Passport

I. Altitude-Technical Class

-

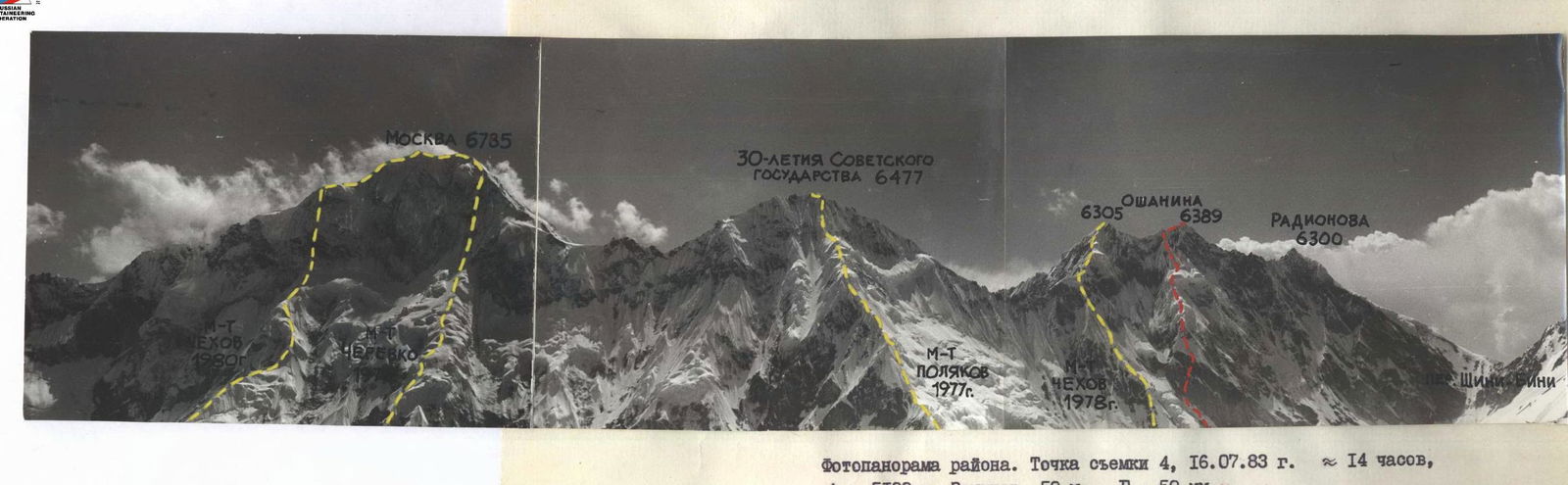

Central Pamir, Peter the First Ridge

-

Peak Oshanina (6389 m) via the North face

-

Expected — 6th cat. diff., first ascent

-

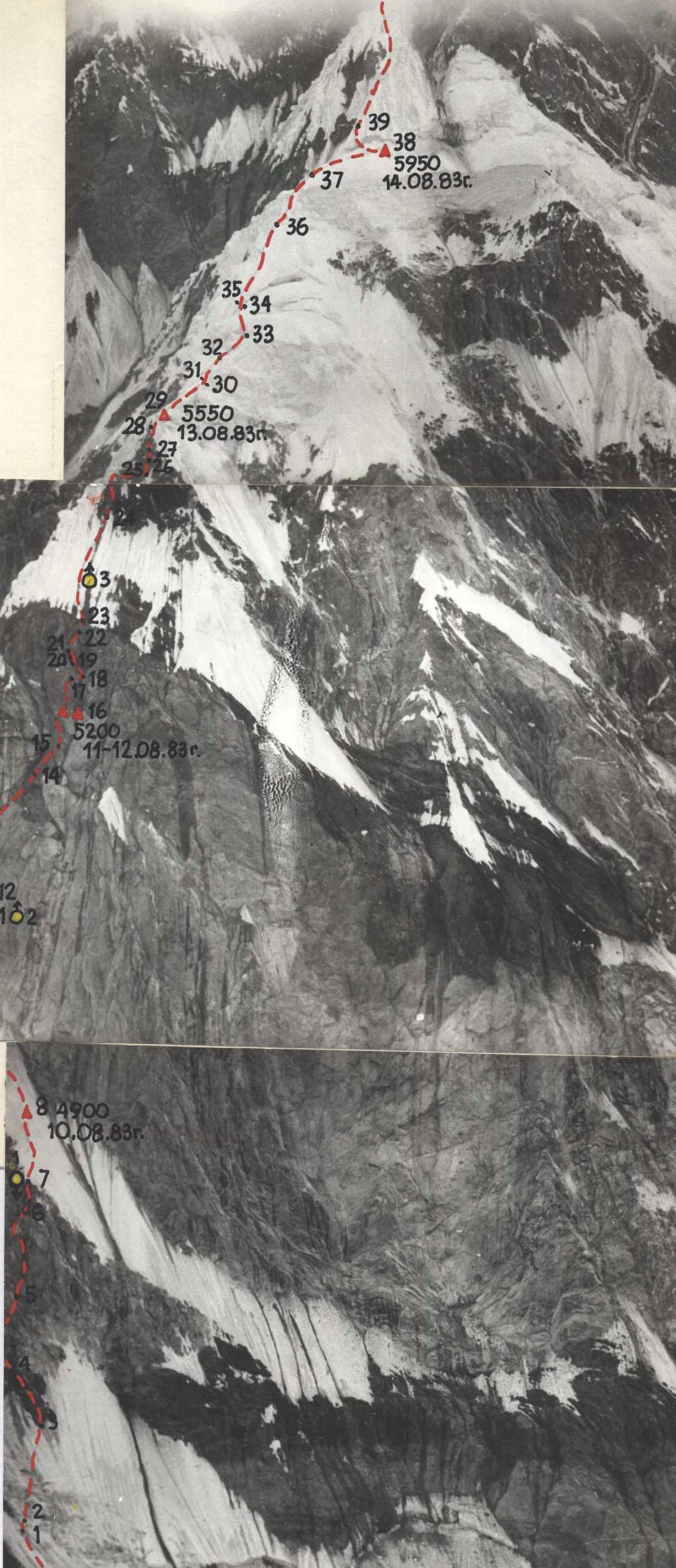

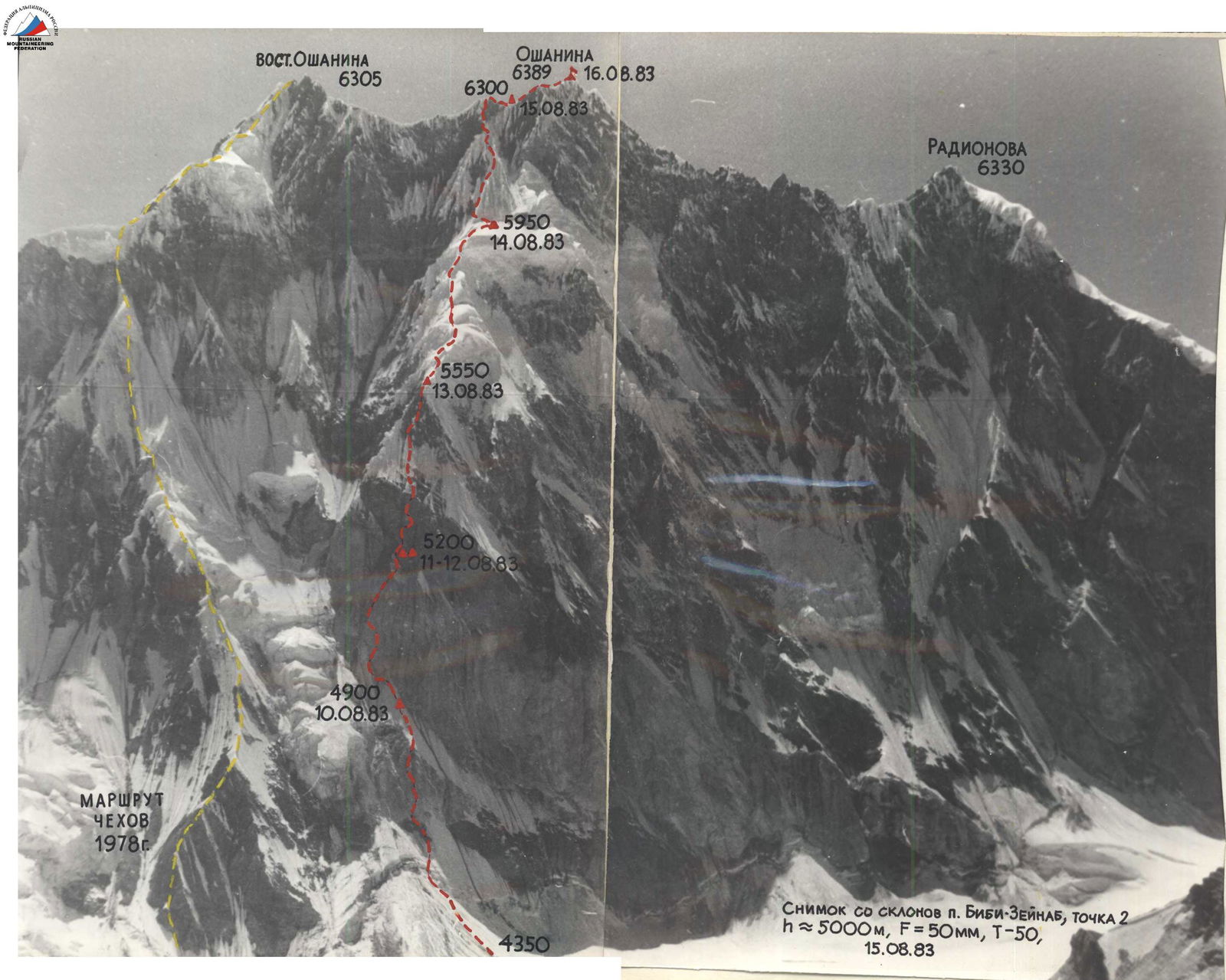

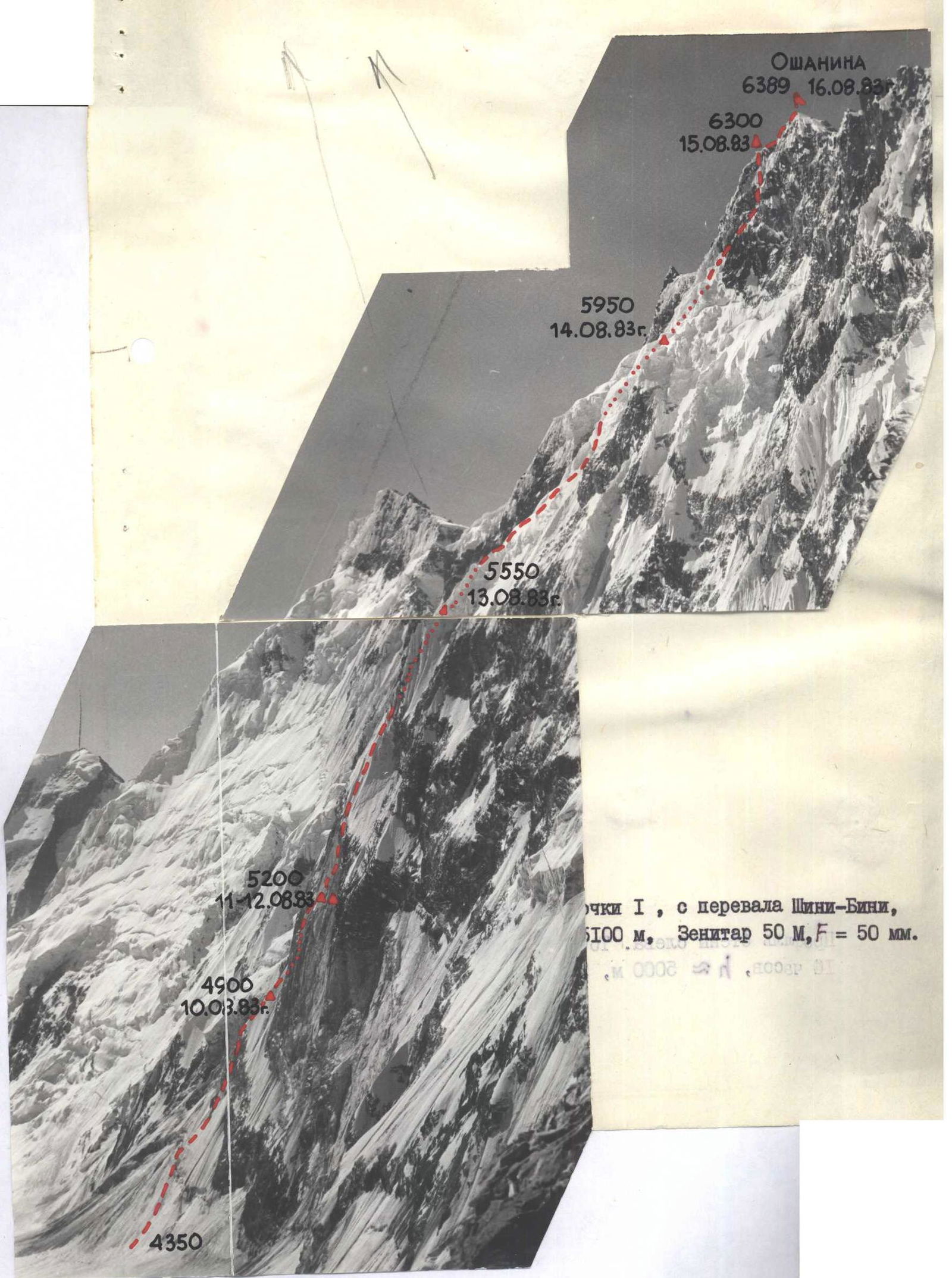

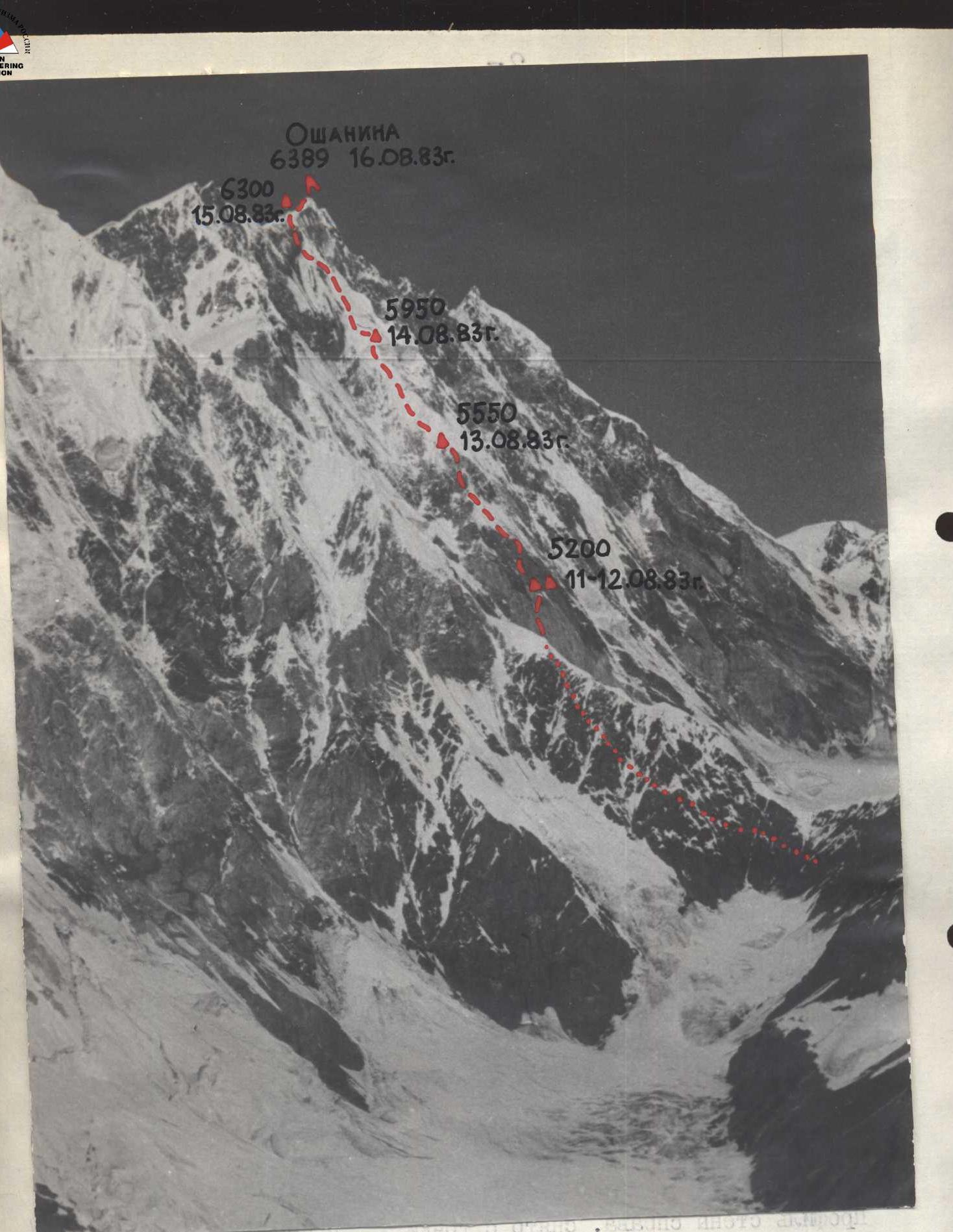

Elevation gain: 2040 m, length ≈ 3000 m, length of sections with 5–6 cat. diff. — 1350 m, average steepness of the main part of the route 60° (4500–6300 m), including 6 cat. diff. 76° and 110° (≈ 5000 m), 80° (5200–5250 m), 80° (6230–6300 m) — total 190 m.

-

Pitons driven: rock screw anchors ice 113/IX 0/0 14/II 66/0

-

Climbing hours to the summit 59; days — 7

-

Bivouacs: 1, 4, 5 — lying, carved into the snow-ice slope; 2–3 — sitting, on a rock shelf; 6 — lying, in a hollow under the summit; 7 — lying, carved into the snow-ice slope, on descent.

-

Captain: Boyko Valery Viktorovich — MS

Deputy Captain: Efimov Viktor Borisovich — MS

Participants:

- Kolobaev Sergey Petrovich — CMS

- Kalagin Yuri Grigorievich — CMS

- Lapin Vladimir Alexandrovich — CMS

- Ryabov Nikolai Alexandrovich — CMS

-

Coaches: Zhurzhdin Vladimir Iosifovich — MS

Vinokurov Anatoly Filippovich — MS

-

Departure to the route: August 10, 1983

Processing — August 8, 1983 Summit — August 16, 1983 Return — August 17, 1983

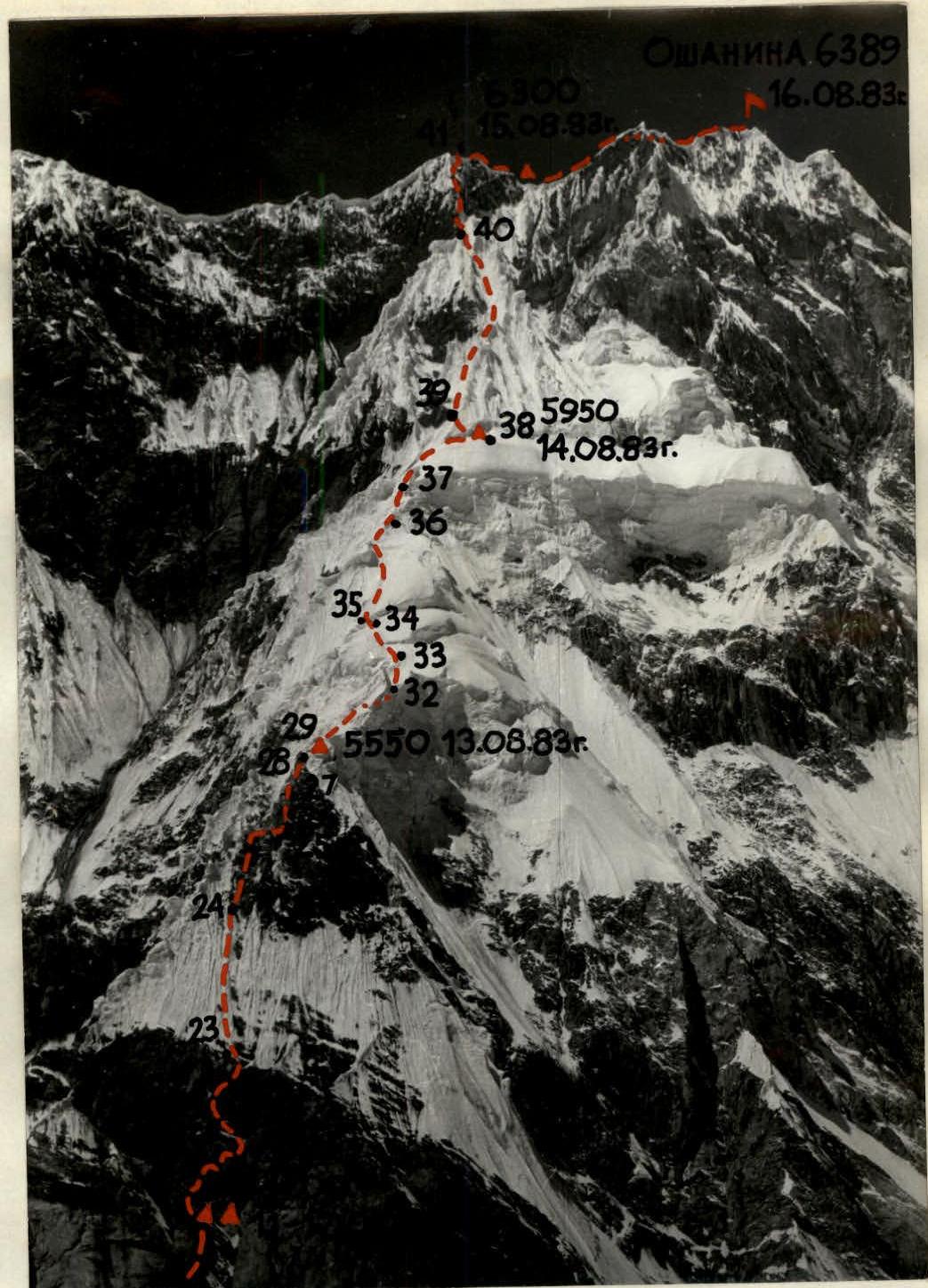

Photo from the slopes of Peak Bibi-Zeynab, point 2, h ≈ 5000 m, F = 50 mm, T = 50, August 15, 1983.

Team's Tactical Actions

The core of our team was formed in 1980 when three of its members, Boyko, Efimov, and Ryabov, participated in the USSR Championship for the first time. Since then, the team, with varying compositions, has climbed various walls, including:

- Ushba

- Chatyn

- Mizhirgi

- Zindon

- Chapdara

- Guamysh

The tactics employed during our ascent of Peak Oshanina were no different from those used in these previous climbs.

Throughout the route, we moved on a double rope, utilizing the so-called "caterpillar" scheme. This tactic allows everyone except the lead climber to ascend on fixed ropes with top-rope protection and has been a long-standing practice for our team. We ascended on two "Jumars": the upper one attached to the harness, and the lower one with a ladder. This method of ascending on fixed ropes has also been used by our team for a long time, enabling us to climb without pulling up backpacks (wearing them on our backs), and if needed, ascending with two backpacks (the second backpack attached to the belt).

The second climber in our team also ascended with a lightened backpack and carried a hammer (ice axe), adjusting the fixed ropes as needed to make the ascent more comfortable for the rest of the team. We used fixed ropes throughout most of the route, except for sections:

- 1

- 3

- 30

- 32

- 34

- 38

- 39

The lead climber typically worked alone for the entire day, and the order of ascent for the rest of the team was predetermined, with the team members generally maintaining their order throughout the day.

We rotated the roles of first, second, and last climbers daily, allowing everyone to work in different capacities and avoid excessive fatigue. This rotation is crucial for the complexity of routes climbed by top teams today and undoubtedly enhances the reliability and safety of the ascent.

Different team members led on various sections:

- Boyko (sections R7–R11, R19–R29)

- Ryabov (R1–R6, R12–R18)

- Lapin (R30–R38)

- Efimov (R39–R41)

We made extensive use of route processing. At the beginning of the route, we processed 8 ropes (sections R1–R6), which allowed us to ascend the lower part of the wall more quickly and reduce the number of uncomfortable bivouacs on the wall. We typically started our bivouacs early to process several ropes simultaneously while preparing the campsite (sections R9–R11, R17–R22), conserving energy and time.

The team largely adhered to the tactical plan developed during the ascent planning. Some deviations were due to bad weather:

- We waited out bad weather at the bottom after processing the route for 1 day;

- We waited for 1 day at the second bivouac.

The tactical plan had reserved one day for bad weather. Therefore, the team returned to the base camp only on August 17.

We employed new types of equipment, including ice screws (Ice Fi Fi) on both ice and snow, and self-drilling ice anchors during the descent. Both innovations performed very well. The use of Ice Fi Fi, in particular, helped us navigate the "krovavyi mal'chiki" (bloody boys) when exiting onto the pre-summit ridge, which is a conglomerate of ice, firn, and loose snow.

We maintained radio contact with observers four times a day (8:00, 12:00, 16:00, and 20:00) using the "Vitalka" radio station. Visual observation allowed the observers to guide our route choice.

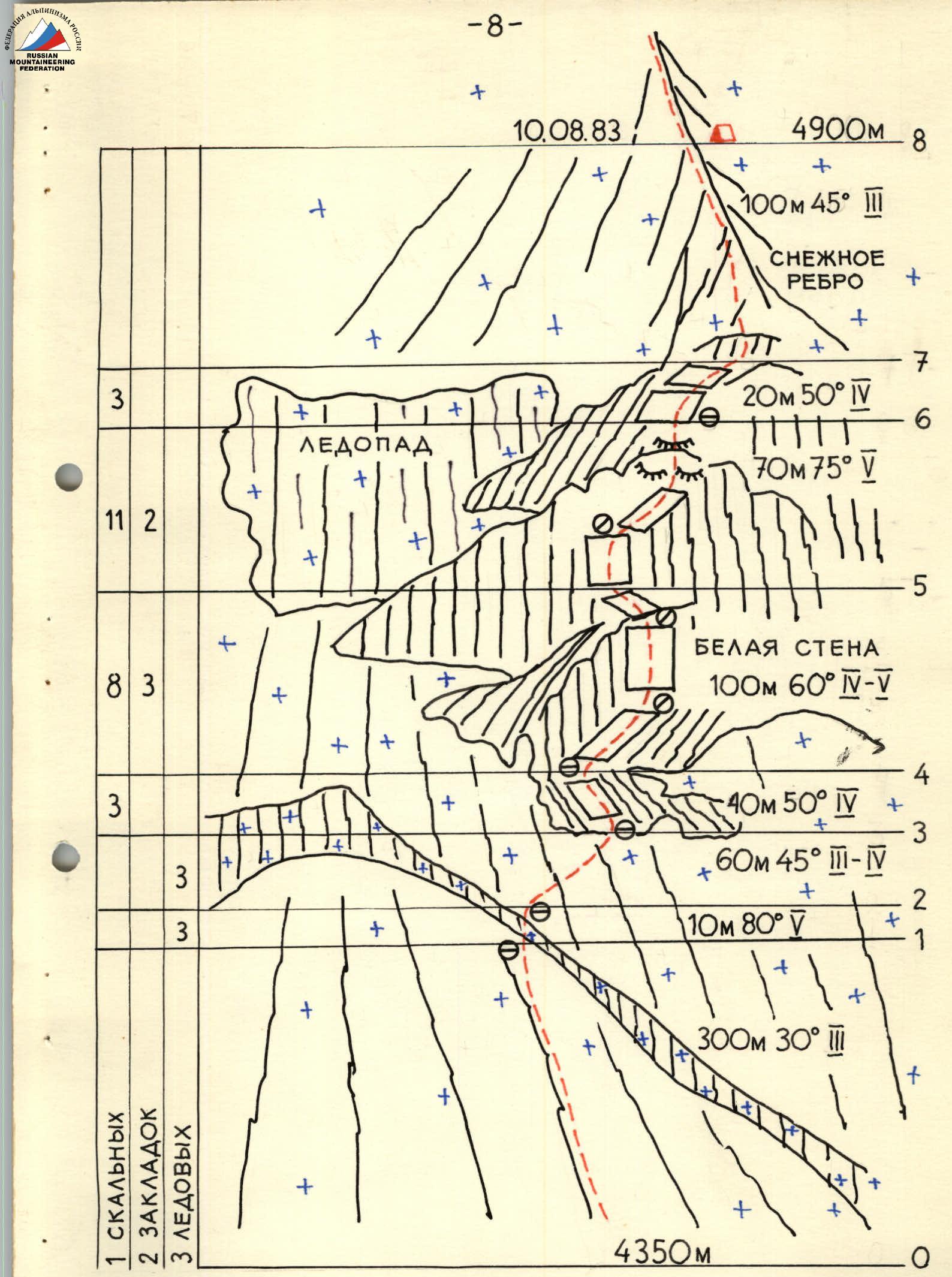

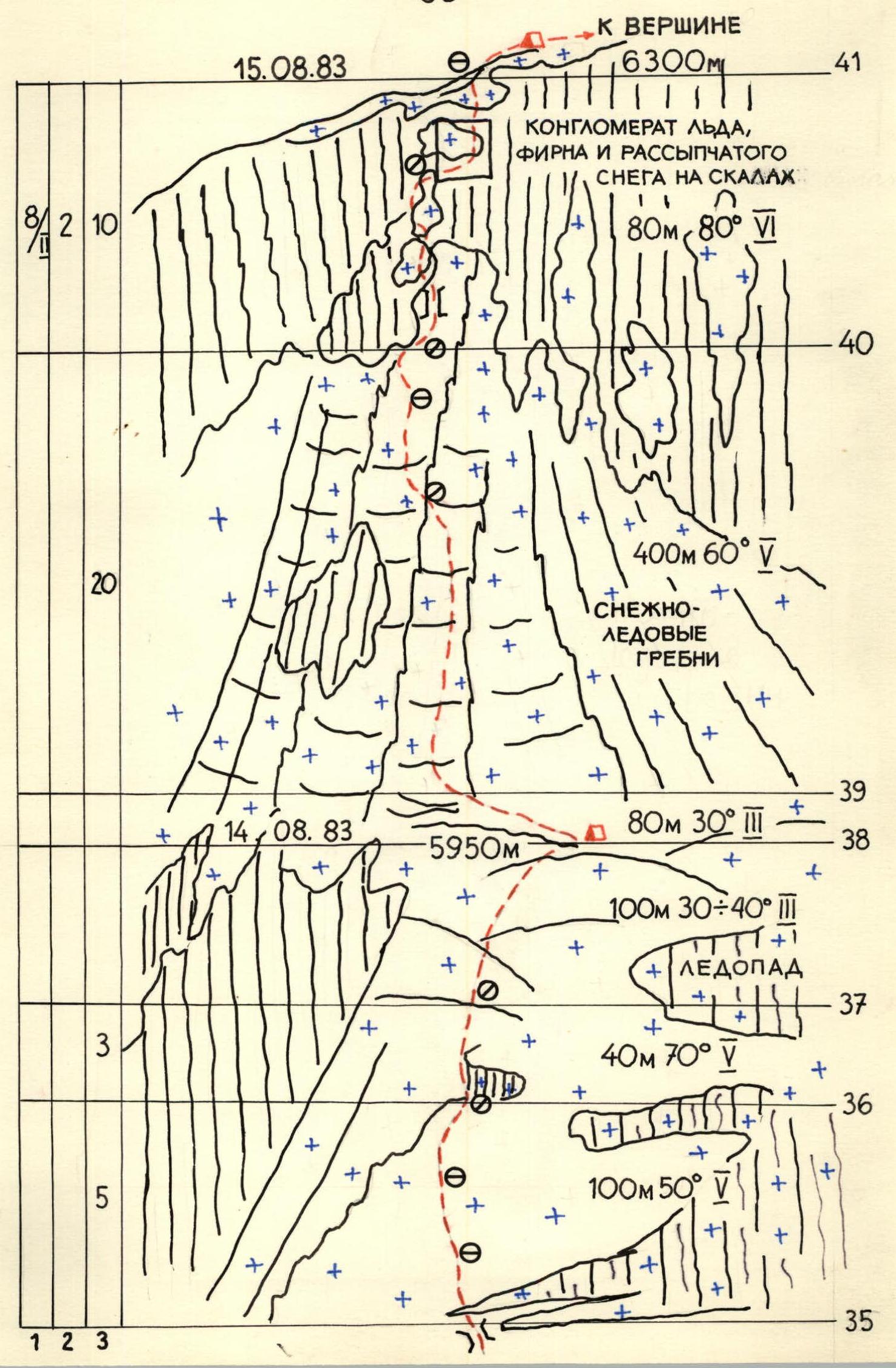

Profile of the wall on the left. Point 5 from Verblud, July 18, 1983, 10:00, h ≈ 5000 m, Zenitar 50 m, F = 50 mm.

Photopanorama of the area. Point 4, July 16, 1983, 14:00, h ≈ 5100 m, Zenitar 50 m, F = 50 mm.

Route Description by Sections

-

300 m 30°. From the glacier, the ascent follows a distinct snow-ice cone. The snow alternates with ice, a result of the cone being formed by upper hanging glaciers. When moving, it's advisable to stick to the right part, protected from rocks by the cliffs.

-

10 m 80°. The bergschrund was pronounced this year, and the first challenging section was navigating it. The passage was complicated by loose snow under the bergschrund.

-

60 m 45°. Movement on ice towards rocky outcrops to the right and upwards.

-

40 m 50°. Movement along ledges interspersed with walls. Hazardous! Abundance of loose and falling rocks. The rock type is black shale.

-

100 m 60°. Initially, ascent is along cliffs covered with marble powder and debris, moving rightwards along the wall, then straight up. Climbing is complex and hazardous due to weak, heavily weathered marble rock. Handholds break off under minimal load. Further ascent involves traversing leftwards on ledges.

-

70 m 75°. The wall becomes steeper, but the rock is more reliable. The next rope goes up a faintly visible ledge to the right, then up the cliffs resembling "ram's foreheads."

-

20 m 50°. A moderately difficult rock climb leads to a potential bivouac site.

-

100 m 45°. The trio of Boyko–Ryabov–Efimov begins processing a snow-ice ridge. At the point where the ridge breaks, they decide to set up a bivouac, for which they carve into the snow-ice ridge to create a safe platform above the rock face, somewhat protected from falling rocks.

-

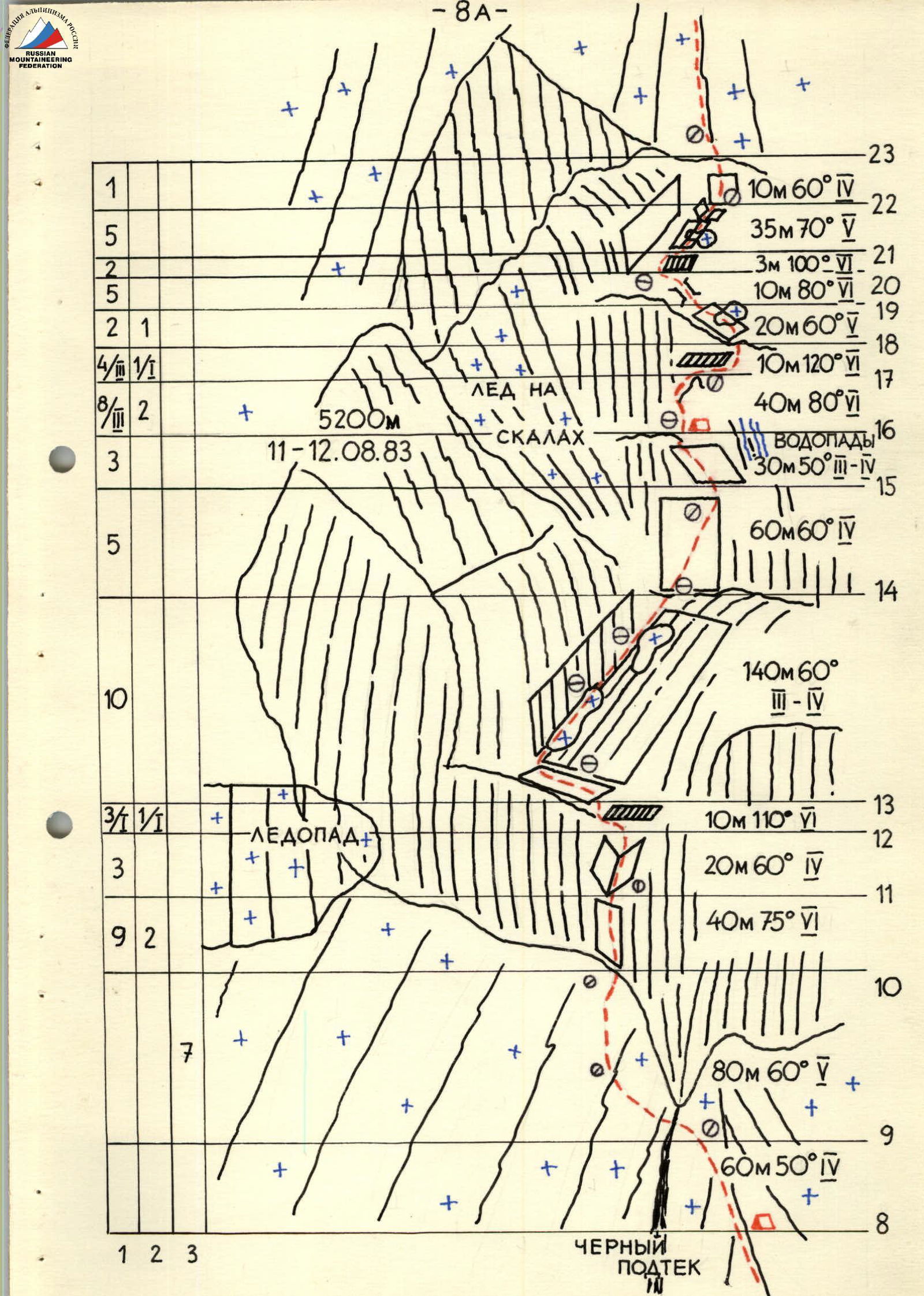

60 m 50°. The ridge steepens, becoming pure ice in places. They approach a rock wall. A direct ascent is problematic; they attempt to find a path to the left where the terrain is more dissected.

-

80 m 60°. Traversing one rope length leftwards under the rock wall on an icy slope (porous ice). It's challenging; they use ice screws in combination with an ice axe. They cross several gullies with dark stains from rockfall, a hazardous area. It's advisable to pass through before 10:00. Further ascent is straight up under the cliffs.

-

40 m 75°. Extremely difficult climbing on a faintly visible internal angle, more like a wall with a depression. The rock is steep and heavily weathered.

-

20 m 60°. The internal angle becomes more pronounced and gentler until it meets a cornice.

-

10 m 110°. They traverse the cornice to the left. Climbing is very difficult, risky in places due to rock degradation. Ryabov overcomes this obstacle by alternating between free climbing and using artificial aids and ladders. Kalagin, who was placing pitons, faced particular difficulty due to constant pendulum swings.

-

140 m 60°. Initially, they move left along a ledge, then along a rocky slope with occasional snow patches, rightwards and upwards along the wall. Despite an overcast sky, streams run down the walls, providing ample drinking water.

-

60 m 60°. From the rocky ledges, they move right onto a black shale wall. The rock is very soft and heavily weathered. It's snowing. Four team members prepare for the night, while the pair Ryabov–Lapin proceed to process the wall further. A waterfall is visible 20 m to the right of the ledge, which supplied them with about 50% of their water needs; the rest was collected from snow the following day.

-

30 m 50°.

-

40 m 80°, 10 m 120°. Directly above the tent, a complex wall ends in a cornice. Ryabov manages to climb one rope length under the cornice, pass beneath it, and emerge onto a rocky slope partially covered in snow in 4 hours. It's snowing. The snow intensifies by night, and they fall asleep in a blizzard. They dig out the tent several times during the night.

The snow continues into the morning, subsiding only by 13:00. Everything is white, like winter. The sun appears at 15:00. Everything is melting. The pair Boyko–Lapin proceed to further process the wall. By the end of the day, they've passed another cornice (see section 21), making it a total of 1.5 rope lengths for the day. The pair returns to the tent by 20:00.

-

20 m 60°. The slope is heavily snowed in. It's very difficult to find a spot for protection and fixed ropes. The path goes left and upwards towards an ice-filled chimney.

-

10 m 80°. The chimney leads to a cornice, beneath which is an excellent stance for protection. It's comfortable to belay while seated, having removed the backpack.

-

3 m 100°. The cornice is overcome on its left side where it meets the wall. Very difficult climbing, but at least there's no snow on the rock of the cornice.

-

35 m 70°. The path continues along a rocky slope near the wall. The ledges are snow-covered, and the rock is icy.

-

10 m 60°. Directly up relatively easy rock to a patch of flow ice. The temperature is clearly below zero. The ice is firmly cemented to the rock, and the rope doesn't dislodge many rocks.

-

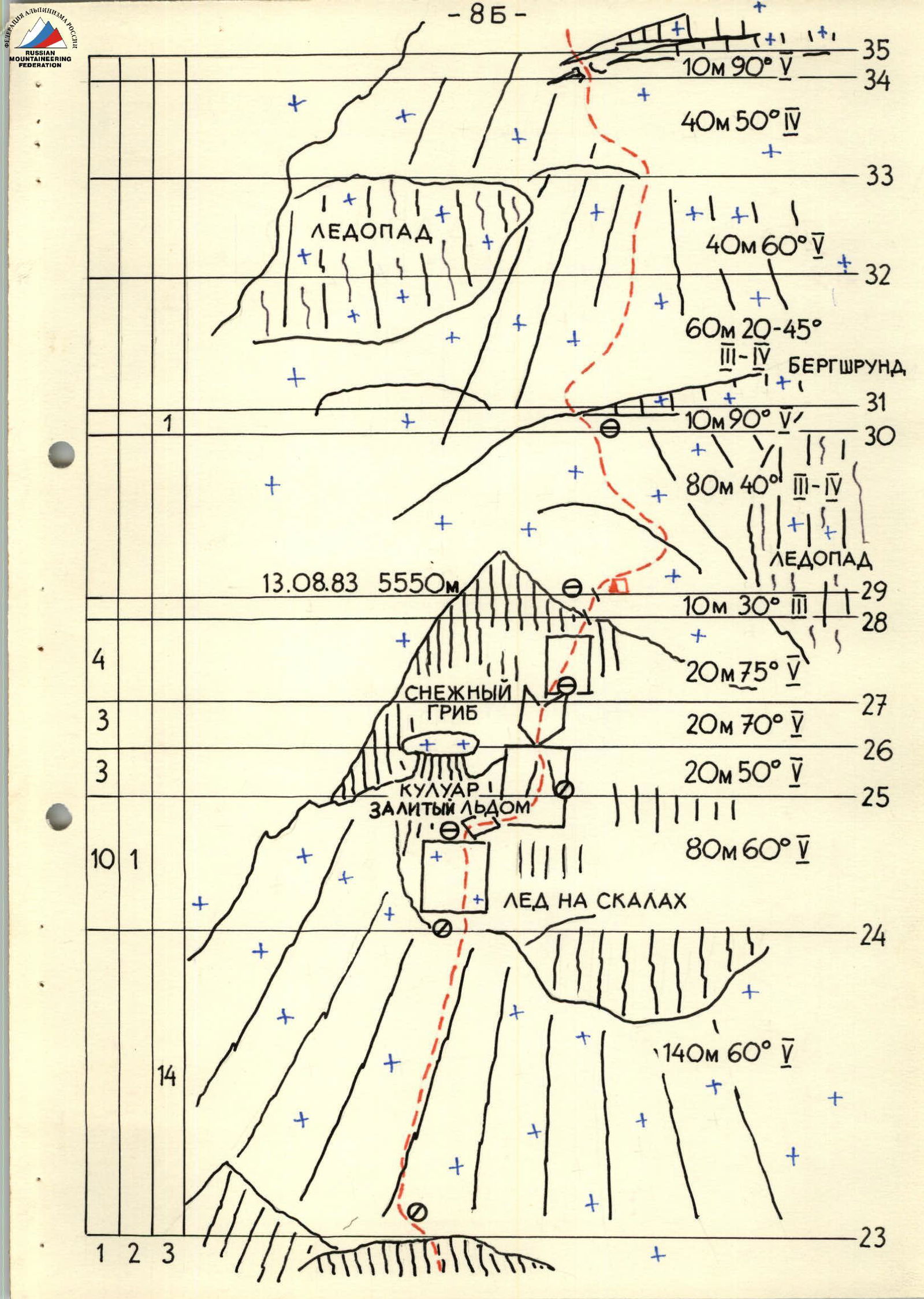

140 m 60°. The ice slope consists of g) and (f) channels separated by ridges of firn and loose snow. The optimal method to ascend this slope is to move along the edges of the gullies, establishing protection points on the ridges. They move directly upwards towards the cliffs.

-

80 m 60°. The cliffs are icy. The rope goes straight up to a snow "mushroom" on a rocky outcrop. Further right along a ledge into a wide couloir. The cliffs are icy; very difficult. The couloir transitions into an internal angle that meets a rock wall. It's snowing again.

-

10 m 30°. The rock wall ends, and they emerge onto snowfields above the lower right serac. They set up a tent and sleep lying down.

The next day, they move across the snow, which is quite steep and loose. Since snow conditions vary greatly from year to year and even month to month, they note the main difficulties encountered:

-

10 m 90°. The lower right serac is separated from the snowfield by a traverse left across vertical ice.

-

40 m 60°. A rope length of difficult and hazardous climbing on steep snow. The entire length of the ice axe is plunged into snow, with protection solely through the ice axe.

-

10 m 90°. Another ice gap. They cross a crevasse on a fragile snow bridge, traversing upwards and rightwards along an ice wall.

-

100 m 50°. A steep snow, then ice slope. Very challenging climbing on snow on ice, then on pure steep ice. The general direction is towards the summit. They bivouac on a gentle snow slope above the serac.

-

40 m 70°.

-

80 m 30°. Movement leftwards onto ice gullies with "krovavyi mal'chiki" (bloody boys) between them. They had heard about "krovavyi mal'chiki" at Suloev's clearing. They observed them through a telescope and binoculars, and now they could see them up close. "Krovavyi mal'chiki" are a conglomerate of firn (F), ice (I), and powder snow (S), formed through dry sublimation and subsequent crystallization. Layers of F, I, and S are mixed in all directions, taking on the most bizarre forms.

-

400 m 60°. Initially, they move along one of the ice gullies, sticking to its edges and trying to establish protection points on rock outcrops or the opposite edge of the gully. The higher they ascend, the steeper and harder the ice becomes. The general direction is leftwards towards a depression in the ridge.

-

80 m 80°. The ridge is distinctly felt. They see cornices hanging towards them, but the path to the ridge is blocked by "krovavyi mal'chiki," which they cannot bypass. Here, neither ice axe nor Ice Fi Fi finds a hold. Feet search for a foothold, digging deeper into the slope and causing snow to avalanche. Sections of ice are welcomed as a respite. The difficulty of this section is evident from the fact that it took 2 hours to climb the first rope length. They managed to establish a protection point on an ice section of the wall. After another rope length of equally challenging climbing, the lead climber emerges through a cornice and secures the rope on firn. The pre-summit fields begin. Although there's still 400 m of snow slope to the summit, it's a victory! The North face is climbed after two unsuccessful attempts.

-

400 m 20°. In the morning after a bivouac in a hollow, they reach the summit. They retrieve a note and a pennant left by a Czechoslovakian group in 1978.

Descent. From the summit, they first follow the ridge, then move left along the route into the snow-ice cirque of Peak Radionova. Further ascent follows a depression in the western ridge of Peak Radionova, and from there to the Shini-Bini pass. On the descent, there's a risk of avalanches and hidden crevasses. From the Shini-Bini pass, they descend towards the Fortambek glacier, keeping to the left side of the slope. Hazards include:

- Rockfall

- Individual rocks falling from water streams

Technical photograph of the upper part of the route. Point 3, August 15, 1983, 11:00, T-50, F=50 mm.