Ascent Log

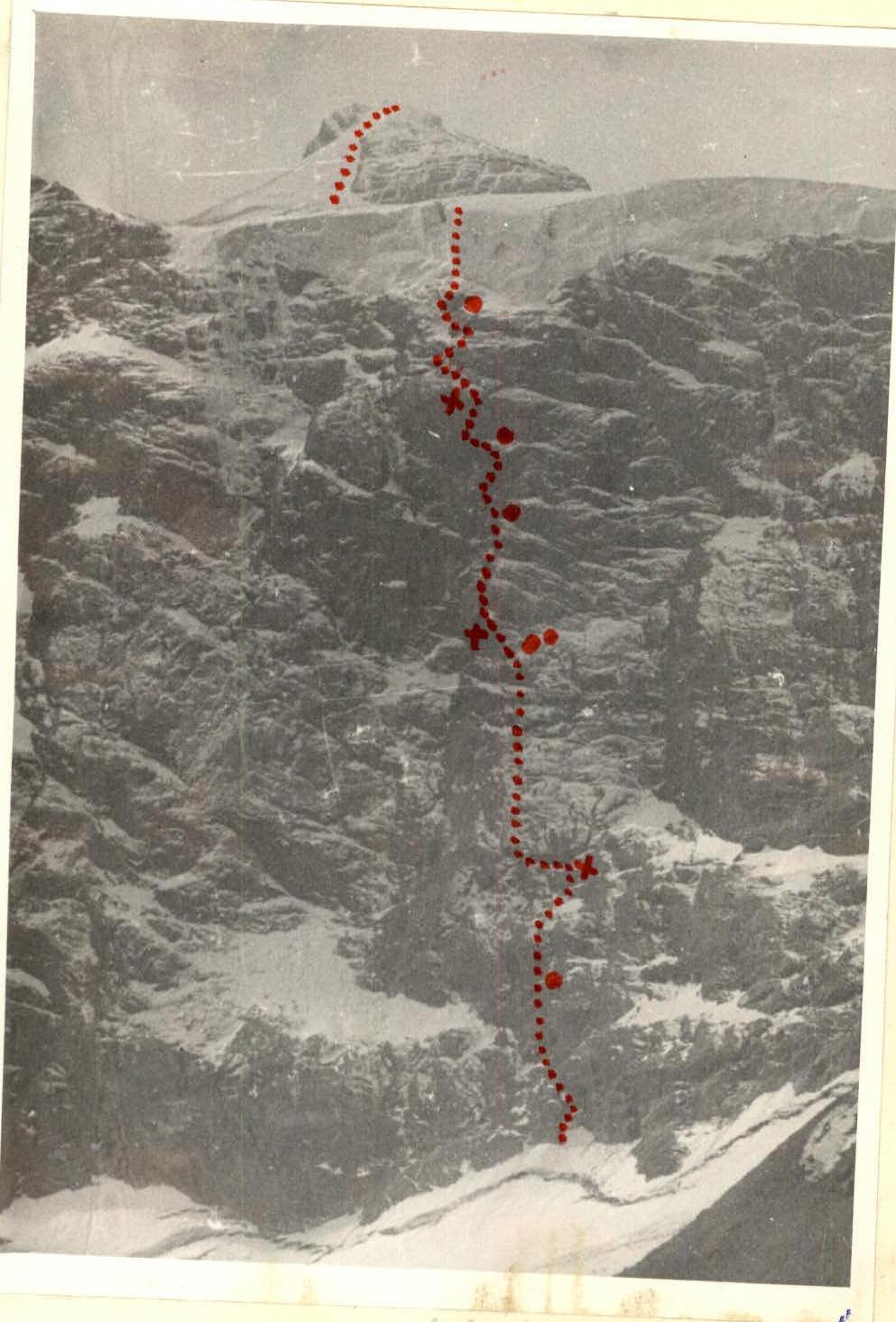

I. Ascent Class — Technical 2. Ascent Region — Fan Mountains 3. Peak — Moskva, 5183 m via the north wall through the hanging glacier 4. Anticipated Difficulty Category — 6B 5. Route Description:

Total height difference — 1480 m. Characteristics of the wall section (rock and ice): height difference — 1290 m, including 131 m of ice wall, length — total — 1474 m, including 142 m of ice, sections of category V difficulty — 462 m, " — 15 m, category VI difficulty — 484 m, " — 95 m. Average steepness of the wall — 76°, including the lower part (270 m) — 62°, the remaining part (1010 m) — 79°, ice wall (106 m) — 92°.

- Equipment Used on the Wall Section:

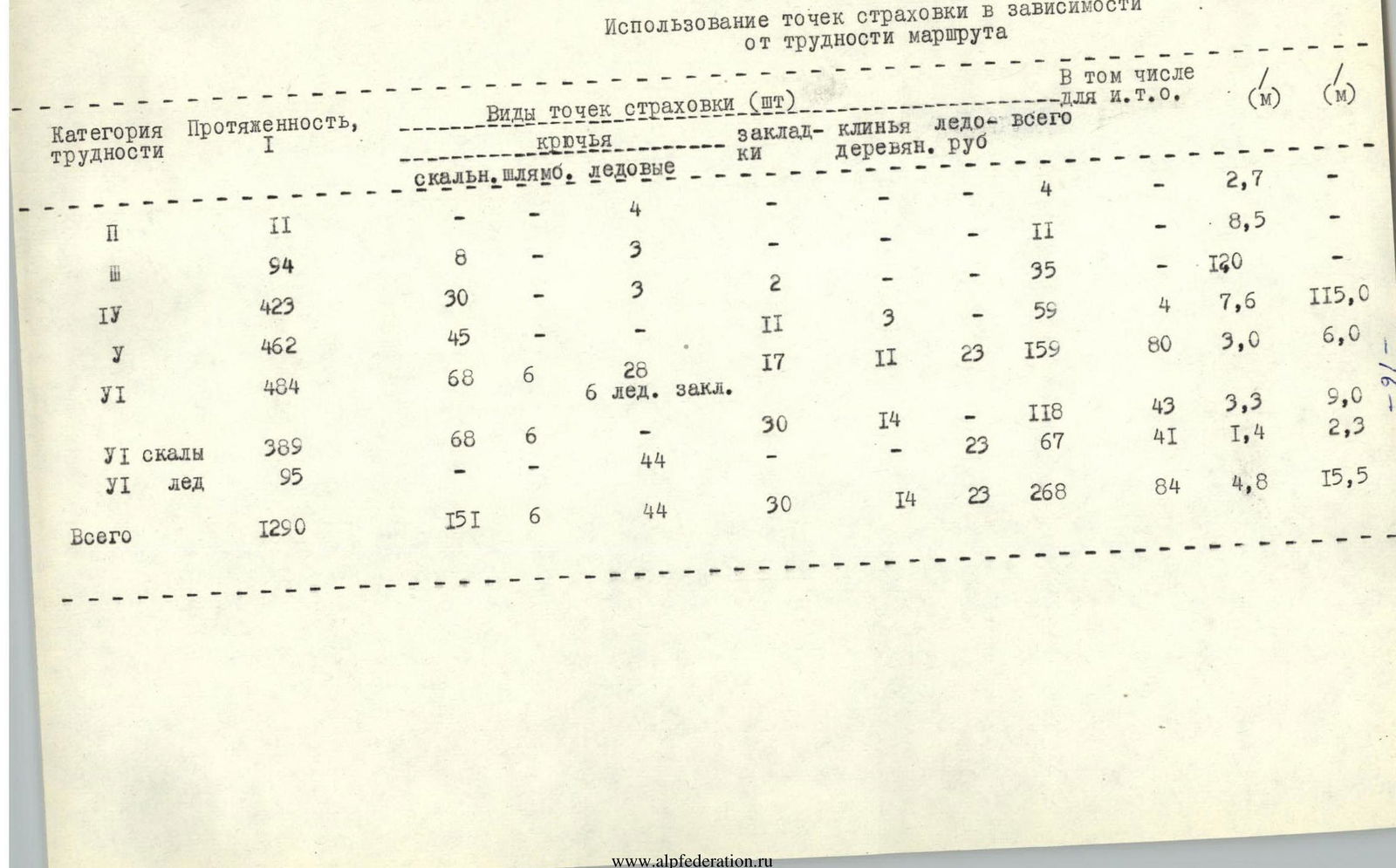

Total, including for creating I.T.O.img-0.jpeg

On the remaining part of the route, 3 ice screws were used.

- Number of Working Hours (on the wall) — 64 hours

- Overnights — 6, including seated — 4, hanging — 2

- Team Composition from "Artuch" Alpine Camp:

Shumilov Oleg Ivanovich, MS — captain; Chasov Eduard Izrailevich, MS — deputy captain; Parkhomenko Alexander Leontevich, MS — participant; Borodatsky Igor Grigorievich, CMS — participant; Ivanov Nikolai Rufovich, CMS — participant; Urodkov Anatoly Akindinovich, CMS — participant.

- Team Coach — Shumilov Oleg Ivanovich

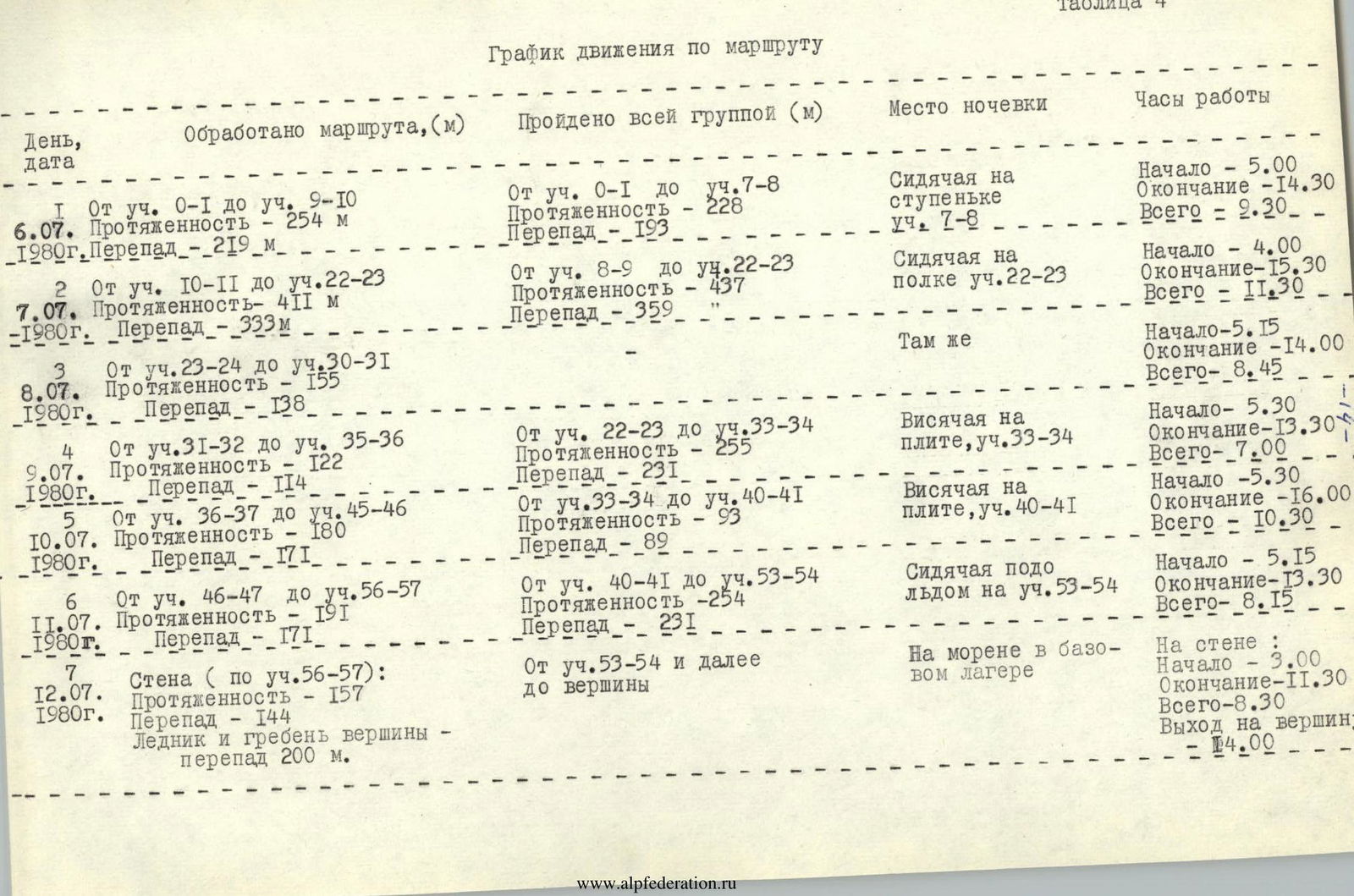

- Dates: departure on the route — July 6, 1980, ascent to the summit — July 12, 1980.

Total — 7 days

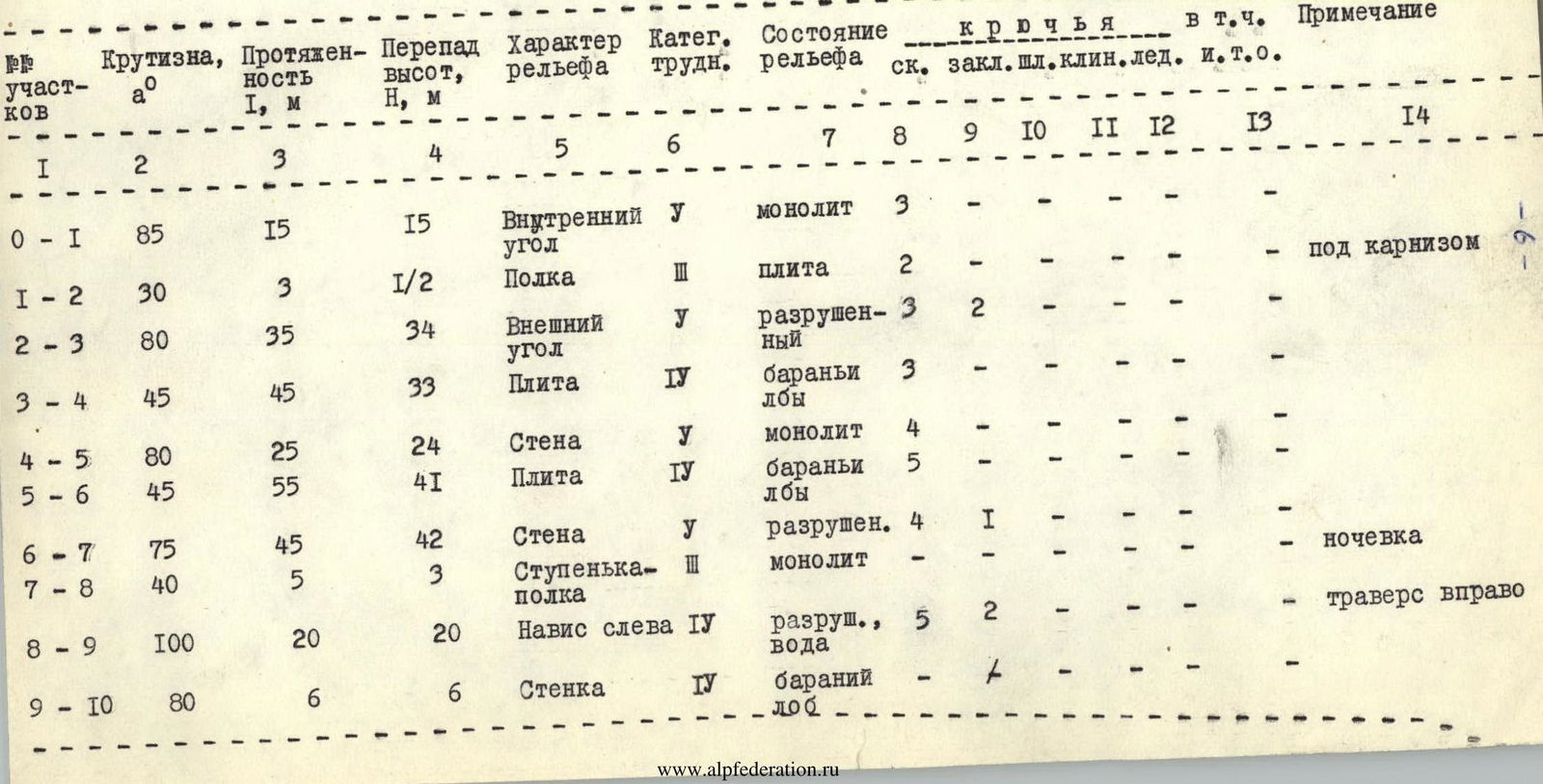

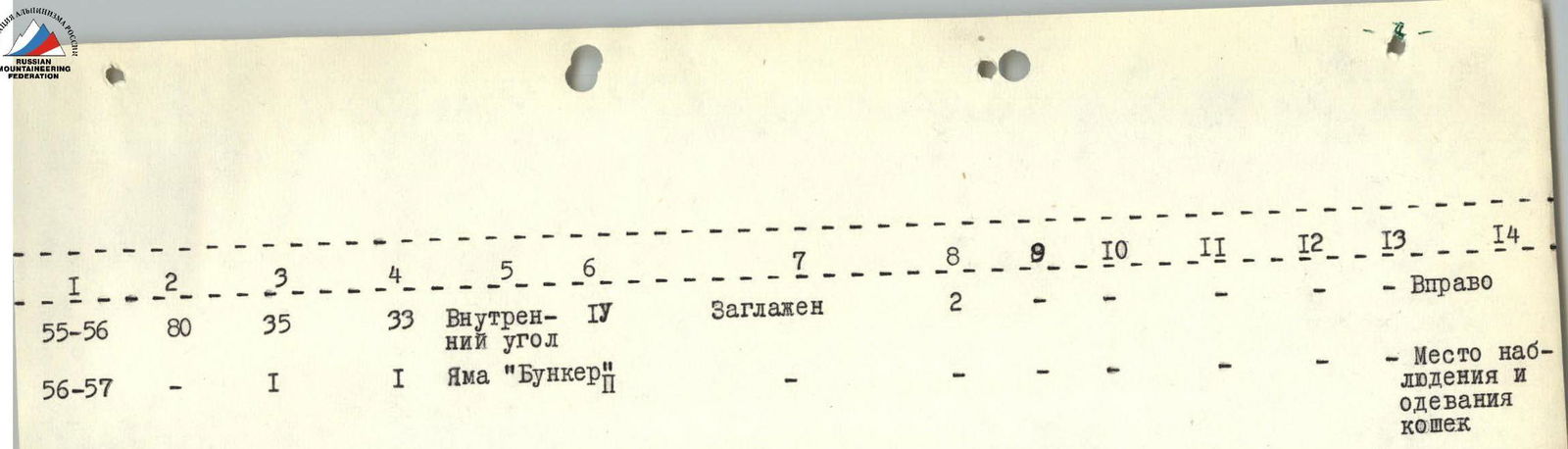

X) The steepness of positive sections was determined visually (in case of continuity of wall inclination on the route section and to the side of it); the steepness of negative sections — by the droop of the end of a free rope. Table 3

Main Route Characteristics

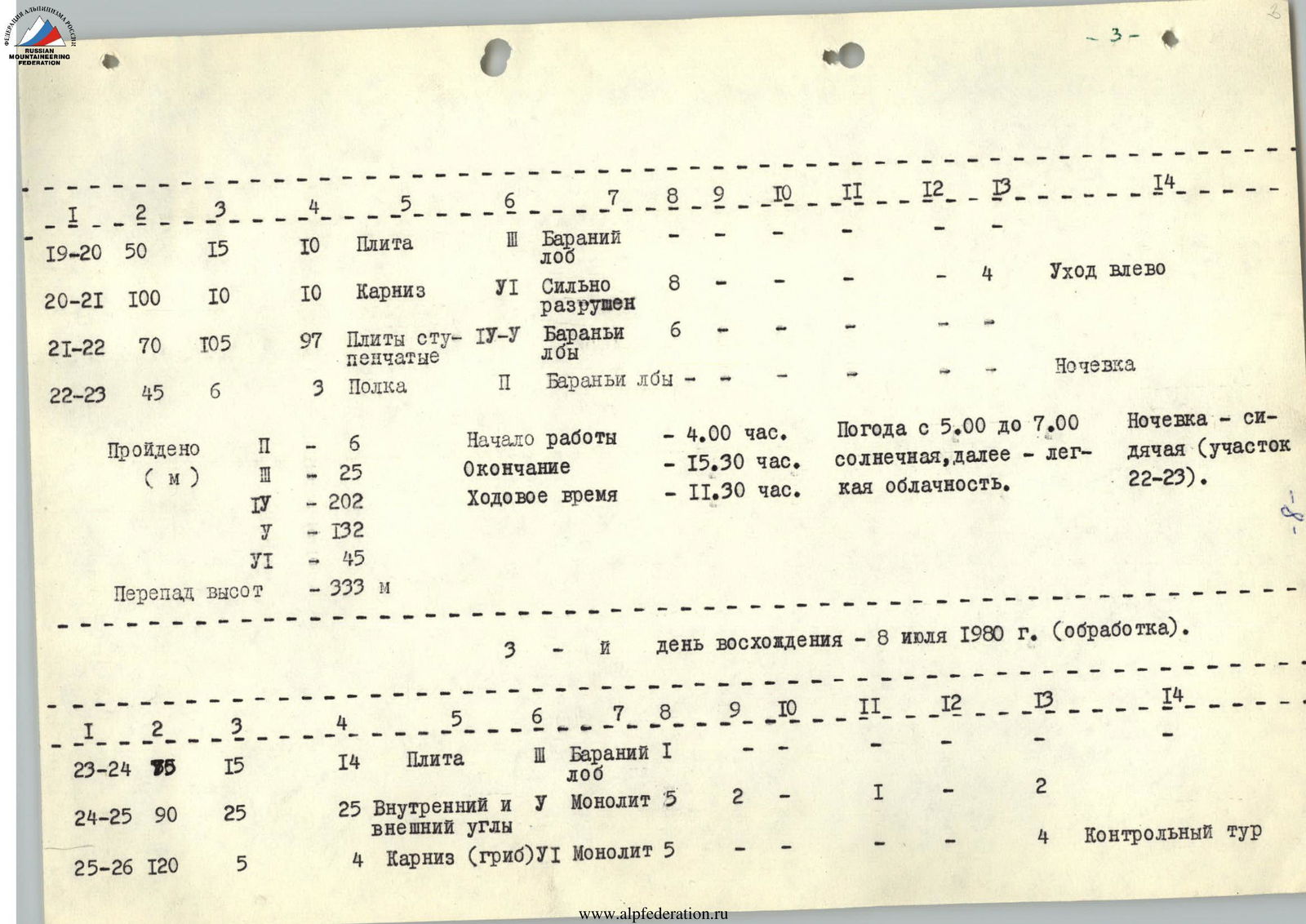

1st day of ascent, July 6, 1980

Distance covered

II — 8 m by cat. diff. — 126 m V — 120 m VI — total — 254 m. Height difference — 219 m.

Distance covered

II — 8 m by cat. diff. — 126 m V — 120 m VI — total — 254 m. Height difference — 219 m.

Start time — 5:00. End time — 14:30. Worked — 9 hours 30 minutes.

Weather from 5:00:

- Overnight stay seated until 9:00 — sunny.

- Then — cloudy. Temperature not below zero in the morning.

2nd day of ascent — July 7, 1980

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R0–R1 | 45 | 70 | 50 | Плита ступенчатая | IV | Бараньи лбы | 2 | - | - | - | - | - | |

| R1–R2 | 30 | 5 | 2 | Полка | III | Монолит | - | - | - | - | - | - | Контр. тур |

| R2–R3 | 70 | 35 | 6 | Плита | У | Зеркало | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | Траверс влево |

| R3–R4 | 100 | 20 | 20 | Карниз | VI | Монолит | 10 | - | - | - | - | 3 | |

| R4–R5 | 70 | 65 | 60 | Ступени | IV | Разрушенные | 4 | - | - | - | - | - | |

| R5–R6 | 60 | 20 | 17 | Плита | III | Монолит | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | Траверс вправо |

| R6–R7 | 95 | 15 | 15 | Стенка | У | Монолит зализанный | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | |

| R7–R8 | 70 | 30 | 28 | Внутренний угол | У | Разрушенный, лед | 1 | 2 | - | 1 | - | 1 | «V»-образный |

| R8–R9 | 100 | 15 | 15 | Карниз | VI | Сильно разрушен | 8 | 1 | - | 1 | - | 3 |

| Пройдено (м) Перепад | R1–R0, R1–R2 | Начало работы | −5:30 Окончание | Погода — с утра чистое небо, с 14:00 — сплошная облачность, | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Рабочее время — | 7:00 | ветер резкий, холодный, порывистый. |

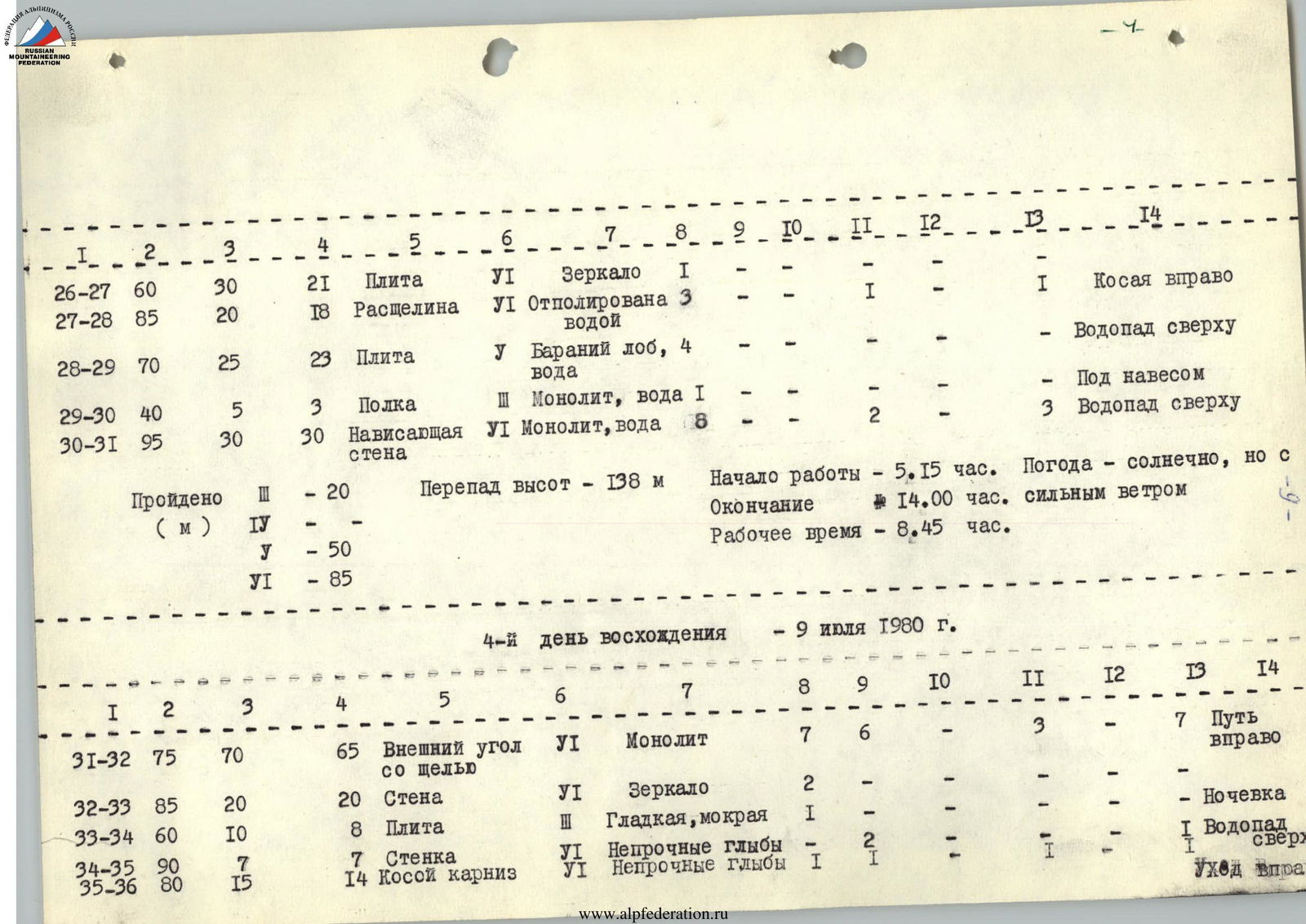

5th day of ascent, July 10, 1980

Пройдено (м) R1–R3 III–15 Начало работы Окончание

Movement schedule on the

route Table

5. Wall length by categories

Table

5. Wall length by categories

| Day of ascent | Wall height difference, H | Wall length by categories (m) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| II | III | ||

| 1 | 219 | - | 8 |

| 2 | 333 | 6 | 25 |

| 3 | 138 | - | 20 |

| 4 | 114 | - | 10 |

| 5 | 171 | - | 1 |

| 6 | 171 | 3 | 15 |

| 7 | 144 | 2 | 15 |

| incl. ice | 131 | 2 | - |

| Total | 1290 m | 11 | 94 |

Use of protection points depending on route difficulty

II. Ascent Tactics and Safety Organization.

Combined routes that combine "sixth-category" rocks and "hanging glaciers" with vertical and negative ice require complex tactics when passing, different from those used for usual "sixth-category" ascents. The basis of this tactics, in addition to ascent experience, is the knowledge of certain physical patterns governing the layering and separation of ice and ice blocks, their fall, and transformation, which can be identified and assessed through careful study of experience.

The tactics for passing these combined routes could not be proposed immediately. Their development was preceded by prolonged observation of the behavior of other similar peaks, such as Moskva, and experience gained by team members in traversing hanging glaciers like Mirali and Maria.

The preliminary part of the tactical plan involved a multi-day thorough reconnaissance, determining the ice regime and fall patterns, identifying the optimal time for traversing the wall as a whole and the ice in particular, and selecting overnight locations. Reconnaissance of the wall began in 1978. At that time, the principal feasibility of overcoming the wall through the ice in the center was established, which was accomplished that year. This year's observations and interviews with people allowed us to determine that ice falls typically do not occur between midnight and 16:00, and are rare, not more than once every three days. No recent falls were observed near the intended route. However, all this was noted for relatively stable weather and temperature conditions. Significant temperature fluctuations could alter the hanging glacier's behavior. The team started the ascent after a period of warm, sunny weather, during a relative "deterioration" of weather coinciding with the new moon in the Fan Mountains. Before and during the ascent, there was average cloud cover; according to weather forecasts, the average daily air temperature dropped by 3–4°C. Thus, the team was climbing under conditions where, following a warm spell, there was a relative "unloading" of the hanging glacier, i.e., the release of its particularly unstable parts, followed by the consolidation of the remaining non-monolithic material.

The plan also considered that falling ice in the lower part of the wall breaks into shards and turns into ice chips and dust. The latter poses a negligible danger, as it cannot cut a rope. Falling ice does not ricochet.

The prevalence of slabs and walls on the slopes, which have been under water flows for a long time, makes it unlikely that free stones are present in ice falls (this is confirmed by studying the debris cones of ice falls).

Hazards may include:

- Suspended ice dust posing a risk to respiratory tracts.

Observations showed that during ice falls, due to the ice being saturated with water, the dust cloud dissipates in less than a minute, and it is sufficient to cover one's head with a windbreaker to wait it out.

Melting of the glacier along the entire wall causes the appearance of water flows. Their transformation occurs in two directions:

- Spraying of jets and transfer of this water mist along the entire wall, including under overhangs;

- Formation of rime ice at night and its preservation on non-sunny days in the upper part and in shaded areas for most of the day.

Based on the above, the wall traversal tactics included the following provisions:

- Maintaining a vertical route line with deviations only to avoid large overhangs or to organize safe overnight stays.

- Choosing a route direction to minimize sections exposed to ice and rock impacts.

- Traversing the route through difficult, complex, but safe rocks and ice.

- Early rise and work on the wall until 14:00–15:00. An exception was made for the upper part of the wall, where the team was protected not by individual overhangs but by entire sections of the wall (practically, work on the wall began earlier than 5:00 am every day).

- Organization of belay points exclusively under overhangs (not only on rocks but also on ice); traversing the lower part in a "run-and-stop" manner from overhang to overhang (or from one negative section to another). When traversing open sections, team members were encouraged to move at full strength. To increase freedom of movement on some sections, movement was done with self-belay on a sliding carabiner with additional belay (mainly from above).

- Preliminary processing of the route by free team members in safe locations. A particular case of this provision is returning to safe overnight stays.

- Organization of overnight stays exclusively under rocky overhangs. All overnight stays were seated or hanging. For this, the necessary bivouac equipment was taken.

- Strengthening, compared to common practices, the belay systems for the group as a whole and for each team member personally. To implement the above provisions, sufficient rope (8 pieces of 40 m, including two imported high-strength ropes, 2 of 80 m), pitons, and other equipment were used.

Additional collective safety measures included:

- Moving on double ropes or on single ropes with belay;

- Securing the ends of ropes at three points and blocking them;

- Coupling ropes;

- Introducing intermediate rope attachment points;

- Securing tent ropes on overnight stays with pitons.

The team applied checking and re-checking of all organizational systems by team members, enhancing their reliability and completely eliminating accidental errors (which could have occurred with practically several thousand operations and actions).

Personal additional safety measures included:

- Double self-belay on bivouacs and stopping points;

- An additional clamping device on the ascender;

- Independent attachment of self-belay, separate from the main ropes, to the self-belay chest carabiner;

- An additional belt (in addition to the "chest harness — leg harness" system) with its attachment to the main self-belay carabiner;

- Wearing helmets on overnight stays, among others.

-

Traversing the ice wall was planned to be done before 12:00 in the direction of the least fragmentation, after preliminary reconnaissance the day before. For the upper part of the hanging glacier, which was a firn layer, it was planned to use an ice axe and ice hammer, which was implemented practically. Ropes were attached to the monolithic ice, not to its fragments.

-

The presence of waterfalls and a continuous water cloud in the upper part of the wall, increasing in intensity when approaching the glacier, was taken into account. The group was psychologically prepared for this. In addition to increased difficulty in traversing such rocks, there is a higher risk of catching colds. Traversing such sections was done early in the morning before melting began, with thorough belay ensured.

Another aspect of the presence of water — the coating of rocks with rime ice almost until noon — was also taken into account by including "ice chocks" in the equipment.

X) There were no illnesses, injuries, or wounds during the ascent.

The ascent revealed:

- A high level of moral and technical preparation of the team;

- Exact adherence to the previously devised tactical plan, indicating both the correctness of the leader's actions and the team's overall performance.

The developed tactics for traversing wall routes with a hanging glacier above them fully proved themselves. They ensure safety equal to that of any classified route of the highest difficulty category.

III. Route Description by Days. July 4–5, 1980.

- We observed the wall and closely monitored its behavior.

- The route is unusual.

- Divided into pairs, we went out to inspect and photograph under the wall, on opposite slopes to the Dvoynoy Pass, and on the Amshuta ridge.

On the evening of July 5, at a general team meeting, we approved the final route variant, refined the tactical plan, specified the communication order, and adjusted the equipment and supplies.

First day — July 6, 1980. At dawn, the R0 pair, Shumilov — E. Chasov, was under the wall at the designated point. The snow had frozen overnight, making it easy to walk, and the bergshrund was easily crossed on a wide bridge.

We immediately began to storm the lower wall. After 15 m of an internal corner, we reached a triangular ledge, half a meter wide and three meters long. This was the first re-clipping point.

Today, the most experienced team members worked ahead — they were to:

- Put the tactical plan into action;

- Set the general direction for the ascent;

- "Feel" the wall.

Steep rocks (sect. R2–R3) led to a more gentle part — a pedestal. It consisted of uncharacteristic slabs and walls. In some places, fresh ice was on the rocks, and old ice lay in depressions. Today, the mental load was high — the first day is always tense; we moved slowly, carefully choosing the path under the upper overhangs. Landmarks included:

- Two overhangs (sect. R8–R9);

- Significantly higher — a cornice (sect. R13–R14).

We approached the first overhang, under which there was a small step-shelf like a "ram's forehead." It was quite comfortable and safe because the shelf was almost 5 meters long. The overnight stay was seated. The entire team gathered here. We found snow for drinking to the left, without leaving the overhang's protection.

Since there were overhanging rocks above (sect. R8–R9), we decided, despite the late hour, to hang another rope. We traversed to the right and passed:

- The overhang itself;

- Another wall.

Second day — July 7, 1980.

The route on the second day continued on a relatively gentle part, which, for safety, required intense work by the entire team. From the worked rope upwards, almost two ropes continued as "ram's foreheads." We reached a ledge (sect. R11–R12) located under a cornice (sect. R13–R14), which was visible from the glacier.

Under its protection, we set up control cairn #1. We could have stayed here overnight, but we tried to ascend higher, under the protection of the upper cornices.

We traversed the rope to the left to a gap formed by a piece breaking off during some earthquake and passed it head-on. For the first time, we used ladders in some places. To the right of the rocks, water flowed, remnants of night ice, but here we could move left away from it. The rocks were very smooth, with few cracks, making it difficult to find suitable spots for pitons, likely because ice and water had affected them in snowy years.

By noon, we passed one after another three cornices (sect. R16–R17, R18–R19, and R20–R21). It was impossible to bypass them as it would have required entering open and, as we saw, not less difficult (due to smoothness) rock sections. We had to hurry, especially on the last slabs (sect. R21–R22) before the overnight stay, which was planned from the glacier using binoculars (sect. R22–R23).

Our assumptions were correct — the ledge was on a convex part of the tower (it could not be hit by lateral falls) under a mushroom-like cornice (safe from above).

All participants moved with an additional rope. At half past three, A. Urodkov removed the last belay rope. The overnight stay was on a fairly long ledge (a series of steps), with tents hung in tandem in a not very comfortable location — close to the wall.

Third day — July 8, 1980. At the first rays of the sun, the pair A. Parkhomenko — N. Ivanov began to move through a complex jumble of corners, approaching the cornice-mushroom (sect. R25–R26). Under the mushroom, N. Ivanov hung control cairn #2 in a flask. It was:

- Protected from water and falls;

- Exactly in the center of the tower;

- Visible not only from the overnight stay but also through a strong tube from the moraine.

The cornice and the rocks above it were monolithic, almost without cracks. After a slab (sect. R26–R27), a characteristic crevice followed, where one could squeeze in some places, but its edges were extremely smooth; after a more gentle slab, we approached a ledge under an overhang, stretched across the tower (sect. R29–R30). Water began to flow from above.

In the A. Urodkov — N. Ivanov rope, A. Urodkov replaced N. Ivanov. He traversed less than a rope length but during this time became numb under the flow of icy water and wind. We decided via radio to stay overnight at the previous location.

Fourth day — July 9, 1980. In the morning:

- Everyone began to pack up the bivouac.

- The E. Chasov and O. Shumilov pair went light to the end of the ropes.

The ropes were frozen, but our ascenders held well on them. The clove hitch slipped, so we went with additional belay.

The rocks had dried overnight due to steepness and wind. We moved up an outer corner (sect. R24–R25). Further complexity was determined not by steepness but by the smoothness of the rocks and lack of cracks. After some time, we reached a slab where we had planned to stay overnight. At its top, there was a small notch 10–20 cm wide. Apparently, water did not reach here. Without delay, we continued further.

Behind the wall, a diagonal overhang followed; it went to the right and upwards, protecting the overnight stay and workers from ice and water. We moved under the cornice, inevitably drifting to the right where it tapered off. At 10:00, water began to flow, and by this time, the leader had exited the cornice's protection (streams flowed along its surface under it).

The weather worsened. A strong wind carried spray under the overhang where the group stood. Since the overnight stay was close, A. Parkhomenko replaced E. Chasov and completed the cornice. Further on, the next overnight stay location was visible. We decided to stop work and traverse this section in the morning, before water appeared. We did not hang all tents yet, waiting for the ice to stop melting and the water to stop flowing.

We lit a primus stove and drank:

- Tea;

- Milk;

- Soups.

In the evening, we hung tents in tandem — three in the larger one, two in the smaller one, and one in between. We leaned our backs against the cold wall, with our feet in the air on the suspension loops. Due to cloud cover, the night was warm, and our equipment did not freeze, but we slept very poorly:

- Wet legs in harnesses were numb;

- "Fifth points" slipped off the ledge;

- Belts pressed on the chest;

- Damp down jackets did not provide warmth.

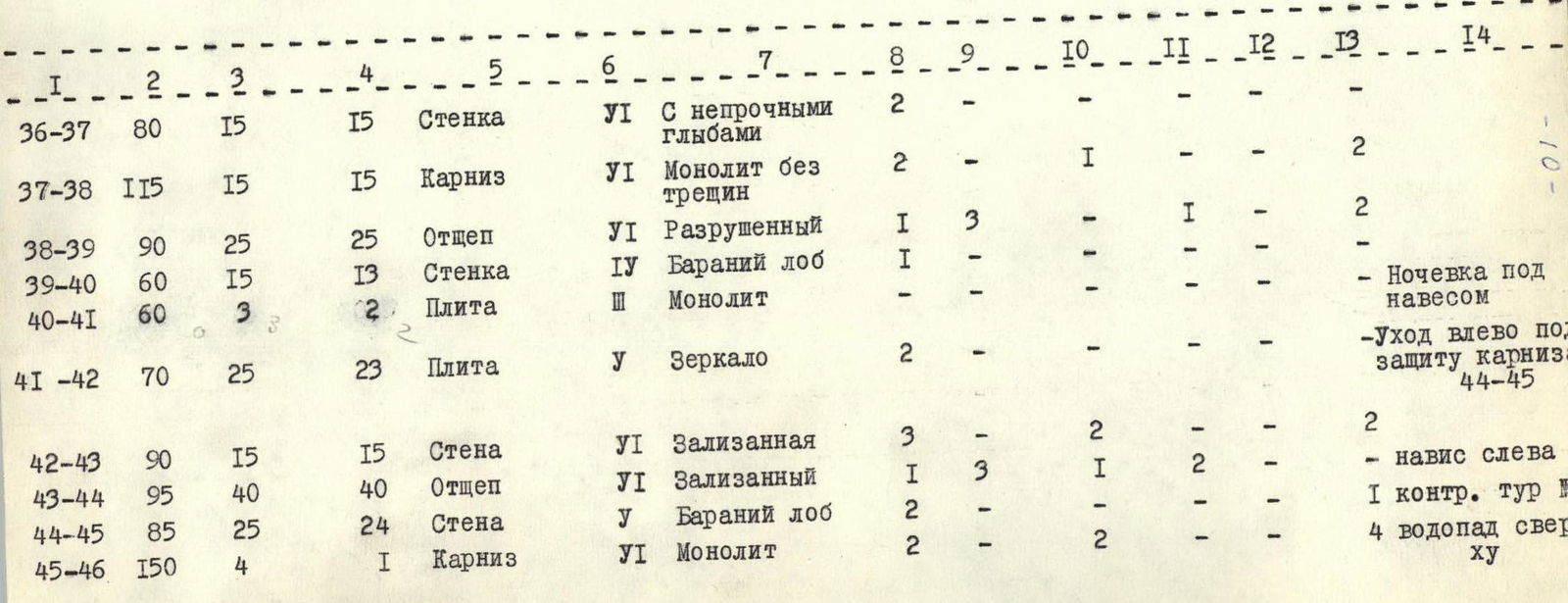

Fifth day — July 10, 1980. Eagerly awaiting dawn, I. Borodatsky and N. Ivanov went upwards. On the cornice (sect. R37–R38), we had to hammer in a piton. Above it was a reddish, destroyed slab, where we used:

- Chocks;

- A wooden wedge.

The previously considered slab was completely smooth, but under a huge overhanging wall to the right, in a depression, there was ice, making it a suitable overnight location.

We decided to bypass this wall to the left (to the right was a polished couloir with traces of ice falls and occasional icicles) in an arc:

- Left — up;

- Right — up.

This way, we remained under the cornice's protection. At the end of the wall (sect. R44–R45), under the cornice, there was an original cave, half a meter wide and deep, and 1 m high. We set up control cairn #3 there. It was visible from the overnight stay and could not be bypassed.

A. Parkhomenko went ahead and worked on the cornice. Tomorrow, we planned to reach the ice. We received "good night" wishes from observers via radio and hung in our tents. Tonight, O. Shumilov and N. Ivanov decided to sleep in hammocks. The hammocks were hung one under the other in a tent. The four of us literally hung "like sausages" in our systems.

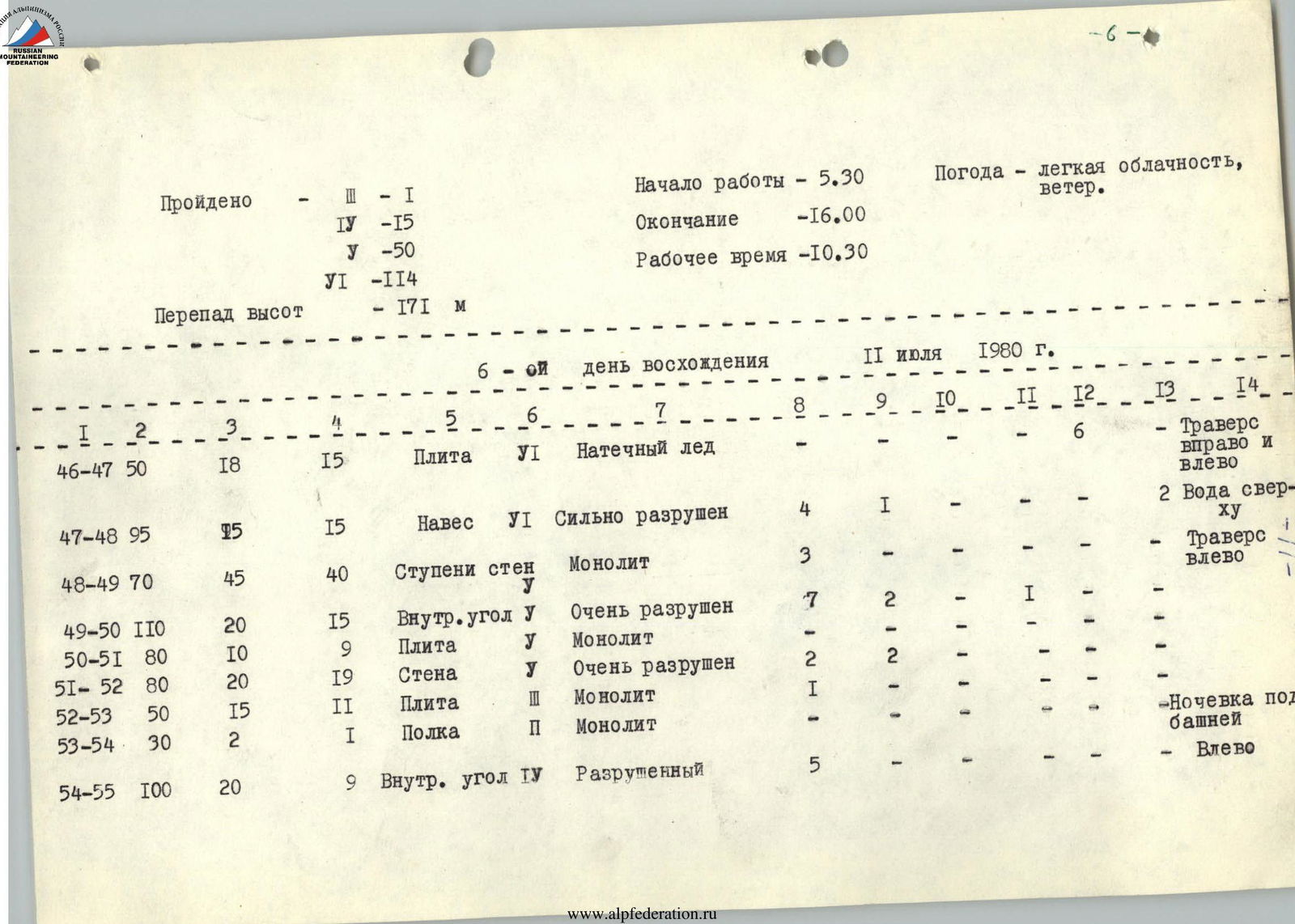

Sixth day — July 11, 1980.

In the morning, E. Chasov and O. Shumilov went up to a slab covered with ice (sect. R46–R47). The ice was permanent (winter ice) and topped with rime. At the edges, all cracks were filled with ice, but in the middle, the ice layer was insufficient for securing ice screws. Here, ice chocks helped, which were screwed into holes made with ice axes.

We traversed:

- To the right;

- Then to the left under the overhang.

At this point, a stream from above ceased (it formed the ice), but this was still the "simplest" path. We pulled up backpacks from the overnight stay to this location.

Steps on the rocks were traversed under the wall itself; the general direction was left-upwards, then we passed a very destroyed, overhanging internal corner — the last protection and the last obstacle before the ice (sect. R49–R50).

By 12:00, E. Chasov reached a slab (sect. R52–R53), from which the entire huge, sunlit ice wall of the hanging glacier was visible. The sight was amazing, unique, and intimidating.

Slightly higher:

- There was a beautiful ledge, almost a meter wide;

- Above it, a forty-meter wall served as our protection.

The entire team caught up, warmed up in the sun, and dried their clothes.

Under the wall's protection, we could ascend to its top. The path was visible a little to the left — through two internal corners (sect. R54–R56). The most unexpected thing was found at the top — a pit under an overhanging rock. We called this place "bunker." From it, like from a DOT, we could examine the entire ice wall in detail.

We have almost comfortable overnight stay, of course, seated. All team members climbed one by one into the "bunker" to examine the wall.

Before bed:

- We outlined the path on the ice;

- Brought ice equipment into the "bunker";

- Sent a request to observers via radio to order a car from the alpine camp.

The mood was elated — tomorrow was the assault!

Seventh day — July 12, 1980. Careful study of the ice ledge and preparation for the exit the previous evening allowed us to start work deep in the night. A. Urodkov and N. Ivanov worked. By dawn, when the group caught up with the "bunker," processing of the ice wall was already underway.

Above the "bunker" was a slab polished by ice. The first person traversed it in galoshes, putting on crampons at the junction with the ice; for safety, we:

- Put on crampons in the "bunker";

- Climbed on them along the ropes;

- Overcame these uninviting 15 meters.

Behind the gentle ice covering this slab above, the ice wall began (sect. R59–R60), monolithic in the lower part and destroyed in the upper (sect. R60–R61). Here, after collapse, a narrow (0.5 m) horizontal ledge formed, and above it, the ice wall overhung. Along the junction of two planes, a chimney formed (sect. R62–R64), leading to the next ledge. The ledge itself was a broken-off ice block, but all belay was set up on ice screws screwed into the monolithic main wall. Above us, this monolithic wall turned into firn. Ice screws were useless here, and crampons were ineffective.

We expected this; we had brought:

- An ice axe;

- An ice hammer.

By hammering them into the firn, N. Ivanov organized belay and hung ladders.

By 11:00, we had hung ropes leading to the upper gentle part of the glacier, and all backpacks were pulled up to the platform (and hung on the monolithic wall…). An hour later, the last A. Parkhomenko climbed up (the ascent of all participants on sect. R62–R63, R63–R64, R65–R66 was done on two ascenders; backpacks were pulled up on a block-brake) to the huge ice field.

We took a short rest, replenished our supplies — we ate:

- A can of honey;

- Red caviar;

- Dried apricots.

Leaving our backpacks, we went to the summit.

The ascent to the summit was very gentle, with occasional crevices.

Further, we reached the ridge:

- In the lower part — a huge ice triangle.

- The ice was smooth, with crevices.

- Further, there was an almost horizontal rocky-scree ridge.

Along it, by 14:00, we reached the summit. We took photos, replaced the note in the cairn, and added a container with a commemorative note — Olympic.

The descent to the backpacks followed the ascent path, then along the ice (on ropes) to the Amshuta ridge. We descended along the scree on the right side of the stream to the drainages, which were traversed on the left side of the stream, and then ascended along the scree to the northern spur of Amshuta. By evening, we descended to the tents, where we were joyfully greeted by our observers.

IV. Equipment and Its Use.

The equipment was selected according to the route and the tactical plan for its traversal. The overall list of equipment with an indication of the zone of its use on the route is given in Table 7.

We will describe samples of new equipment and features of well-known equipment, as well as some aspects of their application that may be useful for subsequent climbers.

-

Domestic rope, from the last year of production, was colored in three bright dissimilar colors and measured after coloring and drying. It was used mainly as a belay rope; imported rope (Austrian, 14 mm and 10 mm) was used as a safety rope (when working the first on a double rope and when moving a participant on taut belay ropes).

-

Titanium triangular carabiners with muffs and "irbis" carabiners were used. The latter were used as intermediate carabiners in cases where, when hanging them on pitons, they practically did not touch the wall, for example, on the outer ends of extenders.

-

Rock pitons included sets of types:

- Petal-shaped;

- Universal;

- Channel-shaped wide-flange.

Most of the universal and channel-shaped pitons were made according to drawings by E. I. Chasov. An author's certificate was obtained for the universal pitons. Leningrad Sudo верфь of the All-Union Central Council of Trade Unions planned to produce universal and channel-shaped pitons according to these drawings (made of steel) starting from 1981.

When traversing the lower, more dangerous (and gentler) part, existing camp universal pitons were used — to speed up the route, these pitons were left on the route.

-

A set of rock chocks of types "stopper" and "hex" had metal cables, so they could also be used as extenders.

-

Rock and ice hammers, ice axe, and ice hammer — according to foreign samples and authentic, produced in the modern period by leading foreign firms. Their functional capabilities corresponded to the route; for example, the ice axe and ice hammer were not suitable for cutting steps but were adapted for ascending a vertical ice wall.

-

Ice pitons consisted of 2– and 3-pronged ice screws with diameters of 18–22 mm and screw-type pitons — for self-belay and auxiliary purposes. Ice chocks are the end parts of ice screws (35–40 mm) with a 5 mm cable and an eyelet attached. An ice screw is used to drill a hole in rime ice, into which the chock is screwed. Thanks to the flexible cable, there is no moment in the chock, ensuring the strength of its fixation in ice of small thickness.

-

In wide, smooth, outwardly expanding cracks 30–60 mm wide, belay was organized on wooden wedges made by the team from archa. The wedges withstand up to three to four hammerings.

-

Ascenders used were of the cam type, made in Leningrad. An application for an author's certificate has been submitted for the design of this ascender; the team of applicants includes O. I. Shumilov and E. I. Chasov. These ascenders are suitable for ropes of almost any thickness and hold well on frozen ropes.

-

Bivouac equipment consisted of a camp "pamirka," a 2-person nylon tent, 2 hammocks, and warm clothing. On hanging overnight stays, two participants slept inside the small tent in hammocks, one above the other (see photo).

-

Communication with the base camp (observer) and between the leading group was carried out using two "Vitalka" radio stations; each participant had a red flare for emergency situations.

The group's nutrition was twice a day, with dried fruits distributed for a daytime snack. The diet included:

- Dried