Passport

- Class — winter ascents

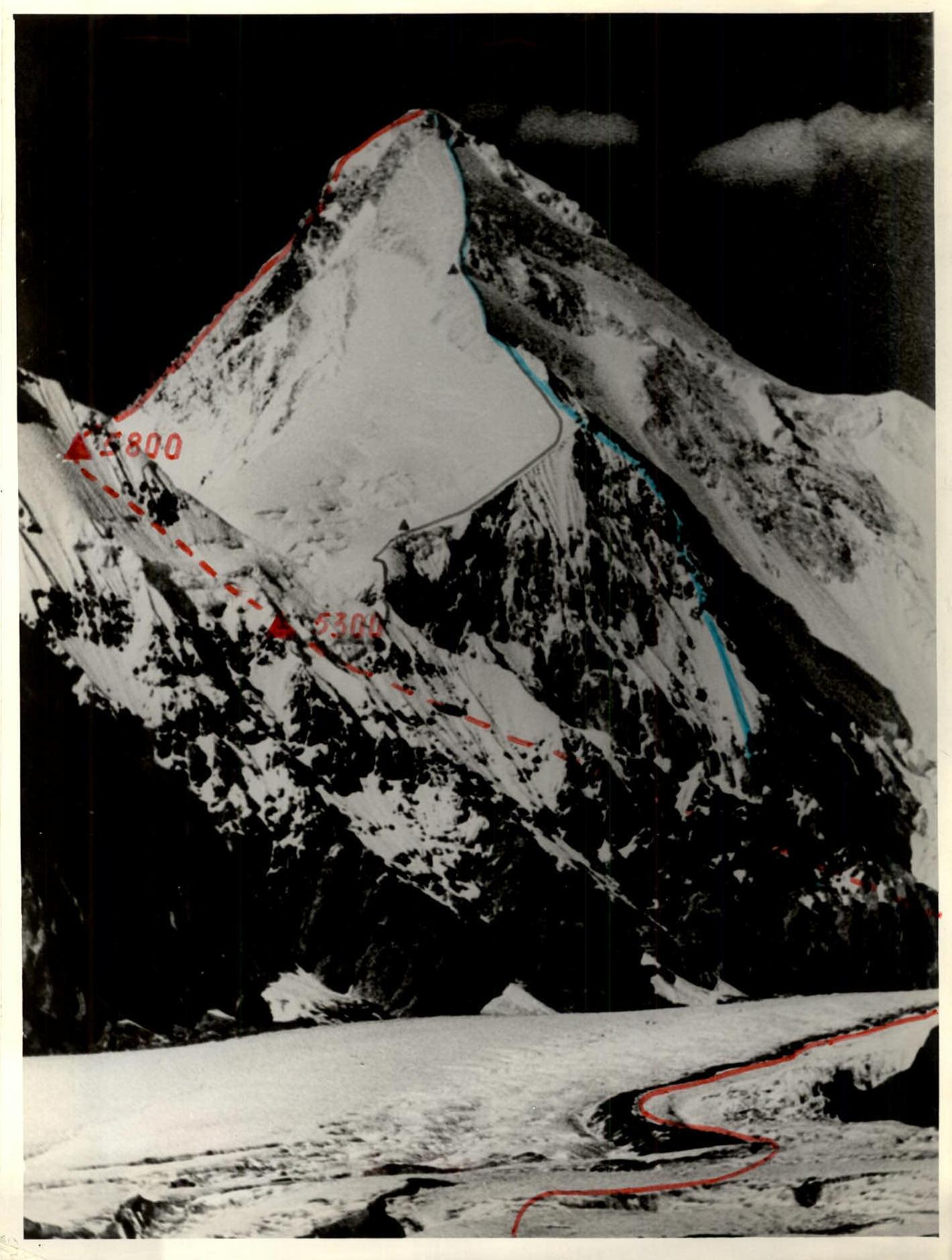

- Central Tien Shan, Tengri Tag ridge

- Peak Khan-Tengri via the southwest slope

- Proposed 6A first ascent in winter conditions

- Elevation gain: 2800 m (from the confluence of the Semenovsky and South Inylchek glaciers)

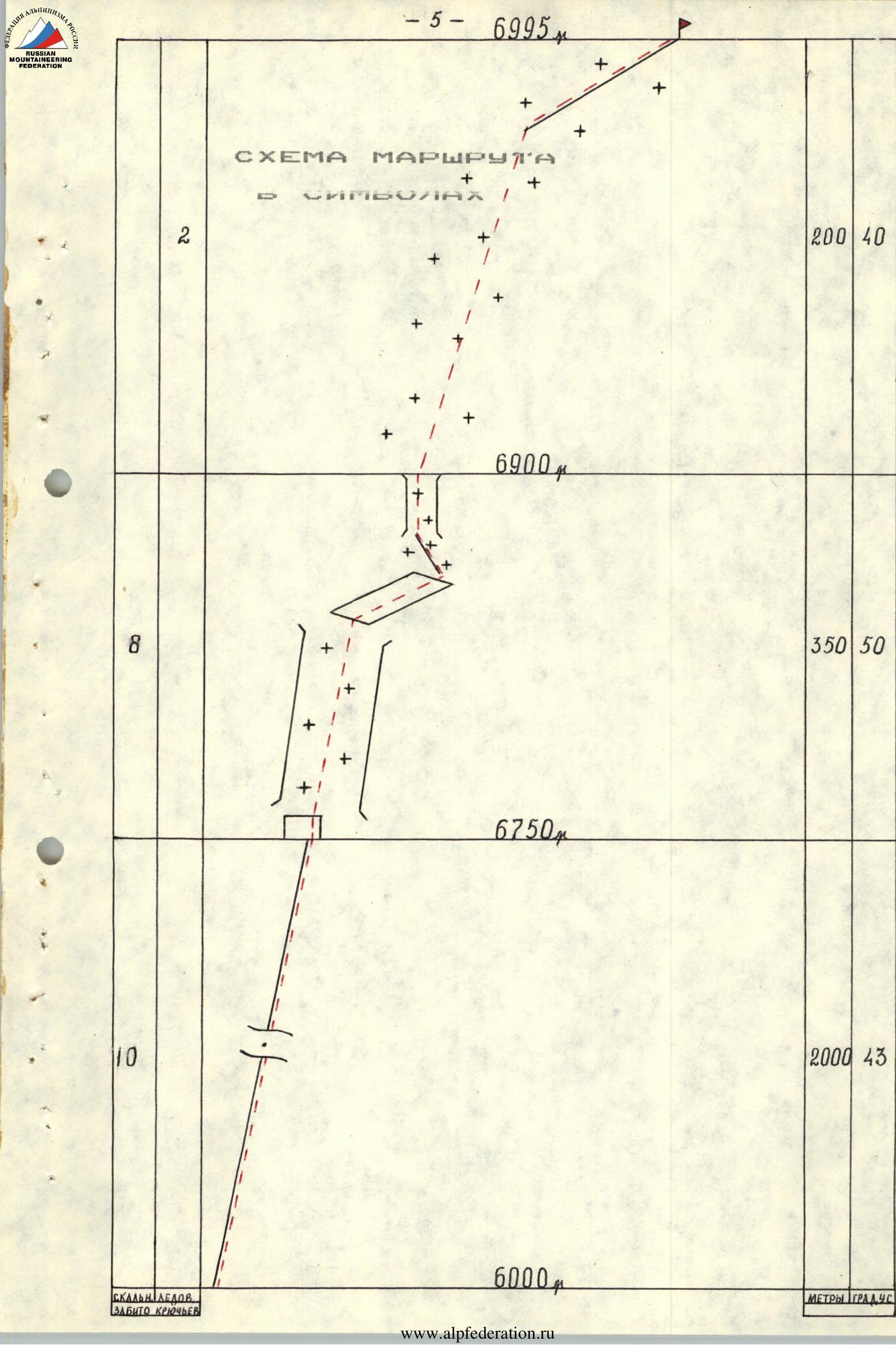

Average steepness of the main part of the route — 45° (from the saddle between peaks Chapayev and Khan-Tengri to the summit of Khan-Tengri 5800–6995 m)

- Pitons used: rock — 6 pcs., ice — 4 pcs.

Previously used pitons not removed — 12 pcs.

- Team's total climbing hours: 28 hours and 4 days

- Overnight stays: 2 in a snow-ice cave for 7 people

- Team leader: Suiga Vladimir Ivanovich, Master of Sports of International Class

Team members:

- Khrishtchaty Valery Nikolaevich, Master of Sports of International Class

- Moiseev Yuri Mikhailovich, Master of Sports of International Class

- Dediy Viktor Ulyanovich, Master of Sports of International Class

- Savin Alexander Borisovich, Master of Sports of International Class

- Ismetov Malik Makzhanovich, Candidate Master of Sports

- Putintsev Igor Yuryevich, Candidate Master of Sports

- Coach: Ilyinsky Ervand Tikhonovich — Honored Coach of the USSR, Honored Master of Sports

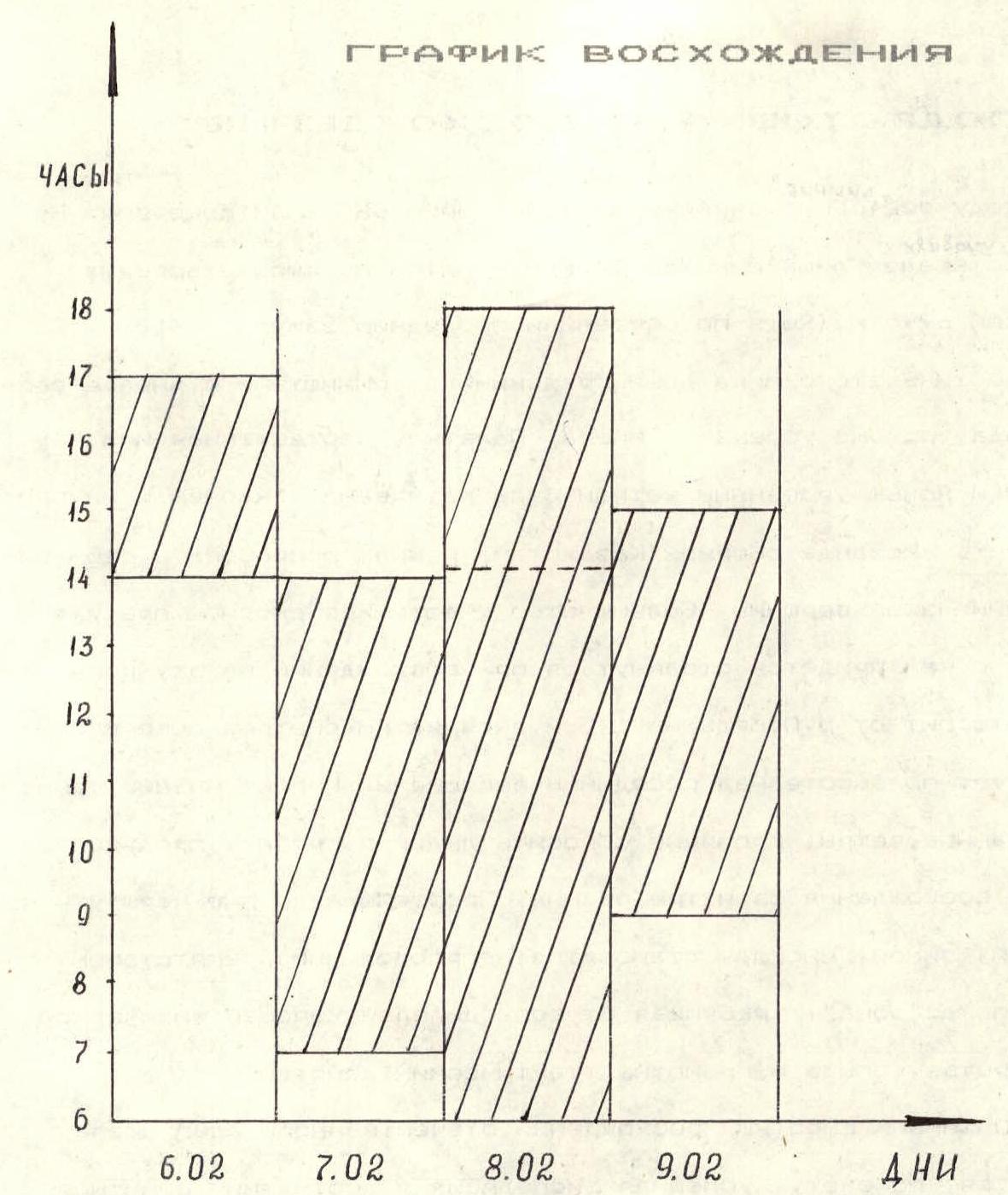

- Departure to the route: February 6, 1992

Summit: February 8, 1992. Return: February 9, 1992

- Organizing body — Ministry of Tourism of Kazakhstan

— path taken by the team via the SW slope (M-T Pogrebetskogo) — M-T Romanova — M-T Sviridenko

— path taken by the team via the SW slope (M-T Pogrebetskogo) — M-T Romanova — M-T Sviridenko

Preparation for the Ascent

By 1992, all seven-thousanders in the CIS territory had been conquered. The only unconquered peak left was Khan-Tengri — the fifth highest peak in the CIS with an elevation of 6995 m (although recent measurements indicate 7010 m). A team of Leningrad climbers attempted to reach this peak in January–February 1991 but were unsuccessful. Their tent, set up at an altitude of 6400 m, was torn apart by a hurricane-force wind at night, forcing them to retreat. The Kazakh team decided to test their skills in reaching this peak. Most team members had a good understanding of the challenges they would face during the ascent.

Khan-Tengri is located 15–20 km north of Peak Pobeda and clearly dominates the surrounding peaks in height. Extremely low temperatures, hurricane-force winds threatening to sweep people off the ridge, impose their requirements on the climbers. Simple summer routes on seven-thousanders can become insurmountable obstacles in winter.

Today, this is still a "zone" that demands from climbers:

- good physical condition,

- skill,

- experience,

- competent tactical actions.

In the history of winter high-altitude ascents in domestic mountaineering, this was the sixth successful expedition to reach seven-thousander peaks and the first on winter Khan-Tengri.

Most team members had experience in high-altitude winter ascents:

-

Suiga V.:

- In 1986, as part of the USSR national team, he made an ascent of Peak Kommunizma from the north.

- Participated in a winter ascent of Peak Pobeda in 1990, reaching an altitude of 7000 m; the ascent was not completed due to deteriorating weather conditions.

- Has ascents in the Himalayas on eight-thousanders:

- Kangchenjunga (8586 m) — twice, main summit.

- Yalung Kang (8505 m).

- Dhaulagiri (8167 m) — via the west face.

- All ascents were made without oxygen.

[11] — ascent to the main summit [7-7] — ascent to the summit of an expedition member

[11] — ascent to the main summit [7-7] — ascent to the summit of an expedition member

-

Khrishtchaty V.:

- High-altitude ascents:

- 1986 — Peak Kommunizma from the north.

- 1988 — Peak Lenin from the north.

- 1990 — Peak Pobeda from the north.

- Himalayan ascents:

- 1982 — Everest via the southwest ridge (with oxygen).

- 1989 — Kangchenjunga (8586 m, main), Yalung Kang (8505 m), Middle (8482 m) — without oxygen.

- 1991 — Dhaulagiri (8167 m) — without oxygen.

- High-altitude ascents:

-

Moiseev Yu.:

- 1986 Peak Kommunizma from the north, 1988 Peak Lenin from the north, 1990 Peak Pobeda from the north to 7000 m.

- Himalayan ascents: 1988 Dhaulagiri (8167 m) via the southwest ridge, 1989 Kangchenjunga Main (8586 m), 1991 Dhaulagiri (8167 m) via the west face.

- All ascents were made without oxygen.

-

Dediy V.:

- 1988 Peak Lenin from the north, 1990 Peak Pobeda from the north to 6000 m.

- In the Himalayas: 1989 Kangchenjunga Main (8586 m) without oxygen and Yalung-Kang (8505 m).

-

Savin A. — had no high-altitude winter ascents. But more than a dozen summer ascents, as well as an ascent via the west face of Dhaulagiri without oxygen, gave him the right to participate in the winter ascent of Khan-Tengri.

Ismetov M. — had no experience in high-altitude winter ascents. In the 1991 season, he climbed all five highest peaks in the CIS. Moreover, his ascent of Peak Pobeda from the Zvezdochka glacier to the summit and back was completed in one night, and his ascent of Khan-Tengri from the South Inylchek glacier to the summit and back was done in a single daylight period.

Putintsev I. — also made his first high-altitude winter ascent. He has several summer ascents on seven-thousanders to his credit:

- Peak Pobeda,

- Khan-Tengri,

- Peak Lenin,

- Peak Kommunizma.

Although the last three team members had no previous high-altitude winter ascents, their experience in summer ascents and selection through a rigorous competitive process at the Chimbulak gathering allowed them to take their place among the future climbers.

The regulations for the winter CIS mountaineering championship somewhat puzzled us. Apparently, when drafting the regulations, the possibility of a winter high-altitude ascent was not considered, and the team size was limited to six.

The Kazakh national team, after completing a winter ascent of Peak Pobeda in 1990, had planned to attempt a winter ascent of Khan-Tengri in 1992.

In winter 1991, the team could not travel to Central Tien Shan because the main forces were engaged in an ascent via the west face of Dhaulagiri.

While preparing over these two years, the team did not expect that the ascent would be submitted for the national championship.

The ascent was initially planned with a larger team, but to comply with the regulations, the coaching council had to limit the number of participants to eight.

To ensure the safety of a high-altitude ascent in challenging weather conditions, a larger number of climbers is required. This is confirmed by the team's own experience in winter ascents:

- In 1974, during an attempt to ascend Peak Lenin, the participants managed to survive only because there were 10 people in the group, and they were able to bring down two team members who had lost the ability to move on their own in strong weather conditions.

- From the experience of the USSR national team in 1986 on Peak Kommunizma: a rescue team of six worked on the slope at night, while four were positioned on the slope to ensure the safe return of the rescuers to the cave.

- Something similar occurred on Peak Lenin in winter 1988 and on Peak Pobeda in 1990.

Having gained experience in high-altitude winter ascents, the Kazakh team planned to allow eight participants to ascend Khan-Tengri, but the acclimatization sortie made adjustments — one participant fell ill, and the team doctor did not recommend him to participate in the ascent.

Team members trained year-round. Utilizing the unique conditions of Almaty (proximity to mountains and climbing routes), they made ascents on weekends. Before the expedition, they conducted a ten-day training camp at Chimbulak, where participants made 4–5 ascents.

Since, based on tactical considerations and the experience of the Leningrad expedition in 1991 (see "Tactical Actions of the Team"), it was assumed that the southwest ridge of Khan-Tengri would be traversed as many people as possible would be able to safely descend from the summit to the acclimatization point at 5800 m and back, it was proposed that participants at the Chimbulak gathering daily gain up to 2.5 km of elevation:

- 1.5 km in the morning (typically an ascent to the summit of Amangeldy);

- up to 1 km in the afternoon (either several ascents on a measured trail or a walk to Mynzhilki).

Team doctor A. Borisov conducted daily observations of the athletes, preventing overexertion.

Short-range radio communication between the team and the base camp was maintained using VHF "Kaktus" radios. Communication times:

- 8:45

- 13:45

- 16:45

- 18:45

Long-range radio communication between the base camp and Almaty was maintained using an HF radio. Communication times:

- 9:00

- 14:00

- 17:00

- 20:00

Tactical Actions of the Team

Based on their experience and that of other winter ascents, the team identified the main challenges they might face on the slopes of Khan-Tengri:

- Severe cold

- Hurricane-force winds

- Short daylight hours

- Highly undesirable organization of overnight stays above 6000 m

- Rapid traversal of the southwest ridge of Khan-Tengri from 5800 m to the summit and back

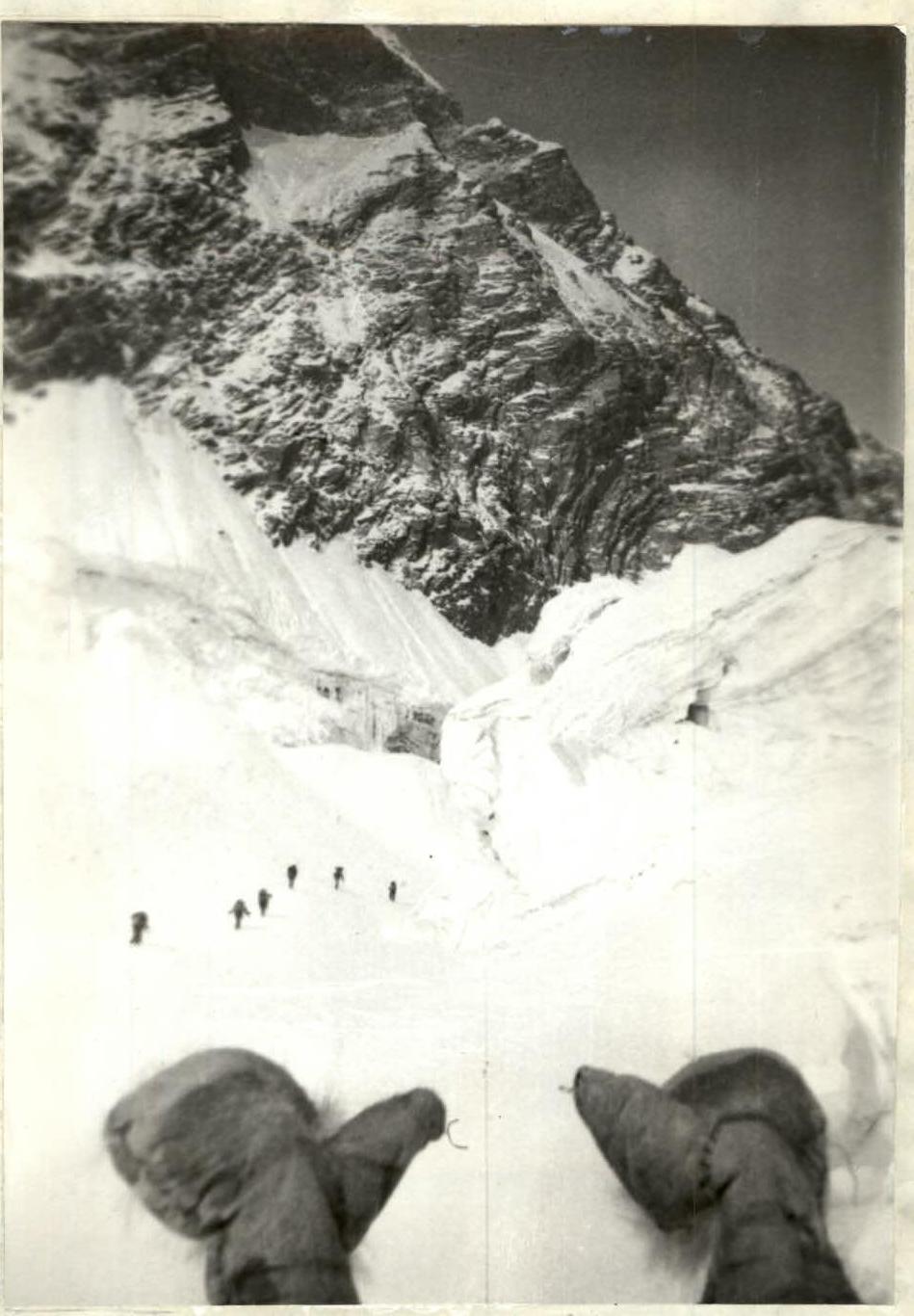

Most team members, having made an ascent of Peak Pobeda in winter 1990, fully understood these challenges. Unlike Peak Pobeda, where climbers are shielded from the direct impact of southwesterly winds by the massif of the peak, the enormous pyramid of Khan-Tengri is completely exposed from an altitude of 6100 m, and its southwest ridge "meets" all air masses head-on. Hurricane-force winds sweep snow off the ridge, "licking" the ice to a shine.

Digging a snow cave above 6000 m is impossible. Setting up a tent for an overnight stay above this altitude in unpredictable weather conditions is tantamount to defeat. The consequences of such a night could be unpredictable.

To solve the problem of a winter ascent of Khan-Tengri, the team could only rely on the fastest possible ascent, i.e., within a daylight period:

- from the 5800 m saddle (where a cave was dug)

- to the summit

- and back to the 5800 m saddle.

In summer, with good acclimatization, such an ascent is not a problem.

The team, using their knowledge of the area, experience from previous high-altitude winter ascents, and the experience of the unsuccessful winter attempt on Khan-Tengri by the Leningrad team in 1991, developed a tactical plan for the summit, dividing it into two stages:

- acclimatization

- summit assault

Acclimatization

Day 1. Departure to the confluence of the South Inylchek and Semenovsky glaciers (4200 m).

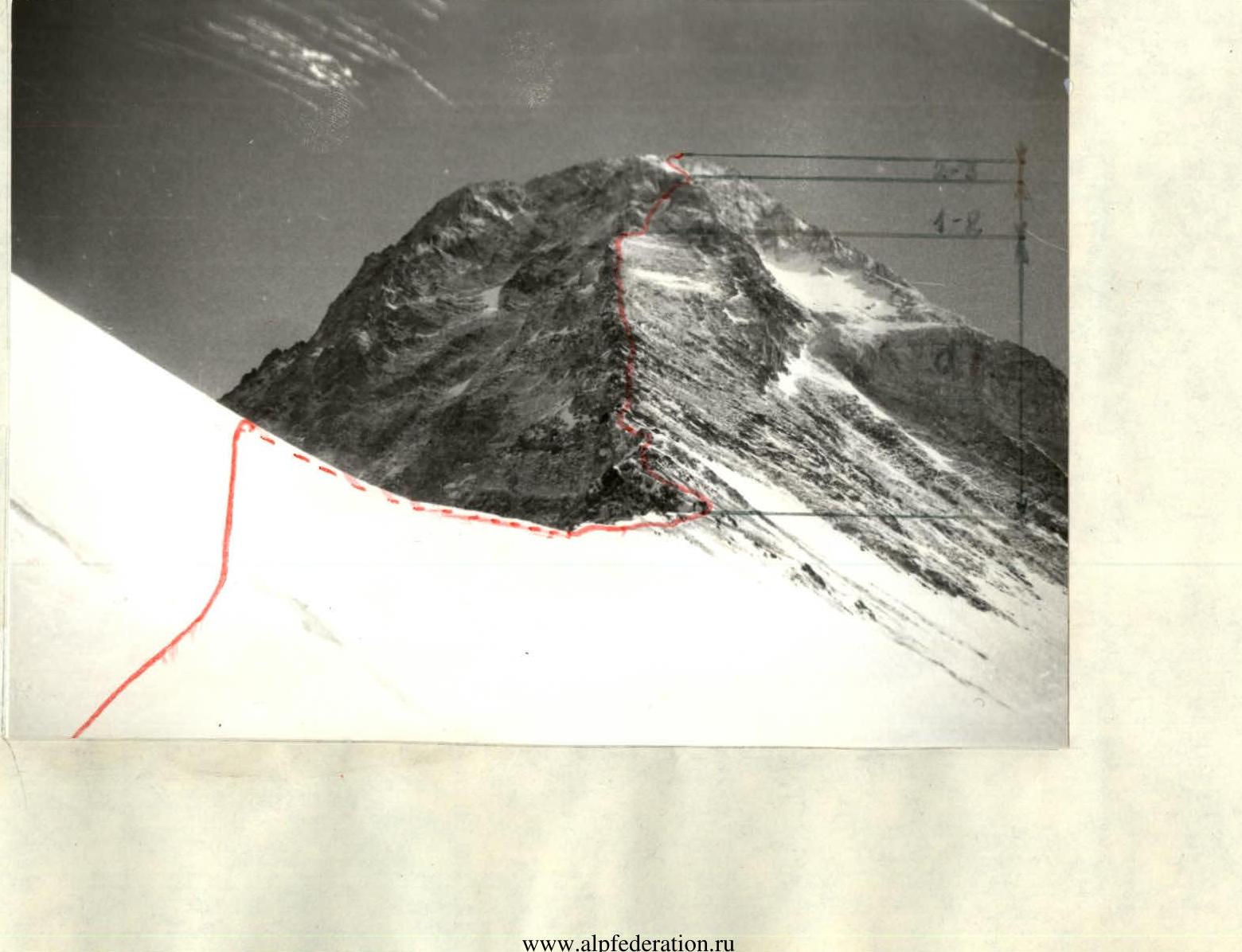

Day 2. Ascent to an altitude of 5200–5300 m and establishment of a camp in the fractures and crevices of the Semenovsky glacier. Possibly even digging a snow cave there.

Day 3. Ascent to the saddle between Khan-Tengri and Chapayev to an altitude of 5800 m and, without reaching the saddle itself, digging a snow cave. It may not be possible to dig a cave on the saddle due to the lack of snow (due to strong winds).

If time permits, take a walk up the southwest ridge, at least to an altitude of 6000 m.

Day 4. Early morning departure up the southwest ridge as high as possible and return to the confluence of the South Inylchek and Semenovsky glaciers on the same day. If snow conditions are favorable and weather is at least satisfactory, it may be possible to return to the base camp.

Day 5. Return to the base camp. Days 6 and 7. Full rest days in a heated tent at the base camp, enhanced nutrition.

Summit Assault Stage

Day 8. In the afternoon, departure to the confluence of the South Inylchek and Semenovsky glaciers (4200 m).

Day 9. Early departure and transition to the cave at 5800 m under the saddle.

Day 10. Decisive day for the assault. Considering the short daylight hours, early departure. Traversing the southwest ridge to the summit and back to the 5800 m saddle.

Day 11. Return to the base camp.

Day 12. Reserve day for bad weather.

On January 31, the team began the first stage — acclimatization. In the middle of the day, they left the base camp, located on the glacier between the Zvezdochka and South Inylchek glaciers, towards the Semenovsky glacier. After 5 hours of work through deep snow, they spent the night in tents on the confluence of the South Inylchek and Semenovsky glaciers.

February 1. In the tents — a thick layer of fluffy snow condensate on the ceiling, walls, and belongings. Despite this, they departed at 8:00. By lunchtime, they reached an altitude of 5300 m. A broken icefall blocked their path. Only by evening did they manage to find a passage. After lunch, a powerful icefall collapsed from the slopes of Peak Chapayev. It overflowed the Semenovsky glacier five hundred meters below their icefall and came to a stop against the slope of Khan-Tengri.

February 2. Very cold. The condensate from breathing had accumulated even more in the tents than the day before. The wind direction within the gorges often differs from the general westerly direction. Today, it blows in their faces from the direction of the saddle.

In some places:

- extended deep snowdrifts,

- wind-smoothed dense firn and ice.

Often — wide open crevasses. When traversing the icefall, they hung two ropes. An hour after the afternoon radio check, they approached the saddle and dug a cave.

On the same day, they traversed the southwest ridge of Khan-Tengri to an altitude of approximately 6100 m. The entire day was marked by haze, cold, but a moderate westerly wind. The southwest ridge was completely cleared of snow by the wind.

On the morning of February 3, the weather improved slightly, but it became colder. They ascended again to an altitude of 6100 m and headed down to the base camp to avoid the icefall danger zone before lunch. Their tracks were covered, and even when crossing the South Inylchek glacier, they had to re-tread them. They arrived at the base camp by 17:00.

Two and a half days of rest in a double, heater-warmed tent at the base camp restored their strength. On February 6, the team began the second stage of their tactical plan. After lunch, seven participants in the assault departed towards the confluence of the South Inylchek and Semenovsky glaciers (4200 m). The fact that they now took about three hours to cover the same distance that took 5 hours on their first sortie indicated their gained acclimatization and instilled hope for success.

On February 7, they departed at 7:00. Very cold. Sharp gusts of wind occasionally blew from the direction of the saddle. Limbs were slightly frostbitten, and they had to flap their legs to restore blood circulation. They quickly ascended using the fixed ropes in the icefall and gathered in the cave under the saddle at an altitude of 5800 m by 14:00.

On February 8, they departed at 6:00. For over an hour, the team worked with headlamps on. It was very cold on the saddle. Rucksacks were maximally lightened, containing:

- a primus stove with fuel

- a half-liter can with fuel

- a tent

- two hammers

- 10 rock and 5 ice pitons

- minimal reserve supplies

Two 45-meter ropes were used in the teams. Each carried about 2.5 kg of shared gear.

From an altitude of 6300 m, the wind strengthened. Some ropes left by international alpine camps were blown over the ridge by the wind. They didn't have time to retrieve them. The remaining ropes on the route were heavily worn and frayed by the powerful winds against the rocks. They could only be used for support. As they gained altitude, the wind grew stronger, the cold more biting, and movements became more labored.

On the southwest ridge, at an altitude of 6700 m, before the diagonal traverse into a wide couloir, lies the body of V. Pyatiletov — a member of a tourist group from Petropavlovsk-Kazakhstan. He died in August 1991 during descent from the summit.

The pre-summit ascent was on very dense, almost ice-like firn.

Around 14:00, the entire team reached the summit. The camera, kept under a jacket and scarf in a chest pocket, froze, and after the first shot on the summit, the battery died.

The hurricane-force, gusty westerly wind did not allow them to:

- linger on the summit;

- fully record all those who reached the summit in the note.

The radio station's batteries were frozen, and in a brief message, they managed to transmit that the team was on the summit, everyone was fine, and they were starting their descent.

As they descended from the summit, the team was out of the direct wind impact. However, while ascending, the westerly wind blew mainly from behind, and only its oblique, reflected streams hit their faces. During the descent, they faced it head-on.

Ice-cold streams:

- seeped under the hoods of their down jackets,

- penetrated woolen, canvas, and neoprene gloves,

- especially affected their faces despite masks.

On the slopes, the wind somewhat subsided, but powerful gusts still threatened to sweep the teams off the ridge. As they descended into the gathering dusk to the cave, many team members' faces showed signs of frostbite.

On the descent, passing by Pyatiletov's body, they attempted to lift it onto a nearby ledge and somewhat cover it, but the corpse was frozen to the rocks, and their attempts to dislodge it were unsuccessful.

The short daylight hours did not allow them to linger near the body, and they were forced to continue their descent after futile attempts to detach it from the rocks.

The next day, February 9, the team arrived at the base camp in the afternoon, and on February 10, they arrived at the Burunday airport in Almaty by evening.

Table of food and fuel supplies

| 1. Lard | 1.0 kg |

| 2. Sugar | 2.0 kg |

| 3. Tea | 0.2 kg |

| 4. Crackers | 2.0 kg |

| 5. Salt | 0.2 kg |

| 6. Fresh meat | 0.7 kg |

| 7. Fresh chicken | 1.0 kg |

| 8. Dehydrated products | 0.6 kg |

| 9. Butter | 0.5 kg |

| 10. Nuts | 0.7 kg |

| 11. High-calorie mix | 0.7 kg |

| 12. Rice | 0.7 kg |

| 13. Buckwheat | 0.5 kg |

| Total: | 10.8 kg |

Route Description by Sections

Section R0–R1. Rocky ridge. Movement proceeds slightly to the right on the slope. Uncomplicated rock climbing. Often in couloirs, on inclined ledges, dense firn or ice. The upper part of the diagonal traverse from left to right upwards to a large couloir, traverse across slabs. On the slabs — ice and dense firn, lightly dusted with snow.

Upper part of the diagonal traverse from left to right upwards to a large couloir:

- Traverse across slabs;

- On the slabs — ice and dense firn, lightly dusted with snow.

Section R1–R2. Wide, trough-like couloir. In the lower part — a 8–10 m rock wall. On the rocks — dense firn and snow. In the couloir — dense firn. In its upper third — snow up to 40 cm deep, lying on dense firn.

From the couloir:

- traverse right upwards onto a snow-ice ridge

- then a 40–50 m rock section.

Section R2–R3. Steep ice-firn slope leading to an ice ridge that continues to the summit.

Due to the lack of a general photograph of the Semenovsky glacier, two more technically interesting sections cannot be clearly illustrated:

- In the upper part of the icefall fractures at an altitude of around 5300 m, when traversing the ice breaks on the glacier, they had to hang two ropes on steep — up to 50° — ice sections.

- When reaching the saddle (5800 m) from the bergschrund, there was a 40–50° ice section 40 m long.

Technical Photographs of the Route

Photo 1. Crossing under the icefall (5200 m)