Report

On the Ascent of Peak Pobeda (7439.3 m) by the Joint Expedition of the Spartak Society and the Kazakh Alpine Club in July-August 1956

1. Description of the Area, Brief Description of Previous Ascent Attempts, and Expedition Objectives

Peak Pobeda (7439.3 m) is located in the eastern Tian Shan, in the East Kok-Shaal-Tau range, along the state border between the Soviet Union and the Chinese People's Republic. The section of the range where Peak Pobeda is situated stretches latitudinally and represents a vast glaciated massif - a wall about 15 kilometers long, sharply rising above the surrounding mountains. Even the lowest parts of the wall exceed 6.5 km in height.

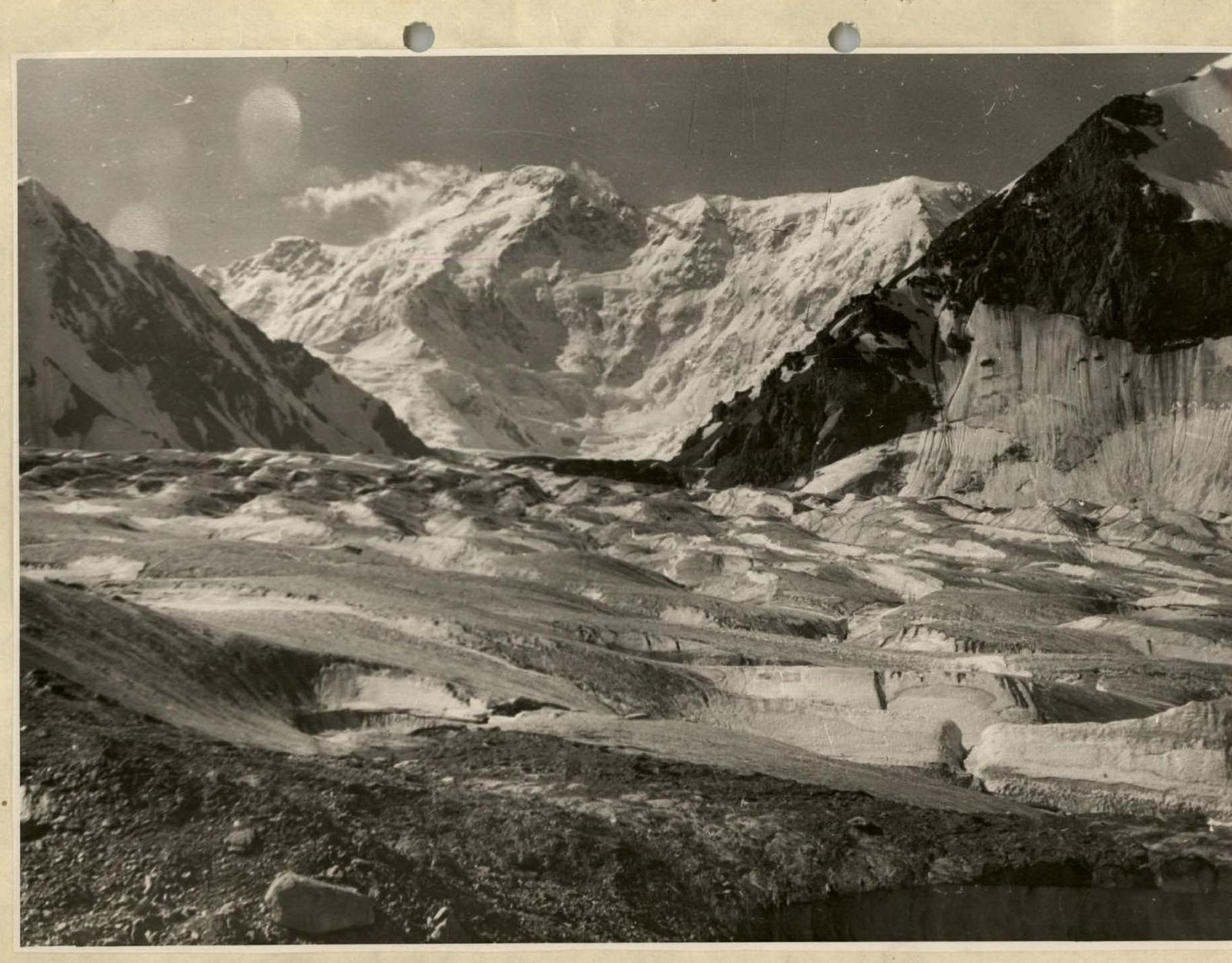

At the foot of the northern slopes of the wall lies the Zvezdochka Glacier, a major tributary of the Inylchek Glacier. The wall rises above the Zvezdochka Glacier throughout its length by 2.5-3 km.

The highest point of the massif, Peak Pobeda (7439.3 m), is located in the middle part of the massif. Here, the ridge is elevated 600-700 m above the rest of the range for about 500-600 m, with no significant changes in height along this section. On the northern slope of the wall, a prominent counterfort extends towards the Zvezdochka Glacier.

To the east, the massif is bounded by the sharp and deep Chon-Tareng pass. The pass saddle is limited on the side of Peak Pobeda by a local rise in the ridge (about 6900 m), which we will conditionally refer to as the Eastern Peak of Pobeda. To the northeast of the pass lies Peak Voennykh Topografov (6873 m), from which a heavily dissected ridge, Ak-Tau, extends westward.

In the Ak-Tau ridge, there are five small glaciers, parallel to each other, which are northern tributaries of the Zvezdochka Glacier. To the southeast of the Eastern Peak of Pobeda, on Chinese territory, a weakly dissected ridge extends for 10-15 km, with heights exceeding 6500 m throughout.

South of Peak Pobeda, on Chinese territory, lies a complex mountain node with numerous peaks. None of these peaks, as observed visually, reach the height of Peak Pobeda.

To the west of the highest point, the massif of Peak Pobeda is adjacent to a relatively low ridge, known as the Diky ridge, on the northern side. The wall of Peak Pobeda continues westward, beyond the Diky ridge and the Diky Glacier, ending at a peak (6537 m) located in the upper reaches of the Proletarsky Tourist Glacier.

The usual approach routes to Peak Pobeda start from the town of Przhevalsk. From Przhevalsk to the village of Ottuk, there is a motorable road, which is well-maintained. From Ottuk, a vehicle can travel another 19 km, initially along the river Ottuk, and then along the right (orographically) bank of the river Sary-Dzhas. In the upper part of the journey, there is no road, and the vehicle travels along the relatively flat grassy bank of the river. The vehicle-accessible path ends at the Ken-Su stream, a right tributary of the Sary-Dzhas River, which joins it about 10 km below the mouth of the T yuz River.

The expedition's cargo was transported to this point from Przhevalsk using seven three-ton trucks. Here, a transshipment base was established, where a radio operator and a logistics officer were stationed. Beyond this point, there is only a pack trail.

The trail initially follows the right bank of the Sary-Dzhas River. Crossing the Sary-Dzhas River can be done by fording on horseback near the mouth of the T yuz River. We crossed above this point, on the backwaters located four kilometers upstream from the T yuz River mouth.

The trail then proceeds upstream along the right bank of the T yuz River, up to the T yuz pass. The trail is well-maintained as it is used for driving livestock to winter pastures.

We used the Achi-Tash pass (4100 m) to cross the Sary-Dzhas ridge, as the ascent to it is somewhat simpler than to the T yuz pass, which is directly adjacent to it on the left. After traversing the glacier at the upper part of the ascent to Achi-Tash and reaching the pass point, the caravan followed a broad, gravel-covered ridge to the T yuz pass, from where it descended into the Inylchek valley, saving 15 km of travel along the valley.

The descent from the Achi-Tash pass into the Inylchek River valley initially follows small scree slopes, and then the trail emerges onto grassy slopes.

On the right bank of the Inylchek River, near a large stone, 1.5 km below the tongue of the Inylchek Glacier ("Chon-Tash"), an intermediate transshipment base was established, where a radio operator was stationed. Here, there are excellent pastures for horses and clean drinking water.

From Chon-Tash, the trail, crossing minor tributaries of the Inylchek River that are filled with water only when the Merzbacher Lake bursts, leads to the left side of the Inylchek Glacier tongue, from where the main flow of the Inylchek River originates. Without crossing it, the trail transitions onto the terminal moraine of the glacier and follows it for about 5 km. On this section, we had to re-lay the trail for horses, clearing large stones and filling numerous pits and crevices. Then, the path transitions from the ice to the left lateral moraine, where the trail is well-preserved over the years, except for one or two sections of scree and cliffs, which require returning to the glacier to bypass.

19 km above the glacier tongue, on the left bank, there is a slightly sloping and somewhat marshy grassy area - the so-called Merzbacher meadow, approximately 1/8 sq. km in size. The grass reserve here was sufficient for our caravan of sixty horses for the entire duration of the expedition.

On the meadow, there is a stream with good drinking water, located on the eastern edge of the area.

About 1.5 km upstream (at the mouth of the Shokal'sky Glacier), there is another meadow that can serve as a pasture.

Above the Merzbacher meadow, the trail again transitions onto the Inylchek Glacier and continues along it. For the first three kilometers, we had to almost completely re-lay the trail for horses.

Further on, the path emerges onto a relatively flat median moraine of dark color, composed of small stones, and the road somewhat improves.

We managed to lead the horses to the confluence of the Zvezdochka Glacier, where, at an altitude of about 4100 m, on a small gravel moraine near the slopes of the Diky ridge, the expedition's base camp was established.

There is no fodder for horses in the vicinity, which necessitates delivering oats to them for the entire duration of their stay in the camp.

This location is 5-6 km downstream from where previous expeditions had set up their base. However, over the past year, the glacier at the confluence of the Zvezdochka and Inylchek glaciers had deformed significantly, with many open crevices forming, rendering the previous trail almost completely destroyed. Restoring the trail would have required a significant waste of time.

The most challenging section of the caravan route is the 40-kilometer stretch from the end of the glacier tongue to the base camp. Here, great attention is required when choosing the path, and constructing a trail on several sections.

The journey from the end of the motorable road to the base camp near the Zvezdochka Glacier took us 7.5 days when traveling upstream, including two rest days - at Chon-Tash and on the Merzbacher meadow - for trail construction. The prolonged duration of the first trip to the base camp was also due to the horses being unbroken and the inexperience of the caravan handlers. Subsequently, this path was traversed by the caravan in 4 days. On the descent, with a large and heavily laden caravan, one of the expedition's groups completed the entire path in the reverse direction in three days, with people riding horseback and the caravan moving for 10-12 hours a day.

From the base camp, there are several variants of approaches to the foot of Peak Pobeda.

The most direct variant, which we used subsequently, proceeds for about 1-1.5 km along a gully between the glacier and the slopes of the Diky ridge, to a glacier fall at the confluence of the Zvezdochka Glacier into the Inylchek Glacier. From here, one needs to turn sharply south, bypassing a rocky outcrop of the Diky ridge spur, and emerge onto a flat, gentle left lateral moraine of the Zvezdochka Glacier.

The Zvezdochka Glacier is then crossed in the direction of the northwest edge of the Ak-Tau spur, where the glacier makes a turn from a meridional to a latitudinal strike. Movement in this section is done by avoiding numerous crevices; the middle part of the glacier is the simplest and is usually used for ascent.

Near the turn of the glacier, at the Ak-Tau spur, there is a glacier fall, which is most conveniently bypassed by exiting onto the rocky slope of Ak-Tau. Here, an ascent up a rock wall is organized using a 20-meter rope in a sports climbing manner. The path then transitions onto the right-bank lateral moraine of the Zvezdochka Glacier, lying on the slopes of Ak-Tau.

About half an hour's walk from the rock wall, the lateral moraine becomes gentle, and a tent camp can be set up here. This was where the first intermediate camp, at 4700 m, was established.

Features of the 4700 m camp:

- On a sunny day, it is significantly warmer here than at the base camp (4100 m) due to intense heating of the rocky slope.

- There is almost always a small lake with good drinking water at the 4700 m camp.

- The ascent from the 4100 m camp to the 4700 m camp typically takes 4-5 hours.

To reach the foot of Peak Pobeda from the 4700 m camp, one needs to cross the Zvezdochka Glacier, which is about two kilometers wide here. The glacier is almost horizontal, with few and narrow crevices.

The main obstacles are:

- a wide stream flowing across the glacier in a depression directly under the slopes of Peak Pobeda;

- and usually a deep layer of freshly fallen, loose snow on the glacier surface.

Crossing the glacier takes from one to four hours, depending on the surface conditions.

Despite the complexity and duration of the approaches, the slopes of Peak Pobeda have been visited by mountaineering expeditions several times. However, all attempts at ascent have been unsuccessful, and this premier peak remained unconquered.

In 1938, an expedition led by A. A. Letavet, organized by the All-Union Committee for Physical Culture and Sports, worked in the area with the aim of ascending to the highest point. The expedition's assault group, consisting of L. Gutman, E. I. Ivanov, and A. I. Sidorenko, reached an altitude of 6930 m (by aneroid) in dense fog. The shoulder they reached was named "Peak of the 20th Anniversary of the Komsomol".

In 1943, a topographic expedition led by P. I. Rapasov, working in the Khan-Tengri area, precisely determined the height of the peak to be 7439 m through instrumental survey, and this second-highest peak in the USSR was named Peak Pobeda.

In 1949, an expedition from the Kazakh Alpine Club, led by E. M. Kolokolnikov, attempted a new ascent of Peak Pobeda via the northern slope. The climbers were caught in an avalanche at an altitude of about 5500 m and were forced to abandon the ascent.

In 1955, two well-equipped expeditions simultaneously attempted to ascend Peak Pobeda via different routes.

- The expedition of the Turkestan Military District, led by V. I. Rachek, stormed the peak via the northern slope. A group from this expedition reached a glacier fall at an altitude of about 6500 m. The work of this expedition was curtailed due to bad weather and an accident in the assault group of the second expedition.

- The expedition of the Caucasus Alpine Club, led by E. M. Kolokolnikov, attempted to ascend Peak Pobeda from the Chon-Tareng pass. The assault group, consisting of 12 people, led by V. P. Shipilov, reached an altitude of 6800 m, almost reaching the Eastern Peak. Here, the group was thrown back by severe weather and suffered an accident, resulting in the deaths of 11 people.

During rescue operations, a group led by K. K. Kuzmin from the team of E. A. Beletsky ascended along the ridge from the Chon-Tareng pass to the last camp of V. P. Shipilov's group.

All expeditions that visited Peak Pobeda noted the extremely harsh climatic conditions in the area. According to statistical data provided by M. E. Grudzinsky, during the summer months, around 20 days per month are characterized by:

- overcast weather;

- heavy snowfall;

- strong winds, especially at higher altitudes.

The large amount of snow falling on the steep slopes of the massif makes them highly avalanche-prone. The snowfall at low temperatures results in an exceptionally loose and powdery snow cover, which has led to the specific term "Tian Shan snow". At higher altitudes, the snow becomes compact and firm under the influence of wind, typically only after two to three days of clear, windy weather following a snowfall.

However, with a clear predominance of inclement weather, this snow compaction occurs relatively rarely, making it nearly impossible to expect firm snow throughout the path of a multi-day ascent. It is also worth noting that the deposition of deep fresh snow on a wind-hardened surface significantly increases the avalanche danger on the slopes.

Significant difficulties arise due to the high absolute altitude of the peak. The sharp decline in human performance at high altitudes requires a carefully planned and prolonged acclimatization and training.

Finally, the necessity of prolonged stays at high altitudes while maintaining performance in conditions of very low temperatures (minus 20-25 °C) and strong winds places high demands on the organization of bivouacs, the quality of equipment, and nutrition.

All this requires highly advanced techniques and well-thought-out tactics for the ascent.

The main objective of the joint expedition of the Spartak society and the Kazakh Alpine Club, conducted in the summer of 1956, was to achieve the ascent of Peak Pobeda via the northern slope.

In addition to this, the expedition was tasked with other objectives. It was considered important and interesting to:

- conduct a cycle of meteorological and climatic observations in the area of Peak Pobeda;

- capture the most interesting moments of the expedition's penetration into the depths of the country's lesser-known region on film;

- conduct a thorough examination of the physiological impact of high altitude on the climber's body in connection with the prolonged stay of a large team of mountaineers in high-altitude conditions.

This report is dedicated to the description of the solution to the first of these tasks - the ascent of Peak Pobeda.

The results of the climatic observations will be published by their authors, A. M. Borovikov and M. E. Grudzinsky, in specialized literature. The results of the physiological examination of the impact of altitude on the human body are part of N. A. Gadzhiev's dissertation. The film crew of the expedition is currently preparing a film dedicated to the expedition's work.

II. Preparation for the Ascent

A. Base Camp and its Organization

As noted above, the expedition's base camp was located at an altitude of about 4100 m, on the moraine of the Inylchek Glacier, near the confluence of the Zvezdochka Glacier and not far from the foot of the Diky ridge.

The expedition arrived at the base camp site on the morning of August 25, 1956. A caravan of 50 pack horses delivered the main supply of equipment, fuel, and a 15-day supply of food during this trip. The base camp was largely set up on August 25-26. A second trip by a caravan of 30 pack horses delivered about two tons of food to the base camp on August 7. These two trips largely ensured the expedition had everything necessary for its work. Additionally, as needed, sheep were periodically driven to the camp from the transshipment bases mentioned above (so that there was always fresh meat), and additional equipment, fuel, fresh vegetables, and fruits were delivered by pack animals.

Expedition members were accommodated two to three people per tent in "Pamirka" tents and half-tents. In addition to the living tents, two large tent pavilions were set up.

One of them housed the kitchen, equipped with gas stoves; liquefied gas (propane) was delivered to the camp in cylinders by pack animals.

The second tent served as a dining room, club, and storage, and on cloudy days, it also served as a workshop where tasks such as shoe soling and equipment repair were carried out.

Additionally, two Pamirka tents were allocated for housing radio stations, one for a medical station, and one for a photo and film laboratory.

Half a kilometer from the base camp, on the Inylchek Glacier, M. E. Grudzinsky and A. M. Borovikov set up a meteorological station. Meteorological observations were regularly transmitted at set times via radio to Alma-Ata.

The base camp had regular two-way radio communication with Przhevalsk, Alma-Ata, and Frunze, as well as with our transshipment bases at Chon-Tash and at the end of the motorable road, where radio operators and logistics personnel remained.

Furthermore, as necessary, two-way radio communication was established with mobile teams of the expedition working in the upper reaches of the Zvezdochka Glacier and on the slopes of Peak Pobeda using ultra-shortwave radio stations.

For this purpose, observation posts were established:

- on the Zvezdochka Glacier, 0.5 km from the base camp;

- and under the slopes of the Ak-Tau spur, on the lateral moraine of the Zvezdochka Glacier, at an altitude of 4700 m.

B. Reconnaissance, Training, Acclimatization, and Establishment of Intermediate Camps at 4700, 5300, 5800, and 6200 m

During the organization of the expedition, its leadership had the opportunity to thoroughly study the materials of previous expeditions by reviewing their reports and engaging in personal discussions with several of their participants. The expedition leader, V. M. Abalakov, had participated in the assault on Khan-Tengri in 1936, located in the immediate vicinity of Peak Pobeda.

As a result, the approach routes to the peak, the nature of its slopes, climatic conditions, etc., were known in detail. This allowed for the development of a carefully considered plan of action for the expedition even before departing for the mountains, outlining the tactics and timeline for the ascent, preparing the necessary equipment, etc., and devising a training scheme, acclimatization plan, supply drops, organization of intermediate camps, and communication between the assault and support groups, etc.

The extensive experience of the expedition's leadership and participants led to the plan remaining largely unchanged throughout the ascent.

This did not preclude the necessity of conducting thorough reconnaissance on site. Reconnaissance was carried out:

- during the approaches;

- during preparation for the assault;

- during the assault;

- and even during the descent from the summit.

Reconnaissance was always conducted under the guidance and with the personal participation of the expedition leader, V. M. Abalakov.

During the approaches, a reconnaissance group preceded the main column at a distance of a day's or half-day's travel, choosing the path and leaving information about the route in notes placed in cairns established at key points along the route.

The ford across the Sary-Dzhas River was reconnoitered by a special equestrian group a few days before the main forces of the expedition arrived.

After establishing the base camp, a detailed reconnaissance of the path to the slopes of Peak Pobeda along the Zvezdochka Glacier was conducted, and observations on the nature, characteristics, and condition of the peak's slopes were carried out over several days. At this stage, reconnaissance was combined with the establishment of a tent camp at 4700 m on the lateral moraine of the Zvezdochka Glacier, under the slopes of the Ak-Tau spur.

The first reconnaissance group departed on July 27. The group, consisting of Abalakov, Usenov, Gusak, Filimonov, Leonov, Tur, Kletsko, Kuderin, and Agranovsky, crossed the Zvezdochka Glacier, moving along the median moraine, overcame the glacier fall on the turn of the Zvezdochka Glacier at the slopes of Ak-Tau, having deployed 20-meter ropes on the rock wall, and reached the site of the 4700 m camp. On the same day, the group, consisting of Abalakov, Usenov, and Gusak, crossed the Zvezdochka Glacier from the 4700 m camp to the slopes of Peak Pobeda and marked the most appropriate route along the glacier. Red flags were used to mark the path.

On the evening of July 27, and throughout July 28, when another 12 people arrived with cargo, and on the morning of July 29, constant observation of the slopes of Peak Pobeda was conducted. The structure of the slopes and, particularly, the paths of avalanches and their timing were studied in detail using a 10x binocular and a 50x spyglass. These observations allowed for the planning of the general direction of the ascent route.

The route along the counterfort on the northern wall of Peak Pobeda, previously considered in Moscow, was selected, and the locations of the intermediate camps at 5300 m (on a snow saddle, at the right part of the triangle) and 5800 m (on the ridge of the counterfort, 30-40 m below a characteristic large snow cornice, in a wind-protected area) were identified on the ground. Both camps were planned to be established in snow caves.

On July 29, the reconnaissance group descended to the base camp.

On July 31, a group consisting of Abalakov, Filimonov, Gusak, Leonov, Tur, and Usenov departed from the base camp to the 4700 m camp, with the goal of laying a path up the slope of Peak Pobeda and establishing camps at 5300 m and 5800 m, and reached the slope of Peak Pobeda. However, the group was forced to return to the 4700 m camp due to bad weather. On August 1 at 15:30, a group consisting of Kizel, Arkin, Budanov, Lapshenkov, Kletsko, Agranovsky, Kuderin, Musaev, Zubkov, Zakhvatov, Anufrikov, and Pustovalov arrived, delivering about 150 kg of cargo. At the 4700 m camp, 5 large assault tents with double walls were set up, and necessary technical equipment, including pitons, ropes, avalanche shovels, sleeping bags, fuel, etc., as well as some food, was concentrated.

Due to prolonged bad weather, the departure to the future 5300 m camp did not occur, and on August 3, a group of 14 people descended to the base camp.

A reconnaissance group consisting of Abalakov, Filimonov, Gusak, Anufrikov, and two cameramen stayed at the 4700 m camp from July 31 to August 5, 1956, observing the peak's slopes in bad weather. This allowed for the identification of additional features and the finalization of the ascent route to the 5300 m camp, safe from avalanches. On the morning of August 5, the group descended to the base camp.

Detailed reconnaissance of the path along the slopes of Peak Pobeda was further conducted during the establishment of intermediate camps at 5300 m, 5800 m, and 6200 m.

On August 8 at 6:15 AM, a group consisting of Abalakov, Filimonov, Gusak, and Budanov departed from the base camp, arrived at the 4700 m camp at 10:15, crossed the Zvezdochka Glacier, and spent the night under the slopes of Peak Pobeda. On the evening of the same day, the duo Abalakov - Filimonov laid a trail 150 m up from the overnight spot.

On August 9, the group ascended to a saddle, chose and trod a path between crevices, and spent the night in a tent on the northern edge of the saddle. On August 10, the group crossed the saddle, chose a site for a snow cave at 5300 m, and began constructing the cave for 15 people. By mid-day, a group led by Kizel arrived, delivering 200 kg of food, and descended to the 4700 m camp after 2-3 hours. By evening, the cave was completed, and the reconnaissance group spent the night there.

On August 11, the duo Abalakov - Filimonov laid a trail from the 5300 m camp to the base of a cornice on the ridge of the counterfort and, after thoroughly probing the snow, selected a site for a snow cave at "5800 m". On the steep glaciated section of the ascent to the ridge, ropes were secured, and steps were cut into the ice. Ice and rock pitons were driven for safety. Laying the path upwards took 9 hours, and descending along the prepared tracks took 2 hours and 15 minutes.

On the same day:

- The duo Budanov - Gusak worked on expanding the 5300 m cave.

- A group led by V. A. Kizel arrived at the 5300 m camp from the 4700 m camp, delivering 150 kg of equipment and food.

On August 12, the entire group, carrying 17-20 kg rucksacks, ascended from 5300 m to 5800 m along the prepared path. The ascent took 4 hours and 15 minutes.

The group, consisting of Arkin, Kletsko, Gusak, Budanov, Usenov, and Musaev, began constructing the 5800 m cave, which was fully ready by evening.

The duo Abalakov - Filimonov:

- laid the path of ascent to the cornice;

- organized piton protection and hung ropes;

- inspected the path to the glacier fall along the counterfort.

The rest of the participants descended through the 4700 m camp to the base camp.

On August 13 at 11:00 AM, in fog and light snowfall, a group consisting of Abalakov, Filimonov, Kletsko, Arkin, Musaev, Usenov, Budanov, and Gusak departed to establish the next camp, each carrying 10 kg of useful cargo. The reconnaissance duo Abalakov - Filimonov led the group, advancing 1-1.5 hours ahead. In deep snow, with strong winds and drifting snow, a camp was established at an altitude of 6200 m, on a gentle part of the counterfort. A cave for 8 people was roughly excavated (without smoothing the ceiling, floor, or digging a trench in front of the entrance), with a niche for storage. At 17:00, the group began descending to the 5800 m cave, where they spent the night.

On August 14, at 7:00 AM, the group of eight began descending in thick fog and drifting snow and reached the base camp by evening.

This sortie fully accomplished the plan of preliminary reconnaissance, supply drops, establishment of camps, and path laying up to 6200 m.

Reconnaissance and path laying above 6200 m were carried out directly during the assault. They were conducted by the duo Abalakov - Filimonov or Abalakov - Gusak, who went 1-1.5 hours ahead of the main group during the general movement and advanced further upwards during cave construction.

Thus, the main part of the group was able to move along a fully prepared path - along ready-made tracks, using pitons and ropes previously secured on hazardous sections.

The training and acclimatization system implemented by the expedition deserves a brief characterization. The nature of the training changed significantly over time and can be divided into five stages:

- General training before departing for the mountains - from the winter of 1955-1956 to mid-June 1956. Training included winter skiing, and spring and summer cross-country running with sprinting.

- A training camp at Koi-Sara on the shores of Lake Issyk-Kul, at an altitude of 1800 m, lasting 12 days.

- Training primarily on endurance during the approaches (July 17-25).

- Training and acclimatization during the establishment of the base camp and camps at 4700 m, 5300 m, 5800 m, and 6200 m.

- Acclimatization during the assault.

The preliminary training camps practiced by the Spartak team during 1955-1956 were particularly effective. These camps were held at a sufficient altitude (around 1500-2000 m) and aimed at:

- active rest for team members before the intense load during the approaches and ascent;

- conducting diverse specialized training.

Such camps are similar to directed preliminary training in other sports before major competitions and are especially beneficial for non-professional athletes burdened with significant professional work during the year.

The applied training scheme proved fully justified. Participants arrived at the base camp in excellent physical condition, with strengthened nervous systems, and practically did not "feel" the altitude either at the base camp (4100 m) or at the camps at 4700 m and 5300 m.

During the establishment of intermediate camps at 4700 m, 5300 m, 5800 m, and 6200 m, as well as during the assault itself, active high-altitude acclimatization was carried out simultaneously. This was achieved through periodic ascents with relatively light loads (10-15, sometimes 17-25 kg) to gradually increasing altitudes, participation in intense physical work such as cave digging, overnight stays at the achieved altitude, and subsequent descents to previously освоited altitudes.

The duration of rest at освоited altitudes was chosen to ensure the most complete recovery of strength. All measures were taken to organize calm rest. For this purpose, overnight stays were organized in sufficiently spacious, well-equipped caves, abundantly supplied with warm clothing - down sleeping bags, foam inserts, etc. The caves excellently protected participants from wind and low temperatures - to a much greater extent than tent accommodations.

Particular attention was paid to ensuring participants had an unlimited supply of drinking water at high altitudes - in the form of tea, compotes, kissels, coffee, etc., with abundant high-quality nutrition.

We believe that the main principles of the applied training system:

- speed training in winter, spring, and summer;

- preliminary training camp at a relatively low but sufficient altitude by the world's water body with cool water;

- abundant, vitamin-enriched nutrition;

- alternating prolonged loads with complete rest, etc. - are worthy of attention and can be applied to other sports.

III. Safety Measures

A. Support Group and its Work

During the assault, a strong support group was stationed below, at the base camp, to monitor the assault group and maintain communication with it. The support group was led by the assistant expedition leader, Honored Master of Sports A. M. Borovikov. The group included climbers:

- Avdeev;

- Agranovsky;

- Anufrikov;

- Grudzinsky;

- Zakhvatov;

- Zubkov;

- Kelver;

- Kuderin;

- Polyakov;

- doctor Gadzhiev;

- radio operators Moskalyov and Tolokin.

To monitor and communicate with the assault group, the support group established an observation camp on the moraine of the Zvezdochka Glacier, from which the entire path from the foot to the summit was visible. For observation, they used:

- a 10x binocular;

- a 50x spyglass.

Communication with the assault group was carried out through two channels. At 20:30 daily, radio communication was conducted using ultra-shortwave radio stations. Thanks to this, the support group was able to know the exact position and intentions of the assault group.

It is particularly worth noting that radio communication was used to transmit weather forecasts to the assault group, specially prepared for the Peak Pobeda area in Alma-Ata. These forecasts, used in addition to general meteorological information and daily weather observations on the Inylchek Glacier, proved to be very accurate and greatly assisted the assault group in planning its activities. The assault group always knew the forthcoming weather for 3-4 days ahead.

In addition to radio communication, light signaling was carried out using rockets, smoke bombs, and signal matches. A specially developed code allowed for the transmission of information about impending bad weather, in addition to standard signals.

The support group was prepared to immediately assist the assault group if needed. It was also connected by radio to the cities of Przhevalsk, Alma-Ata, and Frunze and could call for help from outside if necessary. The organization of external communication is described above in Section II, A.

Essentially, safety measures also included several preventive measures, such as:

- thorough reconnaissance and path preparation;

- establishment of intermediate camps;

- the training and acclimatization system;

- ensuring that the equipment used was suitable for the task at hand,

as described above.

It is worth noting that the accident-free nature of the expedition was significantly contributed to by the collective leadership. The most important decisions were made after careful discussion by the coaching council, consisting of the most experienced participants.

The coaching council included:

- V. M. Abalakov;

- M. I. Anufrikov;

- Ya. G. Arkin;

- A. M. Borovikov;

- M. E. Grudzinsky;

- N. A. Gusak;

- V. A. Kizel;

- I. P. Leonov;

- A. I. Polyakov;

- L. N. Filimonov;

- doctor N. A. Gadzhiev.

IV. Composition of the Assault Group and Equipment

A. Composition

The assault group consisted of eleven people (in alphabetical order):

- Abalakov V. M.;

- Arkin Ya. G.;

- Budanov P. P.;

- Gusak N. A.;

- Kizel V. A.;

- Kletsko K. V.;

- Leonov I. P.;

- Musaev S.;

- Tur D. A.;

- Usenov U. U.;

- Filimonov L. N.

From the base camp to the 5300 m camp, the assault group was accompanied by M. I. Anufrikov as a cameraman. Above this camp, cinematography was carried out by V. A. Kizel, who had specially prepared for this task.

The distribution among rope teams during the assault changed repeatedly, depending on the tasks being addressed.

B. Equipment

Considering all supply drops and the cargo in rucksacks when departing on the route, the group was fully provided with food and fuel for 22 days.

The personal equipment of each participant included:

- a rich set of high-quality warm clothing, including woolen underwear, woolen trousers and sweaters, down pants and jacket, and a windproof suit;

- down, woolen, canvas, and leather mittens;

- woolen socks, etc.;

- an ice axe or ice axe-ice hammer with a pick-shovel and a long handle;

- high-altitude boots (up to 5300 m) and special "teckelton" boots with long spikes, replacing crampons (above 5300 m).

The public equipment included:

- three four-man down sleeping bags;

- two such single-person bags;

- three assault tents with double walls;

- two "Vdarsky" tents;

- a set of lightweight foam mats;

- five 30-meter nylon ropes;

- five 40-meter nylon cordelettes;

- 30 carabiners;

- 25 ice and 20 rock pitons;

- four wick-type gasoline stoves;

- magnesium signal matches and rockets;

- a first-aid kit with necessary medications and dressings;

- etc.

For constructing snow caves, the group had:

- five avalanche shovels;

- four special duralumin snow saws.

Tov. Anufrikov, and later tov. Kizel, had a handheld movie camera and about 600 m of film stock. The group also had five "Zorkiy" type cameras.

It is worth noting that all equipment and supplies were of domestic production and of very high quality. Several items of equipment (teckelton boots, boots, tents, pitons, avalanche shovels, snow saws, mittens, sleeping bags, backpacks, etc.) were of special design and manufactured to order. Some of the food (200 kg of food concentrates) was also manufactured to order. The role of the deputy expedition leader, Master of Sports A. I. Polyakov, in ensuring the expedition and assault group with everything necessary is particularly noteworthy.

C. Ascent Route

The ascent route can be conditionally divided into six sections. Below, these sections are listed, and their characteristics are given:

Section 1. From the base camp, through the 4700 m camp to the foot of the peak

This section is essentially part of the approach. The path here runs along the glacier