ASCENT DOCUMENT

-

High-altitude ascent category

-

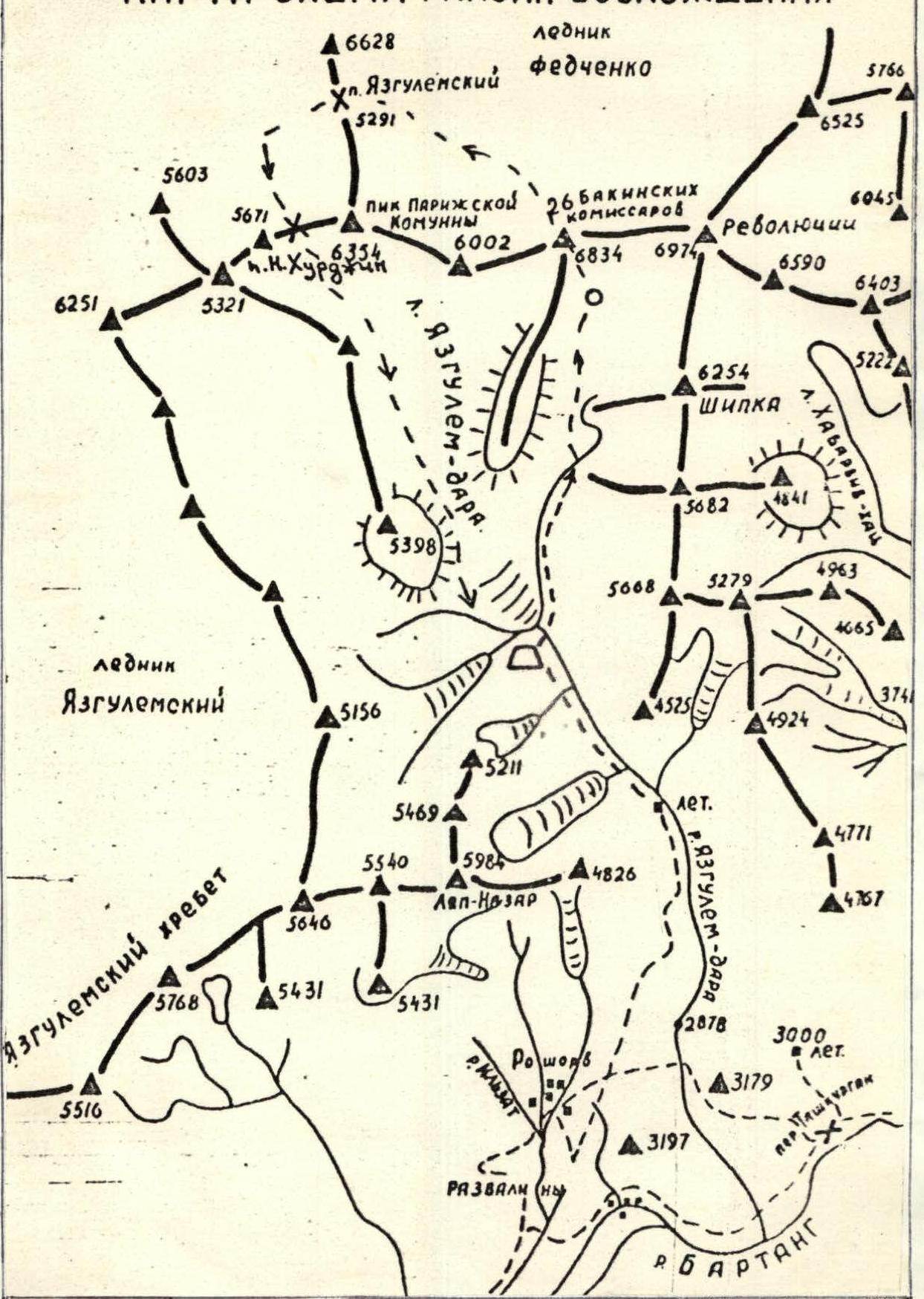

Central Pamir, Yazgulemsky Ridge

-

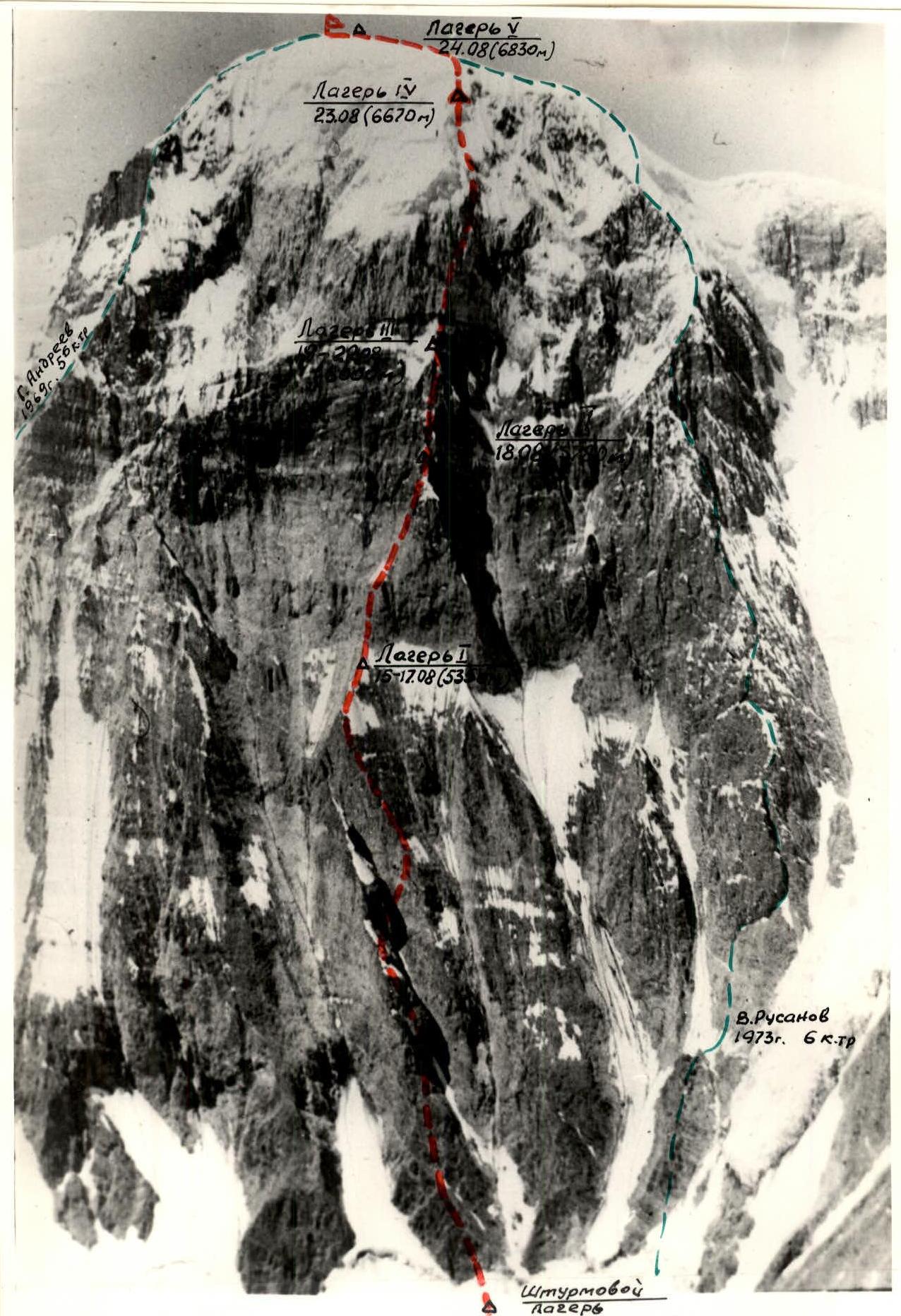

Peak 26 Baku Commissars (6834 m) via the center of the south wall

-

Proposed difficulty category — 6

-

Route characteristics:

Height difference — 2550 m. Length of sections with 5–6 category difficulty — 1690 m. Average wall steepness — 74°

-

Pitons driven:

for belaying — rock 282, ice 52, no bolt pitons; for creating artificial footholds — 59 rock, 2 ice, no bolt pitons

-

Total climbing hours — 113 (including route processing)

-

Number of nights and their characteristics

Total — 10, including 2 bivouacs with sitting positions (5 bivouac sites)

-

Captain's, team members' names, and their sports qualifications

- Shevchenko Yuri Sergeevich — team leader, Master of Sports

- Nosov Anatoly Pavlovich — deputy leader, Master of Sports

- Yaroslavtsev Vladimir Fedorovich — team member, Master of Sports

- Cherepov Vladimir Alekseevich — team member, Master of Sports

- Shimeelis Vladislav Petrovich — team member, Master of Sports

- Parfenenko Valery Semenovich — team member, Candidate for Master of Sports

- Sharonov Boris Pavlovich — team member, Candidate for Master of Sports

-

Team coach — Shevchenko Yuri Sergeevich.

-

Departure date — August 15, 1977 summit date — August 24, return to base camp — August 27, 1977

AREA MAP-SCHEME

- □ — base camp (3800 m)

- О — assault camp

- ---- movement path

I. Brief geographical description and sporting characteristics of the ascent object

Participants of the 1928 Pamir expedition led by N.V. Krylenko were impressed by the majesty of the highest peaks in the Yazgulemsky Ridge. In honor of significant revolutionary events, they were named (from west to east): Peak Paris Commune (6365 m), Peak 26 Commissars (6841 m), Peak Revolution (6945 m)*.

From the north, these peaks have a powerful glaciation and frame a vast firn plateau, giving rise to one of the largest glaciers on Earth — the Fedchenko Glacier. The glaciation of the southern slopes of the Yazgulemsky Ridge is also significant. To the south of Peak Revolution lies a lateral ridge with peaks above 6000 m (Peak Shipka — 6254 m). The southern edge of Peak 26 Commissars transitions into a short, relatively low ridge without significant peaks. Glaciers originating from the pass Nizhny Khurdjin (west of Peak Paris Commune) and from the cirques of Peaks Revolution and 26 Commissars form a significant and difficult-to-traverse Yazgulem-Dara glacier. The Yazgulem-Dara river flows southward and, cutting through a deep canyon, empties into the Bartang river. The lateral spurs of the Yazgulemsky Ridge feature other significant peaks up to 5400–5700 m, presenting alpinistic interest. One of the most notable is Lyap-Nazar peak (5984 m), dominating the kishlak Roshorv, the final point of the automobile road.

Alpinistic exploration of the Peak Revolution area from the south began relatively recently, in 1968, largely due to the enthusiasm of Viktor Pavlovich Nekrasov and army mountaineers. In that and subsequent years, several routes were pioneered: Peak Revolution via the southwest wall (Nekrasov, 1968, 6B category difficulty), traverse of Peaks 26 Commissars — Revolution — Shipka

(Logvinov, 1969, 5B category difficulty), Peak Revolution via the southern ridge (Artyukhin, 1968, 5B category difficulty), and others. Less significant ascents include: Peak Shipka (6254 m), with several routes of 5B category difficulty; Peak Lyap-Nazar (5984 m), notable for its south wall ascent by MVO athletes this year and a northeast wall route by a Donetsk team (1973).

The first ascent of Peak 26 Baku Commissars was made in 1957 from the Fedchenko Glacier by a “Burevestnik” group led by E. Tamm. Upon exploring Peak 26 Commissars, high-class ascents were made via the southern ridge: by an army team (Logvinov, 1969), who traversed to Peaks Revolution and Shipka, and by a Tomsk team (Andreev, 1969). The Tomsk team secured the first place in the USSR championship in the high-altitude technical ascent category.

A spectacular ascent via the south wall was achieved by athletes from Donetsk (Rusanov, 1973, 6 category difficulty, first place in the high-altitude category). Their path lay along the right buttress of the wall, a route that remains unrepeated. Notably, the Donetsk team considered ascending via the center of the wall as an alternative. The renowned Soviet climber Koroblin highly praised this variant, deeming it a climb of the highest sporting class.

What characterizes the south wall of Peak 26 Baku Commissars, particularly its central part? The wall is visible from the base camp. It is striking in size, with a height difference of 2550 m (as measured by an altimeter on the glacier below the wall, showing 4300 m). The wall's steepness increases with altitude. A significant (350–400 m) steep rock triangle stands out in the center, with a steepness of up to 80–85°. A series of walls and a steep snow-ice ridge lead to the upper part, the key to the entire wall. The upper part is framed by a 300–400-meter marble overhang, above which hangs a cap of glittering hanging glaciers. The wall is cut by couloirs with continuous rockfall. Choosing a safe path, especially in the lower and upper parts, is complex, demanding a sound tactical plan and excellent physical and technical preparation from the team.

Climbers ascending Peak 26 Commissars face a challenging descent from the summit. The easiest route, with 5B category difficulty, lies northward through Peak Peredovoy (6200 m) onto the Fedchenko Glacier and then via passes Yazgulemsky and Nizhny Khurdjin (5750 m, 3 category difficulty). This arduous return journey to the base camp takes about 3 days.

II. Ascent conditions in the area (relief, climatic conditions, remoteness)

The relief of the peaks in the area is diverse, with an abundance of sheer, smooth walls. Some resemble massive cuts. The walls of Peaks 26 Commissars, Revolution, and Bulgaria are not uniform; they feature belts of white marble, quartzites, and dark belts of weakly cemented schist. Most peaks, despite their steepness, are composed of very friable rocks, leading to frequent rockfalls. Glaciation is significant, with hanging glaciers sometimes located at heights of 5500–6500 m and above. One of the most powerful, descending from the upper cirque of the three peaks of Revolution, collapses almost regularly (every 3–7 days), sending hundreds (or thousands) of tons of ice onto the Revolution Glacier from a height of about 2000 m. Ice fragments and snow dust cover the glacier for many kilometers, a factor to consider when organizing assault camps and observation points. Powerful icefalls and avalanches also fall onto the glacier from the western slopes of Peak Shipka.

During the expedition months (late July and August), the area typically experiences stable good weather, which can be accompanied by significant wind at high altitudes. The climate is dry and continental, with a significant diurnal temperature range. At heights of 5500–6000 m, temperatures can drop to −15°C even inside tents at night. Signs of winter (in an alpinistic sense) were noted this year at a height of 5900 m as early as August 20 (a sharp drop in night and day temperatures). Some years have seen prolonged periods of bad weather:

- In 1970, for example, bad weather in July–August significantly hindered the “Zenit” expedition, preventing them from undertaking an ascent via the wall of Peak 26 Commissars.

- Precursors to bad weather are typical (cirrus clouds, lenticular clouds) with a west or southwest wind.

- Winds from northern directions accompany stable good weather.

Approach routes to Peaks Revolution, 26 Commissars, and neighboring peaks from the south are very complex, making this one of the most inaccessible areas of the Pamir.

Most expeditions used helicopters to transport goods and people directly to the base camp at the tongue of the Yazgulem-Dara glacier, located at an altitude of 3800 m.

The use of automotive transport was limited due to poor roads, with previous expeditions using it only as far as the Kudarinsky region, from where climbers were transferred to the ascent area by helicopter.

There is a single automobile road starting from the 303rd (or alternatively, the 317th) kilometer of the M-97 highway, beginning after the settlement of Kara-Kul.

The road is challenging, even by Pamir standards, especially beyond 30 km from Kudar, where a series of hairpin turns makes it difficult for vehicles like GAZ-66 to navigate. Similar challenging sections exist before the settlement of Sovnob.

The most difficult stage of the approach lies between Sovnob and the final destination — the kishlak Roshorv.

Notably, the LenVO team was the first in the history of expeditions to reach Roshorv by automobile, disproving the notion that organizing a base camp without a helicopter is impossible.

From Roshorv, a two-day caravan with 25 horses was organized to transport goods to the base camp.

The approach to the wall of Peak 26 Commissars from the base camp takes 5–7 hours and follows the moraines and the Yazgulem-Dara glacier.

A postal point is available in the settlement of Sovnob (telegrams are transmitted via radio to RuShan).

To date, six expeditions have operated in the area. In 1968 and 1969, teams from the Armed Forces, as well as teams from:

- Tomsk in 1969 (based on the Fedchenko Glacier),

- “Zenit” DSO (1970),

- Donetsk Alpine Club “Donbass” (1973),

- Uzbek Fitness and Sports Committee (1976).

In 1977, two expeditions arrived under the southern slopes of Peaks Revolution and 26 Commissars — the “Dzhailyk” alpine camp (by helicopter) and the Armed Forces (by automobile to Roshorv and then by caravan).

III. Team preparation for the ascent. Reconnaissance and acclimatization exits

Choosing the ascent object is a responsible task. The “handwriting” of LenVO team members in recent years has been characterized by pioneering wall ascents (mostly on peaks above 6000 m) via the most complex central part, following the direttissima route. Such ascents require immense volitional and mental strain and judicious tactics.

The team has successfully completed several wall ascents meeting these conditions:

- Peak OGPU (1973)

- Peak Engels (1974)

- Peak Borovikov (1975)

- Peak Marx (1976)

- Peak Mizhigir (“Po kaskadam”, 1977)

The center of the south wall of Peak 26 Commissars is an ideal route for an ascent of this nature: extremely challenging in terms of technique, combined, very extensive (2550 m height difference!), and posing seemingly insurmountable tactical difficulties for the team. The training plan was designed with these factors in mind.

The team's preparation included the following stages:

- Pre-camp training. This consisted of winter training aimed at developing and maintaining overall endurance (mainly cross-country skiing and running) and spring training on rocks. Training sessions were held on rocks in Karelia (Hiitola) and Crimea (Foros, Batiliman). The focus was not only on free climbing but also on rational movement with a double rope, on belays, and ascending with a heavy (15 kg) backpack using the “American” method to reduce the number of times backpacks were pulled up the wall. New equipment was tested (after laboratory trials): soft ladders, small carabiners (for climbing with a double rope), clamps, and hammers of new design, as well as several new profiles of rock pitons (all samples were either developed or proposed for use by team member A.P. Nosov).

- Winter training at Tuyuk-Su and Dgoba, and summer training at the “Bezengi” alpine camp and Armed Forces training in the Fann Mountains. Apart from several 5B category difficulty ascents, as part of the preparation for the championship, the team completed a unique ascent by the north wall of Mizhigir (“po kaskadam”), demanding exceptional mental and physical endurance, flawless movement technique, and adherence to a precise tactical plan. This route is classified as 6B category difficulty.

Before ascending Peak 26 Commissars, the team conducted two reconnaissance and acclimatization exits:

-

I exit (August 4–5, 1977). Route: base camp (3800 m) — Revolution Glacier under the wall of Peak 26 Commissars

Tasks:

- Establishing an assault camp and transporting goods.

- Visual reconnaissance of the wall and route option selection.

- Developing a general tactical ascent plan.

- Acclimatization.

All 12 team members participated in the exit. All tasks were completed.

-

II exit (August 7–11, 1977). Route: base camp (3800 m) — Revolution Glacier. On August 8, 9, and 10, work was done on processing the lower part of the wall.

Tasks:

- Refining the ascent route.

- Processing the lower part of the wall, organizing a bivouac on the wall, and transporting supplies and equipment.

- Acclimatization to a height of 5200 m.

9 team members participated in the exit. All tasks were fully completed.

IV. Organizational and tactical ascent plans. Composition of the assault group. Safety and observation groups.

The organizational plan considered the tight timeframe of the Armed Forces gathering in the Pamir:

- July 25 – 30 — gathering of participants in Osh, logistical support, paperwork, physical fitness tests, etc.

- July 31 – August 2 — transportation by automobile to kishlak Roshorv

- August 3–4 — organizing a caravan and moving to the base camp

- August 4–5 — I reconnaissance and acclimatization exit

- August 7–11 — II acclimatization exit and route processing

- August 15–26 — ascent for the USSR championship

- August 27–28 — return to Osh and conclusion of the expedition.

Thus, only 22 days were allocated for work in the mountains, including prolonged acclimatization and the ascent itself.

As a result of reconnaissance exits and thorough analysis of wall photographs and visual observations, it was decided to adhere to the following tactical principles:

- Process the lower, rockfall-prone part of the wall.

- Process the 350–400-meter key sections (the left edge of the large triangle, the marble overhang). For this, bring a corresponding reserve of rope on the ascent.

- Choose bivouac locations (starting points for processing) that are not only safe but also, if possible, have lying-down positions (on snow-ice ridges 60–100 m from the walls, particularly from the marble belt, where massive icicles, 5–8 m long, can fall).

- Move from one good bivouac site to another planned site in a day (regardless of the number of days spent on processing). Thus, the principle of stopping “wherever night catches” was rejected, and the presence of unprepared (hanging) and potentially unsafe bivouacs was practically eliminated. The time spent on organizing bivouacs was undoubtedly compensated by good rest over several nights.

- Divide participants into two subgroups: the leading (at least 2 ropes) and the supporting group. The latter was tasked with uninterrupted supply of equipment and provisions. The supporting subgroup worked using the “shuttle” method.

- Ascend the marble overhang not “head-on” but by deviating upwards to the right “along the arrow” towards the right part of the ice cap, thus avoiding prolonged work under the cap. Careful observation led to the conclusion that the probability of ice or avalanches falling from the cap was very low (late season, minimal ice front fragmentation, and other signs of a stable state).

The team's well-being was ensured by other measures as well. A qualified safety group (6 people) was created to insure the team “from below” until they passed the large triangle of the wall. Then, the safety group was to ascend Peak 26 Commissars via the western ridge and meet the team at the summit. The single descent route (to the Fedchenko Glacier) guaranteed that the two groups (13 people) could provide assistance if needed.

As evident from the plan, the team's tactics were based on principles ensuring safety and reliability of the ascent.

The observation group, consisting of 5 people led by Master of Sports I.B. Karpov, conducted visual observation from the area of Lake Teploe (using 12x binoculars) and maintained radio communication on VHF radios. Radio communication was conducted at 8:30 and 19:00, with listening sessions at 12:00, 15:00, and 17:00. The emergency signal was a red flare. The communication, observation, and interaction plan also included meeting the groups near the summit and a joint descent, as well as a backup communication method in case the radios failed.

Movement specifics:

- The team leader climbed without a backpack (or with a light backpack).

- Even at heights of 5700–6400 m, some leading climbers (V.F. Yaroslavtsev) preferred to climb complex rocks in galoshes.

- Forward pairs processing the route regularly changed.

Composition of the assault group:

-

- Shevchenko Yu.S. — MS, captain and coach

-

- Nosov A.P. — MS, deputy captain

-

- Yaroslavtsev V.F. — MS, team member

-

- Cherepov V.A. — MS, team member

-

- Shimeelis V.P. — MS, team member

-

- Parfenenko V.S. — CMS, team member

-

- Sharonov B.P. — CMS, team member

The core of the team consisted of the 1976 champions in the high-altitude category (Shevchenko, Nosov, Cherepov, Shimeelis). Other team members were relatively “new”; Sharonov, for example, was listed for the championship and participated in processing the wall of Peak Marx in 1976, while Parfenenko was part of the group in several ascents over the past 5–6 years and this year (like Yaroslavtsev) completed the “cascades” of Mizhigir with us.

In addition to the listed individuals, the following participated in the team's work:

- Baev A.K. (CMS)

- Gorodetsky V.I. (1st sports category)

- Ortin A. (1st sports category)

- Sobolev N.M. (1st sports category)

- Vashenyuk E.V. (1st sports category)

All were included in the championship application.

The safety group consisted of:

-

- Ortin A. — 1st sports category, leader

-

- Baev A.K. — CMS, team member

-

- Gorodetsky V.I. — 1st sports category

-

- Sobolev N.M. — 1st sports category, team member

-

- Vashenyuk E.V. — 1st sports category

-

- Ugarov V.A. — 1st sports category

The observation and communication group consisted of 6 people (leader — Master of Sports I.B. Karpov).

X. Route passage order

Recall that the lower, most rockfall-prone part of the wall was processed by the team during the II acclimatization exit (August 8–10). 1100 m of ropes were laid.

August 14. The familiar but still difficult path from the base camp to the bivouac under the wall took 5 hours and 30 minutes.

August 15. Departure at 8:00. On the glacier, it was very cold before sunrise. We quickly traversed the path along the glacier and the avalanche cone (section R0–R1). We climbed into a powerful randkluft (section R1–R2) and from there followed endless belays upwards: through iced walls of the randkluft, walls of 8–12 m, crossing several gullies and internally angled rock formations (section R2–R3) — potential paths for rockfalls. We moved from one shelter to another. We encountered a series of vertical walls, totaling 330 m (section R3–R4), with the most complex parts of this path. The rock was like sandstone or schist, as if sprinkled with cement dust. Steepness reached 85–90°. At the end of the section, there was a 40-meter ascent with a cornice (overhang about 1 meter). Using ladders, we climbed onto the cornice. After two ropes, we followed a wide internal angle to the crest of the counterfort (section R4–R5) and along it (sections R5–R6 and R6–R7) to a powerful rock tower. From its upper edges hung unprecedented 5–10-meter icicles. We bypassed the tower on the right via very complex wet or iced slabs. In a gully-depression (best passed when not in sunlight!), we drove rock and screwed in ice-tube pitons (10 pieces, section R7–R8). The next section (R8–R9) included very difficult 6-category complexity sections, especially since the rocks were very fragile and the average steepness was 85°. After a long section of rocky ridge (section R9–R10) and an ice slope with calgaspores (section R10–R11), we finally reached camp I at 18:00. 100 m below, the route processing was completed (August 8–10). The safe location (ice ridge) was chosen. With great effort, we organized the camp in 3 hours, where we stayed on August 16 and 17.

Throughout the first day of ascent (and processing days), rockfalls continuously roared through neighboring gullies, especially to the left, but the route was surprisingly quiet. Only between 9:00 and 10:00 was there a fall of icicles noted.

August 16–17. On the night of August 16, bad weather struck. A stormy wind blew, and up to 10 cm of snow fell overnight. Despite the steepness of the “big triangle” below us, snow covered ledges, small footholds, etc., significantly complicating the route. The weather improved by morning, but it was windy and very cold. To the left, along a wide gully, powder snow avalanches descended. The temperature inside the tent at night was −10°C. Despite this, on August 16, sections R11–R12 and R12–R13 were processed, totaling 200 m. On August 17, when it warmed up and snow melted in many places, the remaining part of the “triangle” wall was processed — 250 m with an average steepness of 85° (section R14–R15). Some overhanging sections required artificial footholds (8 pitons). The complexity of the section was 6B category difficulty.

August 18. Sections from R11–R12 to R14–R15 were traversed using belays, including 3 overhangs of 12–15 m with a steepness of 95°. The “triangle” took a day of intense work to overcome (despite preliminary processing on August 16–17). We stopped on a snow-ice ridge (section R15–R16) above the quartzite belt (clearly visible at the top of the “triangle”). Sitting bivouacs were organized, which took 3 hours of tiring work to carve out of ice and rocks.

August 19. The route segment from the top of the “triangle” to the marble overhang was traversed without preliminary processing. Section R16–R17 is a 200-meter rocky ridge-wall, particularly challenging at the top where sheer slabs turn into an overhang. Here, one of the few places with solid rock, despite the difficulty (6B category), was somewhat enjoyable. After this, we reached a knife-edge ice ridge with cornices. Here, 80 m from the marble wall (section R17–R18), after prolonged work (4 hours!), lying-down platforms were carved out, where we stayed from August 20 to 22 (camp 3). The most challenging part — the marble belt — was yet to be processed. Not only was there a lack of bivouac sites on the belt except for hanging ones, but the нависающaя ice cap made it difficult to assess their safety (except under cornices).

August 20–22. On the night of August 20, bad weather struck again, with about 10 cm of snow and a sharp drop in temperature (overnight temperature inside the tent was −16°C). On August 20, the Nosov-Yaroslavtsev pair managed to process 35 m of the wall's beginning (section R18–R19) in 5 hours. This was an overhanging wall ending in a 2.5-meter cornice. The rock was like sandstone. In some places, steps were chiseled with hammers for footholds.

On August 21, 130 m of the vertical marble wall (section R19–R20) and another 40 m of the overhanging wall (section R20–R21) were processed. Free climbing... in galoshes at an altitude of 6100 m. Above us was the ice cap of Peak 26 Commissars. On August 22, processing continued. The challenges persisted:

- from section R22–R23 — overhanging slabs;

- from section R26–R27 — rocks with sections of ice and snow.

The last section is located at the end of the so-called “arrow” and crowns the marble wall. A total of 360 m of rope was laid. Now, this key section of the route could be passed reliably and quickly.

August 23. A very tiring day. We traversed to section R27–R28. Further, the path lay along the right part of the ice cap. Here, on very steep (appearing sheer!) ice ridges, we encountered ice and high-altitude powder snow. We had to dig a trench. Choosing a safe path was very challenging. We crossed two avalanche gullies.

The late season and low temperatures largely mitigated the risks on this section. We stopped for a sitting bivouac in the dark.

August 24. Along a steep (60°) slope of the ice cap (section R28–R29), we reached the summit ridge of Peak 26 Baku Commissars. In cloudy weather, with snowfall, we ascended to the summit dome via a simple ridge (with cornices!). The cairn is located below, in the rocks of the northern ridge. We found a note from Yu. Sitchikhin's group (“Trud”, Chelyabinsk, 1976), who ascended from the Fedchenko Glacier.

August 25. In the morning, we met the safety group on the summit, who had ascended via the western ridge. Over three days (August 25–27), we descended along the northern edge to the Fedchenko Glacier and, via the Yazgulemsky and Nizhny Khurdjin passes, returned to the base camp, satisfied with our victory over the Pamir giant.

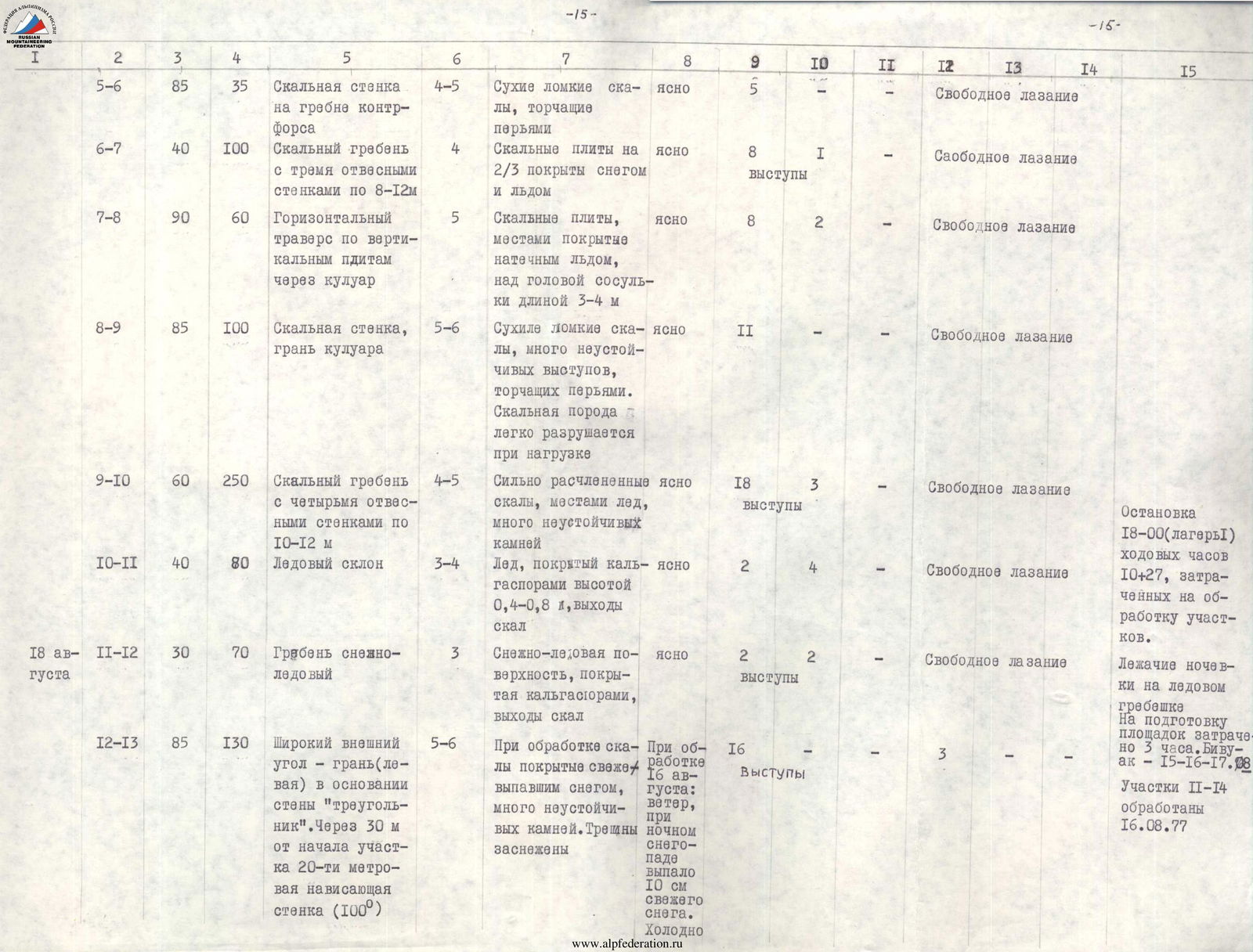

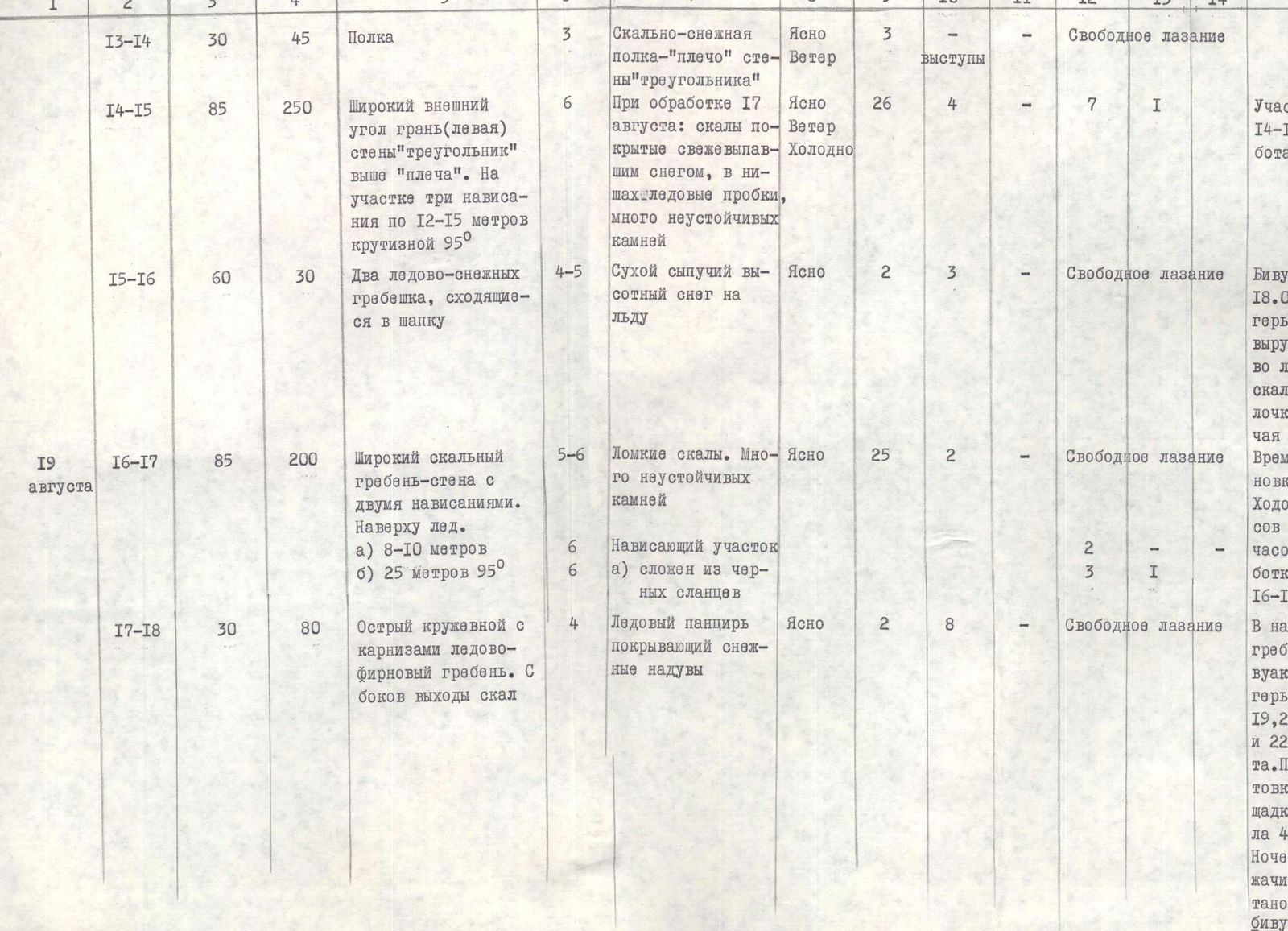

TABLE OF MAIN ROUTE CHARACTERISTICS

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| August 15, 1977 | R0–R1 | 30 | 50 | Avalanche cone | 3 | Firn, ice | Clear | 1 | 1 | — | Free climbing | — | — | Departure 8:00, sections R0–R3 processed on August 8 (see Route Passage Order) |

| R1–R2 | 85 | 30 | Rocky wall of randkluft | 4 | Wet rocks | Clear | 4 | — | — | Free climbing | — | — | ||

| R2–R3 | 45 | 180 | Wide internal angle | 4 | Rock slabs with many unstable stones | Clear | 12 | — | — | Free climbing | — | — | ||

| R3–R4 | 85–90 | 330 | Rock wall with two overhangs: a) 30 m – 95° b) 40 m – 95°. Section b) ends with a rocky cornice with an overhang of 0.8–1.0 m | 5–6 | Dry rocks, fragile like sandstone and schist with crumbling holds and destructive cracks when driving pitons. Pitons easily removable from their sockets after being driven | Clear | 31 | — | — | Free climbing | — | Section R3–R4 processed on August 9 | ||

| R4–R5 | 60 | 70 | Wide internal angle leading to the counterfort crest | 4–5 | Rock slabs, some with ice. Many unstable stones, fragile rock | Clear | 6 | 2 | — | Free climbing | — | Sections R4–R9 processed on August 10 | ||

| R5–R6 | 85 | 35 | Rocky wall on the counterfort crest | 4–5 | Dry, fragile rocks, protruding like feathers | Clear | 5 | — | — | Free climbing | — | — | ||

| R6–R7 | 40 | 100 | Rocky ridge with three sheer walls, 8–12 m each | 4 | Rock slabs, 2/3 covered in snow and ice | Clear | 8 | 1 | — | Free climbing | — | — | ||

| R7–R8 | 90 | 60 | Horizontal traverse across vertical slabs through a gully | 5 | Rock slabs, some with ice, icicles 3–4 m long hanging above | Clear | 8 | 2 | — | Free climbing | — | — | ||

| R8–R9 | 85 | 100 | Rocky wall, edge of a gully | 5–6 | Dry, fragile rocks, many unstable protrusions. Rock easily destroyed under load | Clear | 11 | — | — | Free climbing | — | — | ||

| R9–R10 | 60 | 250 | Rocky ridge with four sheer walls, 10–12 m each | 4–5 | Heavily dissected rocks, some ice, many unstable stones | Clear | 18 | 3 | — | Free climbing | — | — | Stop at 18:00 (camp I), total climbing hours 10 + 21 hours processing. Lying-down bivouacs on an ice ridge. Preparation of platforms took 3 hours. Bivouac August 15–17. | |

| R10–R11 | 40 | 80 | Ice slope | 3–4 | Ice covered in calgaspores 0.4–0.8 m high, rock outcrops | Clear | 2 | 4 | — | Free climbing | — | — | ||

| August 18 | R11–R12 | 30 | 70 | Snow-ice ridge | 3 | Snow-ice surface covered in calgaspores, rock outcrops | Clear | 2 | 2 | — | Free climbing | — | Sections R11–R14 processed on August 16 | |

| R12–R13 | 85 | 130 | Wide external angle — edge (left) at the base of the “triangle” wall. After 30 m, a 20-meter overhanging wall (100°) | 5–6 | Rocks covered in fresh snow during processing, many unstable stones. Snow-filled cracks | During processing on August 16: wind, 10 cm of fresh snow fell during the night. Cold | 16 | — | — | Free climbing | — | — | ||

| R13–R14 | 30 | 45 | Ledge | 3 | Rock-snow ledge — “shoulder” of the “triangle” wall | Clear, windy | 3 | — | — | Free climbing | — | — | ||

| R14–R15 | 85 | 250 | Wide external angle, edge (left) of the “triangle” wall above the “shoulder”. Three overhangs, 12–15 m, 95° steepness | 6 | Rocks covered in fresh snow during processing on August 17, trace plugs in niches, many unstable stones | Clear, cold | 26 | 4 | — | Free climbing | — | Section R14–R15 processed on August 17 | ||

| R15–R16 | 60 | 30 | Two ice-snow ridges converging into a cap | 4–5 | Dry, powdery high-altitude snow on ice | Clear | 2 | 3 | — | Free climbing | — | — | Bivouac on August 18 (camp 2). Sitting bivouac on a platform carved in ice and rocks. Stop time 20:00. Climbing hours 12 – 14 hours processing on August 16–17. | |

| August 19 | R16–R17 | 85 | 200 | Wide rocky ridge-wall with two overhangs. Ice at the top. a) 8–10 m b) 25 m, 95° | 5–6 | Fragile rocks. Many unstable stones | Clear | 25 | 2 | — | Free climbing | — |