Report of the Sverdlovsk Region team on the ascent of Poisenot Peak

Climbing passport □

□□

□

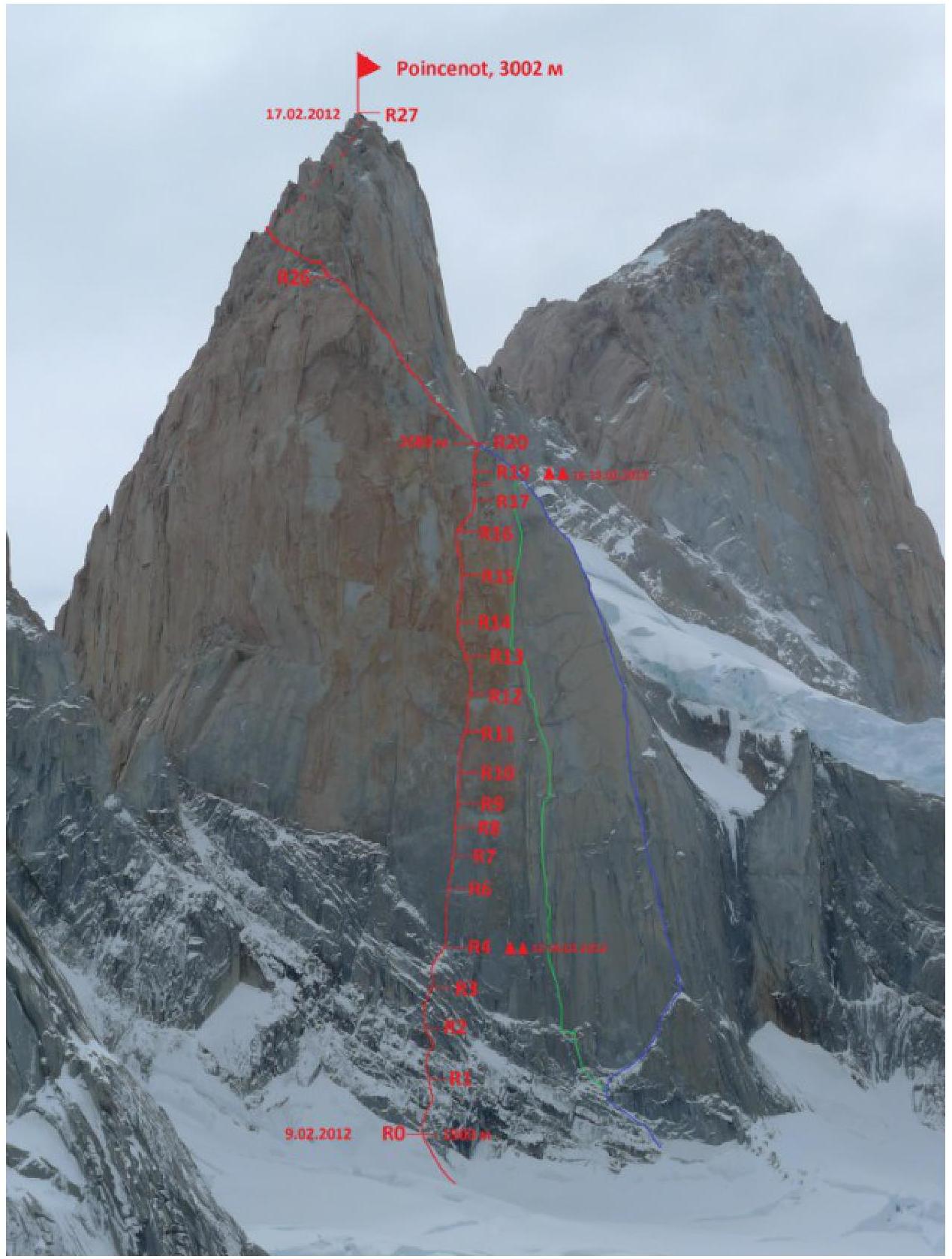

Route description

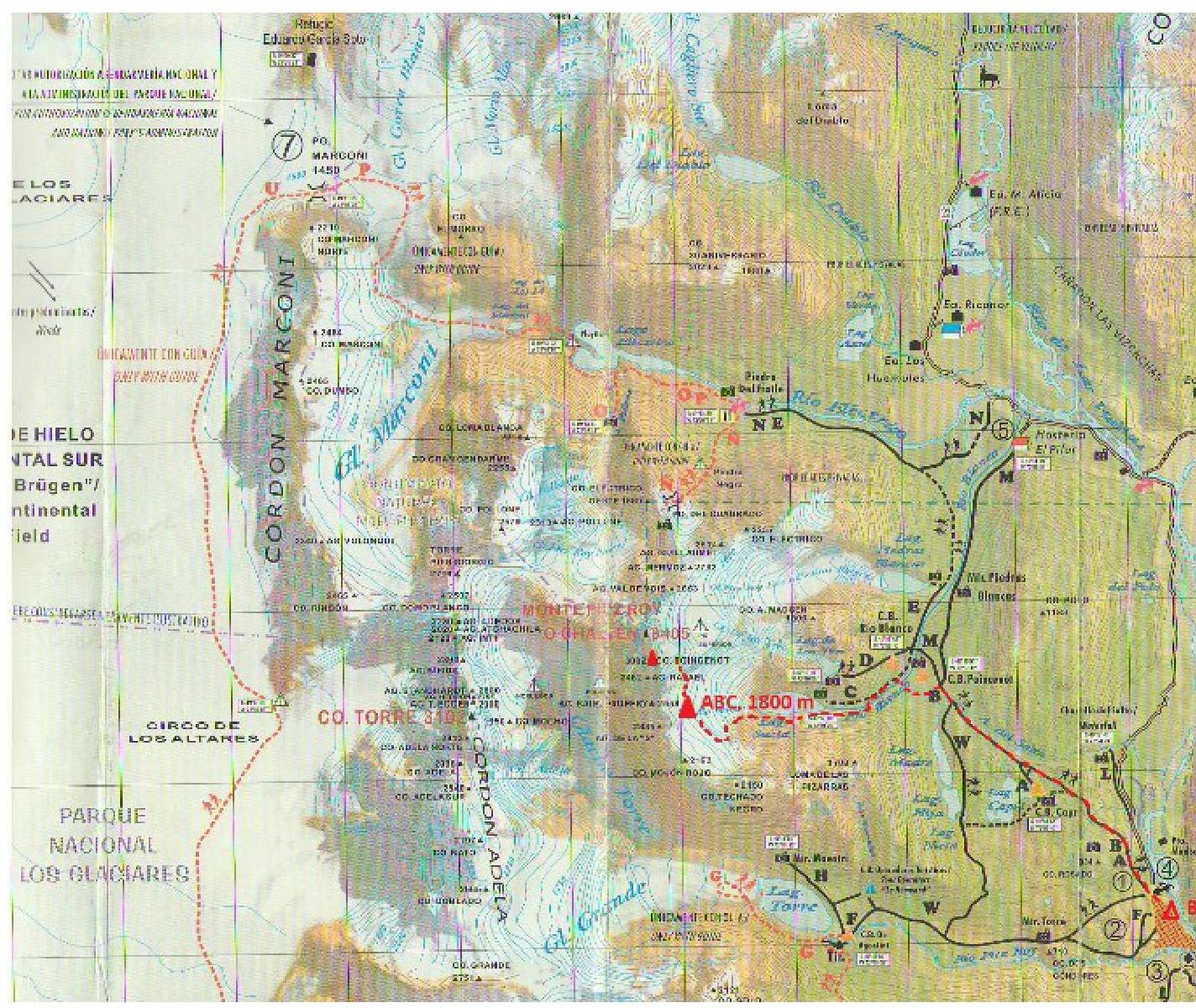

From the base camp in El Chaltén (400 m) follow a well-marked trail to Poisenot camp (700 m) — 2–2.5 hours. Then turn left and move along the trail towards Lago Suchiá — 1–1.5 hours. Bypassing the lake on the left, ascend the moraine to a rock cave (1400 m) — 1.5 hours. From the rock cave, move upwards for 1 hour to a visible saddle (1700 m). Here, it's necessary to rope up. Further:

- Cross a heavily crevassed glacier, sticking to the left side, and approach the southeastern wall of Poisenot Peak.

- A snowdrift under Poisenot Peak is a convenient place for ABC in a snow cave (1 hour from the saddle via a pre-laid path).

- The start of the route is under a well-visible system of cracks in the central part of the wall (start at 1900 m) — 1.5 hours from the cave.

Section R0–R4:

- Length: 200 m.

- Category: 6B (fr 6a–6b), M4.

- Move along a logical system of small walls and snow-covered inclined shelves towards the base of a well-visible vertical crack system.

- Climbing is complex: inclined shelves alternate with vertical, sometimes overhanging walls.

- Many cracks are filled with ice.

- Double-rope technique is required due to numerous traverses left-right.

- At the end of R4, there's a convenient bivouac site.

Further, it's necessary to fix ropes on the entire wall — there's no place to overnight on the wall due to strong winds and lack of shelves.

Section R4–R6, length 50 m, A2/A3. Along a double system of cracks with destroyed walls — tense ITO vertically upwards. Starting from this section, the route:

- is uncompromisingly overhanging

- doesn't lose steepness until the exit to the ridge

Section R6–R7, length 30 m, VI (fr 6b). Along a system of slots with destroyed walls — tense climbing in the direction of a vertical inner corner

Section R7–R10. Length 90 m, VI (fr 6a–6b), A2. ITO along an inner corner with periodic complex sections. The inner corner is vertical, sometimes snow-covered, with little relief

Section R10–R11. Length 50 m, A3. Exit from the inner corner to a monolithic wall. Station under a cornice. At the time of passage, the relief was heavily snow-covered, making free climbing impossible

Section R11–R12

- Length 100 m, A2–A4

- Move along monolithic relief on skyhooks towards an overhanging inner corner. Insurance is problematic

- Further along the corner to a large cornice

Section R13–R14

- Length 50 m, A3–A4

- Traverse left 10 m under the cornice to an inner corner

- Relief is poor; it's more convenient to traverse along a monolithic wall on rock hooks

Section R14–R16. Length 85 m, A3–A4.

- Pendulum right into a neighboring inner corner.

- The corner soon turns into a dead-end slot, which soon disappears altogether.

- Further, move along a monolithic overhanging slab upwards-left.

- Movement on rock hooks.

- For insurance, periodically encountered fragile flakes were used.

- Station on a small shelf.

On these ropes, it becomes very windy, as the saddle between Rafael Peak and Poisenot Peak is lower.

Section R16–R18. Length 80 m, A3–A4.

Along oblique shelves and complex walls with poor relief, move right-upwards towards a visible system of corners — chimneys in the direction of the ridge.

At the end of R18, there's a convenient overnight site.

Section R18–R20. Length 70 m, VI (fr 5+/6a), A1.

Along a cornice turning into an inner corner, exit onto the ridge (height 2680 m).

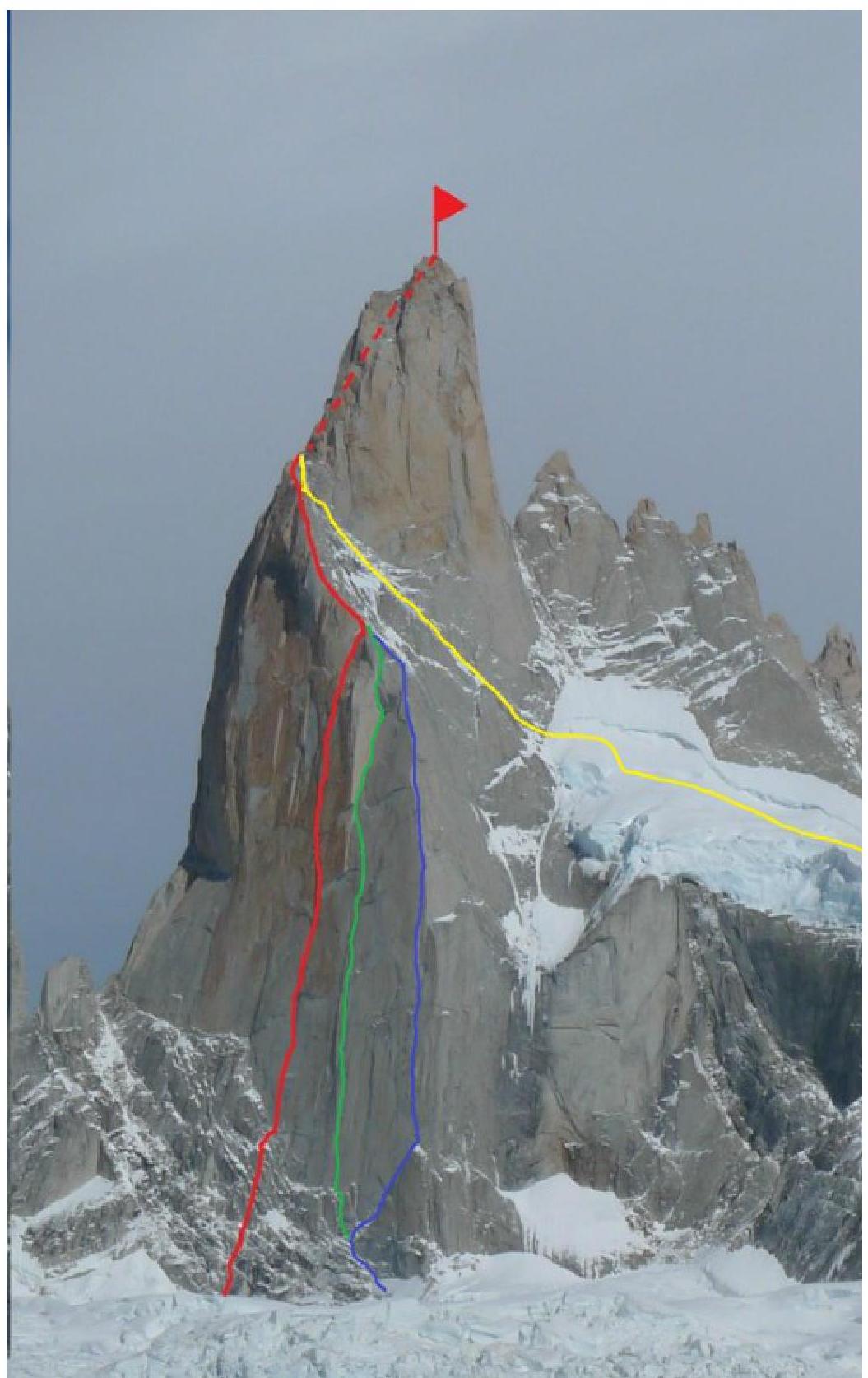

At this point, the route joins the Italian route of 1986, Speroni degli Italiani.

Section R20–R26. Length 300 meters, V–VI (fr 5–6b, M3). Move along the ridge towards Poisenot's shoulder. The ridge is quite steep. Many traverses and complex walls. We highly recommend using rock shoes.

Section R26–R27. Length 500 m, V. From the shoulder, the route coincides with the classic route climbed by an Anglo-Irish team in 1962. Movement is constantly left-upwards. Many traverses and climbing of medium complexity on walls of medium steepness. Exit to the summit of Poisenot (3002 m).

Descent along the ridge — Speroni degli Italiani route. The descent route is logical and safe. Many hooks and loops can be found for organizing the descent.

However, in windy weather, rappelling can be extremely problematic due to:

- high risk of rope getting stuck.

Technical and tactical actions of the team

There are three aspects of tactical and technical actions of the team on a new route:

- choice of the route itself

- choice of the schedule and style of movement along the route

- technical techniques used on the route

The choice of the route was determined by two factors. On one hand, despite the fact that the Fitz-Roy massif is quite well explored by climbers (19 routes have been climbed on this peak alone), the Southeastern wall of Poisenot Peak remained practically unclimbed, with only two routes existing on its far right part. There were no attempts to climb the central part of the wall, so steep and inaccessible did it look. The middle part of Poisenot's SE wall is the steepest wall in Patagonia, including the walls of Cerro Torre and Fitz-Roy. On the other hand, we saw a logical system of cracks on the wall with small links on monolithic rocks, which allowed for a route with maximum use of natural relief. Another important factor was the objective safety of the route, absence of hanging seracs and destroyed rocks above it. The only danger could come from the famous Patagonian bad weather, which could turn any ascent into a struggle for survival in a matter of hours.

Accordingly, the style of ascent was chosen based on the established weather and the chosen route. Such complex routes are not typically climbed in the modern fast and light style; nor did we want to climb in the traditional Patagonian siege style — when the entire route is fixed from bottom to top from a comfortable snow cave over a month or two, or sometimes several seasons, and then the team reaches the summit in one good day. The traditional capsule style remained — overnight stays on relatively comfortable and, most importantly, safe platforms, and fixing a few ropes to reach the next safe overnight site in one day.

There was no time to wait for good weather; we had to climb:

- in rain,

- in snow,

- under hurricane-force winds.

Technically, movement along the route was organized in a way we had mastered on numerous wall ascents:

- the first climber moved on a double rope (one 1 UIAA, the second ½ UIAA);

- the second climber followed on the fixed rope with top insurance and replaced the fixed rope with a 10-mm static rope with dynamic properties.

Despite the objective rockfall safety of the route, movement of the rest of the team on fixed ropes was typically also done with additional insurance using a second rope.

When moving as the first climber, the entire arsenal of modern technical techniques was used — maximum use of free climbing with filigree use of ITO — mainly on cams, micro-cams, and anchor hooks.

Sections of monolithic rocks were climbed on skyhooks with rare insurance points organized on:

- micro-relief,

- removable bolt hangers.

Stationary bolt hangers were hammered (and left) only at overnight sites, for hanging platforms, and only one was hammered at a station when other equipment ran out.

The choice of leader was made considering the prevailing character of the route section:

- Sections climbable by free climbing up to 7th category were climbed by Dashkevich;

- On sections climbed on ITO with predominant use of anchor hooks and skyhooks, Dmitrienko worked mainly;

- The section of destroyed rocks on cams was climbed by Dave.

The complex of the above-described tactical actions allowed the team to accomplish the planned and successfully climb the route, which became the first Russian big-wall route in all of South America! This route is undoubtedly the most complex route on Poisenot today and is comparable in technical complexity to the most complex routes in Patagonia, such as the "Devil's Directissima" on Cerro Torre. At the same time, the route was climbed in unstable weather in a very good schedule — just 5 days from departure to the summit.