Kazakhstan Republican Council of the Spartak Voluntary Sports Society

Report

on the ascent of Khan-Tengri Peak (6995 m) from the north by a team of climbers in August 1968 B. Studenin, 68

Almaty

1968

Introduction

A combined team of climbers from the Kazakhstan Republican Council of the Spartak Voluntary Sports Society consisting of:

- Studenin B.A. — Master of Sports, team leader

- Tokmakov V.S. — Master of Sports, deputy leader

- Afanasyev A.N. — Master of Sports, participant

- Zapeka V.N. — Master of Sports, —"—

- Ilyinsky E.T. — Candidate for Master of Sports, —"—

- Kambarov E.K. — Candidate for Master of Sports, —"—

- Popov V.M. — Master of Sports —"—

from July 29 to August 4, 1968, completed an ascent via a new route from the north to Khan-Tengri Peak.

The ascent was dedicated to the 50th anniversary of the Lenin Komsomol.

A Bit of History

Khan-Tengri Peak, unique in its strict and cold lines, has long attracted the attention of travelers, scientists, and climbers. As early as 1857, P.P. Semenov saw the Tengri-Tag ridge and the Khan-Tengri pyramid from the Kokjjar pass. In 1900, Italian climbers arrived to ascend Khan-Tengri Peak but were only able to determine from the Inylchek ridge that Khan-Tengri rises within the ridge dividing the Inylchek Glacier into two main branches.

In 1903, German geographer G. Mertsbakher reached the foot of Khan-Tengri Peak from the south.

For the first time, a group led by G.P. Sukhodolsky penetrated the northern slopes of Khan-Tengri in 1931. The climbers managed to:

- overcome the hazardous northern slope of the Tengri-Tag ridge;

- reach the eastern shoulder of Khan-Tengri (6200 m).

Unable to overcome the rocky wall of the northeastern ridge, they retreated. On the descent, the group narrowly escaped being caught in an avalanche.

The first ascent of Khan-Tengri Peak was made by a group from the Ukrainian expedition led by M.T. Pogrebetsky in 1931. The ascent was made from the south.

In 1932, a glaciological team led by A.A. Zhavoronkov (with guide V.F. Gusev) conducted research and mapped the Northern Inylchek Glacier. Gusev's group ascended to Peak Karlytau.

In 1936, two groups ascended Khan-Tengri Peak from the south:

- Kazakhstanis led by E.M. Kolokolnikov;

- a few days later — a sports group from the second All-Union Trade Union Central Council (VTsSPS) Alpine Games led by N.M. Abalakov.

In 1937, Alma-Ata climbers led by I.S. Tyutyunnikov ascended Peak Chapayeva (6371 m). The ascent to Peak Chapayeva was repeated in 1952 by army climbers led by V.K. Nozdrukhin.

In 1954 and 1962, Kazakhstanis (groups led by V.P. Shipilov and A.N. Maryashev) again ascended Khan-Tengri Peak from the south. Participants of the "Trud" expedition in 1962 ascended Peaks Chapayeva and M. Gorky (led by B.A. Gavrilov). In 1964, an expedition from "Trud" (led by B.T. Romanov) attempted Khan-Tengri from the south, while an expedition from the Soviet Academy of Sciences (S.K. AN SSSR) (led by E.I. Tamm) approached from the north.

The "Trud" expedition achieved:

- the first ascent of the Marble Ridge (group led by B. Romanov);

- an ascent via the standard route (group led by V. Vorojishev).

B. Yefimov's group made the first ascent from the south to Peak Shater (6700 m).

K.K. Kuzmin's group from the S.K. AN SSSR expedition pioneered a 6B category route from the north.

Mountain tourists have repeatedly penetrated the Northern Inylchek Glacier. For example, a group of Moscow tourists led by N. Volkov was the first to traverse the Karlytau Pass (between Peaks Karlytau and Kazakhstan in the Sarlydzhas ridge).

As evident from the history of exploring the Tengri-Tag ridge, the Northern Inylchek Glacier is less studied and explored than the Southern Inylchek Glacier, primarily due to its extreme inaccessibility.

The ascent to Khan-Tengri Peak from the north, via the Northern Inylchek Glacier, was planned by our team for 1967 but was postponed to 1968 due to circumstances beyond our control.

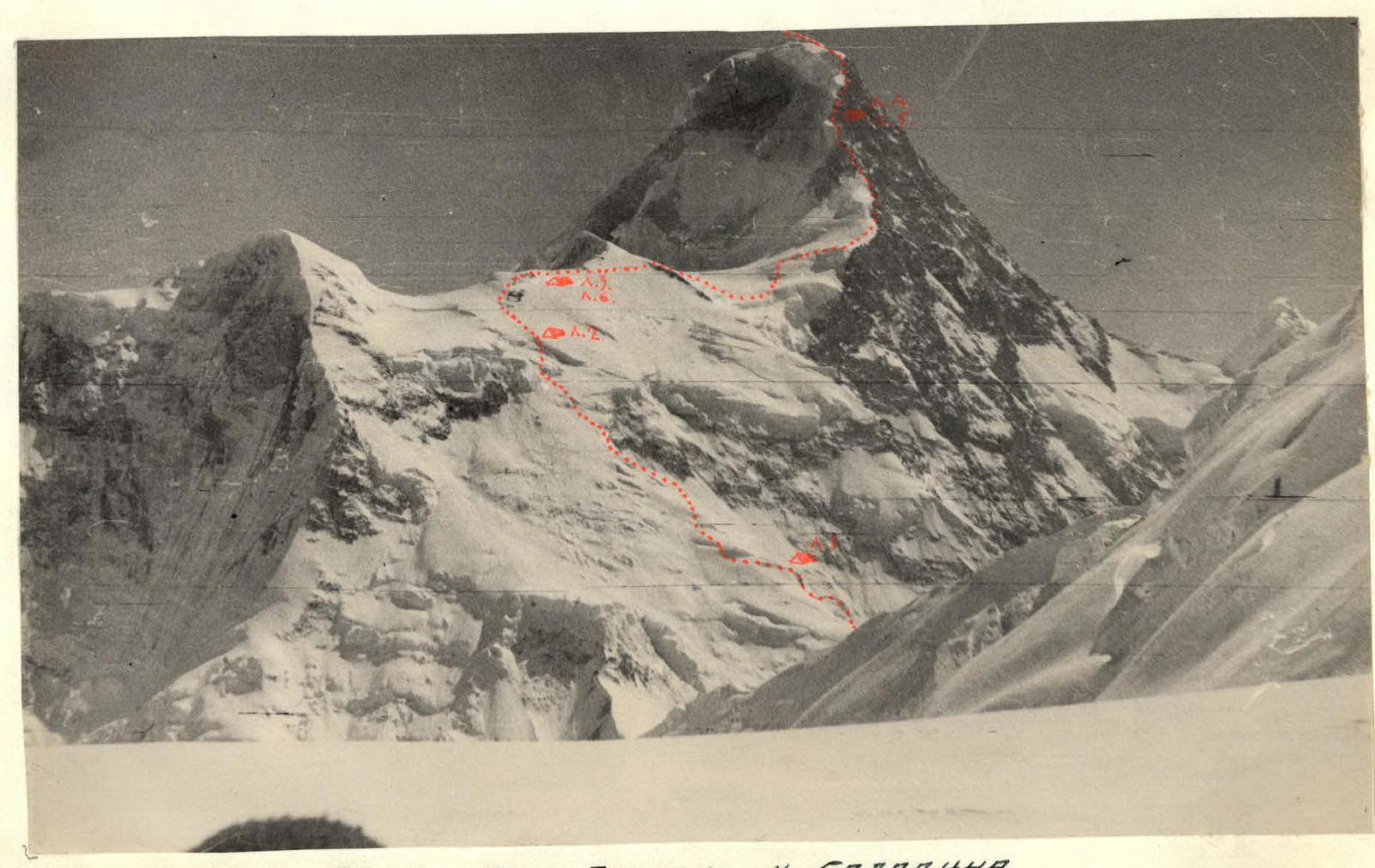

Only once before had an ascent to Khan-Tengri Peak from the north been made, by K.K. Kuzmin's group in 1964 (see photo).

ASCENDING KHAN-TENGRI AND SALADIN

even for well-prepared teams is a challenging task. The peak is high (6995 m) and technically difficult (finding a path to Khan-Tengri from the north below category 6 difficulty is hard). Moreover, the team must solve numerous tactical problems in rapidly changing conditions. (Weather and snow conditions in Central Tian Shan can change rapidly and drastically.) It is crucial to choose the safest routes, often requiring more complicated approaches.

The main hazards when ascending Khan-Tengri Peak from the north are:

- avalanches;

- ice falls;

- cornices;

- fragile, crumbling rocks;

- low temperatures;

- strong, gusty winds, especially above 6000 m.

Climbing Conditions

The Northern Inylchek Glacier area is the most inaccessible in Central Tian Shan. All expeditions and groups that have visited Northern Inylchek have approached from the west, from Lake Merzbacher. To reach the northern foot of Khan-Tengri Peak from Almaty, one had to:

- undertake a long (750 km, 3–4 days) car journey across several high mountain passes;

- cross the swift and turbulent Sarlydzhas River;

- transport goods by packhorses for several days to the Merzbacher meadow near the Southern Inylchek Glacier;

- navigate around Lake Merzbacher (a challenging task even for climbers);

- travel about 30 km with loads on their backs across the Northern Inylchek Glacier or establish a base camp far from the ascent objective.

After such an effort, not many had the strength and desire to conquer even such a coveted and now nearby Khan-Tengri.

After studying available materials on the area and conducting reconnaissance, we chose a fundamentally new, much shorter path via the Karlytau Pass in the Sarlydzhas ridge, with an elevation of 5100 m.

Our approach route to the base camp is as follows:

- 390 km of good and satisfactory roads from Almaty through Narynkol, Bayankol to Markulak in the Bayankol River valley;

- 8–10 km of packhorse trails along the Bayankol River valley to the tongue of the Marble Wall Glacier (the glacier has no terminal moraine, usually a significant obstacle);

- 8–10 hours of walking across the short Marble Wall Glacier and ascending to the Karlytau Pass.

The descent from the Karlytau Pass to the base camp site on the right lateral moraine of the Northern Inylchek Glacier near the Karlytau Glacier takes 1–2 hours with a load.

However, this path is not as straightforward as it may seem. We "rate" the route to Peak Karlytau from the Marble Wall Glacier as category 4 difficulty. And ascending Peak Karlytau from the pass takes no more than 2–3 hours of intense, challenging work.

The nearest settlement — the outpost and geologists' village Bayankol — is approximately 45 km from the base camp. In case of necessity, this distance from the base camp can be covered on foot in one full day. Cars occasionally visit Zharkulak (formerly a prospectors' settlement) 18 km from the base camp.

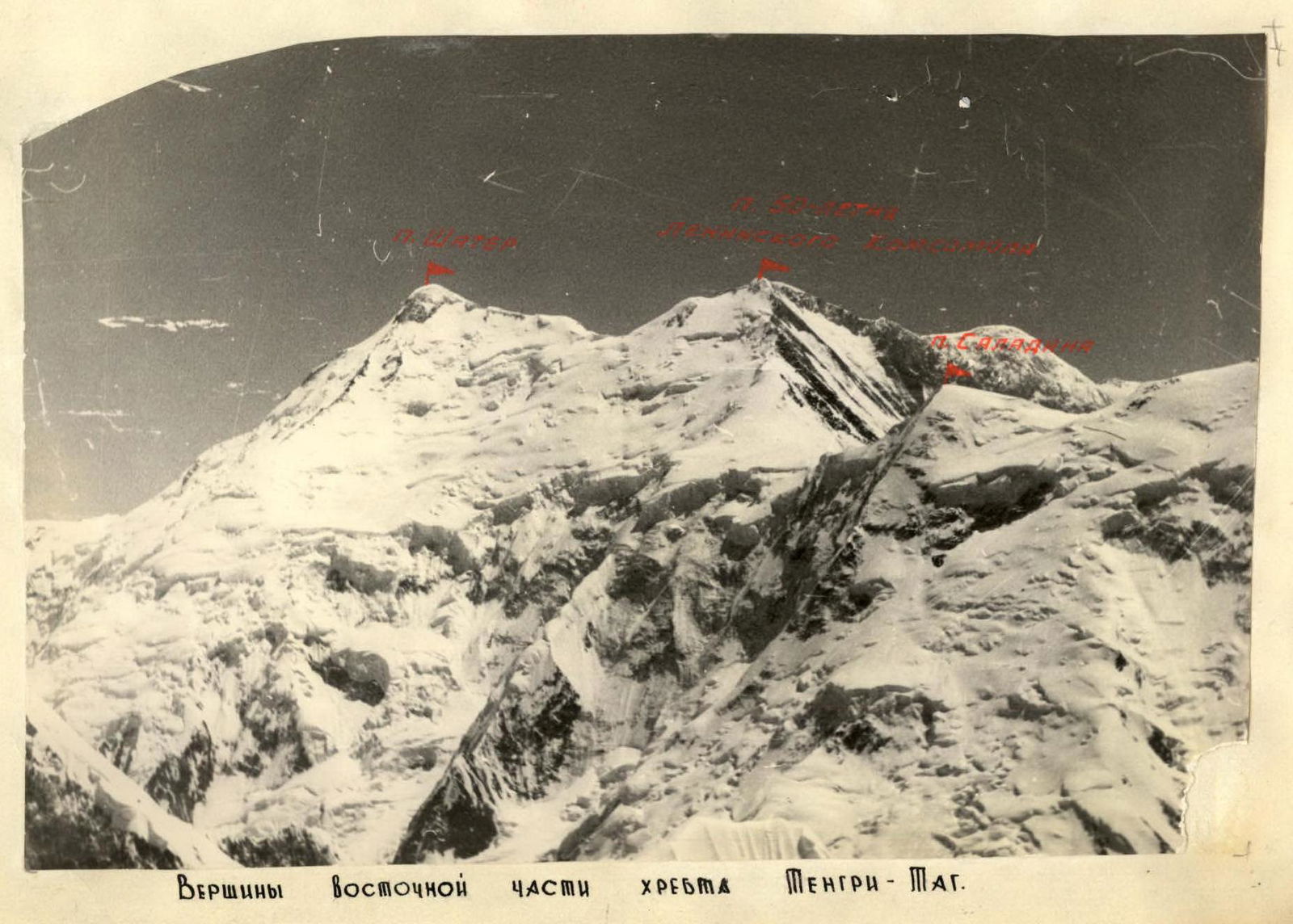

The relief of the northern slopes of the eastern part of the Tengri-Tag ridge, the second-highest ridge in Tian Shan.

The Tengri-Tag ridge branches off from the Meridional ridge near Peak Shater, about 6700 m high. The crest is narrow, snow-rocky, with numerous cornices, steeply dropping to both the south and north, and nowhere on the Shater–Khan-Tengri section does it drop below 5800 m. The rocky outcrops are composed only of sedimentary rocks from two suites.

- The lower suite consists of carbonaceous-clay, clay, calcareous-clay, and other shales. Organic remains found in them indicate that where the nearly seven-thousander now stands, there was once organic life several hundred million years ago.

- The upper suite is composed of marbleized limestones and marbles. The sediments apparently underwent contact metamorphism (there are many young intrusive bodies of acidic composition further north).

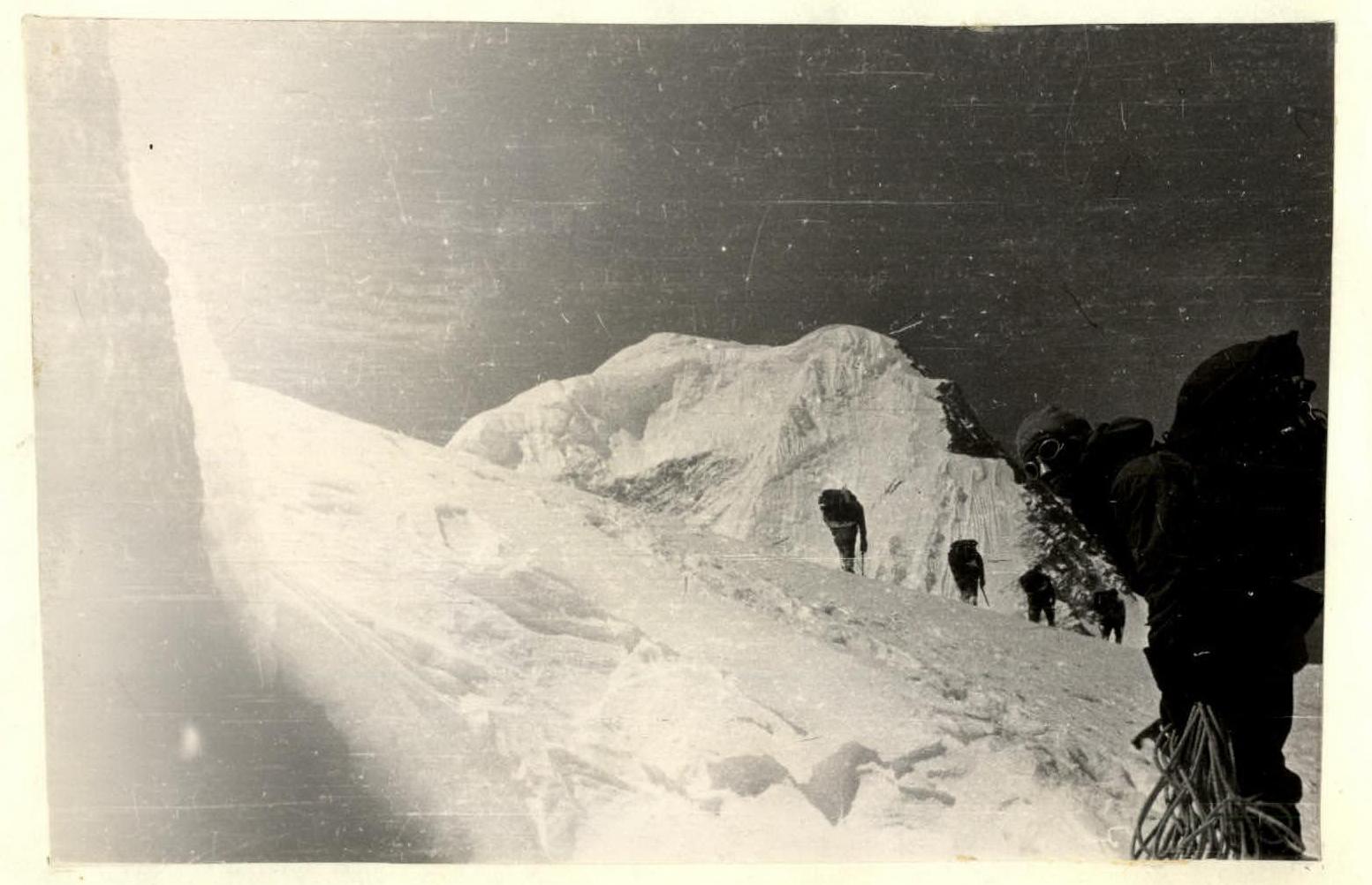

The boundary between the two suites is particularly visible in the area of Peak 50 Years of the Lenin Komsomol and the northern wall of Khan-Tengri Peak. The rocks are fragile and unreliable. The northern slopes of this part of the ridge are less accessible to climbers than the southern slopes. The ice-snow slopes are very steep (average steepness over 50°) with numerous steep, sometimes sheer, ice "foreheads" and active icefalls. Periodically, multi-ton blocks of ice break off from the main mass and crash down with great speed and a roar. The echo of the icefall still resonates, and snow dust settles on the glacier, surrounding rocks, and tents...

Only the nearly three-kilometer northern wall of Khan-Tengri Peak and sections of the northern counterforts of Peaks Shater and Saladin, along with a few nunataks, are completely free of ice.

The weather in Central Tian Shan is extremely unstable, with abundant precipitation and strong, gusty westerly winds. Bad weather can persist for several days or weeks with short breaks. Sometimes, more than a meter of snow falls in a single cycle, creating additional difficulties during ascents.

The weather conditions in the summer of 1968 can be considered good. The wind was sometimes very strong, and the air temperature occasionally dropped below -20°C, but there were no significant snowfalls. Sunny weather with wind prevailed for more than half of our stay on the Northern Inylchek, creating favorable snow conditions in the area. In a snowier summer, many of our ascents would have been impossible or too hazardous to attempt. In this regard, the route of the S.K. AN SSSR expedition is somewhat better, although it is apparently not...

Description of the Ascent to Khan-Tengri Peak from the North

On July 29, the team departed from the base camp early at 4:00 AM. Rucksacks were heavy, despite some supplies and fuel already being at the cave higher up. The glacier was well-known to us, and with minimal snow cover, crevasses were visible and safe. We immediately set out onto the ice from the moraine, moved quickly down the glacier, and, crossing it, approached the northern slopes of Khan-Tengri. This 1.5 km section took 40 minutes. It was cold, and the frozen snow provided good footing. We approached the snowy slopes and linked up.

Section 2. A gentle snow-firn slope, 200 m, proceeded simultaneously.

Section 3. The snow slope turned into a firn slope, with steepness gradually increasing to 35°.

Section 4. Steepness increased to 45°. We ascended with variable insurance through an ice axe. The cold but calm night gave way to an excellent morning. Not a cloud in the sky, and the climbers' mood was equally cloudless!

Section 5. We traversed a firn gully and passed an ice wall ending in a horizontal snow shelf.

Actions performed:

- Cut steps;

- Hammered in ice screws;

- Hung ropes.

It was not easy to move along them as the direction was to the left of vertical, and the rucksack pulled sideways.

Section 6. The horizontal snow shelf led us left, bypassing a steep ice rise. There was ice there too, but not as steep.

Section 7. An ice wall with a steepness exceeding 60°. 30 meters were traversed with step-cutting, 2 ice screws were hammered in, and ropes were hung.

Section 8. An almost horizontal snow shelf bypassed a wide crevasse. We moved simultaneously.

Section 9. A steep (about 70°) ice wall. Its height was about half a rope length, but passage was complicated.

Sections R10–R11. We traversed a firn slope of moderate steepness to the left and upwards.

Section 12. We overcame an ice wall with step-cutting and ice screw insurance. Steepness was 50°.

Section 13. We advanced simultaneously along a snowy slope towards an ice wall.

Section 14. No safe bypass for the ice wall was found. Studenin put on crampons. The silence of the mountains was broken by the ringing blows of an ice axe and the continuous striking of a hammer. The others, having removed their rucksacks, enjoyed the respite. Once the ropes were hung, passing with rucksacks required maximum effort.

Sections R15–R16. While the others ascended via the ropes, Ilyinsky, having moved along a snowy shelf to the left and upwards, hung new ropes.

Section 17. A prolonged snowy slope with a steepness of about 45°. Deep snow held steps well. Popov and Zapeka worked ahead, taking turns with insurance through an ice axe. The others waited for their turn under the ice wall on a ledge, careful not to overload the slope.

Section 18. Another steep rise with a thin layer of snow. Kambarov, who went ahead, hammered in an ice screw.

Sections R19–R20. We attempted to bypass an ice fall by traversing left but had to ascend along the left boundary of the fall. To the left were steep, avalanche-prone snowy fields.

Sections R21–R23. We ascended along a vaguely defined snowy ridge with occasional steep ice sections. The snow condition instilled confidence in the safety of our progress. We reached a gentle section of the ridge, a safe place for a bivouac. The most likely avalanche paths lay to the left and right of this gentle section. We set up for the night. Deep, dense snow allowed us to protect our tents from the wind with walls made of snow bricks. We used:

- saws;

- shovels.

Sections R25–R30. We departed at dawn. Quickly gained altitude. The snowy slope became very steep in places. Several steep ice outcrops required step-cutting and hook-hammering.

Sections R31–R39. We reached a snowy ridge again. 40 m of a steep ice rise. Steepness was 50°. We moved left and upwards towards an ice fall. A convenient ledge before the fall. The fall was protected from avalanches and wind by an ice overhang. We assessed the ledge's advantages and disadvantages regarding avalanche danger and set up tents.

The snow condition on the second day of the ascent gradually worsened with altitude, becoming drier and more powdery. The top layer was softened by the bright sun, but beneath it lay dry, powdery snow where a footstep could hardly find support, sliding on the icy base. Thus, ascending steep snowy rises required careful step-tamping and caution when following.

Section 40. Considering the worsening snow conditions, we departed early in the morning. An ice wall with step-cutting and hook insurance.

Section 41. A steep snowy slope, two rope lengths long.

Section 42. An ice wall with 70° steepness. Two rope lengths with step-cutting. 4 hooks were hammered in.

Section 43. A snowy ledge led to an ice rise.

Section 44. Two hooks were hammered in for insurance when passing the rise.

Sections R45–R49. The ascent path lay towards a large ice fall.

Section 50. We bypassed the fall to the right. A steep ice section.

Section 51. A steep snowy slope, 70 m long, finally led to the eagerly awaited ridge.

Section 52. We moved along a gentle snowy ridge, reaching the cave.

The third day of the ascent demanded maximum effort and caution from the participants in choosing the route and navigating steep snowy and icy rises.

Favorable weather conditions, acclimatization, and the participants' training contributed to a successful ascent to the Khan-Tengri plateau.

Section 53. A gentle snowy ridge with minor steep rises. Progress was easy; dense snow held body weight well. The weather was good, but a sharp wind made us huddle and zip up our down jackets. We approached the depression.

Section 54. We descended into the depression. Snow was loose, requiring considerable effort to clear a path. Attempting to "ease" the journey by following snowy ridges (drifts) was unsuccessful.

Sections R55–R58. The initial ascent from the depression involved a steep snowy slope with deep snow. The leader, breaking trail, sank deeply. We had to dig a trench, using knees as a battering force.

After this section, we entered:

- a relatively easy section in a small icefall.

Then:

- we turned right;

- passed between two ice walls;

- performed more "knee work".

The exit to the ridge was simpler. On the ridge, we encountered a sharp westerly wind, which remained with us throughout our ascent to the summit and descent.

Section 59. We moved along the ridge on a steep firn slope (45°). Steps were cut with difficulty; insurance was through an ice axe. We found traces of the "Burevestnik" group's presence: 3 pairs of crampons frozen in place and a blue canister (though punctured). We considered this a "welcome to subsequent climbers" and continued towards the beginning of the rocky ascent route to Khan-Tengri.

Section 60. Easy, crumbling rocks; movement was simultaneous. We approached the rocky wall.

Section 61. The rocky wall was climbed directly towards a standalone block. Climbing was challenging. The wind hindered progress, blowing snowflakes from the slope and hurling them forcefully into our faces. Protection from this "bombardment" was impossible.

Section 62. Three нависающих скальных участка по 1,5–2 м, followed by a flattening of the wall, and further, traversing left and upwards, it led to a snowy ridge. Climbing was challenging, requiring great attention to avoid dislodging loose rocks from the fragile wall.

Sections R63–R65. From the ridge, we moved right and upwards along rocky ledges to a rocky wall (1.5 rope lengths). The rocks were difficult, with a final exit from the upper to a gully, which then became snowy and icy. Insurance was via hooks and ledges. All, except the leader, used ropes.

There was a convenient spot on the snowy ridge for 2–3 tents. We leveled the area with a saw, built a windproof wall almost as tall as a person. Now, we were not afraid of the strong, gusty wind, especially fierce on the ridge and ready to sweep us away.

The altitude was approximately 6700 m. While five of us were engaged in construction, two went to process a complex, heavily snowy rocky section.

Section 66. Early on August 2, despite strong winds and morning cold, we set out lightly on the route. We took a small supply of food, a tent, and a "Febus" heater as a precaution. Everyone felt well. The path from the bivouac to the rocks followed a snowy ridge of moderate steepness.

Section 67. Snowy rocks with ice became increasingly steep. Three rope lengths of complex rocks. The pre-hung ropes proved very useful, becoming thick and prickly but ensuring the safety of the passage. Wind, cold, and occasional poor visibility.

Section 68. We emerged onto a snowy ridge. Snow was dense; steps were cut well. We moved simultaneously.

Section 69. The steepness of the snowy slope increased. We proceeded alternately with insurance through an ice axe. Snow was reliably bonded to ice. Still, we looked back, wary of any mishap. Leading teams took turns, as the high altitude was felt. Strength was quickly restored when following in the tracks. We didn't need to stop for rest.

Section 70. A gentle section of the snowy ridge led to a rocky "tooth".

Section 71. We bypassed the "tooth" along a steep snowy slope. Many convenient and fairly reliable rocky outcrops were used for insurance.

Section 72. Maneuvering through a system of ledges, we bypassed a section of complex, crumbling rocks.

Section 73. A rocky wall of crumbling limestone shale. A hammer struck. Occasionally, small stones flew by, not gaining much speed and posing no danger. Further down, they crashed with a loud noise.

Section 74. Finally, we reached a gentle snowy ridge. Immediately, we felt the full force of the gusty westerly wind, the master here. It didn't want to let us reach the summit, blowing against us, throwing handfuls of snowy grit into our faces (painful!), obscuring goggles, and making breathing even more difficult. The proximity of the summit gave us strength. Bent over, shielding our faces from the wind, we moved upwards.

Section 75. The weather was clear. Frost. We ascended to the summit via snowy rises and crumbling rocks. From the summit plateau, a vast panorama of mountains unfolded.

We immediately found a cairn with two large stones:

- A note from V.P. Shipilov's group dated 1954.

After examining nearby rock outcrops, we discovered another cairn:

- A note from K.K. Kuzmin's group dated 1964.

We spent about two hours on the summit, left our notes in both cairns, and began our descent along the ascent route.

The route was completed in 7 days of intense work.

Conclusion

The expedition by climbers from the Kazakhstan Republican Council of the Spartak Voluntary Sports Society to the Northern Inylchek Glacier lasted one month.

During this time, the main group completed two challenging routes of the highest category, first ascended two six-thousanders (Peaks Saladin and 50 Years of the Lenin Komsomol), and for the first time, seven people twice ascended Khan-Tengri Peak.

Members of the auxiliary groups first ascended Peak Odinnadtsat (5437 m; climbers in 1957 reached only the lower, eastern summit), and traversed 6 new routes.

A new approach route to the Northern Inylchek via the easily accessible Bayankol River valley was discovered and tested. The route is challenging but saves much time and effort.

All these achievements are the result of years of searching and work by our team.

The event was conducted in full compliance with the rules for alpine events in the USSR, without injuries or failures.

In the base camp, there was a case of flu-like illness in young participant N. Khrebtov, who received necessary assistance and quickly recovered.

Comparing the route taken with others completed in recent years by our and other teams, we believe its difficulty can be rated as the highest 6B category.

The event was dedicated to the 50th anniversary of the Lenin Komsomol.

On behalf of the team, trainer and captain, Master of Sports: B. Studenin

Table of Main Characteristics of the Ascent from the North to Khan-Tengri Peak

The route's height difference is 2500 m, including the most challenging sections:

| Dates | Section # | Average Steepness | Section Length | Characteristics by Relief | Characteristics by Technical Difficulty | Characteristics by Passage Method and Insurance | Characteristics by Weather | Departure Time | Bivouac Time | Working Hours | Rock Hooks | Ice Hooks | Shoulder Hooks | Camping Conditions | Daily Ration Weight |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 |

| 29.07 | R1 | Approaches via a calm glacier to the foot of Khan-Tengri's northern wall | 1000 | ||||||||||||

| 1500 m | Calm glacier | Easy | Simultaneous movement | Good | 4:00 | 13:30 | 9:30 | ||||||||

| R2 | 200 m | Snow-firn slope | Easy | Good | |||||||||||

| R3 | 35° | 120 m | Firn slope | Easy | |||||||||||

| R4 | 45° | 60 m | Medium | Alternate movement, insurance via ice axe | |||||||||||

| R5 | 50–55° | 40 m | Ascent from a gully to an ice wall | Challenging | Ascent via ropes, step-cutting, 2 hooks | 2 | |||||||||

| R6 | 10–15° | 30 m | Snowy ledge | Easy | Simultaneous movement | ||||||||||

| R7 | 60–65° | 30 m | Ice wall | Challenging | Step-cutting, movement via ropes with hook insurance | 2 | |||||||||

| R8 | 15° | 50 m | Bypass along a snowy ledge of a crevasse | Easy | Simultaneous movement | ||||||||||

| R9 | 70° | 25 m | Ice wall | Challenging | Step-cutting, hook insurance | 2 | |||||||||

| R10 | 45° | 50 m | Firn slope | Medium | Alternate movement, insurance via ice axe | ||||||||||

| R11 | 35° | 25 m | Firn slope, traverse left-upwards | Easy | Simultaneous movement | ||||||||||

| R12 | 50° | 20 m | Ice wall | Challenging | Step-cutting, ropes, hooks | 2 | |||||||||

| R13 | 35° | 120 m | Snowy slope | Easy | Simultaneous movement | ||||||||||

| R14 | 60° | 40 m | Ice wall | Challenging | Step-cutting, ascent via ropes, hook insurance | 4 | |||||||||

| R15 | 20° | 10 m | Snowy ledge | Easy | Simultaneous movement | Good | |||||||||

| R16 | 65° | 15 m | Ice wall | Challenging | Step-cutting, hook insurance | 1 | |||||||||

| R17 | 45° | 100 m | Snowy slope | Medium | Alternate movement, insurance via ice axe | ||||||||||

| R18 | 60° | 30 m | Ice wall | Challenging | Step-cutting, hook and ice axe insurance | 3 | |||||||||

| 30.07 | R19 | 25–30° | 20 m | Snowy ledge | Easy | Simultaneous | |||||||||

| R20 | 60–65° | 50 m | Ice wall | Challenging | Step-cutting, hook insurance, movement via ropes | 5 | |||||||||

| R21 | 45° | 90 m | Snowy-firn slope | Medium | Alternate movement, insurance via ice axe | ||||||||||

| R22 | 55° | 35 m | Ice wall | Challenging | Step-cutting, hook insurance | 3 | |||||||||

| R23 | 45° | 85 m | Snowy slope | Medium | Alternate movement, insurance via ice axe | ||||||||||

| R24 | 70° | 25 m | Ice wall | Challenging | Step-cutting, hook insurance | 2 | Good, alt. 5300 | ||||||||

| R25 | 40° | 100 m | Snowy slope | Easy | Simultaneous | 6:00 | 14:30 | 8:30 | 800 gr. | ||||||

| R26 | 45–50° | 38 m | Ice wall | Medium, challenging | Step-cutting, hook insurance | 2 | |||||||||

| R27 | 40° | 40 m | Snowy slope | Easy | Simultaneous | ||||||||||

| R28 | 55° | 25 m | Ice wall | Challenging | Step-cutting, hook insurance | 2 | |||||||||

| R29 | 25–30° | 120 m | Snowy slope | Easy | Simultaneous | ||||||||||

| R30 | 45° | 30 m | Ice wall | Medium, challenging | Step-cutting, hook insurance | ||||||||||

| R31 | 35° | 120 m | Exit to a snowy ridge along a slope | Easy | Simultaneous | ||||||||||

| R32 | 50° | 40 m | Ice wall | Challenging | Step-cutting, hook insurance | 4 | |||||||||

| R33 | 45° | 50 m | Snowy slope | Medium | Alternate movement, insurance via ice axe | ||||||||||

| R34 | 60–65° | 20 m | Ice wall | Challenging | Step-cutting, picket insurance | Good | 2 | ||||||||

| R35 | 45° | 30 m | Snowy slope | Medium | Alternate movement, insurance via ice axe | ||||||||||

| R36 | 60° | 20 m | Ice wall | Challenging | Step-cutting, picket insurance | 2 | |||||||||

| R37 | 45° | 50 m | Snowy slope | Medium | Alternate insurance via ice axe | ||||||||||

| R38 | 70° | 35 m | Ice wall | Challenging | Step-cutting, picket insurance | 3 | |||||||||

| R39 | 35° | 20 m | Snowy ledge | Easy | Simultaneous | Camp (5800 m) | |||||||||

| 31.07 | R40 | 65–70° | 10 m | Ice wall | Medium | Step-cutting, hook insurance and via ice axe | 6:30 | 14:30 | 8:00 | 800 gr. | |||||

| R41 | 45–50° | 65 m | Snowy slope | Challenging | Step-tamping in powdery snow | ||||||||||

| R42 | 70° | 55 m | Ice wall | Challenging | Step-cutting, hook insurance | 6 | |||||||||

| R43 | 35° | 20 m | Snowy ledge | Easy | Simultaneous | ||||||||||

| R44 | 60° | 30 m | Ice wall | Challenging | Step-cutting, hook insurance | 2 | |||||||||