The representative of the Leningrad team, before our departure on the route, remarked that the passage of the declared path does not solve the main problem of the wall — passage through the center via the hanging glacier. In our opinion, this "problem" does not exist, as during our stay in the base camp and passage of the qualifying route, the problematic route was regularly "hit" by ice and snow avalanches of varying power, but always sufficient for the "problem" to remain a problem.

One of the main characteristics of the object of ascent is the length of possible ascent routes from the Tamykul gorge. 3 km would be the minimum length of the path if it were possible to lay it through hanging glaciers from the foot of the mountain straight up to the summit. In this regard, when ascending Tamykul, athletes pass through a number of climatic zones. At the same time:

- at the bottom, during the hours when the wall is lit by the sun, the heat is suffocating;

- at the top, only down-filled equipment, windproof clothing, and continuous movement help to combat the piercing cold wind.

Such is the multifaceted nature of the mountain, making the ascent to its summit difficult but interesting.

2. Climbing Conditions in the Area

2.1. Exploration of the Area

The Tamdykul peak area is one of the least explored by climbers. This is evident from the fact that this highest peak in the Alay Range is not even mentioned in domestic mountaineering publications, nor is the adjacent massif of peak 5529 to the east. This is partly explained by the fact that:

- from the north, it takes several days of travel to see the alluring walls of these peaks;

- from the south, where the mountain can be reached in 2 days with a load and in 1 day without, these peaks do not appear as attractive to climbers, who see them from a helicopter on their way to more appealing giants of the Academy of Sciences Range.

Nevertheless, thanks to the efforts of tourists, rumors about the interesting area reached climbers. In 1973, a group of Taganrog climbers conducted a reconnaissance of the area, completing a pass hike and making several overflights of the dominant peaks by helicopter.

In 1975, two teams of athletes from Leningrad and Taganrog climbed in this area, experiencing the joy of pioneers. There is no information about other ascents in the area. The area has been visited by several groups of tourists.

2.2. Remoteness from Settlements

Peak Tamdykul is approximately 40 km northeast of the district center, Jirgatal (about 250 km from Dushanbe), where there is a dirt airfield with a helicopter base.

From here, you can drive a car (20 km) to the former kishlak Tamdykul and a dairy farm, i.e., practically to the entrance to the Ishtansaldy gorge.

Further:

- along the left orographic bank of the Ishtansaldy River to the confluence with the river, the beginning of which is given by the "Inaccessible" glacier;

- it is impossible to cross this turbulent river by wading — a rope bridge needs to be set up (about 20 m);

- then along the Ishtansaldy River, and then along the left-bank moraine of the Tamdykul glacier;

- after 1.5–2 hours — springs located at an altitude of 2700 m;

- from the springs — another 1 hour to the icefall;

- then 1.5–2 hours to a place convenient for a base camp, on the median moraine of the Tamdykul glacier;

- from the base camp to the start of the route — about 40 minutes of walking.

Considering the transportation of goods for the organization of the base camp without the use of a helicopter, it takes 2 days.

2.3. Weather Conditions

Books about the Pamir-Alay region reveal that this outskirts of the Pamir is characterized by unstable weather with sharp changes even during the daylight hours. Our expeditions confirmed this information.

In 1973, out of 16 days spent in the area:

- 7 days — precipitation;

- 2 days — overcast;

- 7 days — clear.

In 1975, out of 20 days:

- 12 days — variable cloudiness and daily precipitation.

1976 was more successful — out of 20 days spent in the area, only 8 days had either bad or unstable weather with precipitation.

Very often, the valleys are bathed in sunlight, while the peaks of Tamdykul and adjacent peaks are closed off by clouds for the entire day. In 1973, the reconnaissance group made 2 unsuccessful flights to these peaks from the district center, Jirgatal, where the sky was cloudless, while the highlands were completely shrouded in clouds. Apparently, this is explained by the fact that the powerful glaciation of the peaks towering above the Alay Range, peaks Tamdykul and 5529, contributes to local air cooling and moisture condensation in the micro-region of these mountains.

Here, windless weather is rare. In the valleys, a light breeze begins in the morning, which often turns into a stormy wind by the end of the day. Periodically, an "Afghani" wind blows in, and for several days, the air is saturated with dust, from which it is difficult to hide. Fortunately, the "Afghani" always ends with rain, which refreshes the nature.

In the highlands, continuous winds are characteristic of this area. In the gorges, the wind dies down by morning, but above 4000 m, even the walls of neighboring peaks do not protect climbers from piercing winds.

2.4. Relief Features

The area in question is interesting because, due to the large differences in altitude between the upper reaches of the gorges and the peaks of the ridge, it is difficult to choose a route that contains a limited number of elements of mountain relief, such as a purely rocky wall or an ice-snow slope from the foot to the summit. Pure rocky walls, often starting from the base of the mountain, lead here to:

- ice-snow cornices;

- icefalls;

- rocks covered with flow ice.

And somewhere near the summit, when victory seems so close, you come across a sheer wall, destroyed by winds and temperature changes, which requires you to pull yourself together again and feel fresh and strong, as at the beginning of the route.

If we talk specifically about the northeast wall of Tamdykul, then the diversity of forms of mountain relief is perhaps the main characteristic of the route. Two glaciers that need to be overcome on the way to the summit test athletes on their knowledge of all elements of ice technique, including the latest achievements in this field.

The rocky sections of the route, due to the fact that the mountain is generally composed of deeply metamorphosed schists and partly lava rocks, are problem No. 1 of the route. The black surface of crystalline schists, shining in the sun, as if lubricated with a thin layer of fat, does not easily grip with the "Vibram" type sole, not to mention the "rikon" boots, which were abandoned after testing in 1975. The most suitable were soles of the type:

- "botas";

- "makalu".

Although they are inferior to "Vibram" in terms of wear resistance.

Monolithic walls, climbing which is a pure pleasure, are not typical for Tamdykul. Even on sheer sections, a strong fragmentation of the microrelief is typical, with a tile-like structure of the rocks, which often misleads athletes who see numerous handholds from below but, upon closer inspection, have to apply all their skill to:

- not dropping easily removable blocks;

- ensuring insurance;

- using exclusively climbing techniques, where hands serve only to maintain balance,

to move forward.

The combination of wall sections with ridge sections, chimneys, cracks, so-called "psychological shelves," in a word, a full set of elements of mountain relief makes the northern wall of Tamdykul truly worthy of the technical class of ascents, as athletes here must demonstrate the full range of their preparation:

- on diverse rocks;

- on snow;

- on ice;

- on firn.

3. Reconnaissance Exits

In 1972, a team member from Leningrad, Zadorozhny A., reported that tourists had seen a 3-kilometer wall in the Alay Range. This news was initially met with humor, as we knew the altitude zones of the upper reaches of a number of glaciers in the Alay Range and the Matcha node (4000–4500 m above sea level), and for a 3-kilometer wall, the summit height would have to be about 7000 m above sea level. And since the time for discovering seven-thousanders in the USSR had passed, it was decided to check the depths of the gorges adjacent to the highest peaks of the Alay Range.

In the same year, the first reconnaissance expedition of Taganrog climbers was organized in the Tamdykul area. Its task was not to climb, but to use topographic methods to verify the available information on the heights of the peaks in the area and determine the absolute heights of the upper reaches of glaciers in the gorges adjacent to peaks Tamdykul and 5529, to calculate the height differences and lengths of possible ascent routes to these peaks.

The astonishment of the reconnaissance participants was great when, in 2 hours of walking from the kishlak Tamdykul, at an altitude of 2500 m above sea level, they saw the "tongue" of a huge glacier covered with surface moraine. There was no doubt — a deep gorge exists, and after some time, a wall was photographed, where the height difference from the foot to the summit was 2.3 km.

This expedition, equipped with modern topographic equipment, accomplished its task, resulting in several of the most logical ascent options to the peaks of Tamdykul being identified, and the estimated length of one of the routes was indeed about 3 km.

- One of the routes was indeed about 3 km long.

In 1973, the team first declared the northwest wall of Tamdykul as the second object of ascent in the USSR Championship but gave preference to the northeast wall of peak Engels. In 1975, the northwest wall of Tamdykul was declared the No. 1 object, but instead of climbing the wall, it turned out to be a "reconnaissance in force," as due to the lack of a helicopter and bad weather, the group approached the object with a significant (2 weeks) delay and hit a period of peak rockfall and avalanches. The 3 days spent on the wall (after which 1 rope was left intact) allowed for a more detailed study of:

- the structure of the mountain;

- the types of rocks;

- to develop further the methodology of ascents on walls composed of loose schistose and volcanic rocks.

It seemed to us that, despite the failure of that year, we already had enough information for the "three-kilometer" climb, and after making 2 more overflights by helicopter, we left for home to prepare for the meeting at the "highest level."

On August 6, 1976, and August 7, 1976, 2 more reconnaissance exits were made:

- the 1st — to the summit of peak 4100 m to observe individual sections of the route using a 60x telescope and to film a vertical panorama of the route;

- the 2nd — directly to the start of the route to determine the best time to exit onto the route and the condition of the glacier in the initial part of the route.

The reconnaissance was carried out by the members of the assault group.

Preliminary processing of the route and the delivery of any equipment and food were not carried out.

4. Organization and Tactical Plan of the Ascent

4.1. Organization of the Ascent

Preparation for the ascent and its organization were based on the significant experience accumulated by the club members during previous national championships as part of the Rostov Regional Committee for Physical Culture and Sports team. This experience includes passing a number of routes of 6B category difficulty, such as:

- the northern walls of Chanchakhi, Krumkol, Chatyna;

- the eastern wall of northern Uzhba;

- the western wall of southern Uzhba;

- the northern wall of peak Engels;

as well as completing ascents of 5B category difficulty, which are currently qualifying for the Master of Sports standard (southern wall of Kippicha, Eastern Ullu-Tau, Bodkhona, etc.).

Despite the fact that in 1973 the team became the champion of the country, the problem of rejuvenating the team and equipping it with the latest mountaineering techniques and modern equipment arose, as increasing the speed of passing the route, while organizing more reliable insurance, contributes to solving the problem of ensuring the safety of ascents to peaks along routes of maximum category difficulty.

By 1975, the necessary reorganization of the team was carried out without any reduction in the level of preparedness for ascents in championships compared to the 1973 team. On the contrary, the young people who joined the team quickly adopted all the new techniques in mountaineering, and the remaining "old-timers" were able to quickly adapt. As a result, the speed of passing wall ice sections by the team increased 4 times, and rocky sections — almost 2 times.

To illustrate these figures, 2 examples can be given:

- According to the report on the ascent of peak Jigit via the northern wall, in 1975, it took the team that won first place in the championship almost a whole working day to overcome 40 m of ice slope, while modern techniques for overcoming ice walls allowed passing such sections on the northeast wall of Tamdykul in 2–2.5 hours.

- In 1968, our team took 5 days to ascend the Kippicha peak, while in 1975, a young team member, V. Kolyshkin, climbed this wall in 1 day with a bit, beating a kind of "record" of French guide professionals.

The work done from 1973 to 1975, as well as its results, allowed us to conclude that the team is ready to pass routes of the highest category difficulty, with lengths exceeding 3 km, and to do so within a timeframe that allows athletes to reach the base camp via the summit before the onset of moral and physical fatigue, which begins to cause a state of indifference to what is happening, reduces the body's defenses, and makes a person unprepared for the surprises that are often encountered on the path of climbers. In mountaineering practice, there are well-known cases where even renowned climbers lacked a few hours to safely descend from the summit.

In terms of organizing the ascent and preparing for it, 1975 and the beginning of 1976 were dedicated to implementing the experience of exchange with American climbers and manufacturing special equipment, without which fast passage of routes is simply impossible. Numerous consultations with Vitaly Mikhailovich Abalakov provided enormous help in this work, whose ideas were fully reflected in the equipment of the 1976 team. More details about this will be discussed below.

Since the team had sufficient information about the Tamdykul massif as a whole and the northern wall in particular, it was decided:

- not to organize long expeditions associated with significant difficulties in organizing a base camp due to the expedition's overload;

- to conduct a short trip to the area with the sole purpose of completing the qualifying ascent;

- to abandon the use of a helicopter as the primary means of transporting goods, considering the unfortunate experience of 1975, as well as the experience of several other teams that sat in Jirgatal for weeks waiting for a helicopter.

Preparations for the ascent were planned to be conducted in the Caucasus, combining it with work on training new team members.

Considering the above, the following plan for the event was developed:

- July 12 – August 1 — conducting a training camp at the Ullu-Tau alpine camp to prepare Candidate Masters of Sports in mountaineering, with team members completing at least 2 ascents of 5B–6B category difficulty from among the qualifying routes.

- August 1 — flight of the team and rescue team to Dushanbe.

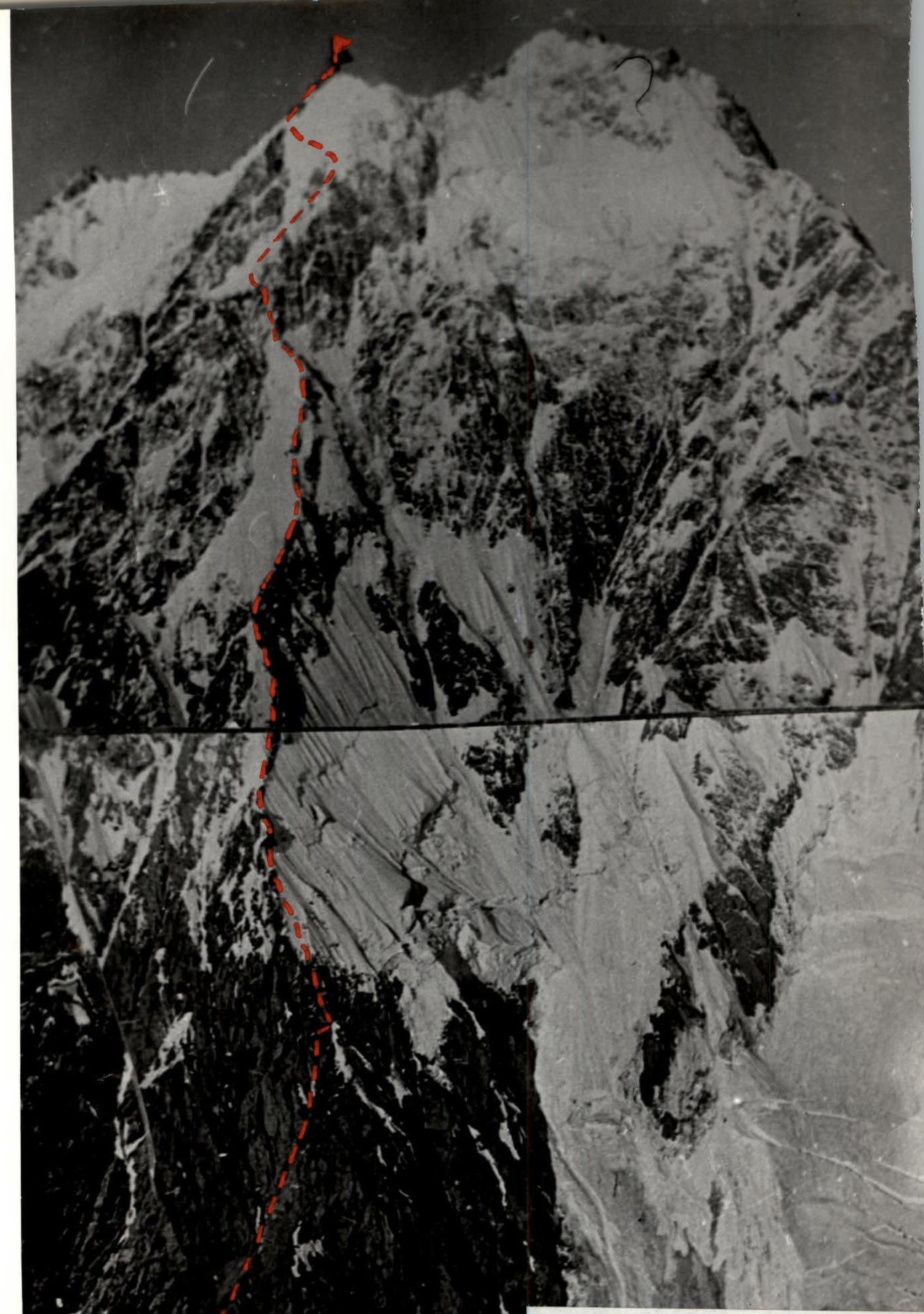

Peak Tamdykul, northeast wall. Height difference 2300 m, route length 3500 m, summit height 5450 m above sea level.

- August 3 — departure or flight of the entire expedition composition to Jirgatal.

- August 3–4 — spending time attempting to use a helicopter to transport goods and people to the base camp.

- August 5–7 — organization of the base camp and reconnaissance exits.

- August 8–17 — completing the ascent to the summit.

- August 18–25 — descent, evacuation of the base camp, reserve days, departure to Dushanbe.

The event was carried out in full accordance with this plan. At the training camp, 9 Candidate Masters of Sports were prepared, and all team members completed from 2 to 4 ascents of 5B–6B category difficulty. The speed of passing routes such as:

- Ullu-Tau-chana, Eastern via the northern wall (1.5 days to the summit);

- Dzhaylyk, qualifying route to Master of Sports (1 day);

showed the team's readiness to tackle the northeast wall of Tamdykul.

4.2. Tactics for Conducting the Ascent

As initial data for solving the tactical problem, we considered the following information and considerations:

-

The first barrier on the way to the summit is an almost kilometer-long, heavily destroyed rocky wall with an average slope of about 70° (if we exclude a wide couloir in the upper part, dividing the wall into 2 approximately equal parts). The wall includes many steeper, sometimes sheer sections, which are impossible to pass with a heavy backpack, and transporting backpacks is excluded due to the high degree of destruction and tile-like structure of the rocks.

-

Following the wall, it is necessary to pass a kilometer-long combined ridge, or rather a buttress on the wall, whose average steepness is not great — about 45°, but its passage is associated with significant difficulties due to huge ice and snow cornices covering the ridge almost along its entire length. Numerous "gendarmeries" are also crowned with caps of such cornices, resembling pillars due to their height and steepness of their walls. The accumulation of snow and ice on the tops of gendarmeries, combined with cornices, makes them resemble mushrooms, and this "nickname" has firmly stuck to them.

The presence of cornices leads to the fact that the route must be laid not along the ridge of the buttress but around it, along steep rocky and ice walls. This makes the real steepness of the route on this section much greater than the steepness of the line drawn along the tops of the gendarmeries. Transporting backpacks on this section is also highly problematic.

-

The ridge leads to the lower of the 2 glaciers that need to be overcome on the way to the summit. This part of the route is about 300 m of steep (from 60° to 90°) ice and about 100 m of less steep (from 50° to 35°) snow slope. Overcoming the lower glacier is associated with the danger of icefall and must be done at the maximum possible pace.

-

One of the most difficult tasks of the ascent is passing about 200 m of the sheer wall separating the "roof" of the lower glacier from the base of the glacier sliding from the peak's summit. The lower third of this wall is steep flow ice, reaching 90°, the upper 2 thirds — a 90-degree rocky wall composed of destroyed tile-like crystalline schists filled with flow ice. The wall is separated from the roof of the lower glacier by a large bergschrund. A safe ascent up the wall is possible only within a very narrow corridor protected from frequent icefalls by a small overhang of the upper part of the wall. The route along this "corridor" must be passed only by free climbing, as drilling this type of rock is completely ineffective. A piton after being driven causes the rock to crack and does not withstand the load.

-

The glacier sliding from the peak's summit is a unique creation of nature. Occupying a space between 2 ridges, it passes through a narrowing, due to which huge masses of ice from the left side of the glacier, sliding down, go beyond the "bed," break off, and form ice avalanches of colossal power, "overlapping" a significant part of the northern wall of the peak. On the right part of the glacier, due to the specified narrowing between the peak's wall and the sheer right bank of the glacier, a wide abyss is formed, in the depths of which icefalls constantly rumble.

Thus, the path to the summit is one — along the summit glacier, overcoming all sheer sections head-on. This is the last kilometer of the path to the summit.

-

There are places on the route for organizing, at worst, sitting bivouacs. Due to the unstable weather in the area, a tent or harnesses with individual protection from precipitation are necessary.

-

Unusually large differences in altitude and the length of the route practically exclude the use of tactics of a multi-day siege of the wall with the transportation of a large amount of goods and passing no more than 100–150 m of the path per day.

-

Passing the route using ropes for the second team to follow, as on any other route, leads to a significant loss of time, and in this case, these losses are unacceptable.

-

Transporting backpacks when passing the first 2 thirds of the route is excluded. Consequently, overloading the group inevitably leads to multiple passages of individual sections by the second team using ropes, which contradicts point 8.

Based on the above, as well as considering many other factors, the following tactics for the ascent were adopted.

- The route is passed only by independent teams, without the use of ropes, but with the use of pitons driven by the first team, when changing the leading teams during the movement, and ensuring constant interaction between the teams.

- Using the most modern equipment and high-calorie products, make the weight of the backpack for the second in the team no more than 13 kg at the start of the path, and the weight of the backpack for the first in the team — no more than 6 kg.

- Organize only joint bivouacs, as this sharply reduces the weight of bivouac equipment.

- In case of changes in weather conditions on the route, continue.

6. Observation and Radio Communication

In the expedition of the Taganrog Alpine Club, the functions of observers were performed by all other participants of the expedition, as their task was only to remain in a state of "combat readiness" and observe the route. According to the guys, there was always a queue for the 60x telescope.

The observation log, reflecting the group's movement schedule, was kept by the head of the rescue team of the expedition, Master of Sports Fedorov A.I.

To avoid cluttering the report with repeated information, we do not attach the observation log, as Fedorov A.I., present at the debriefing of the ascent, outlined the observation methodology in his speech and confirmed the team's fulfillment of the ascent schedule outlined below.

Radio communication was carried out using a radio station "Nedra" modernized at the Taganrog Radio Engineering Institute. A ten-meter collapsible mast-antenna allowed establishing stable, good radio communication with Jirgatal airport using these radio stations. A representative of the team was on duty at Jirgatal airport in case of an emergency call for a helicopter:

- daily contacted the base camp to exchange news;

- sometimes contacted the base camp several times a day.

The observation group communicated with the wall twice a day — in the morning and in the evening. In addition, the observation group listened passively every odd hour.

For emergency communication, the following were provided:

- flares;

- conditional signals for observers through the telescope.

7. Route Passage Procedure

On August 8, the group, in the aforementioned composition, left the base camp at 6:00 AM. After 1 hour, they approached the base of the route and rearranged their backpacks, as their weight was the same for everyone during the approach, and they contained the necessary equipment for working on the wall. At 8:00 AM, the weight of the backpacks was normalized, the equipment went to work, and the group started on the route. The weather was excellent, and the backpacks were not much heavier than usual, i.e., those with which we are accustomed to climbing in the Caucasus, not depriving ourselves of comfort attributes. Here, according to our observers, we "lightened up" to the point of impropriety, but this allowed us to set a high pace of passage from the first day.

We planned our working day as follows: at 6:30 or 7:00 — a very dense breakfast consisting of scrambled eggs, a piece of sausage, crackers with black caviar, sugar, and tea. At 7:30 or 8:00, we began to work. Each took with him in his anorak pocket a chocolate bar, a handful of dried fruits (mainly those containing a lot of potassium to nourish the heart muscle during work), and several pieces of sugar. This food was used at each person's discretion. Usually, everything was eaten around 1:00 PM, after which there was enough cheerful mood until the end of the work. After 10 hours of work, we set up a bivouac, and around 8:00 PM, we ate dinner combined with supper, consisting of:

- soup;

- a piece of balyk;

- garlic;

- onion;

- a sandwich with butter and caviar;

- tea;

- sugar.

Before bed, each drank 20 g of vitamin alcohol tincture of herbs, after which everyone fell asleep instantly, regardless of the bivouac conditions, for at least 3–4 hours.

When preparing for the ascent, we debated for a long time about the time to start working on the wall in the morning. In the Caucasus, we conducted a series of experiments, the results of which showed:

- starting work too early, when there is not enough light to see the relief, does not give a significant time gain;

- in some cases, an early start slows down the movement if the body has not managed to shed the previous day's tension overnight;

- then fatigue accumulates, and the athlete loses efficiency.

In our case, it was impossible to allow fatigue to accumulate, as the altitude of the stay on the wall increased daily, and with it, the complexity of the route. We had previously concluded that working more than 10 hours a day is a waste of time and effort. The impression after a longer working day is that a lot of difficult work has been done, but if you time all the work and its results, it turns out that it is better to work less but with greater productivity each day. With this in mind, we established the above-described daily schedule.

The first day spent on the wall confirmed our worst fears. We were unable to move simultaneously with 2 teams on most sections due to the high degree of destruction of the rocky rocks, and if we had not chosen the "tactics of light backpacks," we would have retreated after the first day on the wall.

The first bivouac turned out to be remarkably comfortable, if it is possible to create comfort at all by spending the night in a group of five in one tent on a small ridge, where after "construction work" a small platform like a Pamir ovring was laid out. But this bivouac was 100% safe, as we moved away from the wall by 30 m.

The second day did not bring new discoveries. We continued to move forward with great caution, testing the strength of our backpacks in relatively narrow chimneys, the walls of which strongly resembled hundredfold enlarged sandpaper. The long knife pitons, boxes, and закладные elements we made provided reliable insurance despite the strong destruction of the rocks.

Over these 2 days, in our estimation, we passed a good 5B category difficulty of rocky character. By the end of the day, we reached the ice-snow ridge and breathed a sigh of relief. Ahead was a more complex but comparatively safer path compared to the wall we had passed.

On the same day, we passed another 40 m, trying to see the further path, but the upper part of the wall still hid it from us, and we returned to a place convenient for a bivouac, leaving 1 rope as a safety rope.

Considering the "morals" of Tamdykul, we took 2 double ropes for autonomous work of the teams and 1 spare double rope on the route. We carried this rope to the very "roof" of the lower glacier, every time calling ourselves not the most intelligent people, but on the 200-meter wall, it was truly needed, as autonomous movement of the teams was not used here to ensure safety in poor weather conditions.

The next 2 days of work were spent overcoming the upper part of the wall and the ridge, or rather, a steep buttress on the wall leading to the "mushrooms." This ridge is crowned with powerful cornices and drifts. Its overcoming was a complex and fascinating task. Here, as the guys put it, we began to "score points" for the 6B category. Under us was already a kilometer-deep abyss, we walked alongside roaring avalanches, and by the end of the day, we noticed that the sky had become glassy. Someone philosophically remarked that fate, it seemed, was going to send us additional points for bad weather during the passage of the route. The prophet fell into disgrace, but it was clear to everyone that the weather was starting to deteriorate.

However, the first acquaintance with the "mushrooms" took place in good weather. Here, it is necessary to note that due to the enormous scale of the mountain, it is completely "unseen" from the base camp located near its foot. In particular, the ridge with the "mushrooms" seems completely harmless, and on the fifth day of the journey, observers from the base camp, seeing our early preparations to leave the bivouac, advised via morning communication to hurry even more to reach the rocky island under the lower glacier by noon and observe its behavior from there. We replied that we would try to reach the island by noon but could not say exactly how many days it would take. It took a day and a half of work on the most complex combined relief.

When we reached the rocky island, it was already clear to us that there was no optimal time for passing the lower icefall. By this time, we had already seen enough of it from the "mushrooms." All paths bypassing the sheer walls of this glacier were periodically blocked by large ice and snow avalanches, and we decided to go the intended way, i.e., head-on. By this time, the weather had finally deteriorated and remained so for a long time. A sharp cold snap showed that winter was arriving on Tamdykul.

The most difficult section of the route — the 200-meter wall — was passed in very poor weather conditions. Strong winds and constant precipitation did not allow developing the same speed on the wall as the group had shown on sections of similar difficulty on the ridge. It was decided, in the name of safety, to pass the wall using ropes. Due to bad weather, the group's speed decreased by almost 2 times.

In a day, we managed to pass only 120 m of rocks and reach the upper glacier. The lower 80 m of the wall were passed the day before.

The penultimate day was spent searching for a path through the glacier in thick fog under a hail of ice fragments. Although we moved almost by touch, after 2 hours, we approached a 100-meter ice wall, the overcoming of which took about 7 hours of intense work. We spent the night, having moved away from the cliff about 60 m along a steep snow-ice slope, which, however, seemed very simple after the wall.

The next morning, we were in for a surprise — the sky above us was clear, but there was still cloudiness in the area. The good weather allowed us to enjoy the beautiful panorama of the area and take a group photo on the summit using a self-timer.

On the same day, we slightly descended from the summit to a small plateau, where we stopped for a bivouac. After a few hours, we met the observers, who, having come to meet us along the descent route, completed a first ascent of the eastern ridge, approximately 5A category difficulty. In the morning, we began our descent, and the guys headed to the summit. Moving lightly, they soon caught up with us, and the further descent was carried out by separate groups but within sight.

The weather deteriorated again, and we were glad that we had given the observers permission to exit onto the route. The descent took 2 days. More detailed information about the route and individual sections is given in the previous chapters of the report and in the table of main characteristics, so in this section, we only briefly dwelled on some moments of the ascent.

9. Overall Assessment of Participants' Actions During the Ascent

Considering the complexity of the route, the large difference in altitude, and the unusually large length, it can be said that this ascent was a serious exam for all participants in all disciplines of mountaineering, which all team members passed brilliantly.

As for the technical preparation of the participants, it can be measured by the fact that more than 3.5 km of the path, including about 1.5 km of the most complex sections of the maximum category difficulty, were passed in 10 days, which is more than 2 times faster than the average speed of passing such routes by teams in the framework of the USSR Championship.

10. Data on Auxiliary Groups

All preparations for the ascent were carried out only by the group participants. The auxiliary group can include a rescue team consisting of 6 Candidate Masters of Sports, a doctor, and a radio operator, whose actions were described above.

11. Additional Data on Route Characteristics

Considering the experience of previous wall ascents, the group believes that the passed route is a 6B category difficulty route, regardless of the specific conditions of its passage. To illustrate this opinion, a comparative panorama of the passed object and routes known to the team members of 6B category difficulty is given below, as well as:

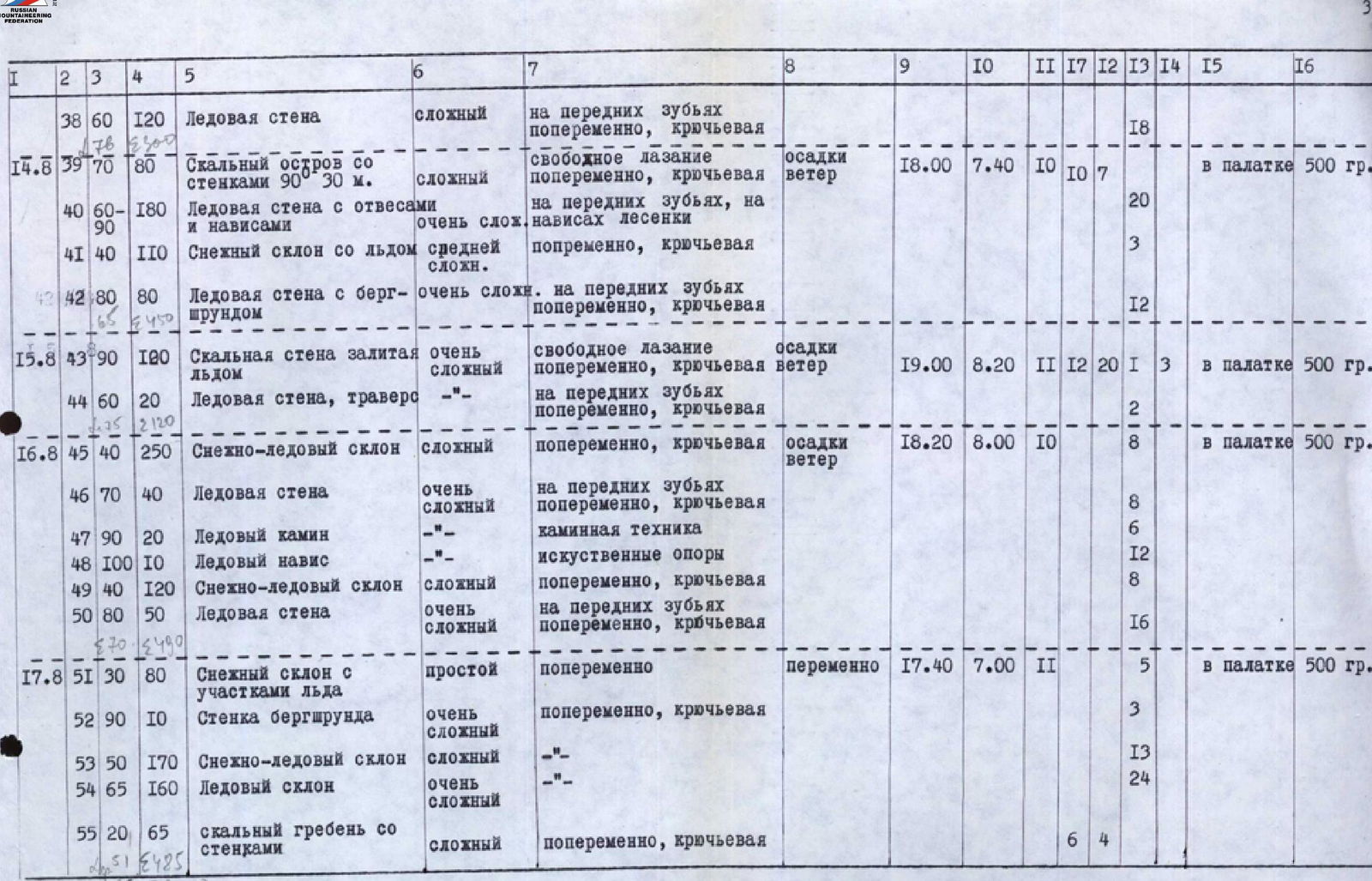

Table of Main Route Characteristics

Route of ascent to the summit of peak Tamdykul via the northeast wall. Summit height 5450 m above sea level. Height difference of the route 2300 m. Including the most complex sections 1500 m. Average steepness of the most complex rocky sections — 80° with a length of — 620 m. Average steepness of the most complex ice sections — 70–75° with a length of — 940 m. Total route length — 3500 m. Number of installed pitons: rocky — 249 pieces (including for organizing bivouacs), ice — 218 pieces, pitons — 10 pieces. Used закладные elements — 184 times. Number of working hours — 103 hours.

| Section No. | Date | Average Steepness of Section in Degrees | Section Length in Meters | Relief Character | Technical Difficulty | Passage Method and Insurance | Weather Conditions | Bivouac Time | Exit Time | Working Hours | закладных Elements | Rocky Pitons | Ice Pitons | Pitons | Bivouac Conditions | Daily Food Ration Weight |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R1 | 08.08 | 30 | 80 | Ice Slope | Medium | Simultaneously, Piton Insurance | Clear | 18:00 | 8:00 | 10 | 4 | Lying in a Tent | 500 g | |||

| R2 | 60 | 20 | Ice Slope | Difficult | Alternately, Front Points | 2 | ||||||||||

| R3 | 60 | 20 | Destroyed Rocks | Complex | Alternately, Piton Insurance, Free Climbing | 3 | ||||||||||

| R4 | 70 | 40 | Shelf on Rocky Wall | Medium | Free Climbing, Alternately, Piton Insurance | 4 | 4 | |||||||||

| R5 | 75 | 40 | Rocky Wall with Chimney | Complex | 8 | 6 | ||||||||||

| R6 | 85 | 40 | Rocky Wall | Very Complex | 8 | 4 | 2 | |||||||||

| R7 | 60 | 40 | Rocky Ridge | Complex | 5 | 3 | ||||||||||

| R8 | 40 | 70 | Scree Ridge |