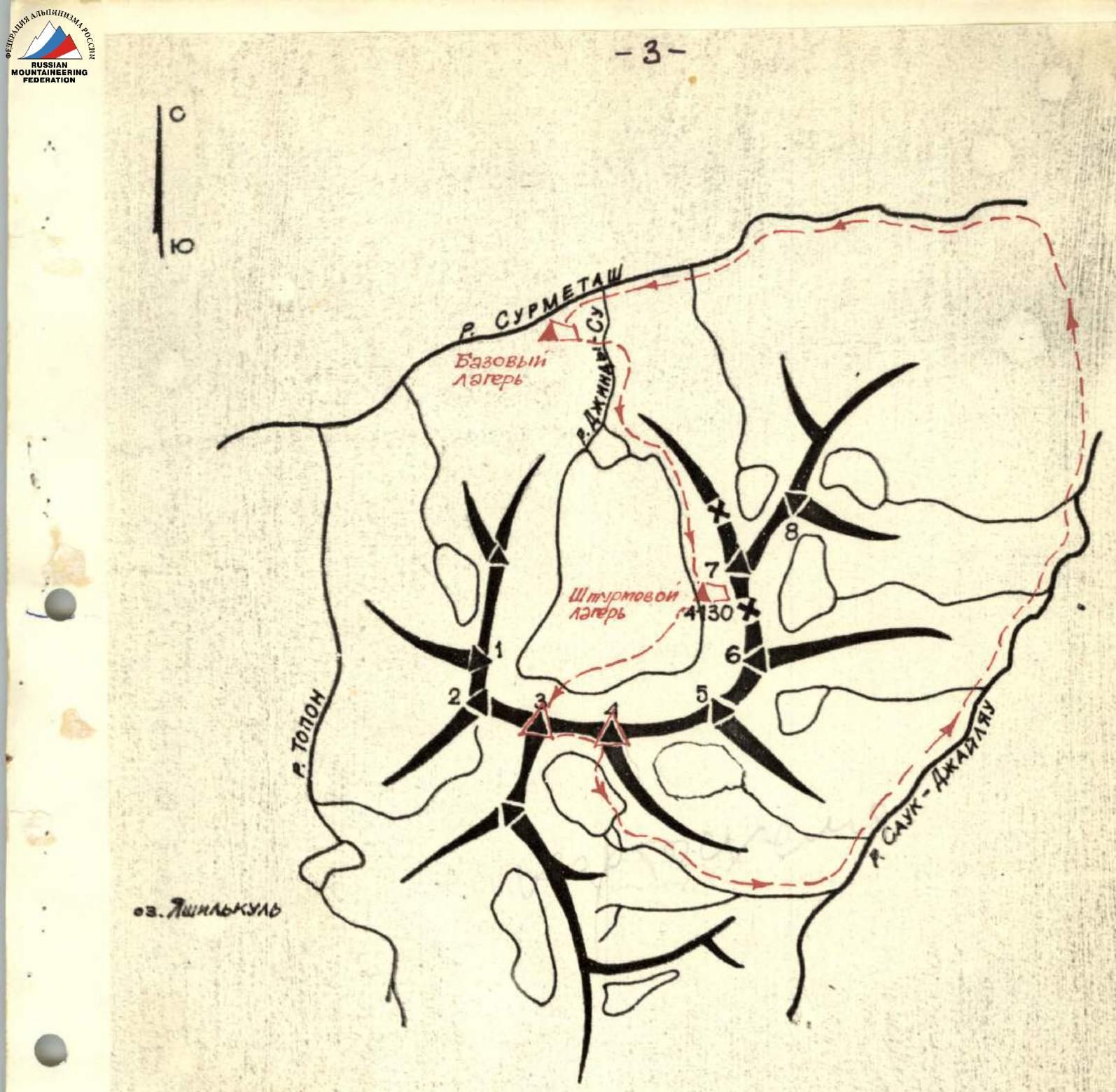

Ascent route profile

Brief geographical description and sports characteristic of the area

The Sauk-Dzhaylyau peak massif is located in the northern spur of the Alay range. The massif is almost 1 km higher than the range. The cirque formed by the Sauk-Dzhaylyau massif is horseshoe-shaped, open to the north. There is significant glaciation inside the cirque. The glacier area is about 5 km².

The Dzhindy-su river flows from the glacier, which flows through a deep canyon into the Surmetash valley and flows into the river of the same name. The Dzhindy-su river is quite full-flowing, and its crossing is challenging, especially in the second half of the day.

In the southern part of the horseshoe, there are three large peaks:

- Central Sauk-Dzhaylyau — 5225 m,

- Main peak — 5120 m (by altimeter),

- First Western peak.

In the southeastern part of the massif, the following can be distinguished:

- Snowy Sauk-Dzhaylyau — 4800 m,

- Southeast peak — 4730 m,

- Eastern peak — 4960 m.

The ridge of the massif nowhere drops below 4600 m. Only between the Southeast and Eastern peaks is there a saddle with a height of about 4150 m. The massif breaks off into the cirque with walls. Steep, destroyed ridges extend from the horseshoe.

All routes to the Sauk-Dzhaylyau massif peaks from the north are very challenging and mostly combined.

In our opinion, all routes on the Sauk-Dzhaylyau massif are better climbed in spring or early summer when the walls are still covered with ice and snow.

The Central and Main peaks of the massif face the cirque with grandiose walls. In our opinion, these routes are of the highest category of difficulty. The Leningraders (1977) who first described the Sauk-Dzhaylyau massif in sports terms shared the same opinion. The rocks of the Central and Main peaks are composed of granites, granodiorites, with a predominant angle of inclination of rock slabs and wall microrelief of about 80°. The lower part of the route to the Central peak is steep ice. On this section, the steepness is about 50° in the lower part and more than 60° in the upper part. Especially this year, when there was no snow on the ice at all, the lower part of the route presented significant difficulties.

- Sauk Western I Tower

- Sauk Western II Tower

- Sauk Central — 5225 m

- Sauk Main — 5120 m

- Sauk White/Snowy — 4800 m

- Sauk Southeast — 4730 m

- Sauk Eastern — 4960 m

- Sauk Dvuzubka

The lower part of the rock section of the route is heavily destroyed; the middle part is monolithic, smoothed with few cracks and underdeveloped microrelief, with smooth ledges, many sections are climbed on friction. The upper part is more fragmented. There are good cracks for protection. The cracks are mainly vertically developed. The granite has a pinkish hue.

WEATHER CONDITIONS. The weather in July-August 1978 was generally characterized as good. It should be noted that there is a microclimate in the Sauk-Dzhaylyau massif area, likely due to:

- the significant elevation of the massif above the surrounding peaks;

- quite extensive glaciation.

In the cirque, cloudiness often appears in the second half of the day. However, throughout the summer of 1978, there was practically no precipitation. This led to the fact that this year all the snow in the cirque melted, and ice was exposed everywhere. For this reason, the rockfall danger on the routes increased significantly, and some routes became practically impassable. "Rock avalanches" could be observed on the walls of the Central and Main peaks literally "rockfall". Passing any route on these peaks requires:

- great attention;

- correct tactical planning of the ascent;

- great care when working on the route.

The REMoteness FROM SETTLED AREAS AND ALPINE BASES also created certain difficulties in organizing and conducting the ascent. The nearest settlement, Karaul, is 60 km away from where the expedition's base camp was located. The very poor road (still passable by car) ends 5 hours' walk from the base camp.

It was here that all expedition participants were delivered. Further cargo transportation involved all participants using horses. In about a day, through a pass, one can reach the "Dugoba" alpine camp.

The first ascenders on the Sauk-Dzhaylyau massif were Uzbek climbers, who in 1977, as part of the USSR Championship, ascended the Central peak. Their route passed somewhere near the bastion, which our team also followed. In the lower part of the bastion, we found pitons and retrieved a note left by the first ascenders. However, we did not find any further traces. Apparently, the route taken by the Uzbek climbers was to the right of ours.

The ascent of the Uzbek climbers ended tragically. Our team dedicates its ascent to their memory — the memory of the first ascenders on the Sauk-Dzhaylyau massif.

Organizational and tactical ascent plan

The combined team of the Ukrsoviet "Burevestnik" began preparations for the 1978 USSR Championship in the autumn of 1977 when all participants in the planned ascent were gathered in Kiev. Here, the object of the ascent was finally clarified and chosen — the Sauk-Dzhaylyau peak.

To this end, all available materials regarding ascents to the Sauk-Dzhaylyau massif, available in the Alpinism Federation and the USSR Sports Committee, were studied. Literature on:

- the geological structure of the Alay range;

- its nature;

- glaciation; was also studied, as well as routes and structures of nearby peaks.

To photograph the objects of the ascent, in 1977, one of the future ascent participants, Balinsky A.P., climbed to the Sauk-Dzhaylyau massif area. After studying his photographs, the final decision to ascend Sauk-Dzhaylyau was made.

PREPARATION BEFORE DEPARTING TO THE MOUNTAINS. All participants directly prepared for the ascent during the autumn-winter period of 1977–1978. All participants conducted training in their sections according to a plan developed by the team coach. Training was conducted no less than four times a week, and starting from February 1978, additional training on rock formations was added on Saturdays and Sundays. Here, the following were practiced:

- techniques for passing high-complexity sections;

- tactical and organizational issues of team work.

In May 1978, the team conducted a 15-day gathering in Sudak, where rock formations were used to finalize:

- tactical and technical interaction of rope teams;

- leader changes;

- rope hauling;

- organization of bivouacs on walls.

The equipment used by the team was checked and tested here (with acts drawn up). During the autumn-winter period, the planned amount of titanium rock and ice equipment was manufactured. The team used titanium carabiners produced in Moscow. All equipment showed full suitability for passing high-category routes.

Further preparation was conducted at the participants' places of residence according to individual preparation plans.

II. PREPARATION IN THE MOUNTAINS. On June 12, all participants in the future ascent arrived in the mountains. Six people were in the Petra I range area, and two people were at the "Artuch" alpine camp. Cycles of ice-snow and rock training were conducted, and training ascents were made.

Then:

- Participants in the Petra I range made a first ascent of 5B difficulty category.

- Participants at the "Artuch" alpine camp made an ascent of 5B category, and then a first passage of 5B difficulty category.

On July 14, all 20 climbers of the Ukrsoviet "Burevestnik" expedition gathered in Fergana. A container was received, and all logistical issues were resolved. On July 16, 1978, the team departed for the ascent object.

It was decided to organize a base camp in the "Topolinaya roshcha" in the Surmetash valley. This is approximately 5 hours from the unloading point. Cargo transportation was carried out using pack animals and participants. On July 17, the expedition's base camp was deployed and equipped.

In the base camp, there was a "Nedra" radio station, which maintained communication with the KSP of the Pamir-Alay region. For communication between the base and assault camps, "Nedra" radio stations were established. For communication between groups and with observers, "Vitalka" stations were used.

The expedition included two doctors and a wide range of medications.

The first reconnaissance sortie under the Sauk-Dzhaylyau massif showed that the most rational path to ascend to the cirque goes along the right (orographic) side of the river. This does not require hanging several hundred meters of ropes, as the Leningraders did in 1977. A bridge was built to cross to the right bank, and there were no technical problems further to the assault camp.

The assault camp was organized on the glacier moraine, 30 minutes from the start of the route. Three tents were set up, and all necessary supplies and equipment for the ascent and observation were brought in. A 40x spotting scope installed in the assault camp allowed for qualitative examination of the planned route sections.

As a result of prolonged observation of the Sauk-Dzhaylyau massif, it became clear that the only safe path to the Sauk-Dzhaylyau peak is via the Central peak's Northern wall and then along the ridge to the Main peak. All other paths are very rockfall-prone. Especially in the 1978 season, when rockfall danger in the Alay range was heightened due to extremely dry weather. "Rock avalanches" could be observed on the walls of the Main and Central peaks, covering the entire wall. There are no safe ascent paths here. Only the bastion of the northern wall provided a possibility for ascending the peak. In the couloirs to the left and right of the bastion, there was also continuous rumbling. Even the bastion itself required great care and attention when passing, especially in its lower part.

When passing the ridge from the Central peak to the Main peak, we had the opportunity to see the walls on the Main and Central peaks. The walls are no less complex than the bastion we passed but are very dangerous. Visible ledges are covered with countless stones ready to slide down at the slightest gust of wind. In our opinion, these walls are very dangerous. Their passage should apparently be done:

- early in spring;

- late in autumn;

- in a cold year; possibly making the walls safer. Additionally, there is a possibility of encountering destroyed rock belts on the walls, where organizing protection would be practically impossible. Such a belt is visible on the Main peak and is quite extensive.

The team's departure to the route was scheduled for July 29. However, accidents in the area did not allow for departure on the scheduled dates, and only on August 4 was permission granted by the authorized representative of the USSR Sports Committee to proceed to the route.

On August 4, a team of 8 people departed from the base camp.

The gathering plan provided that throughout the team's work, it would be backed up by a group of at least 6 people — Candidates for Master of Sports. Additionally:

- observers were constantly positioned under the wall, noting the team's movement path from a photograph;

- radio communication was maintained with the group and the base camp;

- observers monitored the group through a 40x telescope.

The TACTICAL ASCENT PLAN adopted by the team was dictated by the complex relief to be overcome, the danger of rockfall, and the possibility of ice falls on the route.

During work on the route, all team members always used a double rope. The first climber passed the section on separate ropes, and the second climber, upon reaching the first, pulled up double ropes. Ropes were fixed on at least two pitons — each rope separately — after which the first rope team could continue.

The first climber always worked without a backpack. Warm clothing and pitons were with the second climber and could be easily passed forward with a "connecting" cord freely running from the first to the belayer.

Throughout the wall section of the route, the first climbers wore galoshes. The rest of the participants wore Vibram shoes.

The team's work was planned so that the maximum possible part of the route was passed or processed at all times. This allowed the entire team to start work daily practically simultaneously, significantly reducing the ascent time. We aimed to pass the given route in the maximum short time with, naturally, maximum safety.

The ascent plan was as follows:

- On the first day of the ascent, we planned to cover a significant part of the ice and hide from possible rockfalls in the bergschrund in the morning.

- On the second day, we planned to exit onto the bastion's rocks and have a night's rest on a well-examined ledge on the bastion.

- On the third day, we planned to pass a very complex smoothed section of the bastion and have a night's rest on a ledge after passing this section.

On the fourth day, we planned further movement along the bastion. A large internal corner transitioning into a chimney was visible through the telescope. We planned to have a night's rest on a small ledge.

On the fifth day — passing the wall and exiting under the peak. We planned to have a night's rest on a rock outcrop under the peak.

On the sixth day — we planned to reach the Central peak and traverse the ridge to the Main peak. We planned to have a night's rest on the ridge.

On the seventh day — we planned to ascend the Main peak and begin descent from the peak.

On the eighth day — we planned to descend to the base camp.

It is worth noting that prolonged observation and a realistic assessment of the difficulties expected on the route allowed for the creation of a plan that was executed precisely. The team passed the route according to the planned schedule.

NUTRITION. The daily ration consisted of high-calorie products and weighed about 700 g per person per day.

In the morning:

- tea;

- honey;

- glucose;

- meat;

- black caviar;

- sugar.

In the evening, soup and tea were cooked. During the day, participants ate from a "daily bag". The bag contained:

- sausage;

- nuts;

- sugar;

- candies;

- glucose;

- dried fruits.

"Bags" were distributed in the morning, on the eve of departure.

The team's diet included high-calorie protein supplements. As the ascent showed, the selection of products and daily ration was compiled correctly and fully satisfied the needs of the climbers.

Ascent description

August 4

On the eve, August 3, 1978, permission was obtained from the authorized representative of the USSR Sports Committee and the head of the KSP of the Pamir-Alay region to proceed to the route for the ascent. At 7:00, the team of 8 people and two observers departed from the base camp to the assault camp.

At 11:00, everyone arrived at the assault camp. Backpacks and equipment were prepared. Departure was scheduled for 00:00 on August 5. We went to bed at 18:00.

August 5

We depart at midnight as planned. Ahead is a difficult and "cold" day. According to the plan, we must cover a significant part of the ice section of the route. The path was examined during observations. Headlamps allow us to quickly cross the moraine and glacier and approach the start of the route. We ascend the steep avalanche cone (section R0–R1) to the bergschrund. The bergschrund is heavily torn, and the upper wall of the bergschrund towers over the lower by 15 meters. The ice wall has a steepness of at least 85°. Practically sheer. Everyone works in crampons. The section is passed using ladders. Titanium pitons allow us to quickly overcome this section (R1–R2). Then we exit onto steep ice fields. We climb an ice pitch of 3 ropes (180 m) (section R2–R3). Protection is through screw ice pitons. Further, the steepness increases to about 60°. We climb 120 m of slope, avoiding crevasses (section R3–R4). Then, up and to the left along the slope, which has become less steep, we climb 80 m (section R4–R5). The slope then becomes steeper again (about 45°) and we climb about 40 m along it (section R5–R6), avoiding crevasses. Further, up and to the right along the slope, we climb 100 m (section R6–R7). The slope steepness increases. We climb another 50 m on ice covered with a thin layer of snow (section R7–R8). Then we climb about one and a half ropes along the ice slope with snow and approach the bergschrund (section R7–R8). The bergschrund is torn and deep, crossing the entire slope.

To the left of our planned path, a large plug is visible in the bergschrund. We decide to go there and organize a day's rest and night's stay.

We move along the edge of the bergschrund for about 60 m and settle on a good plug. From above, we are protected by a large ice overhang. After examining it, we are convinced of its strength. We set up a tent. Stones and ice chunks are already falling down the gully. However, we are safe.

The day passes calmly. At 18:00, when the sun no longer illuminates the slope so intensely, we start processing. We cross the bergschrund along the wall. There are no bridges anywhere. The wall is about 15 m high, absolutely sheer (section R9–R10). We use screw pitons and ladders.

Beyond the bergschrund, we move slightly to the right, away from the central gully. We cross the gully along the lower edge of the bergschrund. The slope has a steepness of about 60° and a length of about 40 m (section R10–R11). It leads to the next bergschrund (section R11–R12). The height difference between the edges is small, about 3 m, but the upper part of the wall overhangs. We pass the section using ladders. Having overcome the bergschrund, we exit onto a steep ice slope. Its steepness is about 65°. The ice is covered with a thin layer of frozen firn. There are exactly 2 ropes of such ice to the first rock outcrops (section R12–R13). During the day, when this section is illuminated by the sun, it reflects rays like a mirror. Now, passing this "mirror" requires great effort. Twelve-tooth Austrian crampons (from "Stubai") are very helpful.

After processing, the trio descended to the tent. Dinner. The plan for this day is fully executed. We spend the night sitting in the tent. It's cramped, but at least it's warm.

August 6

The night in the bergschrund seems very long. We want to move on as quickly as possible. We depart at 5:30 in the morning. We pass the ropes processed the day before. We quickly approach the rocks. However, the rocks are not very welcoming. The rock outcrops are absolutely destroyed, tile-like formations. It's extremely difficult to drive pitons into them. However, their steepness is significant. It's even surprising how they stand, these rocks.

We climb about 60 m along these rocks, alternating with ice sections. We move very cautiously; the rocks are heavily destroyed (section R13–R14). As we move up, the rocks become stronger. The steepness is about 70°. About one rope of such rocks and an ice section after them (section R14–R15) lead us to smooth slabs with few holds. The slabs are steep, and this section is about 50 m long (section R15–R16). Overcoming the slabs requires significant effort and caution. There are large "live" slabs. The slabs turn into an absolutely sheer wall, about 60 m long (section R16–R17). Unlike the slabs, there are cracks and some relief here. Climbing is complex. There are tile-like rocks that easily break off from the main mass. Further, the steepness of the rocks decreases slightly, and we climb about 50 m along a section of reddish granite (section R17–R18). There are two small overhangs on this section. At the top, a ledge is already visible, which we plan to reach and where we plan to spend the night. However, there are still more than 50 m of sheer, smoothed wall to go (section R18–R19). Climbing is very challenging. In many places, we have to climb on friction.

The ledge was a small platform, and after significant "construction" work, it became about 1.5×2 m. While making the ledge suitable for the night, hanging hammocks, and preparing food, three people continued further processing of the route. Eventually, we equipped a platform where 5 people could sit, and three people spent the night in hammocks. We left the 1st control cairn here.

August 7

We wake up early. It's not warm in the hammocks. At 7:30, we depart and start passing the sections processed the day before. It's clear that with backpacks, sections R17–R19 are impassable. We prepare loads for hauling. A trio goes up to further process the route and, while two hauls are being conducted, passes the route further.

The further path goes along the left side of the chimney. Here, we can climb, despite the route's significant steepness (section R19–R20). The rocks are smoothed. The entire chimney is crossed by an overhang, but it's smaller on the right side, so we move to the right side of the chimney. We pass the overhang (section R20–R21). Climbing is very complex. The rocks are smoothed and without cracks. We have to drive a bolt piton to ensure protection. We continue moving along the right side of the chimney. The rocks overhang and are just as monolithic. Another bolt piton is driven for protection. We pass the overhang (section R21–R22) and exit onto a smooth wall. The steepness here has decreased to about 85°. We climb 20 m of such a wall (section R22–R23). The rocks are smoothed with few holds. We climb on friction. At the end of the wall, we prepare a place for hauling. The wall leads to a large internal corner filled with ice. The ice layer is significant, but attempts to drive or screw a piton into it were unsuccessful. The ice flakes off in large pieces. The walls of the internal corner are smooth, like polished. Therefore, two more bolt pitons are driven to ensure reliable protection when passing this section (section R23–R24).

With difficulty, we find small cracks in the upper part of the internal corner for petal pitons. The internal corner ends with a plug (section R24–R25). We use ladders. Having overcome the plug, we exit onto smooth, smoothed rocks. A very complex, sheer section, although not long (section R25–R26). The wall leads to fragmented, slab-like rocks with a steepness of about 80°. Here, it's easy to organize protection. There are many cracks, mainly vertical (section R26–R27). Having secured the ropes reliably, we descend. By the time we descend, the rest of the participants:

- have passed the sections processed the day before;

- have hauled loads;

- have prepared a night's bivouac on a small ledge.

Again, three people have to hang in hammocks, and five sit practically on top of each other. But there are no more convenient places. The weather is fine, and so far, everything is going according to plan.

August 8

We depart after breakfast and receiving "daily rations" at 8:00. We start moving along the processed sections. When passing sections R19–R27, we have to conduct two hauls.

Further movement goes along the smooth walls of the internal corner. The rocks are steep and monolithic. Holds are very small. Feet are only on friction (section R27–R28). Gradually, we move to the right part of the internal corner and continue moving along its right side. Here, the steepness is slightly less, but the rocks are just as smoothed (section R28–R29).

Having climbed about twenty meters, we approach overhangs. This forces us to move again to the right side of the internal corner, and further movement goes along the steep, smooth rocks of the right side of the internal corner (section R29–R30).

The internal corner ends with huge overhangs. Therefore, we examine the path to the left. A small ledge leads here (section R30–R31).

The ledge leads to the throat of a huge internal corner. To cross the throat and exit onto the wall of the left side of this internal corner, we have to pass a small overhanging section (section R31–R32). We have to use ladders.

The rocks are monolithic. There are no cracks. We secure ourselves with a bolt piton. We exit onto strong, partly slab-like rocks (section R32–R33). Climbing is very complex but pleasant — monolithic rocks, there are cracks for pitons. Despite the sheer nature, the section is passed fairly quickly. We secure the ropes and descend to the bivouac site.

We organized a bivouac meters below section R27–R28 on a small ledge. There were no other places for a bivouac on the wall. Here:

- five people sat on the ledge, sheltered by a tent;

- two slept on a decent, albeit sloping, ledge;

- one person had to hang in a hammock.

There is no water, and we had to go for ice, traversing sheer sections of the wall. Here is the control cairn.

August 9

We depart at 8:30. The sun-warmed rocks quickly heat up. We pass the processed part of the route. On the wall (section R32–R33), we have to conduct a haul.

The wall ends with huge cornices, which, despite significant overhangs, are not strong. To avoid them, we have to traverse right along very complex, destroyed relief. A psychologically challenging place (section R33–R34).

Further, we pass destroyed, steep slab-like rocks (section R34–R35). We exit onto a very destroyed, steep wall. We can encounter large slab-like blocks. Careless movement can cause them to fall. We move extremely cautiously (section R35–R36).

The wall again ends with destroyed overhangs, which we bypass on the right (section R36–R37). The further path goes along strongly fragmented, steep rocks. There are many cracks. Almost any pitons and wedges from our "arsenal" can be used (section R37–R38).

We exit onto a decent ledge. It's already evening, and we stop for the night. The night's bivouac is sitting, as there's not enough space for everyone to lie down, but it's still much more comfortable than everything that came before.

August 10

We depart at 9:00. It's chilly. Obviously, the height is taking its toll. The morning is windy and foggy. Dark clouds are gathering from the Pamir side. Today, according to the plan, we should reach the Central peak, and bad weather is not in our favor.

We continue moving along the steep, destroyed wall (section R38–R39). Despite the significant steepness, it's easy to climb. The extensive relief allows us to move quickly and reliably. The upper part of the wall is a strong monolith. Steep slab-like rocks with few holds present significant technical difficulties (section R39–R40).

In many places, we have to climb on friction. The slabs lead to a steep ridge, which leads to the peak. The ridge is heavily destroyed and drops steeply on both sides (section R40–R41).

At 14:20, we reached the Central peak. The weather is deteriorating. Dark, thunderstorm clouds are racing directly above us. Strong wind.

We quickly write a note and leave the Central peak towards the Main peak along the ridge. The ridge is heavily destroyed, rocky. We pass three ropes (section R41–R42) of the ridge and unexpectedly approach a sheer wall. We set up a rappel down the wall (section R42–R43) and exit onto a wide, scree slope with ledges (section R43–R44). There are many loose stones on the ledges. The slope abuts a ridge. The ridge is almost horizontal but sharp. It drops steeply on both sides. On the ridge, we bypass boulders, descend, and climb back up into a gap and along a not very challenging, scree ridge (section R44–R50) approach the base of the wall on the Main peak. The wall on the Main peak starts steep and with complex relief right from the ridge.

Slab-like rocks, smoothed and steep (section R50–R51), are climbed in many places on friction.

The same smoothed rocks are in the internal corner (section R51–R52). The steepness of these rocks is about 70°. The internal corner ends with a smooth, sheer wall (section R52–R53). Climbing the wall is very complex.

Profile of the ascent route (Sauk-Dzhaylyau Main)

We secure a rope and rappel down to the saddle. For the first time in many days of climbing, there's a tent. Six people lie in the tent, and two, wrapped in cloaks and plastic, spend the night nearby. Despite bad weather (snow and strong wind), the night passes calmly.

August 11

Towards morning, it became very cold. The weather is fine again. There's not a cloud in the sky. It's hard to believe that it was snowing recently. At 7:00, without backpacks, we depart to continue the ascent. We quickly and easily pass the processed section and move further along the internal corner. The rocks are destroyed and not strong (section R56–R57).

The internal corner ends at a wall where the rocks are black. The rocks are smooth with very underdeveloped relief. Climbing is very complex (section R57–R58). The wall leads to a destroyed wall (section R58–R59), which turns into a ridge (section R59–R60), leading to the peak. The team reached the Main peak at 11:30.

To our great surprise, we find a cairn and a note on the peak. It turns out that in 1977, during the search for Tkachenko's group, Uzbek climbers ascended here from the southeast. Unfortunately, there is no information about this ascent in the USSR Sports Committee, and we, ascending the Main peak, hoped to be the first ascenders. Alas, the first ascent did not happen.

We begin descent along the ascent path to the saddle. On the saddle, we dismantle the bivouac, inform observers that we are starting descent to the southwest along an ice couloir, and allow them to descend. There's no connection from behind the ridge anyway. Along the ice slope:

- we fixed 7 sports ropes, 60 m each.

Further:

- we exited onto scree ledges;

- traversing right along the way, we reached a safe scree couloir;

- we descended the couloir to the glacier.

Then, along the glacier and moraine, we descended to vast grassy slopes. We spent the night here.

August 12

We departed at 6:00. We need to hurry to the camp. Cars are waiting for us to depart on August 13. At 17:00, the team arrived at the camp in full.

Evaluation of the ascent route and team actions

Passing any route on the Sauk-Dzhaylyau massif requires climbers to have high technical and tactical proficiency, high moral and physical preparation. Especially in the 1978 season, when, under conditions of increased rockfall danger, the team fully climbed such a beautiful and complex route.

Properly conducted pre-season preparation, a gathering to improve rock technique in Crimea in May 1978, sufficient preparation directly in the mountains allowed the team to be in the best shape by the time they started the route.

Reconnaissance and photography of the route in 1977, organization of a comfortable base and assault camp, passage of 5B category routes by all participants before the USSR Championship, availability of necessary communication means, medical care, food, and quality equipment indicate a correct and serious approach of all ascent participants to solving such a serious sports task as ascending Sauk-Dzhaylyau peak.

The team conducted a thorough study of the Sauk-Dzhaylyau massif, compiled graphs of wall illumination, rockfall and icefall graphs, and a thorough study of all possible descent paths. Only after that, weighing all aspects and features caused by the dry climate of this season, was the ascent route chosen.

The main requirement when choosing the route was:

- high technical complexity;

- ensuring maximum safety.

Pure change of leaders, sufficient supply of ropes on the route, and other equipment allowed