CHAMPIONSHIP OF THE USSR IN ALPINISM 1973

Class of high-altitude and technical ascents

PEAK TAJIKISTAN 6565 via the SOUTHEAST FACE

The route was traversed by the team from LENINGRAD SPORTS COMMITTEE:

- Captain MS LOGACHEV Y.A.

- Senior coach MSMSK ZHITENEV F.N.

Southwest Pamir

- 1973

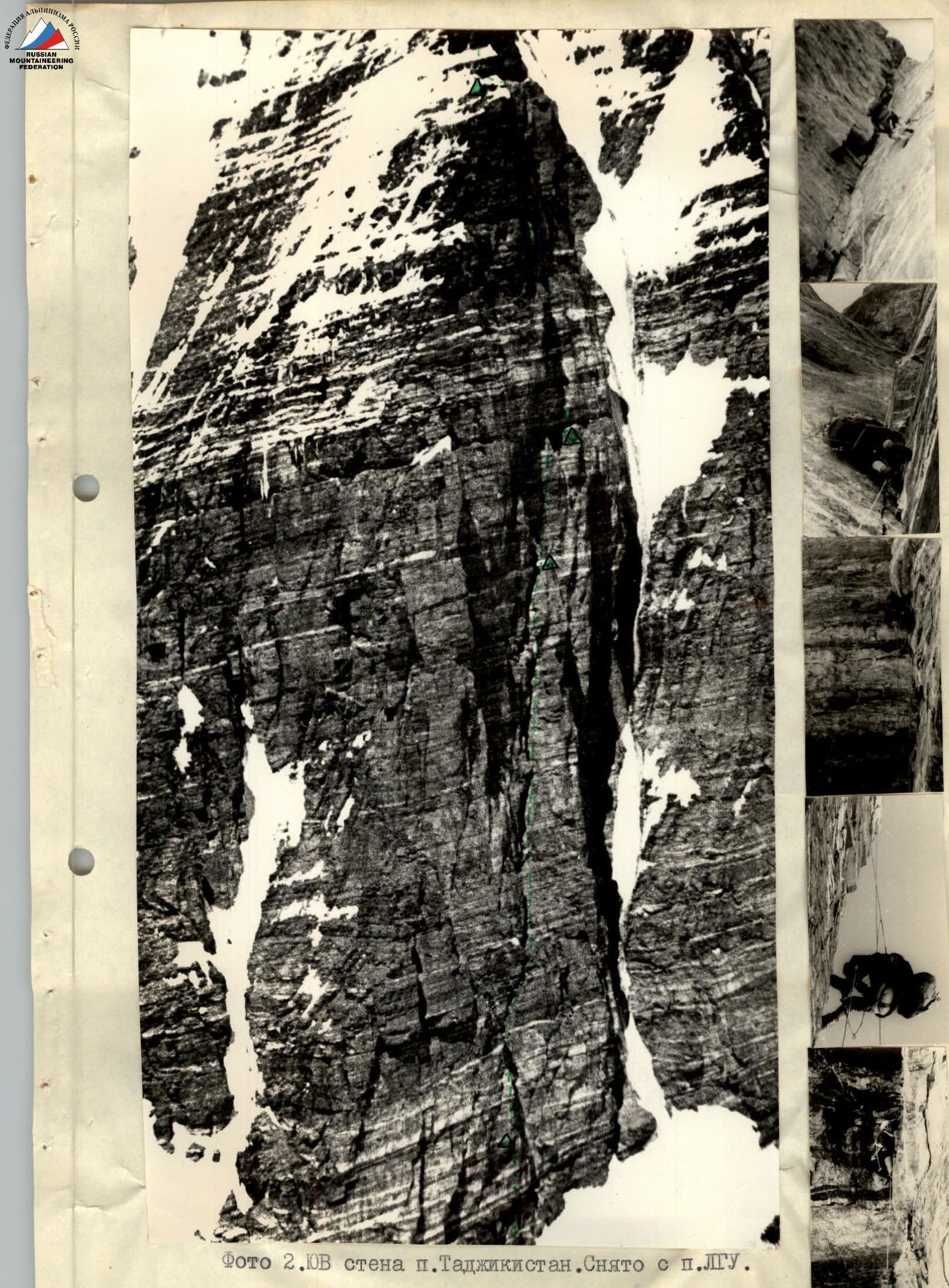

Photo 2. Southeast face of Peak Tajikistan. Taken from Peak LGU.

Brief geographical description. Sports characteristics of the region. Climbing conditions in the area.

It would not be an exaggeration to say that the fate of the USSR Alpine Championship in the high-altitude and technical class for the last 11 years has been decided in the Southwest Pamir. Only in 1965, 1967, and 1969 did climbers not bring back medals from this region. Starting from 1970, the number of climbers undertaking ascents in the Southwest Pamir has not been less than a hundred, sometimes approaching three hundred. And this is one of the most remote mountain regions from the centers of alpinism development in the USSR. Such wide popularity is ensured by:

- relatively easy accessibility,

- stable good weather,

- excellent sports reputation.

The Southwest Pamir is located on the territory of the Gorno-Badakhshan Autonomous Oblast (GBAO) of the Tajik SSR, in its southwestern corner. To the south and west, it is bounded by the border river Panj. On the Afghan side rise the seven-thousanders of the Hindu Kush. The Southwest Pamir is composed of latitudinally oriented ridges - Rushan, Shugnan, and Shakhdarin - and the meridional Ishkashim ridge, which limits this mountain country to the west. However, alpinists are particularly interested in the area of significant uplift in the Shakhdarin ridge - here, towering over the Panj valley by more than 3.5 kilometers, dominate:

- Peak Marx (6726 m),

- Peak Engels (6510 m),

- Peak Tajikistan (6565 m) - in the southern spur from Peak Marx.

The mountain rocks here are mostly metamorphic, often of sedimentary origin:

- schists,

- gneisses,

- marble.

Sometimes, non-metamorphosed rocks can be found - such as gypsum.

Map-scheme of the Peak Tajikistan area

sandstone. Layers of sedimentary rocks are often disrupted by magmatic intrusions. The layers usually slope to the north, but this gentle slope is often interrupted by faults and intense folding. For example, a giant fault has formed the almost vertical northern face of Peak Marx. The mountain rocks at the peaks are weakly weathered, and the cliffs are strong.

The Southwest Pamir is remote from the seas and is reliably shielded by powerful mountain systems on all sides. The climate here is dry, sharply continental. The annual precipitation of 150-200 mm falls mainly during the cold season and in spring. The mountain slopes are treeless, scorched by the sun. The weather is stable and clear in summer. Periods of bad weather are rare and short-lived, and the precipitation during this time is insignificant. Strong winds are common at high altitudes. The snow line is at an altitude of about 5200 m above sea level.

Despite the dry climate, glaciation is highly developed in the region:

- Glaciers like Kishty-Dzherob and Zugvand reach lengths of 12-14 km.

- The peaks of Tajikistan and K. Marx are crowned with powerful ice caps.

- A large hanging glacier lies on the summit of Peak Engels.

Alpinists typically arrive in the Southwest Pamir from Osh. After two days on the Osh-Khorog road, at the 537 km mark, the car turns south. Crossing the Shakhdarin ridge via the Khargush pass, the road continues along the Pamir and Panj river valleys through a chain of kishlaks. Another 2.5 hours, and finally, the border outpost of Langar, kishlak Isor, is reached. From here, up the Kishty-Dzherob valley - to the foot of the southern face of Peak Engels. From the camp in Kishty-Dzherob, almost the entire southern half of the region is accessible.

To reach the most western valleys:

- Dridzh,

- Nishgar,

one needs to drive about 20 km further by car to kishlak Dridzh. From here, it takes 2 days to reach the upper reaches of the Western Dridzh glacier. Here, in a hard-to-reach and infrequently visited corner, the sheer bastions of the southeast face of Peak Tajikistan hide. This face represents the slopes of the southwestern ridge. The southeastern ridge, on the other hand, is easily accessible from the Dridzh valley and represents the simplest path to the summit.

Geographic exploration of the region began in 1883 by the exiled geographer D. Ivanov and botanist A. Regel. Already on the map of 1901, the main ridges and 2 peaks in the Shakhdarin ridge are correctly marked: Peak Tsarya-Mirotvorca and Peak Imperatritsy Marii.

A significant contribution to the study of the Southwest Pamir was made by the work of the Soviet geographer S. Klunnikov in the 1930s. He also gave new names to the highest peaks in the region: Peak Marx and Peak Engels. Alpinists first appeared in the Southwest Pamir in 1946: a team led by E. Abalakov and E. Beletsky ascended Peak Marx via the western ridge.

The conquest of the three main peaks opened the way for sports ascents. By 1973, at least seven challenging routes had been traversed on Peak Engels alone, each bringing medals to its conquerors.

The northeastern face of Peak Tajikistan, visible from everywhere, also did not remain without attention. In 1966, it was traversed by a team from the Kabardinian Physical Culture Committee led by I. Kakhiani. A year later, this face was traversed through the center by alpinists from Leningrad's "Trud" (led by Chunovkin). It took them eight days to complete this route, which led to the ridge to the right of the summit. In 1971, a team from the Central Sports Club "Burevestnik" led by Bozhukov ascended via a variant of Chunovkin's route (diverging to the left in the upper part).

Since 1971, the "Vysochnik" alpine camp has been operating in the region. Dozens of young alpinists have gained access to the peaks of the Southwest Pamir. However, this did not reduce the intensity of the sports struggle; in the current year, 1973, the USSR championship in the high-altitude and technical class was almost entirely played out in the Southwest Pamir.

Four teams declared routes via the northeastern face of Peak Tajikistan. Our team also decided to familiarize itself with the face: four of its members, comprising the reserve team, and two young alpinists who had just fulfilled the standards for candidates for Master of Sports of the USSR, under the leadership of V. Lurie, traversed Bozhukov's route with three bivouacs.

Our team was not a novice here. In 1969, the most challenging ascent of the season in the Southwest Pamir was the ascent of Peak Engels via the northeastern face (Kustovsky's path). It was accomplished by alpinists from LOS "Burevestnik" led by F. Zhitenev. The following year, we managed to achieve great success - for the first time participating in the USSR Championship, the team received gold awards for traversing the northern face of Peak Marx, which many experienced alpinists at the time considered impassable.

For participation in the 1973 USSR Championship in the Southwest Pamir, where a gathering of young athletes from LOS "Burevestnik" was taking place, we wanted to choose a technically complex object with some novelty for this, seemingly thoroughly studied, region. S. M. Savvon helped us by telling about the southeast face of Peak Tajikistan and showing many photographs, one of which was published in the "Yearbook of Soviet Alpinism" for 1961-1964.

The face is a series of fairly narrow bastions separated by ice gullies. Not a single route had been traversed on this face until the current year (on the continuation of this face to the South summit of Peak Tajikistan (6300 m), routes were traversed by Donetsk alpinists in 1972). Such an object suited us perfectly, and we began preparing for the ascent.

Team preparation for the ascent

Preparation for the ascent of Peak Tajikistan essentially began in the fall of 1972, with the start of the team's training under the guidance of senior coach F. N. Zhitenev.

On one hand, in preparation for work at high altitudes, the team focused on endurance training:

- cross-country runs,

- long-distance ski races (30-50 km).

On the other hand, an essential part of the preparation was improving individual climbing technique with lower belay. Such training was conducted regularly on the rocks of the Karelian Isthmus, and in April 1973, a gathering was held in Crimea (Laspi). Over 10 days, participants trained on well-known routes popular among rock climbers and also made several first ascents (in pairs) on the western part of the Kastropol wall.

During the summer season of 1973, before the ascent of Peak Tajikistan, the team's work was planned so that each participant would complete at least one technically complex ascent not lower than category 5B before starting the route. Particular attention was paid to the style of passage - minimal use of artificial holds (hereafter referred to as "Aids"), bolt hooks, and passage of the most challenging sections by free climbing at a good pace.

Training routes for the team included:

- Salonnikov's route on Chapdara (6B category), which was completed with four bivouacs (the first ascent team had nine bivouacs),

- Petrov's route on the eastern part of the NW face of Chapdara (5B category), completed with two bivouacs,

- Chunovkin's route on the South summit of Peak Moskovskaya Pravda (5B category), completed with two bivouacs (the first ascent team had four bivouacs on the route).

When traversing these routes, the tactic of working in independent pairs was applied whenever possible, allowing everyone to maximize their time for practicing lower belay.

The composition of the assault group (eight people) was determined based on health status and the results of these ascents. All members of the assault group, except for Troshchinenko, had significant experience in wall climbing of 6B category, which allowed the team to develop a certain style of traversing technically complex sections. By the time they started the route, all team members had experience climbing peaks above 6500 m:

- Peak Marx,

- Peak Engels,

- Peak Khan-Tengri.

Preparation for the ascent also included:

- purchasing food supplies at VNIIKOP in Moscow;

- manufacturing double "Vibram" boots at the Moscow Sports Inventory Factory with special nutrition powered by mercury-zinc batteries.

Communication with the wall was regular, twice a day (at 8:00 and 20:00); attempts to establish communication with the "Vysochnik" camp using "Nedra" were unsuccessful.

In addition to the radio station, the team had flares (green and red); emergency communication was scheduled for 12:00, and an unscheduled radio contact was arranged upon a green flare signal.

Reception on the "Vitalka" radio was excellent throughout; some difficulties arose due to the station's sensitivity to temperature changes. A frozen or sun-heated "Vitalka" would categorically refuse to work. We quickly got used to this feature and, before making contact, would place the station in an inner pocket to normalize its temperature.

Chronicle of the ascent

July 29, 1973

After a day's transition from kishlak Dridzh, we arrived at the colorful tents of Camp No. 1 on the moraine (5000 m). We noted with regret that some of the food and ropes were missing. Our three-week absence had tempted the shepherds. Fortunately, some reserve supplies of food allowed us to relatively easily overcome this loss.

On the plateau under the Southeast face (5200 m), a second - assault - camp was established; observers would also stay here. Provisions were packed, equipment checked and assembled. Everything was ready. Tomorrow was the start.

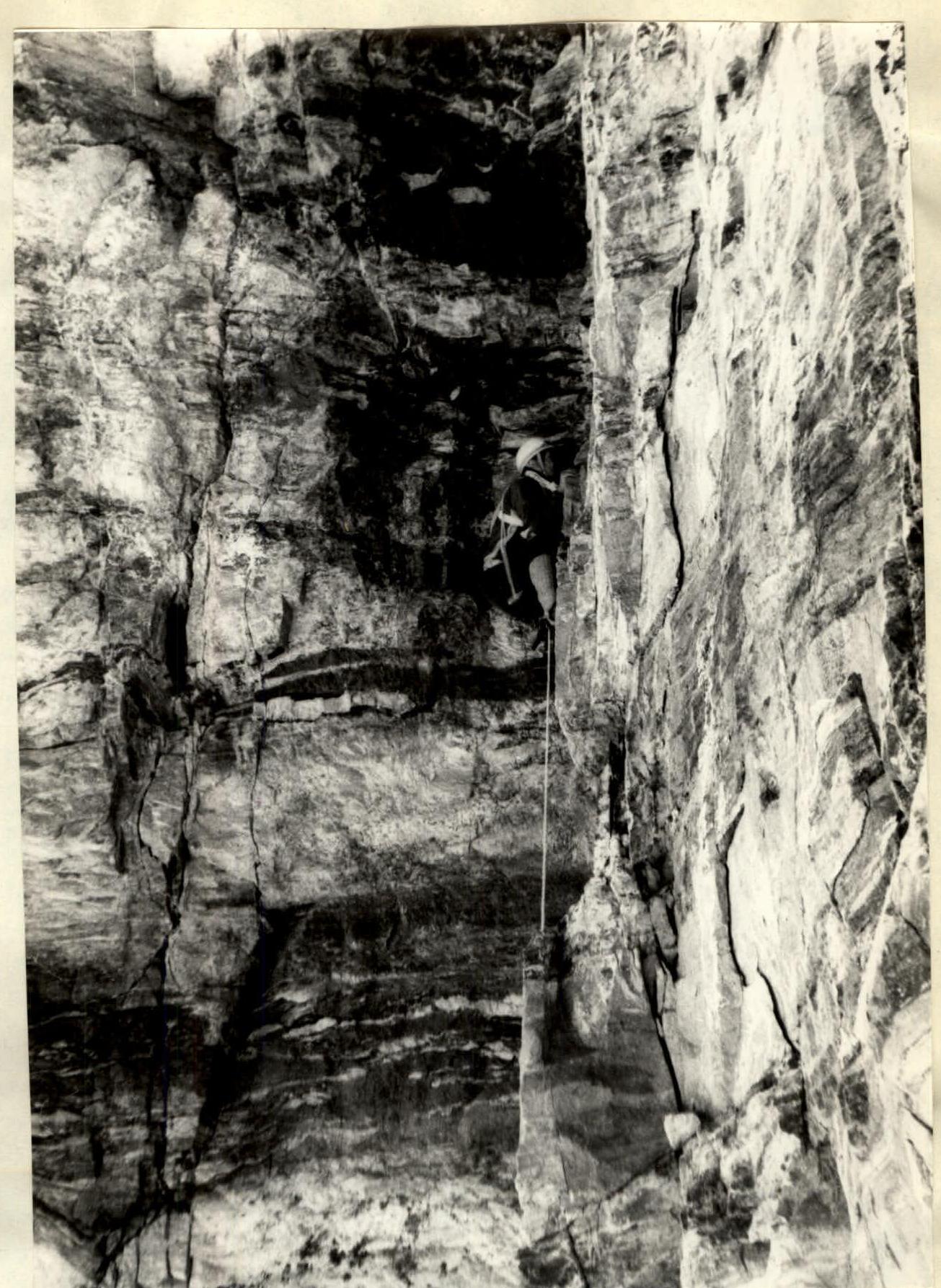

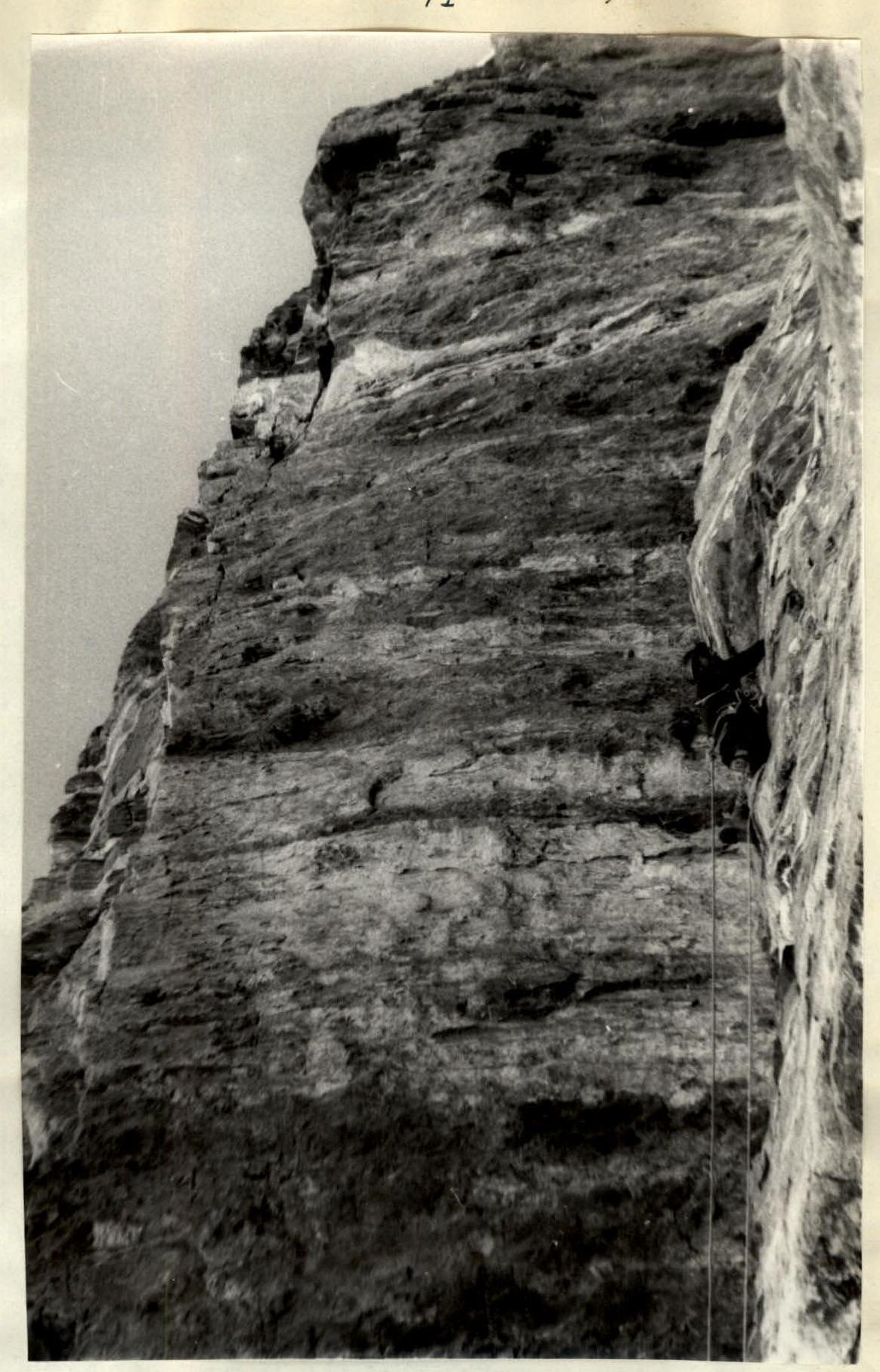

Photo 5. Entering the internal angle on the first belt. "...From the first rope, it became clear that the beginning was more complex than it seemed from below through the binoculars..."

July 30, 1973

Today was the long-awaited start of work; we could compare our observations with reality. 7:30 AM. The trio - Yura Logachev, Sasha Lipchinsky, and Lenya Troshchinenko - left the last camp, carrying three ropes and the necessary "hardware" to process the first yellow belt.

The task for the day:

- Traverse the entire belt

- Organize a bivouac on the narrow ledge visible through the binoculars

The cold early sun had already illuminated the path. Long morning shadows slowly diminished, confirming the increasing steepness of the slope. Stop. Bergschrund. Bridge. We were used to seeing horizontal bridges, but this one resembled a lifted Leningrad bridge. The close banks of the bergschrund had parted by 20 m in height.

Calga sports helped, but they were easily cut on the steep ice. Above - a hook. We left the rope here for the others to pass, as they had heavy backpacks.

Upon approaching the rocks, it became clear that challenging climbing would begin from the first meter.

Following a long-standing tradition, the first rope belonged to Sasha Lipchinsky. Within 15 meters, it became apparent that the start of the route was much more challenging than it seemed: monolithic rocks formed a sheer internal angle with very few cracks for hooks. Changing from "Vibram" to galoshes, Sasha entered the internal angle. Due to the lack of cracks, some hands instinctively reached for the hammer drill. And while such a move was being discussed below, the rope slowly crawled through four gloves - a four-handed belay.

Sasha has been on many challenging ascents with the team for years, but he had never hammered an expanding hook. The rope kept crawling, and meters turned into dozens.

Photo 6. Changing into galoshes, Lipchinsky enters the internal angle. Later, we realized that the term "internal angle" clarified little, as the entire route consisted of internal angles.

The ladder still protruded from the back pocket. Here, it was pointless - hooks every 8-10 m. The internal angle ended in a cornice, under which was a surprisingly flat, though littered with huge stones, platform 2 × 2.5 m.

Four people approached the rocks below. It turned out that Bakurov felt unwell - a decision was made to send him down with one of the observers.

It was a pity - Slava was a participant in almost all serious ascents by the team, and it was hard to imagine the organization of work on the wall without his calm, yet always active, participation.

While Lipchinsky and Logachev went higher, bypassing the cornice to re-enter the internal angle, two more climbed up the fixed ropes to the platform, and the extraction of two special bags with cargo began. Personal gear was carried in backpacks weighing 7-8 kg - a tactic the team had used since the ascent of Bodkhon in 1971.

The rope for the challenging climb - and Lipchinsky finished traversing the first belt. But it was already too late for everyone to follow; we would have to bivouac under the cornice. Meanwhile, clearing of the platform was underway there. There was no possibility of setting up tents - the platform ended in sheer walls. 0.7 m² per person, plus gear, food, and kitchen. We squeezed into the tents like into a sack, half-sitting, filling the entire ledge and entangling ourselves in a complex system of self-belay ropes. We slept very poorly due to the cramped conditions.

The first control checkpoint was left on this platform.

July 31, 1973

We woke up early - around 6:30 AM, as the sun was on the wall (though it would be gone by 1:00 PM). Around 8:00 AM, they left via the fixed ropes.

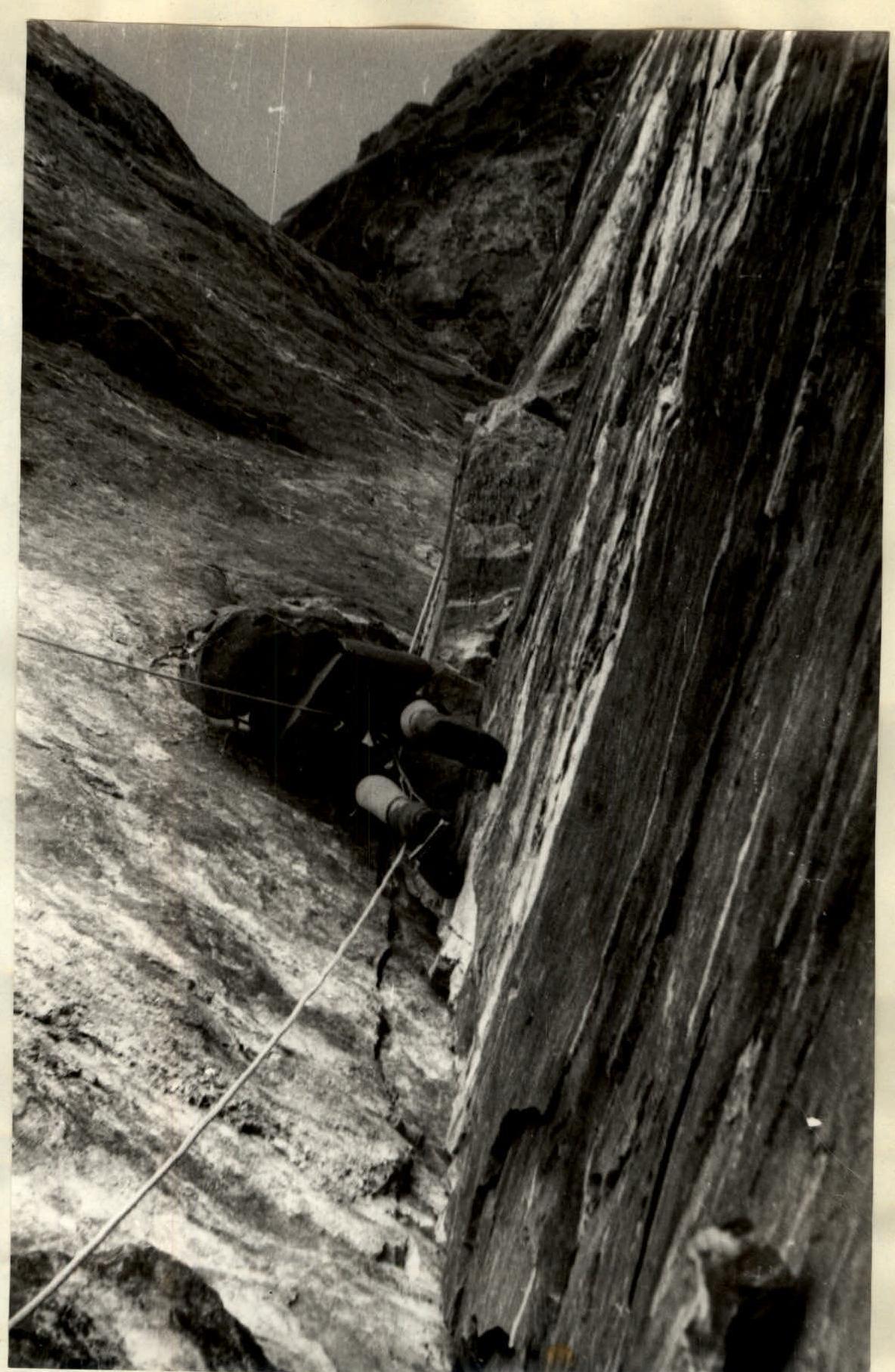

Photo 8. We finished the first belt again via an internal angle with steps - "the other way around."

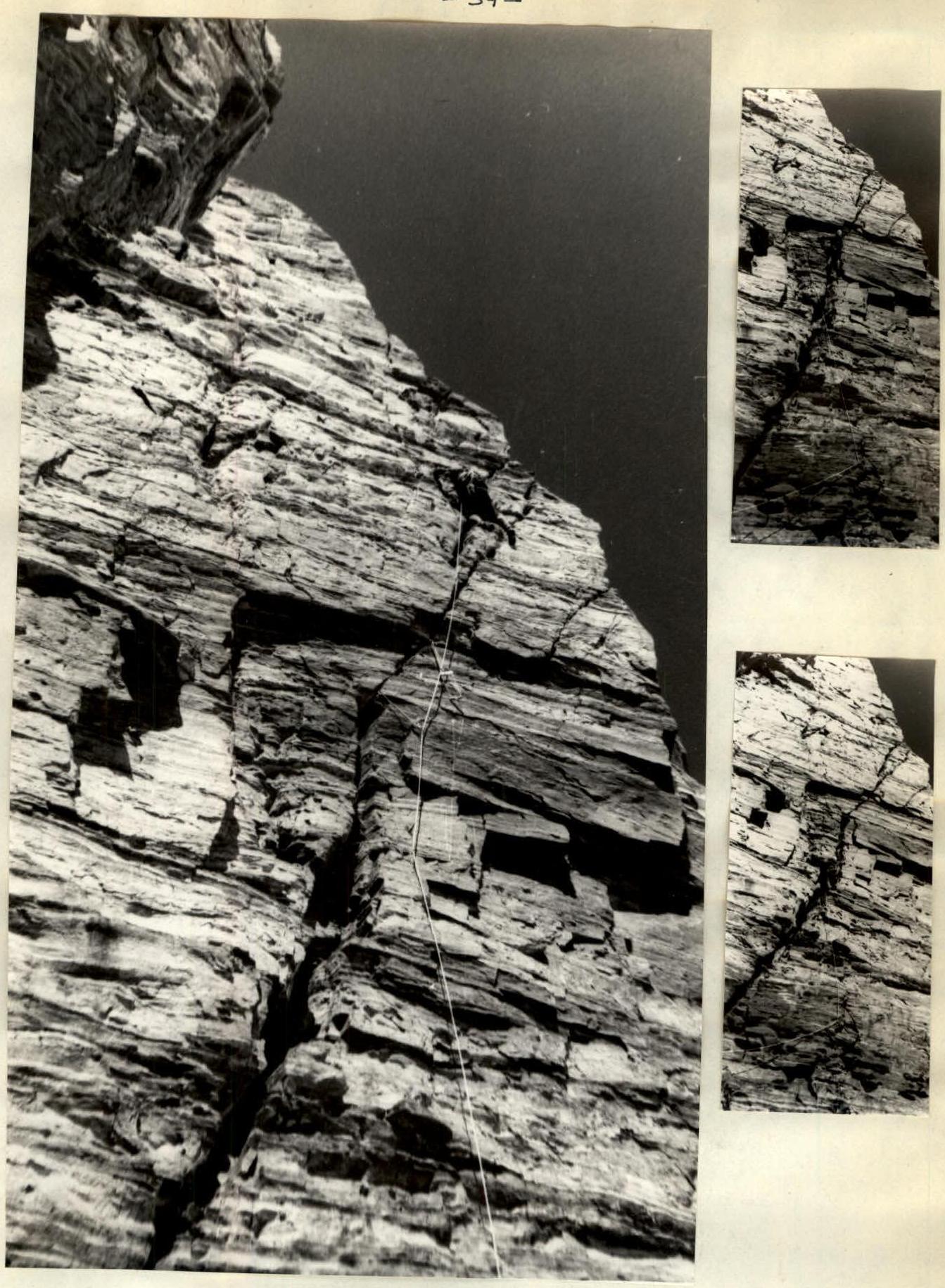

Photo 10. Chimney - and it's clogged. Sergey Kalmykov had to move to the right wall. Kalmykov and Troshchinenko planned to traverse a 100-meter chimney. During the work, we faced a complexity characteristic of the entire route: the last person often had to repeat the work of the first - navigating complex traverses, bypassing cornices, etc. This was especially true for all exits from under cornices, where loading the rope on the last person was not possible due to large "pendulums."

After traversing about two ropes through steep, crumbling, and stepped rocks, Kalmykov completely disappeared into the chimney. The walls were smooth, requiring chimney technique - it was like shooting a training film.

At the end, the chimney was blocked by a huge stone; Kalmykov exited onto the right wall, bypassing the plug (photo 10).

The new boots, made especially for this season, held well on small footholds. Cracks were often encountered. Challenging but enjoyable climbing.

The upper part turned out to be not a chimney but an inclined fissure in the wall. Here, while traversing via fixed ropes from above, a stream of small stones poured down into the fissure at the slightest movement of the rope, making it necessary to move under a continuous hail - fortunately, there were no larger stones.

Those who had been on Chatyr-Dag remembered its chimneys:

- Monolithic walls with small holds,

- A frontal wall made of reddish, very loose rock that literally flowed like an avalanche at the slightest touch,

- Impossible to hammer a hook into it or hold onto it.

The chimney on this route was similar.

While we were extracting our transport bags, Kalmykov attempted to traverse another rope, hoping for a better bivouac. Here, above the fissure, we would clearly have to bivouac one by one - or in pairs.

After traversing 20 meters through a sheer wall, Kalmykov hit a cornice. Bypassing it to the left would have required at least 5 bolt hooks. The desire to avoid them made us.

Photo 12. The desire to avoid "bolt" work made us seek other paths to bypass the cornice. To the right, 15 m away, there was a fissure, initially wide, then narrowing into a crack; although the wall clearly overhung, we decided to attempt to traverse it - it was visible that, in the worst case, it would require the use of ladders. But this was for tomorrow; for now, we proceeded to construction, which resulted in the creation of four platforms.

Next:

- Two would sleep one by one,

- Three managed to sit in a tent,

- Two lay on a narrow ledge above the wall, stretching their self-belay ropes.

By this time, the wind, gradually strengthening since midday, had reached hurricane force, carrying small stones and blowing them down from above. We practically did not sleep at night. Despite the eastern orientation of the wall, it was very cold - the wall did not have time to warm up from 7:00 AM to 1:00 PM, even in the sun.

On this bivouac, we encountered a new difficulty:

- Only in a crack did we find a small piece of ice.

- We consumed half of it,

- And left the other half for the next day.

Most likely (as it turned out), there would be no ice on the next bivouac, and we would have to lift it in a bag from here.

August 1, 1973

Lipchinsky moved up exactly along the route planned yesterday. The wind did not subside; hands froze; those sitting below wrapped themselves in tents and put on all the "down" clothing they had. Over three hours, everyone observed Lipchinsky's work, using the free time to repair the extraction bags. For the first time, Sasha needed a ladder twice to traverse a rope of overhanging rocks - truly virtuosic work, pleasant just to watch. The "perilous" ropes hung freely in the air, swaying in the wind - everyone was already accustomed to this state of free floating - every exit from under a cornice ended in this attraction. Upon reaching the top, we found ourselves on a narrow layer of sandstone, strangely wedged into the monolithic wall. We managed to widen the platform by digging into the wall and decided to bivouac here, as above us was the "Big Cornice," visible to the naked eye from below. According to our calculations, traversing it would require processing. While we hacked at the sandy rock with ice axes, Zaionchkovsky moved forward to process the entrance to the internal angle under the cornice. After 10 meters of a sheer internal angle, there was a smooth slab with rare holds, along which we had to traverse 15 meters. There were no cracks - and here appeared the only bolt hook hammered on the route. Reaching the internal angle, Zaionchkovsky secured the rope and descended to the bivouac. The comfortable sitting bivouac, hidden under the cornice, was very pleasant. It was unclear whether we would manage to traverse the gray belt with the Big Cornice the next day. We again divided the ice lifted from the previous bivouac in half - neither to the right nor to the left were there visible ledges where we could try to find ice, and above - cornices and overhanging walls. The absence of snow, ice, and even icicles could be explained not only by the great steepness of the route but also by its altitude. The snow falling here did not melt in the not-so-warm rays of the morning sun and was blown away by strong winds that practically never ceased. The average daytime temperature was well illustrated by the fact that ice, which had lain in a bag for 3 days, not only had not melted but had not even dampened the bag.

August 2, 1973

Yura Logachev and Lenya Troshchinenko went to process the internal angle under the Big Cornice. The first 10 meters were traversed exclusively on ladders - the section significantly overhung. Further.

Photo 17. Entering the internal angle under the Big Cornice. Above the cracks ended - that's where Sasha Zaionchkovsky's bolt hook appeared. The crack widened, becoming too wide for hooks (3-4 cm), but remained extremely inconvenient for climbing.

After some hesitation, having overcome the desire to use a bolt hook, Yura switched to free climbing and approached the ceiling, which protruded by about 8 meters. Having hammered one hook on a 10-meter section, he secured the rope. Along the sheer right wall of the angle, an exit from under the cornice was visible, where a small ledge was guessed. In the worst case, the bivouac could be moved there.

The climbing was challenging, on small holds. It should be noted that each belt of the SE bastion had its own relief characteristic of the rocks of that type. So, in terms of climbing technique, we had a full range:

- from blocky rocks with wide fissures,

- to smooth slabs with microscopic holds.

Above the Big Cornice, Troshchinenko moved forward. At the top, 100 meters away, an icy cornice glimmered in the sun - this cheered us up, as our ice supplies were running low, and the cornice meant an abundance of water. Hope appeared that we might reach the ridge that day. The path to it lay through another internal angle. In its upper part, it significantly overhung, but a deep chimney was visible in the left wall. It seemed we would have to climb into it. Troshchinenko traversed the lower part directly along the angle and disappeared into the chimney. He reappeared in the light only at the very top, under an overhanging stone that blocked the internal angle.

Above, the rocks were smoothed - probably, in the spring, ice slides down this angle from the ridge - through the stone, Troshchinenko exited with great care.

There remained the last belt of black rocks, which from below had seemed crumbling. Up close, it turned out to be monolithic and smooth, and also very steep.

By 4:00 PM, having traversed the last 30-meter internal angle with ice, Lenya reached the ridge.

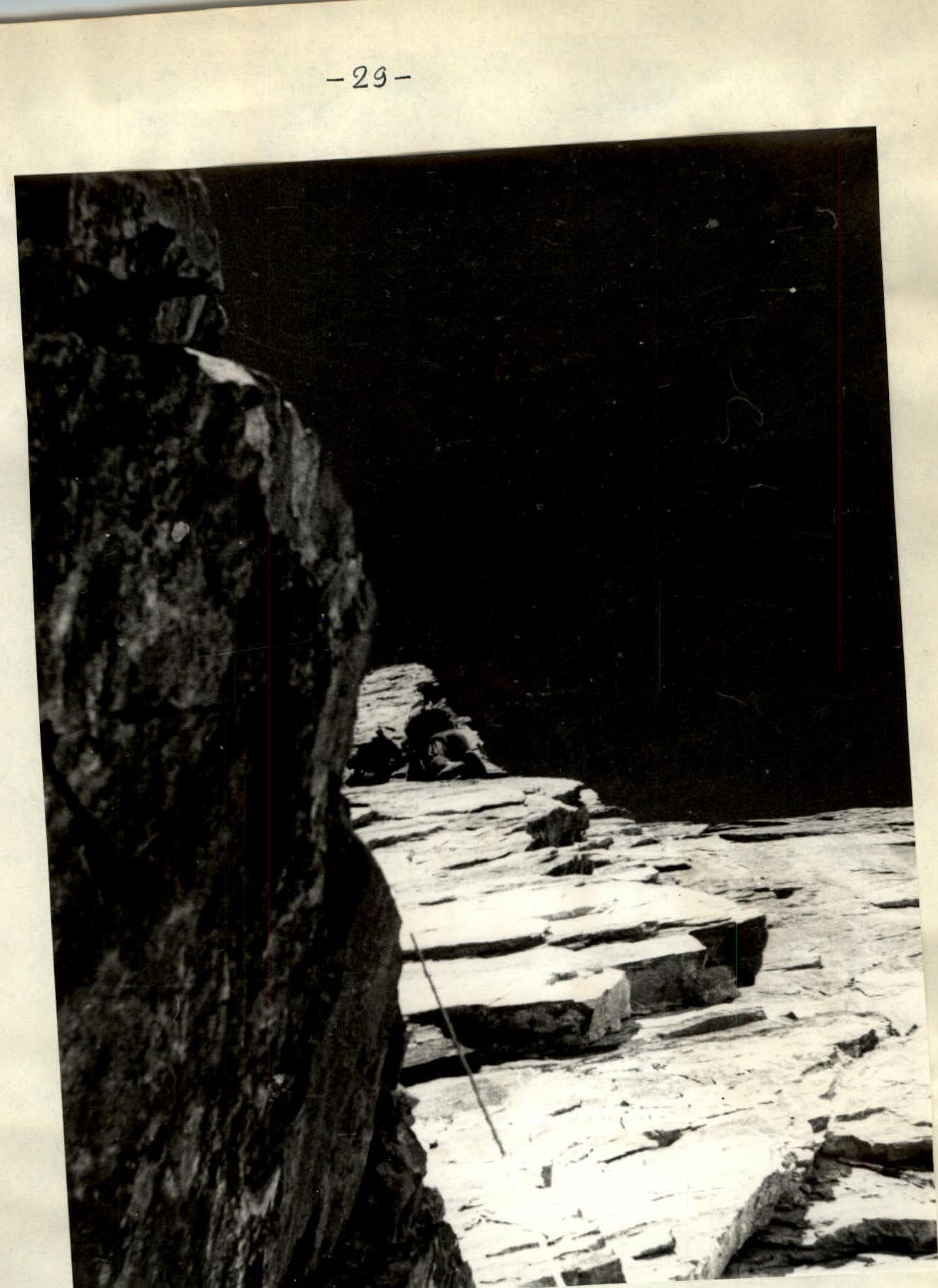

Photo 19. On the fixed ropes under the Big Cornice. At the hook... (see next photo) From here, 100 meters away, the extraction of transport bags was organized. On the tile-like rocks of the ridge, we had our first reclining bivouac. Alas, despite the comfortable platforms, we slept poorly - apparently, the altitude (6100 m) and cold were taking their toll.

August 3, 1973

The southeast ridge of Peak Tajikistan is a series of rock steps connected by ice ridges, so the tactics of movement completely changed. We left the bivouac late, giving ourselves rest after the wall work. At 9:30 AM, the rope team of Gorenchuk, Lipchinsky, and Troshchinenko moved forward. Movement was simultaneous, with hook belay; several sections required alternating belay. Climbing with "weighty" backpacks was challenging at high altitude; the pace of movement was not too great. By 2:00 PM, we reached the ice ridge leading to Peak Tajikistan. Along it, through a small dip, we reached the summit by 3:00 PM, which was a vast, even snow field. The cairn was in the far part - all traversed routes exited either from the east or northeast. In the cairn, we found a note from our group led by Vadim Lurie, who had ascended via Bozhukov's route (July 27-30). Two from that group were now with our observers.

The descent along Savvon's path to the plateau at 5100 m took about three hours. And soon, we were met by observers, who had been watching our every step through binoculars from the "5200" camp for 5 days.

After spending the night on the plateau, we dismantled the camp, and by the evening of August 4, we were waiting for a car on the road at kishlak Dridzh.

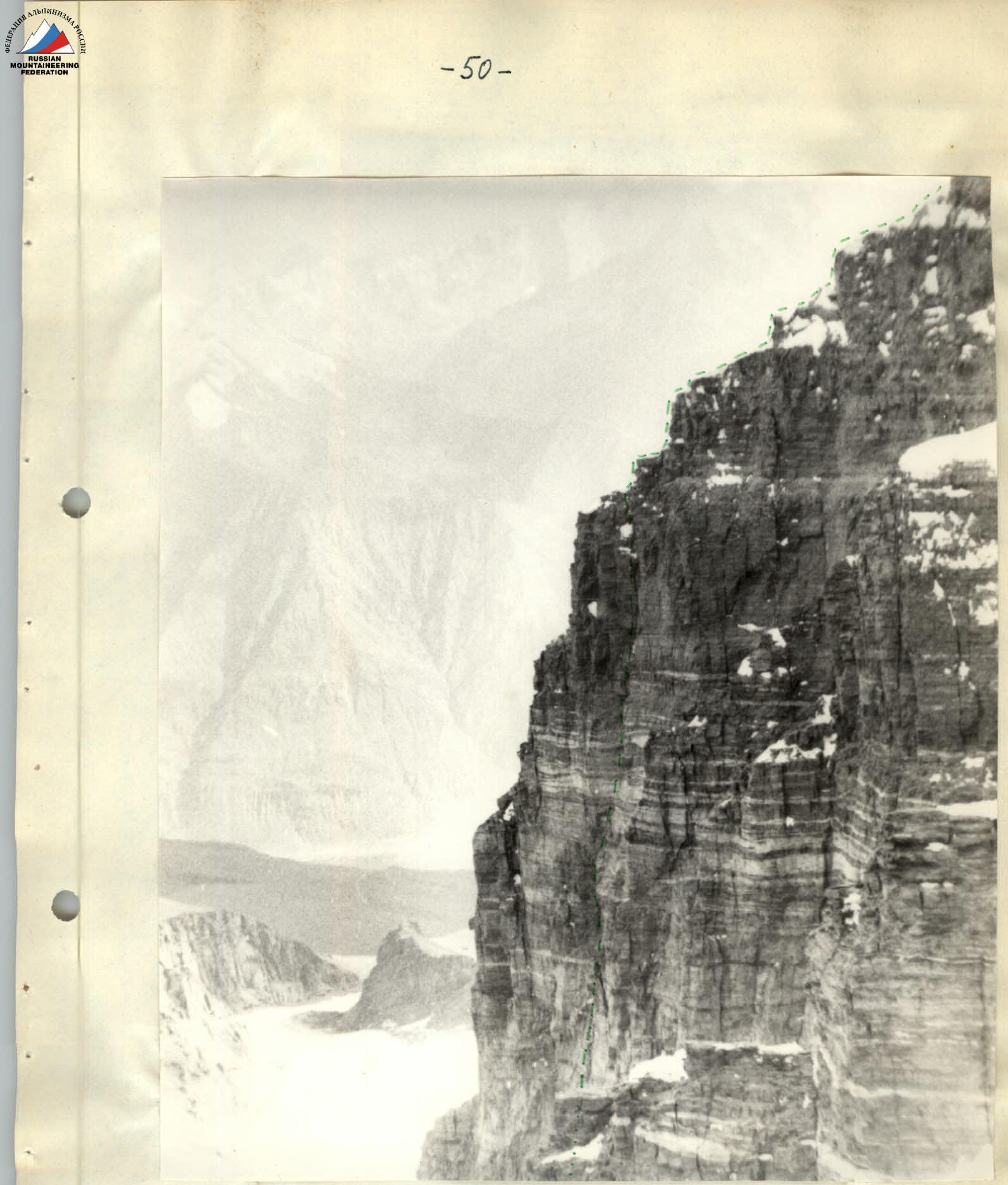

Photo 24. Upper part of the face and start of the ridge. Taken from the eastern ridge of Peak Tajikistan. The lower part of the face is hidden by the Small Bastion.

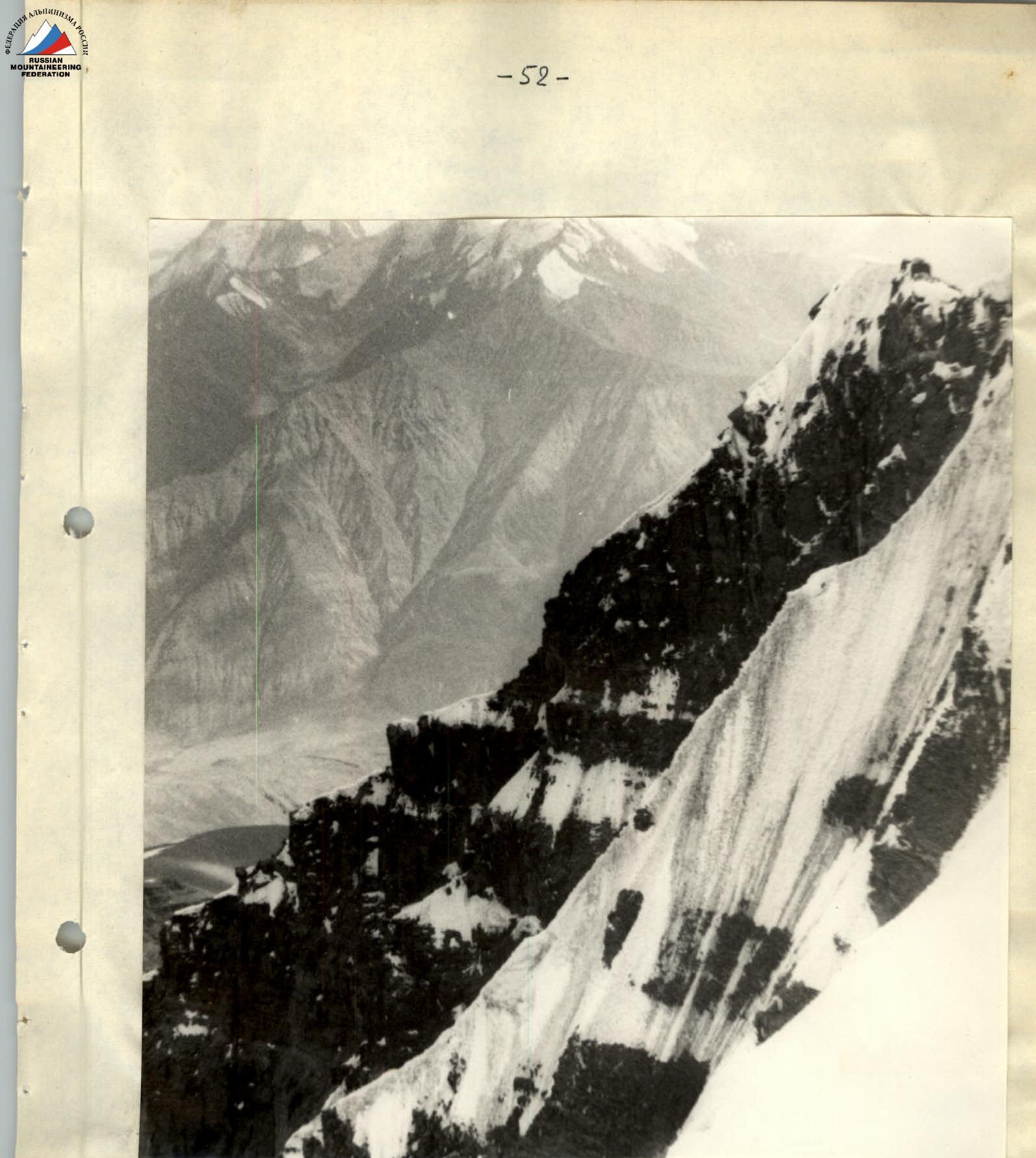

Photo 26. Southeast ridge leading to the summit of Peak Tajikistan.

Route assessment

When assessing the complexity of the route on Peak Tajikistan via the SE face, it should first be noted that, by the nature of the work on the wall section, this route falls more into the "technical" class. If one disregards the fact that the 650-meter wall starts at an altitude of 5450 m and ends at 6100 m, the wall section itself represents a complex ascent in the "technical" style. The steepness of the wall is unusual for the high-altitude and technical class (more than 80°), and its length is one and a half times that of such a classic technically complex route as Myshlyaev's path on Chatyr-Dag.

According to general opinion, a comparison of the wall with the northern face of Chatyr-Dag is most natural, with the only difference being that while Myshlyaev's route is characterized by chimneys, the SE face is characterized by internal angles. Essentially, the entire route consists of a sequence of internal angles connected by traverses or exits from under cornices.

It should be said that such an extent of the wall section does not mean that the route via the SE face "falls out" of the high-altitude and technical class. Comparison with routes like the one through the center of the SE face of Peak Engels (Maltsev, 1972) or the route through the center of the wall of Peak OGPU (Khudyakov, 1972) shows that the steepest sections are concentrated between the marks of 5300-5400 m and 6000-6100 m. So, the SE face of Peak Tajikistan (with a steep part from 5450 to 6100 m) with consideration of the overall height of the peak and the difficulties associated with altitude fully fits into the high-altitude and technical class.

The complexity of climbing on the entire wall section of the route, except for three ropes, can be classified as category 6B.

The technical complexity of the ridge leading to the crest of Peak Tajikistan is within the 5th category. Overall, the route via the Southeast face of Peak Tajikistan, through the center of the Big Bastion, undoubtedly corresponds to category 6B.

Team Captain: Yu.A. Logachev

Senior Coach of the team: F.N. Zhitenev

Table of main characteristics of the route to Peak Tajikistan 6565 m via the Southeast face

Height difference 1250 m Total length 1600 m Most challenging sections 650 m Average steepness of the wall 83° of the ridge 50°

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| July 30, 1973 | ||||||||||||||

| R0 | 150 м | 40° | snow slope | easy | simultaneous | clear | 7:30 | \ | \ | \ | \ | \ | \ | \ |

| R1 | 10 м | 60° | ice bridge over bergschrund | challenging | hook belay | \ | \ | \ | 1 | \ | \ | \ | \ | \ |

| R2 | 80 м | 45° | ice slope | medium difficulty | fixed ropes | \ | \ | \ | 2 | \ | \ | \ | \ | \ |

| R3 | 25 м | 80° | slabs into an internal angle | difficult | free climbing, hook belay | \ | \ | \ | 2 | \ | \ | \ | \ | \ |

| R4 | 25 м | 90° | internal angle | extremely difficult | free climbing | \ | 20:00 | 12:30 | 7 | \ | 3 | Bivouac on a platform under a cornice. Sections R5–R11 processed | \ | 650 г |

| Total for the day 290 m |

Table of main characteristics of the route to Peak Tajikistan 6565 m via the Southeast face

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| July 31, 1973 | ||||||||||||||

| R5 | 5 м | 100° | traverse on overhanging rocks | extremely difficult | free climbing, windy hooks | clear 8:00, strong wind | \ | \ | 1 | \ | \ | \ | \ | \ |

| R6 | 20 м | 100° | internal angle with 2 small cornices | extremely difficult | free climbing | \ | \ | \ | 4 | \ | \ | \ | \ | \ |

| R7 | 5 м | 110° | traverse back into an internal angle | extremely difficult | free climbing | \ | \ | \ | 1 | \ | \ | \ | \ | \ |

| R8 | 15 м | 90° | internal angle | extremely difficult | free climbing | \ | \ | \ | 2 | \ | \ | \ | \ | \ |

| R9 | 10 м | 90° | traverse onto a ledge | very difficult | free climbing | \ | \ | \ | 1 | \ | \ | \ | \ | \ |

| R10 | 20 м | 70° | narrow inclined ledge in a 70° wall | medium difficulty | free climbing | \ | \ | \ | 3 | \ | \ | \ | \ | \ |

| R11 | 5 м | 90° | wall | difficult | free climbing | \ | \ | \ | 1 | \ | \ | \ | \ | \ |

| R12 | 30 м | 50° | crumbling rocks | medium difficulty | free climbing | \ | \ | \ | 3 | \ | \ | \ | \ | \ |

| R13 | 25 м | 80° | entrance to a chimney | medium difficulty | free climbing | \ | \ | \ | 6 | \ | \ | \ | \ | \ |

| R14 | 25 м | 90° | chimney with smooth walls | very difficult | free climbing, chimney technique | hurricane wind | \ | \ | 4 | \ | \ | \ | \ | 650 г |

| R15 | 40 м | 85° | right wall of the chimney | difficult | free climbing | \ | \ | \ | 6 | \ | \ | \ | \ | \ |

| R16 | 40 |