Report

On the first ascent of the eastern ridge of Peak Pamyati Zhertv Tetnulda (5746 m) (Moscow Pravda) in the southwestern Pamir, approximately 4B–6 category of difficulty, made by a group of participants of the Donetsk Climbing Competition for the championship of the Ukrainian SSR in 1967 in the class of high-altitude technically complex ascents. Donetsk 1967

I. Geographical location and sports characteristics

The area of Peaks Marx and Engels is located within the Gorno-Badakhshan Autonomous Region of the Tajik SSR, in the southwestern Pamir, within the geographical coordinates: 37°02′–37°06′ north latitude and 72°29′–72°32′ east longitude. Climbers began to explore this area relatively recently compared to other regions of the Pamir and Tian Shan. Only in 1954 did an expedition from the Georgian Alpine Club arrive here. They were the first to ascend several peaks in the area, including the highest point – Peak Karl Marx (6726 m) from the south (from the East Nishghar glacier), and the third highest peak – Peak Friedrich Engels (6510 m) from the south (from the Kishty-Dzherob glacier).

The high (over 6000 m) ridge from Peak Leningrad State University to Peak Marx drops steeply to the east into the Zurgvand valley, forming a nearly vertical wall about 8 km long. The northeastern walls of Peaks Marx and Engels (to the right of the Kustovsky route, beyond the bend of the wall) can evoke admiration for their inaccessibility among any master of wall climbing. Therefore, with the recent introduction of a new class – high-altitude technically complex ascents – in the USSR championships, societies, and departments on mountaineering, this area became very popular and will likely remain a pilgrimage site for many climbing groups for a long time.

In 1964, the Spartak Central Council Climbing Competition was held here, and in 1965, the Kabardino-Balkarian Climbing Competition took place. These climbing events established "golden" (the best of the season) routes of international (sixth) category of difficulty:

- along the northeastern wall of Peak Engels;

- traverse of Peaks Engels and Marx with ascent to Peak Engels via the northern ridge;

- along the eastern wall of Peak Tajikistan (6565 m).

By 1967, several other interesting routes had been completed here:

- a non-classified, but undoubtedly worthy of 5–6 category of difficulty – ascent to Peak Engels via the southeastern ridge;

- ascent to Peak Engels from the Zurgvand pass (5B category of difficulty);

- ascent of 5–6 category of difficulty to Peak Tajikistan from the West Dryj glacier (route of S.M. Savvon's group).

The snow-ice route of 5A category of difficulty to Peak Marx from the east, from the Zurgvand pass, is also noteworthy. And even more routes of various kinds await their climbers.

With modern transportation development, reaching this area might seem not very challenging. However, due to capricious weather in the western spurs of the Pamir and the existence of the so-called Rushan "window" (a narrow gorge under Rushan), flights from Dushanbe to Khorog are often delayed indefinitely. Therefore, getting from Dushanbe to Khorog by ordinary truck is often much faster. After a 400-kilometer journey through numerous spurs to Khorog, the path from Khorog to the village of Lyangar-Kisht (just over 200 km) along the fairly flat and wide Panj River valley, along the border with Afghanistan, does not seem tiring. In Lyangar, we were warmly received by border guards. At the outpost, they allocated a separate hut for our transfer base. The outpost chief helped us contact the local population to hire a pack donkey caravan, as we still had to climb to the planned base camp, considering the cargo, for 5–6 hours.

The base camp of the Donetsk Climbing Competition in the southwestern Pamir was located in the upper part of the Kishty-Dzherob valley, which flows into the Panj valley near the village of Lyangar-Kisht. At the 4100 m mark, approximately 3 km from the end of the glacier tongue, a terminal moraine blocks the Kishty-Dzherob valley, creating a large flat meadow from the alluvial soil. Expeditions from the Spartak Central Council in 1964 and the Kabardino-Balkarian Climbing Competition in 1965 also stopped on this meadow. The conditions for organizing a base camp here are excellent: complete safety, the pack caravan reaches the camp, flat areas for tents, and clean drinking water. In 1967, in addition to the Donetsk Climbing Competition, the Odessa Climbing Competition and the Spartak Climbing Competition of the Moscow City Sports Society were also held here.

The Kishty-Dzherob valley stretches submeridionally for 20 km from northwest to southeast. The western slope of the valley is steep and cliffy throughout most of its length, while the eastern slope is gentle and scree-covered. The valley is blocked by the massif of Peak Engels and Peak 40th Anniversary of Komsomol Ukraine.

Geologically, the bottom of the Kishty-Dzherob valley and its slopes up to 4600–5400 m are composed of ancient Precambrian rocks such as dark gray gneisses with various shades, strong and dense. The upper part of the ridges is composed of:

- magmatic rocks of granitoid composition (western slope of the valley);

- light gray, sometimes white, marbleized metamorphic rocks (eastern slope of the valley and the massif of Peak Engels – Peak 40th Anniversary of Komsomol Ukraine).

Metamorphic rocks of the grain belt are softer and more susceptible to weathering. Throughout the upper part of the Kishty-Dzherob valley, a clear contact line is visible between the lower series of Precambrian gneisses and the upper series of magmatic and metamorphic rocks. On the massif of Peak Engels – Peak 40th Anniversary of Komsomol Ukraine and the Lietuva massif (eastern slope of the valley), well-defined layers of white marble up to 30–40 m thick are also visible in the upper part.

The Kishty-Dzherob glacier is relatively small (about 8 km long) and flat, with a slight icefall only when ascending to the "Nispar pass" in the northeastern part of the glacier. The glacier is closed, with the upper part of the snow cover being 15–20 cm thick. Caldera formation is almost nonexistent, and seracs are rare. The Zurgvand glacier appears similar in its upper part.

The eastern ridge of the Kishty-Dzherob valley has been almost completely traversed. All significant peaks here have been conquered and classified: the Lietuva massif (peaks 5806, 6000, 6080, 6090, and 6141), Peak Tbilisi State University (6141), and the Chermenis and Danilaitis massif. In contrast, on the western ridge, only the peak "5491" near the Bezымяnny pass (5200 m) has been conquered. The peaks between "5491" and Peak Moscow Pravda (6075 m) and further to Peak Pamyati Zhertv Tetnulda (5746 m) not only remain unconquered but also nameless. The eastern slopes of the ridge between Peak Moscow Pravda and Peak Pamyati Zhertv Tetnulda, dropping almost vertically onto the Kishty-Dzherob glacier, look very impressive, and any route laid here undoubtedly deserves the highest category of difficulty.

II. Reconnaissance exits

The base camp of the Donetsk Climbing Competition in the southwestern Pamir was established on June 24, 1967. After its arrangement, starting from June 24, participants of the competition made a series of familiarization, acclimatization, and training exits.

Products and equipment were transported to the assault camp on the eastern (orographically left) lateral moraine of the Kishty-Dzherob glacier, at an altitude of about 4500 m, where a small green meadow had convenient areas for overnight stays. An exploratory-acclimatization exit was made to the upper reaches of the Kishty-Dzherob glacier, where a temporary camp was set up. From here, we ascended to the Bezымяnny pass (5200 m) and the Nispar pass (5350 m) to survey the area and familiarize ourselves with the nearby peaks. During the transportation of products and equipment to the assault camp on the Zurgvand pass (5500 m), where a snow cave was dug for this purpose, we explored the upper reaches of the Zurgvand valley and glacier. All participants of the competition in various groups made training ascents to nameless peaks 5000–5200 m high, rising directly above the base camp in both the eastern and western watershed ridges of the Kishty-Dzherob valley, on non-classified routes of approximately 2–3 category of difficulty.

During these exits, possible ascent routes to the most interesting peaks in the area were explored and studied, thanks in part to the three binoculars available to the expedition. The training council of the Donetsk Climbing Competition selected two very interesting and sufficiently challenging routes for participation in the Ukrainian championship:

- in the class of high-altitude technically complex ascents – to Peak Pamyati Zhertv Tetnulda via the unclimbed eastern ridge;

- in the class of traverses – traverse of the massif Peak 40th Anniversary of Komsomol Ukraine – Peak Engels.

III. Brief description of ascent conditions

The southwestern Pamir is characterized by very stable good weather. This was confirmed during our stay in the Kishty-Dzherob valley. Over 43 days (from June 22 to August 3), the base camp experienced cloudy weather only 2–3 times, typically for a very short period (2–3 hours). During this time:

- the cloud cover was light;

- no precipitation fell.

"Up high," groups sometimes encountered a cloud band, which significantly reduced visibility and brought light snowfall. Occasionally, strong winds were observed during ascents. Overall, weather conditions were fully satisfactory:

- the vast majority of ascents were made in clear weather;

- bad weather did not disrupt any ascents.

Similar reports were read in the reports of all previous expeditions to this area, so we did not expect any surprises from the weather – and were not disappointed.

According to local residents, later fully confirmed by our observations, the winter of 1966–1967 was unusually snowy. Therefore, during our ascent to Peak Pamyati Zhertv Tetnulda (5746 m), we were prepared to encounter wet rocks and snow in "unusual" places. During a training ascent, we found that the ridge between peaks "5746" and "5041" (our planned descent route) was covered in deep, loose snow. Although it was clear that with the typical lack of precipitation in the area, this ridge would largely be scree-covered.

Given the abundance of snow, we expected the summit tower to be covered with a significant layer of snow and were prepared not to deal with ice. Consequently, we did not bring crampons, but it turned out that they would have been useful on the last few meters. Our mistake was likely due to:

- the slope being steeper than we anticipated;

- the sun warming the slope during the day, preventing snow from sticking, even with abundant snowfall.

We did not notice any alarming features in the structure of the rocks that made up the majority of the route during our study, although we specifically examined the scree at the base of the eastern ridge of peak "5746". The rocks did not present any unexpected challenges during the ascent. Their relief was complex in many places, but we were prepared for this.

The participants' health, according to the expedition doctor, did not raise any concerns. Everyone was well-trained. After two weeks in the area, the group was fully acclimatized. The mood among participants during the ascent was good, with no moral depressions observed. Everyone worked equally to overcome the route.

All the equipment we brought was thoroughly checked and tested at home, and at the base camp, it was gradually prepared for use. For the ascent, we only took titanium rock hooks. Such hooks have recently gained popularity and received excellent reviews from all groups that have used them. We can also attest that titanium hooks:

- are stronger;

- more economical and versatile than ordinary steel hooks;

- last longer;

- are twice as light.

Titanium carabiners are equally reliable. The rope carabiners we used are also not a rarity. We used them only on sections where a long rope had many driven hooks. In such cases, after 3–4 metal carabiners, we hung a rope carabiner. All the equipment used withstood the ascent well.

IV. Organizational and tactical ascent plan

From reference literature, "List of Alpine Ascents," we knew that Peak Pamyati Zhertv Tetnulda (5746 m) was conquered and named in 1954 by a group of participants from the Georgian Alpine Club led by M. Gvarliani. However, this was the extent of our reliable information; the rest was based on verbal accounts. According to stories, we knew that:

- the Georgian climbers ascended peak "5746" from the west, from the Zurgvand valley;

- they rated the route as 4A category of difficulty.

However, this route was not listed in the "Classification Table of Peaks of the USSR" among approved routes. We did not have even an approximate description of this ascent to repeat it and scout our planned route from above. When we ascended to peak "5041" during a training climb, we saw that the ridge leading to peak "5746," as we had assumed, was a very simple snow ridge of 1–2 category of difficulty. However, the snow was so loose that we sank up to our knees, and sometimes deeper. The ascent to "5746" was very slow and tiring. To reach the summit, we would have had to set up an unplanned cold bivouac.

Therefore, we abandoned attempts to view the eastern ridge of Peak Pamyati Zhertv Tetnulda directly from the summit. Moreover, there was no particular need for this, as we had studied the route in detail using binoculars both from the base camp and "up close" from the western slopes of the eastern watershed ridge of the Kishty-Dzherob valley.

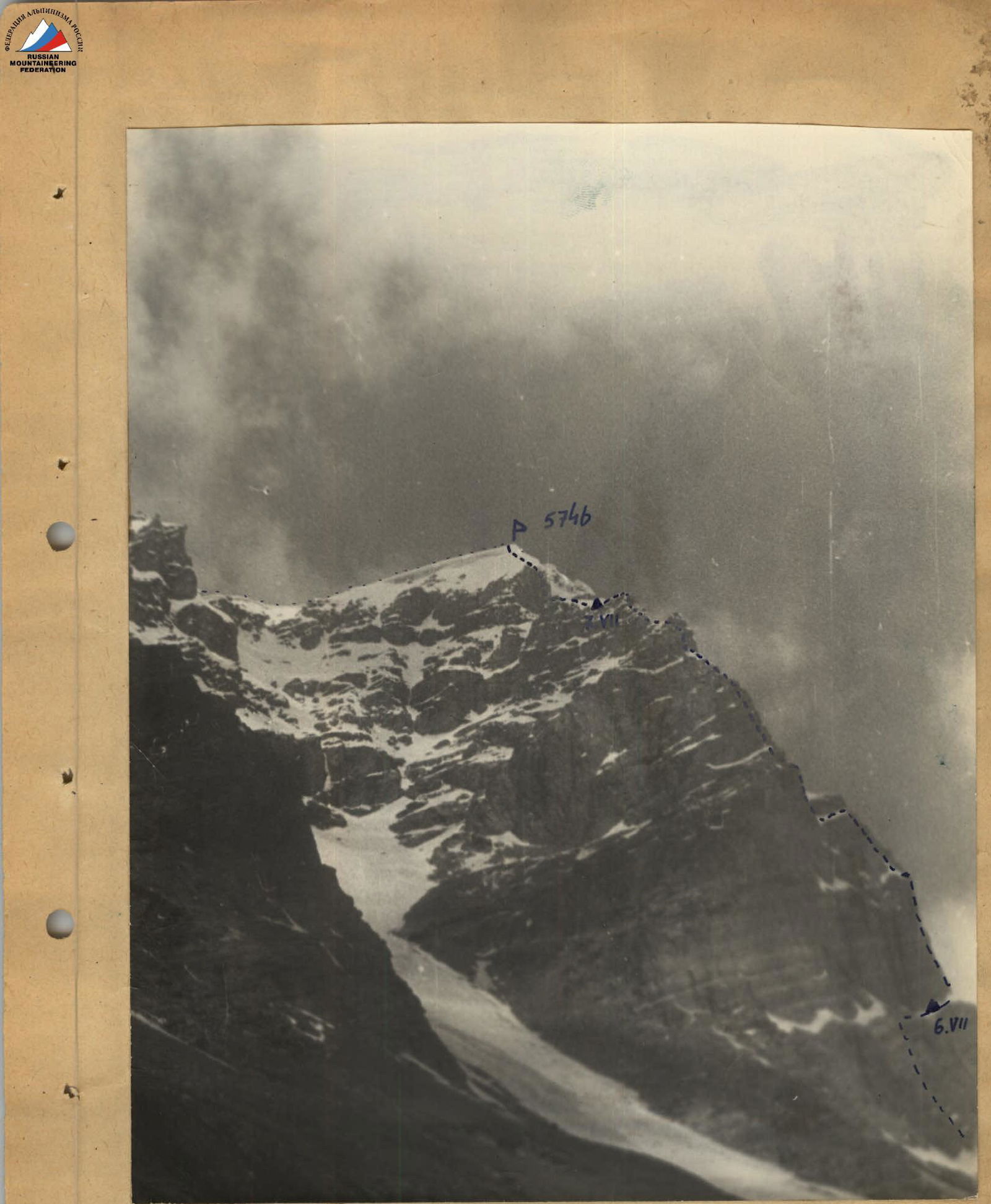

General view of the eastern ridge of Peak Pamyati Zhertv Tetnulda (5746 m) from the area of the Base Camp at 4100 m. — path of ascent … path of descent

We even had a sufficient understanding of the mechanical properties of the rock formations on the route by examining the scree at the base of the ridge.

The route was largely rocky, with several sections presenting very difficult passage. However, our available equipment (see the list of group equipment at the end) allowed us not to retreat even before sheer monolithic walls. Such walls, if present, were of insignificant length – no more than a rope in each case. As the ascent later showed, we correctly assessed the rocky relief, and our equipment set was fully satisfactory for the route. We only erred in assessing the snow-ice slope of the summit tower: we expected it to be more gradual and with a sufficiently deep snow cover, but it turned out that the last two ropes of the ascent to the pre-summit ridge represented a steep ice ascent, only lightly (1–2 cm) covered with snow. However, even if we had known the true state of affairs, we would not have taken crampons because they would have been a useless burden for a significant part of the ascent.

The non-standard equipment we used (titanium hooks and carabiners, rope carabiners, duralumin piton hooks, jammers) was not new to us. We had used it multiple times on ascents of various complexities in the Caucasus. Additionally, before the start of each season, we conduct mass tests of such equipment on our home rock climbing site – in the Zuev quarries. Almost all of these types of equipment are widely used by many alpine sections. Rope carabiners, when used correctly, also fully ensure the safety of the ascent and provide significant weight savings.

All participants of the Donetsk Climbing Competition engaged in general physical training year-round in their sports clubs or in the regional alpine section (for Donetsk residents), and before departing for the mountains, everyone passed control standards in general physical preparation. Additionally, during the spring period, every Sunday and on pre-holiday days, we gathered at the rock climbing site to improve our rock climbing technique and practice various options for overcoming rock walls using different types of equipment.

The height of Peak Pamyati Zhertv Tetnulda is not very significant by Pamir standards, but the alpine competition plan still required all participants of the assault group to gain sufficient acclimatization by the time of the ascent. Before heading out on the ascent, everyone had been to altitudes of around 5500 m.

We decided to monitor the assault group directly from the base camp, as the entire route was visible through binoculars and was in close proximity. For this purpose, Masters of Sports of the USSR Sivtsov B.G. and Laukhin Z.V., and 1st category athletes Alekseenko A.A. and Radashkevich A.P. remained at the base camp. This group, led by Sivtsov, was to intervene on the route if necessary as a forward rescue team.

According to the preliminary tactical plan, the assault group was to leave the base camp at dawn to begin processing the most challenging section of the path – the first rock wall – on the same day, especially since it was the beginning of the route, and a convenient (as it seemed from below) wide scree-covered shelf was nearby to set up a bivouac. If processing the wall required a lot of time, we were to spend the night on top of the wall the next day.

The further tactical plan provided:

- only the general character of the movement;

- methods for overcoming the most challenging sections.

If necessary, the group was to be prepared for sitting overnight stays. The duration of the stay on the route was at the group's discretion. The return route was planned through peak "5041".

The assault group largely adhered to this tactical plan. However, thanks to the group's good pace and perseverance, sitting overnight stays were not necessary. The group took provisions for 4.5 days. Nutrition on the route was organized normally.

V. Composition of the assault group

We decided to make the first ascent of the eastern ridge of Peak Pamyati Zhertv Tetnulda with the most mobile group – a foursome. Oleg Polyakovsky was appointed as the leader of the ascent.

The group included:

- Polyakovsky Oleg Ivanovich – 1936 birth year, Polish, CPSU member, Candidate for Master of Sports, alpine experience – 13 years, senior geologist at the Artemovsk Complex Geological Exploration Expedition of the "Artemgeology" trust, Artemovsk, Donetsk region, st. Artema, 40, apt. 47.

- Zhelobotkin Petr Ivanovich – 1941 birth year, Russian, Komsomol member, Candidate for Master of Sports, alpine experience – 9 years, mining engineer. Donetsk, st. Universitetskaya, 168, apt. 33.

- Zolotayev Leonid Pavlovich – 1934 birth year, Russian, CPSU member, Candidate for Master of Sports, alpine experience – 12 years, metallurgical engineer. Kommunarsk, Lugansk region, st. Lenina, 74.

- Rusanov Viktor Nikolaevich – 1938 birth year, Russian, non-partisan, Master of Sports, alpine experience – 14 years, mining technician. Donetsk-58, st. Revolyutsionerov, 91.

VI. Description and order of passage of the route

On July 6 at 6:00, the group in the above composition left the base camp, ascending up the Kishty-Dzherob river along its right bank. The eastern ridge of Peak Pamyati Zhertv Tetnulda drops into the Kishty-Dzherob valley at the point where the glacier ends. Upon reaching this location, we turned left and began ascending a wide couloir to the left of "our" ridge. The reason was that 300–350 m up the ridge, a wide inclined scree-covered shelf stood out. Ascending to it directly via the steep walls of the ridge made no sense, as a simple and logical path led there through the couloir bounding the eastern ridge of Peak Pamyati Zhertv Tetnulda on the left.

Characteristics of the couloir:

- Filled with snow and cut by avalanche grooves along the center.

- Steepness in the lower part is about 30–35°.

- The couloir is surrounded amphitheatrically at the top by the main watershed western ridge of the Kishty-Dzherob valley, which overhangs here with numerous cornices.

Due to the high danger of advancing along the central part of the couloir, we moved along the least dangerous left side of the couloir (R1). The width of the couloir in the lower part is 60–70 m. After reaching the level of the scree-covered shelf, we continued moving with insurance and all precautions:

- quickly crossed the couloir to the right, one by one;

- reached the shelf.

Our altimeter showed an altitude of 4550 m.

The shelf was very wide (up to 100 m), entirely covered with stones of various sizes, and inclined to the southeast at an angle of about 10°. We ascended along it (R2) to the sharp rise of the eastern ridge. At this point, the eastern ridge drops to the north with a completely sheer monolithic wall. To the east, after the end of the shelf, a 200-meter ridge of moderate steepness (about 75°) descends into the Kishty-Dzherob valley, with minimal holds. To the west, the ridge rises with an 80° wall. It is from this wall that the ascent directly along the eastern ridge of Peak Pamyati Zhertv Tetnulda begins.

We reached the shelf at 10:00. We took a break and had a snack. Zolotayev and Zhelobotkin worked on organizing the bivouac and preparing food, while the Polyakovsky-Rusanov team began processing the route at 11:00.

The beginning of the route was most simply accessed 45 m to the left of the ridge edge. The wall here is stepped, and the rock relief is quite straightforward to navigate. However, at a height of 40–45 m, the wall's steepness increases sharply to negative, and a rock overhang hinders further viewing of the route. Therefore, we decided to ascend directly at the ridge edge. Almost along the entire length of the first rope (R3), a crack runs 0.5 m from the right edge of the rock. For safety, we did not use it for insurance, especially since we could always find another crack for a hook, but we often used it for climbing, as it accommodates a full hand. We passed the first rope (40 m) in 2 hours 30 minutes, using 11 hooks, including one piton. Polyakovsky led first, then we switched, and Rusanov led the second rope. The wall here remained slightly gentler (75°), but more complex for passage, as the crack ended, and there were fewer holds for climbing and good cracks for hooks. It was complicated by a system of short (4–5 m) internal corners. Although they were not directly above each other but 2–3 m to the right and left, so at one point, we used a "pesenka" (a small ladder or step) as an additional support to transition from one internal corner to another. We took 3 hours to pass the second rope (R4), using 12 hooks, including 1 piton for the ladder.

At the end of the second rope, there is a fairly convenient insurance platform, 40 cm wide and 1.5 m long. However, we did not continue further, as the remaining 35 m of the wall was the most complex part, and we wouldn't have been able to complete it before dark.

The Polyakovsky-Rusanov team descended to the bivouac, which by then was arranged with possible comfort. At dusk, observers from the base camp signaled that they had seen us. We responded that everything was fine.

On July 7, we woke up at 7:00, and at 8:20, the Polyakovsky-Rusanov team began the ascent. The Zolotayev-Zhelobotkin team dismantled the bivouac, packed all the backpacks, left the first control cairn at the bivouac site, and started on the route at 9:00.

While the second team was pulling up the backpacks, Polyakovsky began overcoming the last third of the wall (R5). The ascent was directly upwards, 1.5–2 m from the right edge of the rocks. There were minimal holds, and cracks were only suitable for petal hooks. After 20 m of difficult climbing, we could only proceed using ladders. We passed 8–10 m on ladders and saw a zigzag transition to the left into an internal corner. For the traverse to the left, we needed to drive in 2 piton hooks.

Further:

- 7 m of not very difficult climbing along the internal corner;

- a good platform on the ridge, large enough for a tent.

Here, we all gathered, pulled up the backpacks.

Rusanov led next. 20 m along the destroyed ridge of medium difficulty (R6). Another 20 m along very steep deep snow to bypass a rock outcrop on the right (R7), and we were back on the ridge. The rope proceeded along the ridge, which consisted of large-block rocks (R8), and before us was a two-tiered sheer wall.

Assessing the situation, we decided to bypass the first tier of the wall on the left towards a system of wet, inclined ledges. One rope length in this direction (R9).

- Initially, a traverse with a slight gain in height along simple scree.

- Then the scree becomes increasingly difficult with each step.

- Finally, the last 2–2.5 m involve traversing a sheer monolithic face of an internal corner and transitioning to the ledges on the left wall.

For the transition, we drove in two piton hooks and hung two ladders.

The ledges were covered with stones and gravel, and water flowed over them. So, while the advance along them was not technically complex, it had to be done very carefully (R10).

From the ledges, we exited to the right onto the ridge – onto the first tier of the wall. From here, we could see a logical path to bypass the second tier of the wall on the right. One rope length along easy, destroyed rocks (R11), and we entered a steep and narrow couloir descending from the ridge.

- We ascended 30 m along the couloir;

- the couloir slope was along the right side;

- movement was along the edge of snow and rocks;

- we drove hooks for insurance into the rocks;

- further, the couloir became icy.

We exited onto the rocks on the right side of the couloir. From here, one rope length of very difficult but enjoyable climbing along steep (75°) rocks with monolithic holds (R13) led us to the ridge.

The ridge was heavily destroyed, and it was better to move to the left of it along scree-covered ledges. Two rope lengths of straightforward progress (R14) – and the rocks ended.

We ascended along snow to the ridge (R15). We rested, had lunch, and left the second control cairn on a large flat stone.

The second team led next. Two rope lengths along a not very steep (20°) but narrow snow-covered ridge (R16), and again we faced a wall, with no visible bypass either to the left or right. Zhelobotkin began the ascent along the left part of the wall, where it was less steep (60°). One and a half rope lengths of climbing along large-block rocks of above-average difficulty (R17), and the wall's steepness increased sharply to 80°. Zhelobotkin passed one rope length of very difficult climbing (R18), driving in piton hooks in three places and hanging ladders, and reached a small inclined platform before an internal corner. By time, it was already 19:00, and it was time to stop for the night, but the platform was so small and inclined that even standing there was difficult for the three of us, and we still had to pull up the backpacks.

The internal corner looked as follows: the right side, up to 2 m wide, rose not very steeply (50°) but was completely smooth and dropped sheer to the right. The left side rose vertically for 10 m, where a kind of balcony was visible. There were no opportunities here either, but in the middle, there was a chimney that could accommodate half a body.

Zhelobotkin, wriggling, climbed the chimney (R19) to the balcony and secured the rope there. We pulled up the backpacks and climbed up one by one using the secured rope on jumar.

Further:

- 2 rope lengths of climbing along large-block rocks of medium difficulty (R20) bypassing the remaining part of the wall to the left;

- and at 20:50, we exited onto the ridge before a small snow field.

On the snow field, near a rock outcrop, we trampled a convenient platform and set up a bivouac, securing ourselves through hooks driven into the rock outcrop. We signaled to the base camp and received a response signal.

On July 8, we woke up reluctantly at 7:00 and saw with little regret that there was bad weather behind the tent. We decided to rest after the very intense previous day. However, by 9:00, the clouds dispersed, the snowfall stopped, and we decided to proceed. Zolotayev and Zhelobotkin left the bivouac at 10:00, and the Rusanov-Polyakovsky team at 10:30.

From the overnight stay, one and a half rope lengths of ascent along a narrow snow-covered ridge with rare rock outcrops (R21) led us to another wall.

We ascended first one rope length upwards in a spiral along not very difficult large-block rocks (R22), and then 20 m in the same direction along rocks of the same complexity but covered with rime ice (R23). This significantly complicated our progress. Zolotayev had to clear every hold and every crack for a hook from ice.

This wall ended with a 5-meter completely smooth overhang, intersected 1 m from the top by a wide horizontal crack. The crack was about 7 m long, and by crawling along it, pulling our backpacks behind us, we could reach the left edge of the wall. We chose this option (R24) to exit to the ridge.

The wide ridge here, for two rope lengths, consisted of gentle (45°), stepped rocks (R25). Progress was significantly hindered by the fact that they were covered with snow. After us, a clear track remained – a narrow strip of rocks cleared of snow, 3–4 m to the left and below the ridge itself.

The next rock ascent, with an average steepness of about 65°, was a continuation of the rocks of the same character and structure as the ridge before, but because the rocks became steeper, the snow did not stick here. The length of this section (R26) was about three rope lengths, with a technical difficulty above average.

The last rock belt ended with a 40-meter slab section (R27). The steepness here was about 55°. There were not many holds, but the slabs were broken into separate blocks by a network of thin cracks. By driving petal hooks into the cracks, we created additional points of support. Rusanov passed this section without a backpack, while Zhelobotkin, following, carried his backpack and pulled up Rusanov's backpack on a схватывающий (a type of climbing knot or device), as pulling the backpack up the usual way on such steep rocks was very difficult.

Above, there was a small snow mulde located between the eastern ridge of Peak Pamyati Zhertv Tetnulda and the main watershed ridge bounding the Kishty-Dzherob valley from the west. On the mulde, we rested and had lunch. We could have crossed the mulde to the left and immediately ascended to the main watershed ridge, and then along it to the summit. However, this would have been very dangerous, as the watershed ridge was crowned with huge cornices along its entire length, and we would have had to ascend directly under such a cornice with insurance only through an ice axe. But in the place where "our" ridge joined the main watershed ridge, just below the summit of Peak Pamyati Zhertv Tetnulda, there was no cornice, so we had no choice but to continue along the eastern ridge. After the slabs, for 3–3.5 rope lengths, we traversed a snow slope with a steepness of 30–35° and already thawing deep snow at that time (R28). Further, there was a sharp bend in the slope, and before us lay an ice wall, lightly (1–2 cm) covered with snow, with a steepness of up to 60–65° and a length of two rope lengths (R29). We had to cut steps and drive in ice hooks more frequently since we did not have crampons. Finally, we reached the gentle (20–25°) watershed ridge and, after three rope lengths of ascent along it (R30), stood on the summit of Peak Pamyati Zhertv Tetnulda. The time was 15:00, and our altimeter showed a height of 5750 m.

Prolonged searches for a summit cairn yielded no results. We built our own cairn and left a note about the ascent and the route taken. We descended along the watershed ridge to the south, towards peak "5041". The ridge was simple, flat, without sharp ascents, and even the deep snow did not significantly slow our descent. After passing peak "5041", we continued descending along scree and grassy slopes. At 21:00 on July 8, we were back at the base camp.

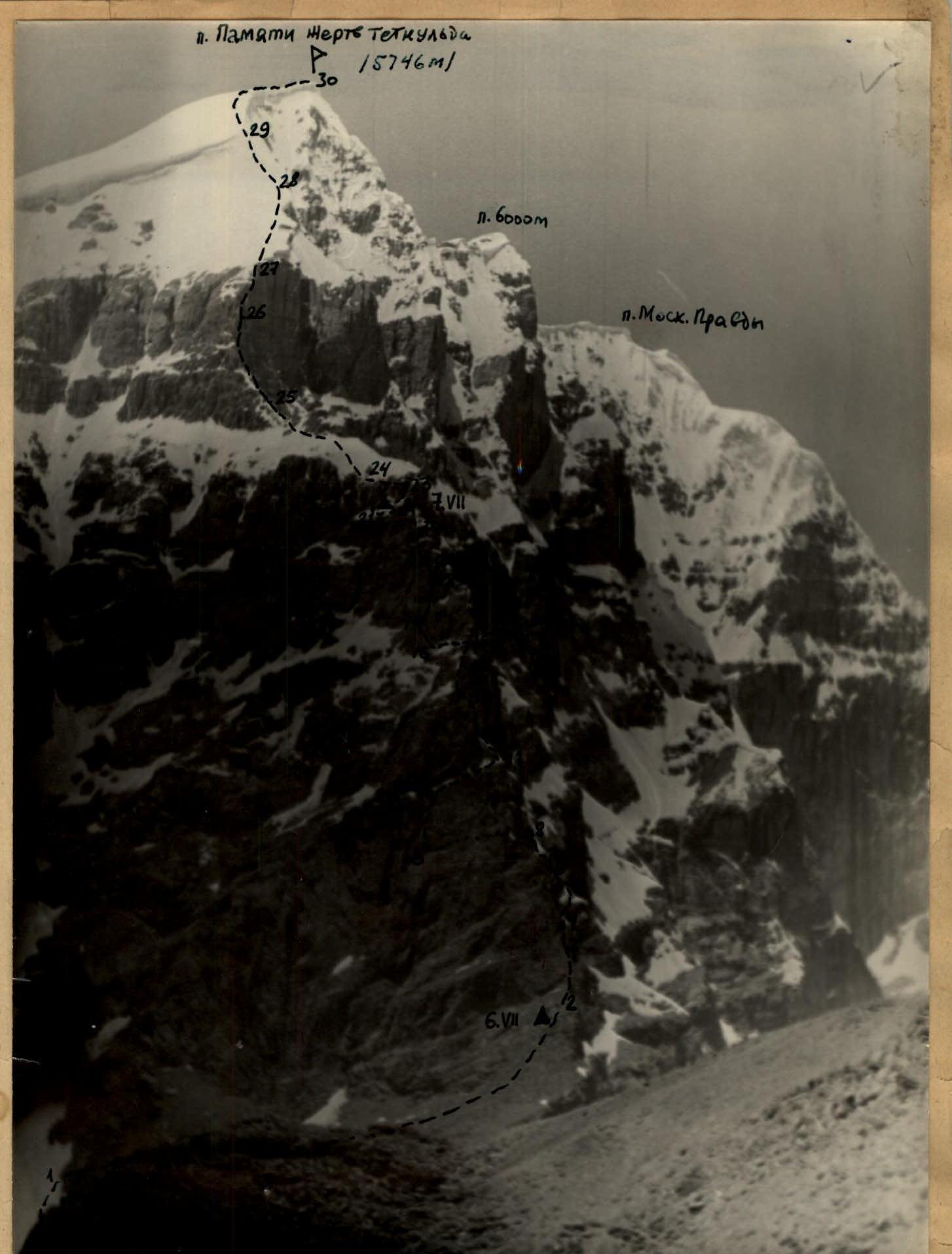

The ascent route to Peak Pamyati Zhertv Tetnulda (5746 m) along the Eastern ridge. Photograph from the slopes of the Lietuva ridge. The route length is about 2000 m. The height difference from R2 to R30 is about 1200 m.

VII. Overall assessment of the actions of the assault team

All participants of the assault group were very well-prepared for the ascent. The group studied the route in detail and considered all details when selecting equipment and supplies.

Each participant:

- performed the functions assigned to them during the development of the tactical ascent plan;

- led the way, laying the route on a specific section;

- demonstrated themselves to be sufficiently competent climbers, capable of coping with any difficulties on the route.

The entire group acted cohesively and organized during the assault, maintaining a very high pace of movement while strictly adhering to all rules of safety techniques during mountaineering.

VIII. Additional data on the route characteristics

The height gain during the first ascent of the eastern ridge of Peak Pamyati Zhertv Tetnulda by the Donetsk Climbing Competition group in the southwestern Pamir from the wide scree-covered shelf to the summit was approximately 1200 m. Of this:

- About 1000 m (4550–5550 m) was traversed along rocks with very complex relief.

- About 200 m of height gain is attributed to the snowy summit tower with a difficult ice wall in the middle.

Thus, the route can be considered combined, requiring sufficient proficiency in ice climbing techniques.

The state of the route during typical low-snow winters in this area will not differ significantly from the above description. As snow melts from the rocks of the ridge in places where it remained during our ascent, passage will become easier. However, firstly, these places are not key, and secondly, with little snow, ice will be exposed in the steep (60°) narrow couloir on the two-tiered wall (R12 – 30 m), and the pre-summit ice wall will lengthen by 20–30 m, emerging from under the snow. It is not possible to bypass this wall without risking being caught under a cornice collapse. Thus, the overall complexity of the route remains constant during the summer with stable weather in these areas.

A very positive aspect of such a complex route is that there is a very straightforward descent from the summit and that it is located in close proximity to the base camp.

Most members of the assault group (except P.I. Zhelobotkin) have completed 9–10 ascents of 5 category of difficulty in the Caucasus and Pamir, including 5–6 routes of 5B–6B category of difficulty. The route along the eastern ridge of Peak Pamyati Zhertv Tetnulda is one of the most challenging in the "arsenal" of the assault participants.

Therefore, the group participants and the leadership of the Donetsk Climbing Competition propose classifying this route as 5B category of difficulty.

Head of the Donetsk Climbing Competition in the southwestern Pamir (B