Report

on the ascent of Khan-Tengri peak via the southwest edge (MARBLE EDGE) by the team of CS DSO "Trud" led by Master of Sports B. Romanov

from August 4 to 11, 1964

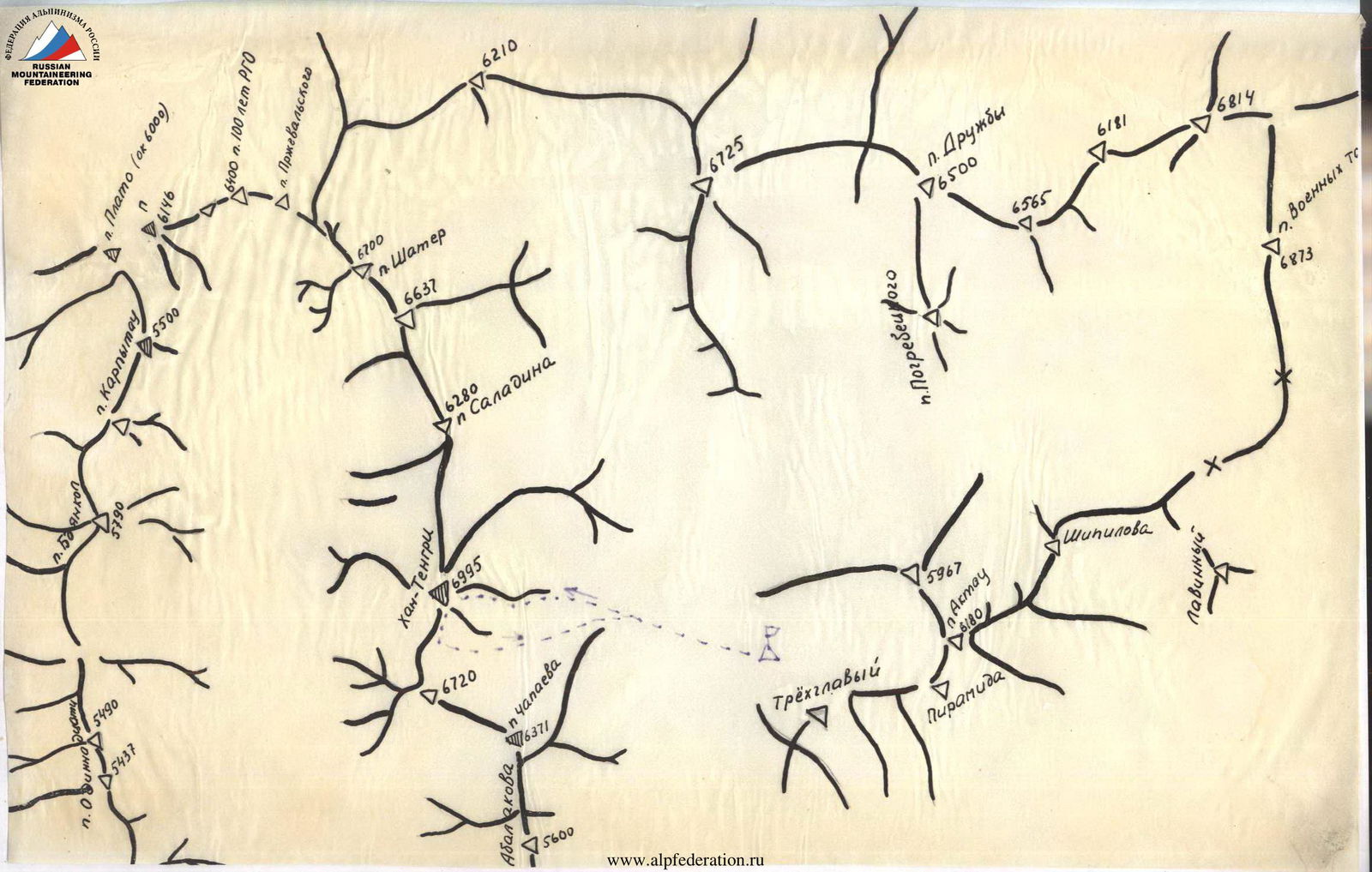

Khan-Tengri peak (6995 m) is located in the highest part of the Central Tien Shan, in an area where the highest peaks of this mountain system are concentrated:

- the Pobeda massif with the highest point 7439 m;

- Peak Voennykh Topografov — 6873 m;

- Peak Druzhby — 6800 m;

- Peak Shater with the highest point 6650 m;

and a number of other peaks exceeding 6000 m in height.

The mountain ranges in this area are stretched in the latitudinal direction, and only one ridge — Meridionalny — has a meridional direction. In the area of the central Tien Shan, the Meridionalny ridge is adjacent to the ridges stretched in the latitudinal direction:

- Kok-Shaal-Tau ridge;

- Barierny or Tengri-Tag;

- Sarydzhavsky ridge.

The northern branch of the glacier is bounded by the Sarydzhavsky ridge, Barierny, and Meridionalny, the southern branch and one of its most powerful tributaries — the "Zvezdochka" glacier — by the Barierny, Kok-Shaal-Tau, and Meridionalny ridges. The Barierny ridge or Tengri-Tag separates the valleys of the glaciers of the northern and southern Inylchek, which then merge at the beginning of this ridge in the west behind the Brodyaga peak.

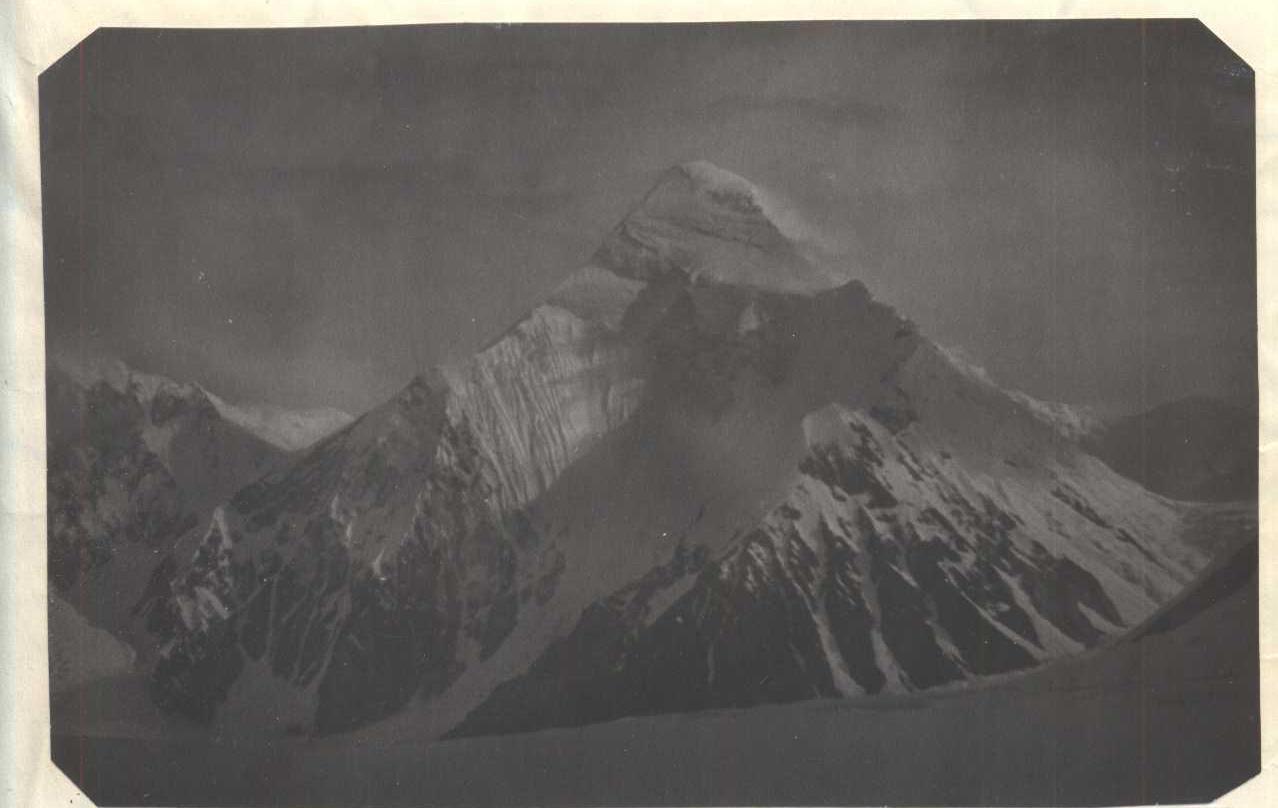

In the eastern part of this ridge, approximately 10–15 km from the junction of the Barierny ridge with the Meridionalny, there is a white marble, towering above all the surrounding peaks, the Khan-Tengri pyramid — "striking in beauty, perfection, and architectural lightness of its forms".

Khan-Tengri peak is connected to the west by a ridge with Peak Chapayeva, to the east it branches off to the not very pronounced peak of Peak Saladina and further to the Shater massif. The height of the saddles between these peaks is about 6000 m, from which steep, almost kilometer-long rock edges rise to the peak.

The peak itself is composed mainly of Carboniferous limestones of varying degrees of metamorphism. At the base, there are weaker ones (low degree of metamorphism) with veins of shale; further up towards the peak, the strength increases.

The "Marble edges" (southwestern) are composed of metamorphosed limestones from light yellow to pink in color.

The summit part:

- The pre-summit tower and the summit are composed of darker and softer limestone.

The beauty of the peak, the regularity of its forms, and its significant elevation above the surrounding peaks have long attracted the attention of Tien Shan researchers. For a long time, geographers considered it the highest point of the Central Tien Shan. For the first time, this peak was described by the famous Russian geographer P.P. Semenov, who penetrated the depths of this mountain system in 1856–1857. I.S. IGNATIEV and M.G. MERUBAKH devoted their lives to the study of the Central Tien Shan region.

The first climber to reach the foot of Khan-Tengri peak was M.T. Pogrebetsky. Starting from 1929, over the course of 3 years, M.T. Pogrebetsky organized expeditions to the area of Khan-Tengri peak. His first expeditions were devoted to the reconnaissance of the area and the study of approaches to it; a route for the ascent was planned. In September 1931, M.T. Pogrebetsky, along with two companions, reached the summit of Khan-Tengri via the western ridge. This was the first Soviet high-altitude ascent. The victory over the first "seven-thousander" was very difficult. M.T. Pogrebetsky wrote about the last meters on the way to the summit in his book "Three years of struggle for Khan-Tengri" as follows:

"Step and rest. Another step — and another rest. To the summit, no more than 100 m, we already feel it, and our legs can barely move... we walk, heads bowed, supporting ourselves with hands on bent knees... the heart pounds like a motor, and frequent rest doesn't help... A few more efforts, a few more steps... The summit".

At the same time, Sukhodomsky, along with a group of climbers, attempted to storm Khan-Tengri peak from the north but was forced to return from 6000 m due to the avalanche danger of the slopes.

On August 24, 1936, E.M. Kolokolnikov, Kibardin, and Tyutyunnikov reached the summit of Khan-Tengri, and on September 5, a group of Moscow climbers led by E. Abalakov also reached the summit. The second group finished the route with significant losses:

- On the descent, Saladina and Adadimov, and later V. Abalakov, suffered frostbite on their limbs;

- G. Gutman, who fell and lost consciousness, had to be transported;

- On September 14, 1936, Saladina died due to severe frostbite.

Thus ended the 1936 expedition.

In 1954, a group of Alma-Ata climbers led by V. Shepilov reached the summit of Khan-Tengri on September 8. They ascended "on the move" — without prior acclimatization or cacheing supplies. They were very lucky as the weather was good during the ascent. Five out of eight climbers reached the summit.

The last ascent was made by Kazakh climbers in 1962 under the leadership of Ratsek. Out of 20 climbers, only four reached the summit.

All ascents made to date have followed the same route — along the western ridge (the route of the first ascenders). The path goes from the South Inylchek glacier along its tributary to the saddle between Peak Chapayeva and Khan-Tengri (5900 m). From there, the path goes slightly to the right of the northwest edge of Khan-Tengri towards its summit.

Thus, over the 33 years since the first ascent, only 20 people in five sports groups have reached the summit of Khan-Tengri. All ascents were made along the "usual" path.

Conditions and Features of the Ascent in the Khan-Tengri Area

The Central Tien Shan region is rightfully considered one of the most interesting and at the same time one of the most serious mountaineering regions in our country. Characteristic features of this region include:

- remoteness from populated areas;

- inaccessibility.

The nearest settlement — Kui-Lyu — is about 150 km away, with about 60 km of that distance being on the glacier. The valley of the Ilychek River is cut through by gullies and ravines, making the path along the valley of the Sarydzhaz River and then through the Tyuz pass to the Ilychek River valley the most convenient for approaching with a caravan. Moving with a caravan along the glacier is quite complex and tiring, which is why the area remains little explored by climbers.

The Khan-Tengri area is characterized by unstable weather, strong and prolonged snowfalls, severe frosts, and strong winds. The most stable weather is in late August — early September. However, by this time, it gets very cold, with temperatures reaching –25–30 °C, which, combined with strong winds, poses a significant obstacle for climbers. In July — August, the weather is usually quite changeable. In the second half of the day, clouds appear, and snowfall begins. Sometimes snowfalls continue for several days, with up to 1.0–1.5 m of snow falling.

Due to the high snowfall and the presence of winds, all ridge routes have huge snow drifts (cornices). Snow routes are objectively dangerous — avalanche risk! At altitudes of 6000 m and above, the snow remains loose and poorly connected to the ground. It is dangerous because the snow clings to almost vertical slopes.

The Central Tien Shan region is formed by schistose rocks that are quite heavily destroyed. The passage of individual sections of the ridge or slope is sometimes very difficult due to the lack of reliable insurance.

All the above-mentioned features of the area pose significant obstacles for climbers, and ascents made in the Central Tien Shan region are rightfully considered a measure of a group's courage and preparedness. The area remains little explored. Only the highest and most famous peaks have been conquered. Many peaks exceeding 6000–6500 m remain untouched, with no attempts even made to climb them.

Only one route has been laid to the summit of Khan-Tengri — along the western ridge. This is the easiest and safest path among the possible ascent routes.

But I won't be wrong if I say that perhaps the most beautiful and alluring route is the ascent to Khan-Tengri along the "marble edge".

This is a sharp, wind-sculpted white face that immediately catches the eye and remains in memory forever.

The features of the ascent along this route include the fact that:

- the "marble edge" starts at 6000 m;

- the approach to it is technically very complex and physically demanding;

- once on it, the only way to descend is through the summit — there are no easy descent paths.

Reconnaissance and Caching Trips. Training Climbs

The ascent along the "marble edge" to Khan-Tengri was preceded by:

- a series of reconnaissance trips;

- processing of the lower part of the wall;

- training ascents.

Initially, it was planned to storm the peak with a group of 8 people:

- Romanov B.T. — leader

- Bezlyudny V.I. — deputy

- Vorozhishchev V.V.

- Onishchenko V.P.

- Romanov V.I.

- Tkachenko A.N.

- Lavrinenko V.L.

- Smirnov A.Ya.

This composition conducted route reconnaissance, caching, and processing, as well as training climbs.

-

The first reconnaissance trip to examine the approach paths and choose the initial section of the route was conducted on July 11 by B. Romanov and V. Vorozhishchev.

-

II trip.

- On July 14, a group went to process the lower part of the wall and cache food, gasoline, and equipment:

- Bezlyudny P.I. — leader

- Onishchenko — doctor

- Romanov V.

- Tkachenko

Over the 4-day trip, the group observed the wall, laid a path through the icefall to the base of the wall, and processed sections R1–R3 (see diagram). During processing, 50 hooks were hammered in (32 regular rock hooks and 18 bolt hooks). 250 m of rope were hung on section R3. Ladder sections were hung: 2 pieces of 15 m and 5 pieces of 3-step ladders.

In total, 30 working hours were spent on processing and caching during this trip. At the top of the wall (section R3), a platform was laid, and a cache was left:

- gasoline — 8 l;

- food — calculated for 8 people × 500 g × 6 days;

- crampons — 1 pair;

- various rock hooks — 100 pieces;

- titanium ice hooks — 15 pieces;

- hammers — 3 pieces;

- various ladder sections — 10 pieces.

-

During the same period (July 14–18), a group of 10 people led by B. Romanov went to the saddle between Khan-Tengri and Peak Chapayeva (height approximately 6000 m). The tasks of this group included:

- organizing an intermediate camp for the group ascending Khan-Tengri via the western ridge ("usual" path) and for the group descending after climbing Khan-Tengri via the "marble edge". To this end, a cave for 15 people was dug on the saddle, and a cache was left: a) food — for 18 people for ½ day (500 g per person per day); b) gasoline — 8 l.

- Acclimatization of expedition participants. For this, a night was spent on the saddle (approximately 6000 m).

- Observing the "Marble edge" in profile and possible descent paths from the route.

- Observing the western ridge.

-

During the same period, Vorozhishchev, Lavrinenko, and Smirnov, as part of V. Yefimov's group, went to the upper reaches of the Inylchek glacier to scout and choose a path for ascending Peak 6725 m.

- On July 14, a group went to process the lower part of the wall and cache food, gasoline, and equipment:

On August 18, all groups gathered at the base camp and, after a 2-day rest, set out on July 20 for the third trip.

III trip: composition of the group and tasks of the third acclimatization and training trip:

-

Group

- Romanov B. — leader

- Bezlyudny

- Tkachenko

- Onishchenko

went to further process the lower part of the "marble edge" wall and examine the section of the wall leading under the "marble edge". This group processed sections R4–R7 (see diagram) over 3 days (July 20–23). At the top of section R7, at a height of 5150 m, a platform was laid, and a cache was left:

- gasoline — 9 l;

- food — calculated for 8 people × 500 g × 6 days.

During this trip, 22 hooks were hammered in (16 rock hooks, 5 ice hooks, and 1 bolt hook), 200 m of rope were hung, 5 five-meter and 4 three-step ladder sections were hung. 15 working hours were spent on processing.

-

Group

- Vorozhishchev V. — leader

- Romanov V.

- Smirnov A.

went to the area of the "Druzhba" glacier to the saddle between Peak Druzhba and Peak 6725 m (height 6000 m) to scout paths for ascending Peak 6725 m from the south.

IV Training and Acclimatization Trip

After conducting caching and reconnaissance-acclimatization trips, on July 24, the main group set out in full on a training ascent to Peak 6725 m from the "Druzhba" glacier. The group composition was:

- Romanov B. — leader

- Vorozhishchev

- Bezlyudny

- Onishchenko

- Smirnov

- Lavrinenko

- Tkachenko

- Romanov V.

From July 24 to 29, the group ascended Peak 6725 m from the south, spent a night at the summit, and safely descended to the base camp.

V. Organizational and Tactical Plan for the Assault

After completing the preparatory work and training-acclimatization trips, the final composition of the group was determined. Due to the technical difficulty of the route and the lack of suitable camping sites, it was decided that the group would consist of 6 people:

-

Romanov B. — leader of the assault group

-

Bezlyudny

-

Onishchenko

-

Romanov V.

-

Lavrinenko

-

Tkachenko

The group's departure was scheduled for August 4. With a 2-day gap, on August 6, a group of 14 people led by V. Vorozhishchev was to set out to assault Khan-Tengri peak via the western edge.

To monitor the main group during the passage of the lower part of the wall, an observation group was formed, consisting of:

- Smirnov

- Petiforov

- Kopalin

The observation group was to:

- monitor the main group's progress during the first 3–4 days of the assault until they reached under the "marble edge" (this part of the wall was not visible from the base camp);

- collect the extra ropes hung during route processing and boots.

Means of signaling with the group were agreed upon.

The tactical plan included:

- departing from the bivouac during the assault at 7:00–7:30 and moving for 10–12 hours a day.

- processing part of the route in the evening for 1–2 ropes.

- carrying three 45-meter ropes and a 60-meter auxiliary rope.

Non-standard equipment included:

- titanium hooks of various types and bolt hooks;

- duralumin wedges;

- 3-step, 5-meter, and 15-meter ladder sections;

- blocks.

When discussing the tactical plan, it was decided to proceed with 5 backpacks. The first climber went without a backpack, carrying a set of hooks, an auxiliary rope, and carabiners.

The rope teams were formed as follows:

- Romanov B. Romanov V. } 1st rope team

- Bezlyudny Onishchenko } 2nd rope team

- Tkachenko Lavrinenko } 3rd rope team

It is worth noting that the tactical plan was executed without changes. Hot meals were planned twice a day: in the morning and evening. In the middle of the day, dry rations and tea or coffee prepared the previous evening and carried in flasks were consumed.

Route Passage Order

Day 1. August 4, 1964. At 3:00, the main group, along with the observation group, left the base camp. The approach to the start of the route (base of the south wall) took 2.5 hours. Passing through the icefall under the wall took about an hour. We reached the route at 6:30. Five backpacks were carried. Since food, gasoline, and necessary equipment were cached along the route up to a height of 5150 m, the weight of the backpacks was approximately 8 kg (tent, bivouac gear, down suit, stove, and daily rations).

The observation group set up a bivouac on the glacier at the base of the wall (H = 4500 m).

After saying goodbye to our comrades, we began our ascent. The weather was good, the backpacks were light, the route was processed, and we had good training and acclimatization (we started the assault on the 26th day of our stay at the base camp after 4 training and acclimatization trips to a height of 6725 m), so our pace was high, and we were able to cover the entire processed section of the route in a day.

It took a total of 6 days (2 trips of 3–4 days each) and 45 working hours to process this section.

In total, we climbed 650 m (from 4500 m to 5150 m) according to the altimeter for the day.

The characteristics of the section covered are given in Table №1.

In addition to the table, it should be noted that this section of the route was one of the most technically challenging and labor-intensive. Section R3 (see diagram and Table №1) is passed without backpacks, with subsequent pulling of the same. The same had to be done when overcoming sections R5 and R7a. Movement along the ridge (sections R6 and R7) is complicated by the presence of:

- large cornices;

- icy, sharp ascents with deep, soggy snow that doesn't hold well on icy rocks.

Insurance on such sections is unreliable, so maximum attention and caution are required.

Day 2. August 5, 1964.

We left the bivouac at 7:30 and arrived at the next bivouac at 19:30, working for 12 hours. For the entire day, we climbed only 130 m (from 5150 m to 5280 m). The average steepness of the ridge is relatively small — about 25–30°. The work of this day was very physically and mentally demanding because there was virtually no movement along the ridge due to it being very sharp, crumbly, heavily snowed, and having large cornices on the left side. The ridge has a number of sharp, difficult-to-pass ascents ("feathers" or gendarmes). Therefore, most of the route for this day went along the steep right side of the ridge, across icy, crumbly rocks with unreliable insurance, and digging trenches in deep snow. We had to hammer in ice hooks or large wedges into the destroyed rock. To organize a night's stay, we had to cut down a huge snow cornice on the sharp ridge and lay out a platform in its place, which took about 1.5 hours.

Day 3. August 6, 1964.

We left the bivouac at 7:30. Right from the bivouac, a steep (50–55°) snow ascent began, leading to the next gendarme. It was impossible to bypass it; we had to dig a trench through the entire slope (260 m) because the steepness of the slope and the presence of deep (waist-deep) soggy snow made it impossible to move without a trench. Insurance in such snow would have been unreliable. V. Romanov spent 2 hours and 30 minutes hammering in rock hooks and wedges into the bottom of the trench to overcome these 260 m.

The further path along the ridge on this day was very similar to the route of the previous day. The same terrain character, the same complexities, and difficulties. Almost the entire day, the next climber ahead didn't part with a shovel, digging deep trenches in the right slope of the ridge (see photo R1).

Terrain features:

- The steepness of the snow ascents ("feathers") is close to vertical;

- Movement without a dug trench is impossible.

A day of упорной борьбы (persistent struggle).

We worked for 10 hours and 30 minutes, climbing only 170 m (from 5280 m to 5450 m). The entire day was spent working with great mental and physical tension. Insurance was unreliable; we had to move with backpacks since we were moving almost on a traverse. By 18:00, we approached a rock wall into which the ridge abutted. It was impossible to bypass it. Above this rock wall loomed a huge ice "cap" several tens of meters wide. This was the most invisible spot on the route that we couldn't examine. Until the last moment, it remained a mystery to us. We decided to stop for the night. Four of us began working: cutting down the corniced ridge and organizing a bivouac. The pair — Romanov B. and Onishchenko V. — started processing the wall. After processing the 40-meter wall and hanging a rope and ladders on it, the pair reached under the ice cap. It was impossible to bypass it. The ice thickness ended in both sides of the ridge with drops — it would have been fatal! The only path was upwards! After a closer look, the picture was discouraging. After a small snow ridge (10–15 m), there was an ice sheer drop, seemingly slightly overhanging; further on, there was a steep (45–50°) ice slope.

It took 2 hours to process and pass the ice sheer drop (using ice "screws" and ladders). We hung ropes and ladders and lowered them down. The comrades, having cut down a 2-meter ice ridge by this time, organized a bivouac. Below, under the ridge, we could see Vorozhishchev's group approaching. We gave a rocket signal — "all is well"!

Day 4. August 7, 1964.

Directly from the bivouac, the pairs ascended the 40-meter wall. We pulled up the backpacks. Having passed the processed part of the wall, we reached the ice. Onishchenko went first on crampons. 130 m of steep (45–50°) ice — 130 m of steps. We took turns leading. The weather was good. It took about 6 hours to climb these 130 m. Finally, we reached a wide snow plateau. Ahead lay a snow field at 20–25°. From here, the entire path was visible. The rest of the day was spent on calm, snowy work.

We stopped for the night at 19:00 on a wide snow ridge under a rock "finger".

Right in front of us was a sharp ridge of white marble. At the end of the edge stretched a wall of the pre-summit tower. A strong wind.

For the day, we worked for 11 hours and 30 minutes; we climbed 700 m (from 5450 m to 6150 m). 19 ice hooks were hammered in (part of the path was processed in the evening).

Day 5. August 8, 1964.

We departed at 7:30. It was cold, with a strong constant wind. Throughout the day, there was a monotonous roar, and we physically felt the pressure of the wind. The height (6150 m) and backpacks made themselves known. The "marble edge" turned out to be truly marble. It was composed of white metamorphosed limestone, smoothed by constant winds. The total length of the edge was about 900 m. The average steepness was about 40°, increasing to 50° in the upper part. This was a sharp, even ridge, divided into two unequal parts:

- the lower part — about 350 m;

- the upper part — 450–500 m.

Between them, there was a place to organize a bivouac. The steepness of the ridge was not great. The entire ridge was traversed with cross-harness hook insurance; there were no places to stop along the way, and there were holds for climbing. There were sections of highly smoothed slabs up to 12–17 m, where bolt hooks were hammered in, and ropes or ladders were hung. In general, movement along the "marble edge" turned out to be easier than we expected. There were no extreme climbing spots. Safe climbing was of medium difficulty, with sections of difficult climbing.

Around 13:00, the weather deteriorated — it started snowing, it got sharply colder, and visibility was limited to the length of a rope. But the path was examined, and there were no suitable stopping places, so we continued moving until late evening (until 20:30), still not finding a suitable platform.

We spent the night on the flattening upper part of the ridge. The bivouac was not very comfortable: we hammered in hooks, tied ourselves in, and climbed into a half-erected tent on a slope of about 20–25°. But there was no choice.

For the day, we worked for 13 hours. We climbed 550 m (from 6150 m to 6700 m).

Day 6. August 9, 1964. It was cold. Visibility was limited to 30–40 m. Snow. Somewhere above us was the wall of the pre-summit tower. But it was impossible to examine it and choose the easiest path. It was also difficult to assess its complexity. We decided to go straight up. The marble edge led directly to the pre-summit tower about 200 m high, the upper part of which gradually flattened out and led to the wide snow dome of the summit. The average steepness of the pre-summit tower was 70–75°, consisting of dark, crumbly, snow-covered, icy shale. Insurance was hook-based — we hammered in rock and ice hooks. The height made itself felt. Backpacks were pulled up on many sections. Very difficult climbing with the use of:

- ladders;

- grips.

It took almost 10 hours to overcome these 200 m. The entire day, snow was falling, and there was a strong wind. Goggles were constantly clogged with snow, but without them, the sun's glare hit the eyes hard. We climbed in masks with icicles hanging from them. At 16:00, we reached the summit. We set up a tent and went to sleep.

Day 7. August 10, 1964.

We departed at 7:00. In the morning, it began to clear up, the snowfall decreased, but visibility was still poor. We found a note from the Kazakhs dated 1962. We left our own note and began our descent. The descent path went along the western ridge:

- Initially along easy rocks;

- then along a steep snow ridge and rocks of medium difficulty to a platform at a height of 6800 m.

From the platform, we saw Vorozhishchev's group below, ascending towards us. The most difficult section of the descent was from the platform — about 120 m of steep, icy, heavily snowed rocks. Further down, along a wide couloir, we reached the ridge at a height of about 6600 m and then straight down along the ridge. Here we met Vorozhishchev's group. We chatted, wished them a safe journey, and continued our descent. At a height of 6400 m, we spent the night on a convenient platform. We walked for 10 hours and stopped at 17:00.

Day 8. August 11, 1964.

We departed at 7:30. We descended from the bivouac located at a height of 5400 m to the saddle between Peak Khan-Tengri and Peak Chapayeva. The descent from the ridge went along a steep, soggy snow slope. We decided not to take risks and stopped for the night in a cave (6000 m). We set up camp at 15:30. We walked for 3 hours.

Day 9. August 12, 1964.

We departed at 3:30. Avalanche-prone slopes were passed before sunrise. At 14:00, we returned to the base camp. During the ascent, V. Romanov kept a diary of the climb.

Actions of the observation group and communication organization. The observation group was necessary during the first 3 days of the assault, while passing through the lower part of the wall (up to section R16). The further path was clearly visible from the base camp. For this purpose, an observation group was formed, consisting of:

- Smirnov

- Petiforov

- Kopalin.

Having left together with the main group, they settled at the base of the wall on the glacier and monitored our movement. At the end of the first day, we dropped all the extra ropes and reepschnur hung on complex sections of the wall during processing, as well as boots. Further movement was in shekeltons with spikes.

Communication with the observation group and the base camp was planned via rockets. The observation group had a VHF radio station for communication with the base camp (about 1.5 hours away on foot). The groups were equipped with red and green rockets.

After reaching point R15, the main group was within sight of Vorozhishchev's group, which also had a VHF radio station and was within direct visibility from the base camp.

Additional Data

The team considers it necessary to additionally state the following: The route taken by the group is coherent, logical, and saturated with very complex technical sections, requiring participants to have excellent physical and technical preparation and moral resilience. Good acclimatization is required before tackling this route. The route, especially in the first part, is fraught with psychological moments because:

- the path for a long time goes along a sharp, destroyed, corniced ridge with steeply dropping walls;

- along which it is often necessary to bypass the ridge with not very reliable insurance;

- participants carry heavy backpacks.

It is difficult to deviate from the route. Therefore, in case of illness of one of the participants or prolonged bad weather, the group finds itself in a "trap" from which it is very difficult to escape. Therefore, when assembling a group, the most stringent requirements should be imposed on participants.

The total height difference of the route is 2500 m (from 4500 m to 6695 m).

The most complex sections of the path are:

- the lower part of the wall (from 4600 m to 5450 m);

- the exit to the ice "cap" (section R17);

- the pre-summit tower (section R25).

The team evaluates the route as category 6B.

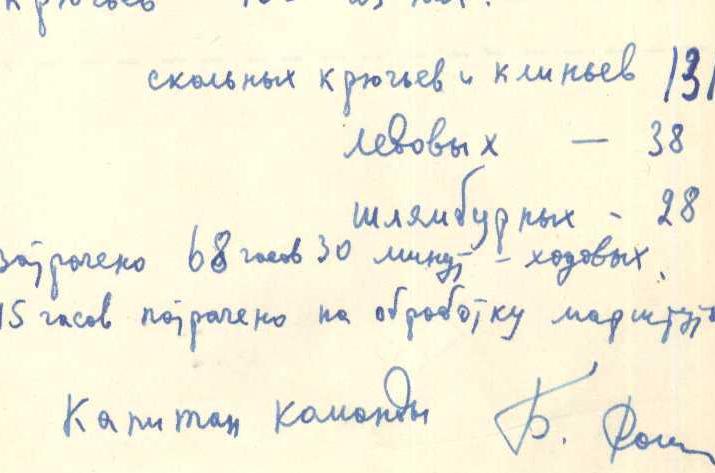

A total of 195 hooks were hammered in, including:

- rock hooks and wedges — 131;

- ice hooks — 38;

- bolt hooks — 28.

68 hours and 30 minutes of climbing time were spent on the ascent, and 45 hours were spent on processing the route.

Captain of the team B. Romanov.

List of Team Members

| Full Name | Year | Sports Rank | Position | Place of Work | Home Address |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Romanov Boris Timofeevich | 1926 | Master of Sports | Leader | Senior Researcher, Institute of Children's and Adolescents' Hygiene, USSR Academy of Medical Sciences | Moscow, Pushkinskaya St., 15/3, Apt. 11 |

| Bezlyudny Vladimir Ivanovich | 1932 | Master of Sports | Participant | Engineer, p/o 221/68 | Moscow, Varshavskoe Shosse, 186, Apt. 8 |

| Onishchenko Vyacheslav Petrovich | 1936 | Master of Sports | Participant | Doctor, Sports Dispensary №1 | Moscow, Staroye Shosse, 5/2, Apt. 4 |

| Romanov Vyacheslav Ivanovich | 1936 | Master of Sports | Participant | Senior Researcher, Institute of Experimental Biology, USSR Academy of Medical Sciences | Moscow, Bolshaya Peschanaya Sq., 1, Apt. 61 |

| Lavrinenko Vyacheslav Lazarevich | 1937 | Master of Sports | Participant | Senior Engineer, Gidrospetsproekt | Moscow, Komsomolsky Prospekt, 34, Apt. 52 |

| Tkachenko Alexander Nikolaevich | 1933 | 1st Sports Rank | Participant | Senior Engineer, MAI | Moscow, Leninsky Prospekt, 11, Apt. 131 |

Table of Main Route Characteristics by Sections

| № | Steepness, ° | Length, m | Terrain Characteristics | Climbing Difficulty | Insurance Features | Time, h:min | Hooks Hammered |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day 1. August 4, 1964 (4500 m — 5150 m) | |||||||

| R1 | 35 | 130 | Crumbly plate-like ridge | Easy rocks, partial insurance through ledges | Simultaneous movement | 0:30 | — |

| R2 | 40 | 120 |