Dedicated to the 100th anniversary of V. I. Lenin's birth

Report

on the traverse: Peak 6200 – Peak E. Korzhenevskoi – Peak Chetyrekh, made by the team of the Dnepropetrovsk Regional Committee for Physical Education and Sports on July 28 – August 15, 1969, for the USSR Climbing Championship 1969 in the traverse category.

The traversed peaks are located in the northwestern Pamir, in the Muk-su river basin. The most significant meridional ridge of the Pamir – the Academy of Sciences Range – branches out in its northern part. From Peak Akhmat Donish (6665 m) to the northwest, a powerful spur extends, bearing the peaks:

- Peak Chetyrekh (6380 m);

- Peak E. Korzhenevskoi (7105 m);

- Peak 6200. After Peak 6200, the spur sharply descends towards Muk-su.

These three peaks form a vast barrier separating the Fortambek valley from the Mushketov and Ayu-Dzhilga valleys. The valleys of the Moskvina, Korzhenevskoi, Mushketov, and Ayu-Dzhilgi glaciers and their tributaries deeply cut into the rocks of the barrier, forming steep, often sheer slopes with height differences of up to 3000 m.

The lack of access to the middle reaches of the Muk-su river, the inaccessibility of the valleys, and the steepness of the slopes have made the alpine exploration of this area challenging.

Peak E. Korzhenevskoi, discovered in 1910 by N. L. Korzhenevsky, was only conquered in 1953 by an expedition led by A. S. Ugarov under the auspices of the All-Union Central Council of Trade Unions. Around the same time, a group led by Ya. Fomenko ascended Peak 6200 from the Korzhenevskoi Glacier1. Peak Chetyrekh was first conquered, apparently, by an expedition from the "Trud" Sports Society in 1961 from the Moskvina Glacier.

In the 1960s, several routes were established to Peak E. Korzhenevskoi from the south, southwest, and southeast, from the Fortambek valley.

Particularly successful were the expeditions of the "Trud" Sports Society in 1961 and the "Burvestnik" Sports Society in 1966. The "Spartak" Sports Society team, led by P. Budanov, in 1966 ascended to the saddle under Peak Akhmat Donish from the Ayu-Dzhilga valley and first traversed the peaks of the spur – Peak Chetyrekh and Peak E. Korzhenevskoi – descending into the Fortambek valley.

The height of the peak noted in the report of this group, which we found, was indicated as 6300 m. After clarification, subsequent maps and the "Yearbook" listed the height as 6200 m, although some diagrams show other values. An aviation altimeter we had confirmed the height to be around 6200 m.

Source: Yearbook "Pobezhdennye vershiny" (Conquered Peaks), 1954, p. 400.

Finally, after several unsuccessful attempts (by teams from the Leningrad "Burvestnik" and the Tomsk Regional Sports Committee), an expedition from Donetsk in 1968 first established a route to Peak E. Korzhenevskoi from the most inaccessible side – from the Mushketov valley, via the counterfort.

In their report, the team noted that "there is no safe path other than along the counterfort, in our view. And even this path is truly safe only after prolonged stable weather"2.

The sporting objectives set by the Dnepropetrovsk climbers in 1969:

- attempt to find a new path to Peak E. Korzhenevskoi from the Mushketov Glacier;

- make the first traverse of the entire massif from northwest to southeast – were considered as interesting as they were challenging.

1. Terrain Features

The slopes of the massif are extremely steep, dropping into the Mushketov and Ayu-Dzhilga valleys, forming huge cirques with walls 2–3 thousand meters high.

Characteristic features of the area include:

- powerful glaciation;

- abundance of hanging glaciers on steep slopes;

- widespread cornices hanging from ridges.

As a result of ice and snow collapses, avalanches frequently occur down the cirque slopes.

The peaks of the massif are separated by saddles at around 5500 m, with ridges featuring numerous rock outcrops in the form of:

- gendarmes;

- wall-like exposures;

- ridges.

At the same time, the upper rock cover is heavily fragmented, significantly complicating movement and belaying.

2. Weather Conditions

On the ridges adjacent to the Mushketov Glacier, constant strong winds from the west and northwest are characteristic. The persistence of these winds leads to the formation of powerful snow cornices.

The high altitude of the peaks results in low air temperatures even in sunny weather. Therefore, on the ridges, sections of wind-compacted firn and ice often alternate with:

- areas of powdery, loose snow in wind-sheltered locations.

3. Remoteness

The area of the Fortambek, Mushketov, and Ayu-Dzhilga valleys is one of the most difficult to access in the Pamir. There are no bases or nomadic camps nearby; the nearest settlement is Altyn-Mazar, which is a long and dangerous journey away.

However, the use of helicopters as a means of transport and the presence of a reliable radio station significantly "bring closer" the base camp to settlements. Currently, all expeditions to this area are delivered exclusively by helicopter.

4. Exploration of the Area

The peaks of the massif are most explored from the Fortambek valley side, from where 5 routes have been made:

- to Peak E. Korzhenevskoi, categories 5B and 5A;

- to Peak 6200 (from the Korzhenevskoi Glacier);

- to Peak Chetyrekh, 6380 m (along the western ridge, category 5A).

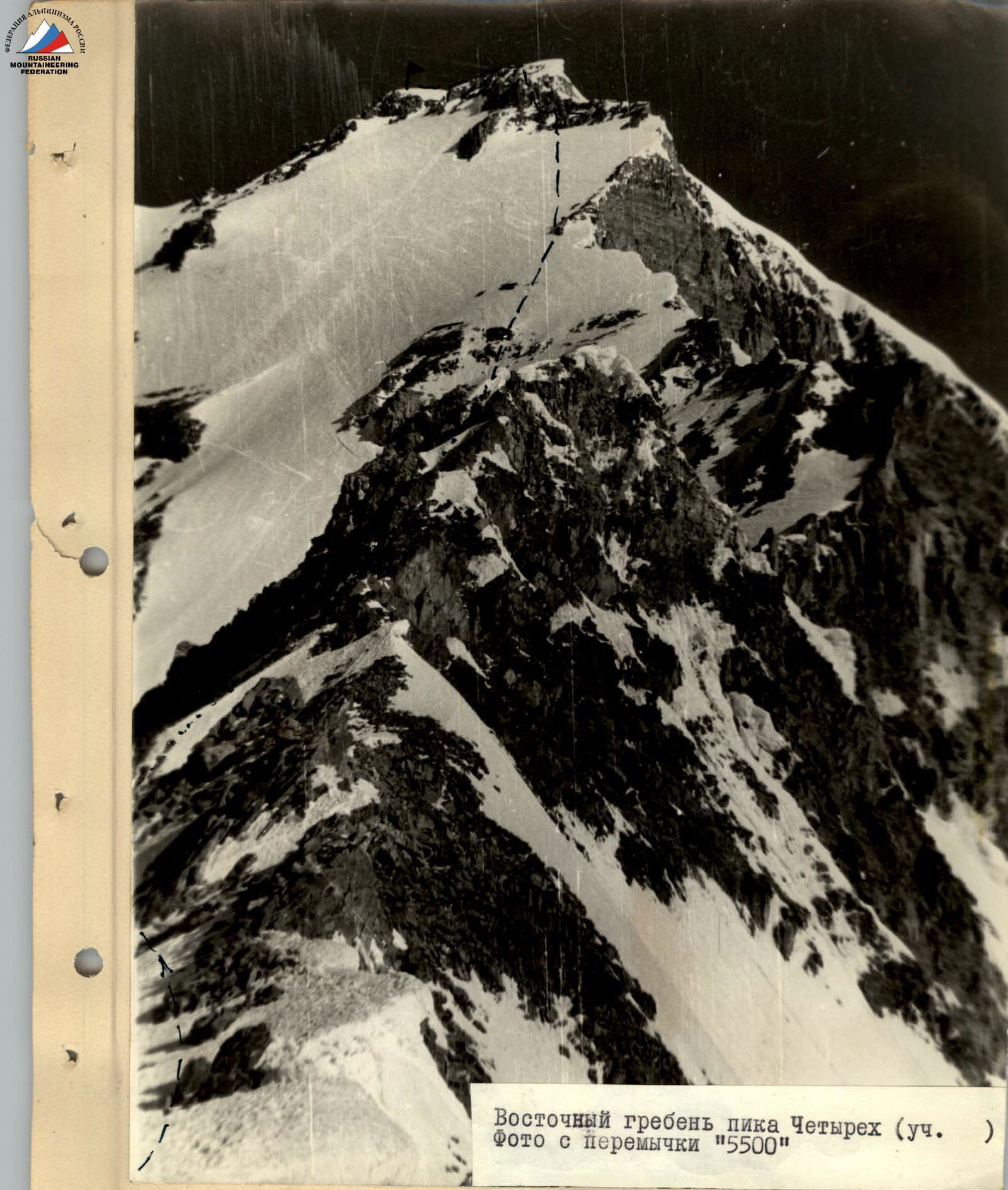

Exploration from the Mushketov valley is much weaker, with only one route made (to Peak E. Korzhenevskoi, via the counterfort), and from the Ayu-Dzhilga valley, also only one route, with ascent along the eastern ridge to Peak Chetyrekh and then to Peak E. Korzhenevskoi.

The Mushketov valley, particularly the left (orographic) branch of the Mushketov Glacier and Peak 6200, has very scarce data. The Ayu-Dzhilga valley, visited previously only by P. Budanov's group, also has very limited information, especially regarding:

- the saddle between Peak Akhmat Donish and Peak Chetyrekh;

- the adjacent ridges.

There have been no ascents on Peak 6200 since 1953; for Peak Chetyrekh, since 1961, we are only aware of the ascent by the "Spartak" Sports Society team in 1966 (we retrieved the notes left by this group on Peak Chetyrekh, as well as the note left by the first ascenders on Peak 6200)[^3]. On July 12, 1969, after flying by helicopter from Dzhirgital settlement, an inspection was made of the mouth of the Mushketov Glacier and an overflight of the traversed peaks. Then, a landing was made at the designated base camp location by the advance group consisting of A. Sinkovsky and V. Pechenin, who over the next two days:

- reconnoitered;

- clarified the general terrain features around the base camp.

On July 15, after transporting the entire expedition to the "3500" base camp in the upper reaches of the Mushketov Glacier, a helicopter was used to deliver supplies and fuel to the saddle between Peak Chetyrekh and Peak Akhmat Donish.

On July 16–17, two groups conducted an in-depth reconnaissance of possible ascent routes from the Mushketov Glacier:

- One group, led by V. Pechenin, ascended via the left (orographic) branch of the Mushketov Glacier to beneath the slopes of Peak 6200.

- The second group, led by A. Zaidler, ascended via the right branch of the Mushketov Glacier to beneath the northeastern slopes of Peak E. Korzhenevskoi.

The reconnaissance and overflight results, combined with previously available data on the traversed peaks, allowed the expedition's coaching council to draw the following conclusions:

- the slopes of Peaks E. Korzhenevskoi and 6200 facing the Mushketov Glacier, due to the heavy snowfall of 1968–1969, have accumulated vast amounts of ice and snow. Frequent icefalls and avalanches occur;

- under these conditions, ascending via the northern counterfort (the Donetsk route) with a prolonged traverse of the complex ridge along steep snowy slopes is very dangerous. Routes ascending via the northeast edge or the eastern ridge, as well as all other routes from the Mushketov Glacier that go along steep slopes or indistinct ridges, pose no less danger. Safe movement is only possible along the top of clearly defined ridges, away from the avalanche and icefall zone;

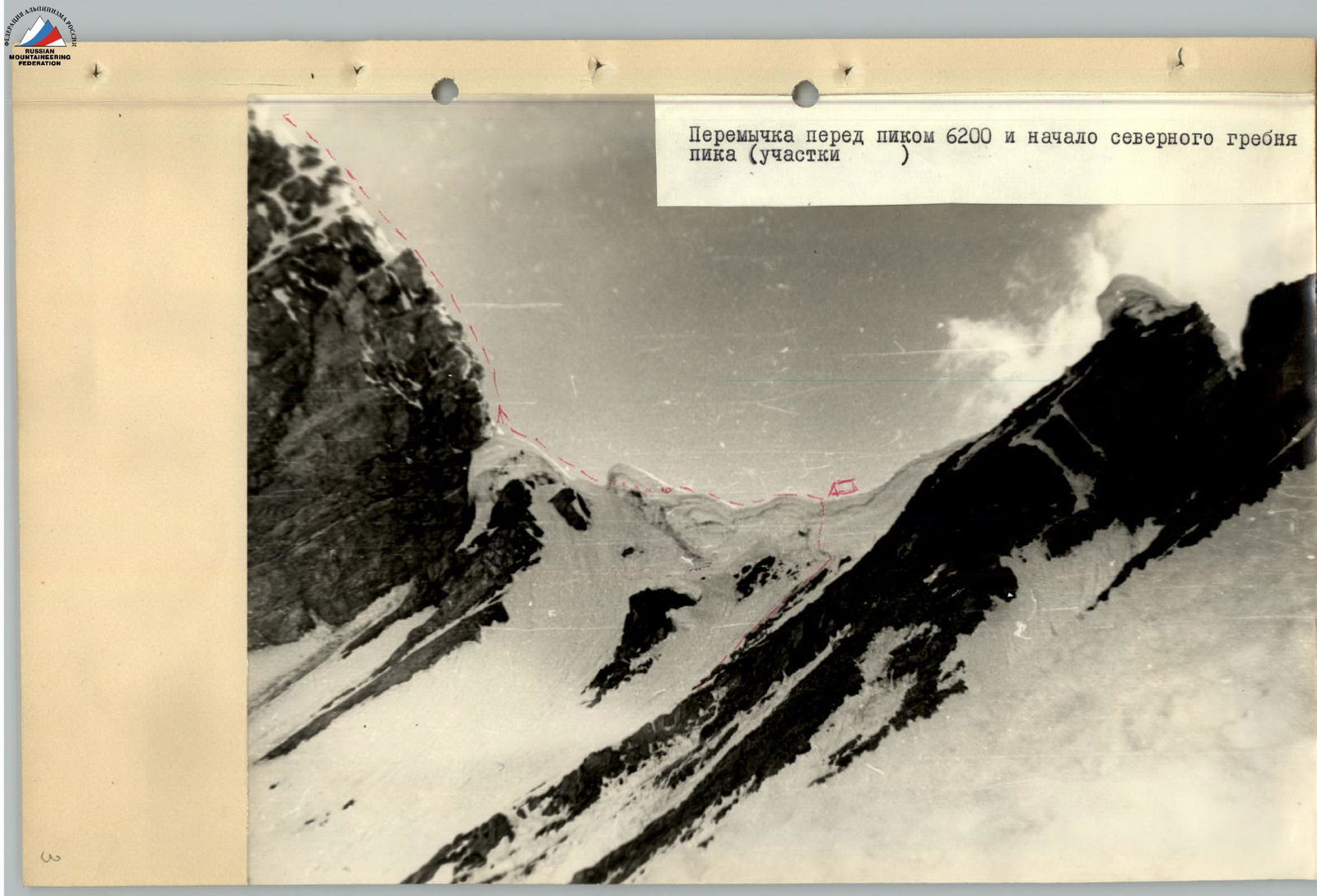

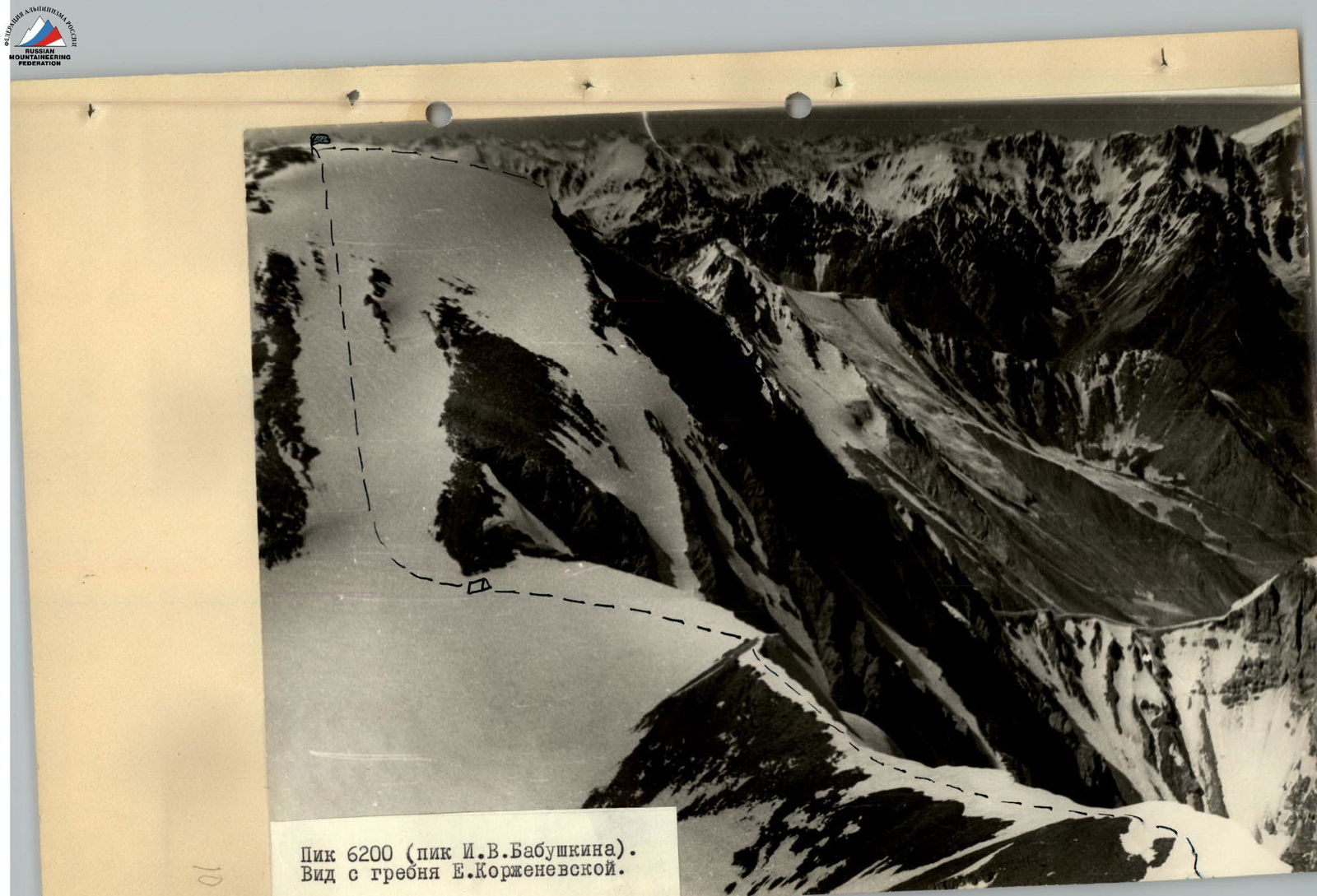

- the newly considered route to Peak E. Korzhenevskoi via Peak 6200, which follows a distinctly expressed northern ridge, meets these requirements. The further path also proceeds along ridges, allowing for a complete traverse of the spur's peaks. A steep couloir leads to the base of the ridge, which appears passable and safe. Doubts remain about the high technical difficulty of the ridge, which drops to the saddle above the couloir with nearly vertical rock faces. In any case, this is the only objectively safe ascent route for us[^4], and we decide to follow it. We begin preparing for the supply sortie.

July 19. At 14:00, we set out from the "3500" base camp with heavy backpacks. The goal is to supply products and fuel as high as possible along the ridge of Peak 6200, and if possible, to the peak.

Climbing participants:

- A. Zaidler

- V. Pechenin

- V. Shabokhin

- V. Prudnikov

- A. Malyarenko

- I. Grabar

- G. Verbitsky

- L. Artyushenko

- A. Sinkovsky

V. Lazebny remained at the base camp. The group reached the start of the couloir ascent in 4 hours.

July 20. We set out at 8:30 and spent the entire day ascending the couloir. Movement here is safe along the convex scree in the middle of the couloir. In the upper part, it becomes steep, and the scree gives way to ice. We have to transition to rock ledges to the left, hammering in pitons and setting up ropes. By the end of the day, the last ledge leads us under the cornice overhang on the saddle. After breaking through the cornice, the group emerged onto the snowy platform of the saddle at 20:00.

The team from the Leningrad City Physical Education and Sports Committee, led by S. M. Savvon, who arrived at the Mushketov Glacier a few days after us, came to the same conclusion.

July 21. From 10:00 to 17:00, the teams:

- A. Zaidler – V. Pechenin;

- A. Malyarenko – V. Prudnikov processed the rock and ice on the ridge and hung rope ladders. The group processed the route up to around 5300 m, then descended for the night.

The organizational plan for the traverse, refined after reconnaissance and the acclimatization-supply sortie, provided for the following:

- After a prolonged rest, the assault group sets out on the route, accompanied by a backup support group that follows 1–2 days later.

- The support group includes a doctor with medical supplies and equipment.

- Daily signalling with the base camp and support group using flares at 21:00 (portable radios proved unreliable during reconnaissance and supply).

After the assault group passes Peak E. Korzhenevskoi, a second support group is sent from the base camp to the saddle in the right (orographic) branch of the Mushketov Glacier, where they exchange signals with the traversers.

Thus, continuous observation of the assault group during the traverse is ensured. The base camp maintained stable daily radio contact with Dushanbe.

The tactical plan for the traverse included:

- The assault group moves to the 5600 m supply cache lightly, following the pre-installed ladders.

- Maximizing the reduction of backpack weight through the use of lightweight gear and concentrates.

- Rest days after traversing each peak.

- Carrying sufficient food and fuel to withstand bad weather.

The assault camp before Peak E. Korzhenevskoi was planned to be set up as high as possible, behind the false summit, to allow time after reaching the summit to:

- survey the descent route;

- organize an overnight stay.

The descent from Peak E. Korzhenevskoi was planned to the right of the eastern wall, following the ascent route of P. Budanov's group. After Peak Chetyrekh, having collected the supplies and fuel cached on the saddle by helicopter, the group would:

- continue the traverse to Peak A. Donish.

The group's descent was planned into the Ayu-Dzhilga valley.

It was decided to proceed in two teams: Zaidler—Pechenin—Shabokhin (first team and tent) and Grabar—Prudnikov—Malyarenko (second team and tent). Each team had with them one 80-meter auxiliary rope. Given the nature and condition of the route, each participant wore crampons.

The organizational and tactical plans for the traverse were carried out; however, upon reaching the saddle under Peak A. Donish, the group discovered that the ridge leading from the saddle to the peak, gradually transitioning into a slope, was periodically blocked by icefalls from the hanging glacier above. Having the cached supplies and fuel, the group took a rest day on August 2–3 to observe the route, which confirmed the icefall risk along the planned path.

After prolonged discussion, the group decided to abandon the ascent to Peak A. Donish due to objective danger and began their descent into the Ayu-Dzhilga valley on the 16th day of the traverse.

The group had new equipment, including:

- titanium rock and ice pitons;

- duralumin lightweight shovels;

- saws;

- ladders.

Tubular screw ice pitons made of titanium and lightweight snow saws proved particularly effective.

The original composition of the assault group as per the application:

- Zaidler A. M., Master of Sports — captain;

- Sinkovsky A. B., Master of Sports — participant;

- Pechenin V. M., Master of Sports — —;

- Lazebny V. G., Master of Sports — —;

- Verbitsky G. G., Master of Sports — —;

- Shabokhin V. A., Master of Sports — —;

- Prudnikov V. K., Candidate for Master of Sports — —;

- Malyarenko A. A., Candidate for Master of Sports — —.

Adjustments made to the group composition before the ascent: a) Master of Sports Sinkovsky A. B., who had been ill for several days at the base camp, and Master of Sports Lazebny V. G., who had undergone surgery in the spring of the current year, were not cleared by the expedition doctor, L. M. Almaz, to participate in the traverse; b) Before departure, Master of Sports Verbitsky G. G. caught a cold and was also withdrawn from the assault group. In his place, Candidate for Master of Sports Grabar I. A. was introduced as a reserve participant.

Thus, the final composition of the assault group was:

- Zaidler A. M., Master of Sports — captain;

- Pechenin V. M., Master of Sports — participant;

- Shabokhin V. A., Master of Sports — —;

- Prudnikov V. K., Candidate for Master of Sports — —;

- Malyarenko A. A., Candidate for Master of Sports — —;

- Grabar I. A., Candidate for Master of Sports — —.

July 28. At 6:00, we begin our ascent through the couloir before the snow softens. We move lightly, unhurriedly, along the familiar route. The weather is still gloomy after recent snowfalls. We arrive at our overnight stop fairly early but won't proceed further; it's not worth getting tired, as tomorrow will be a challenging day, and there are no other overnight options higher up.

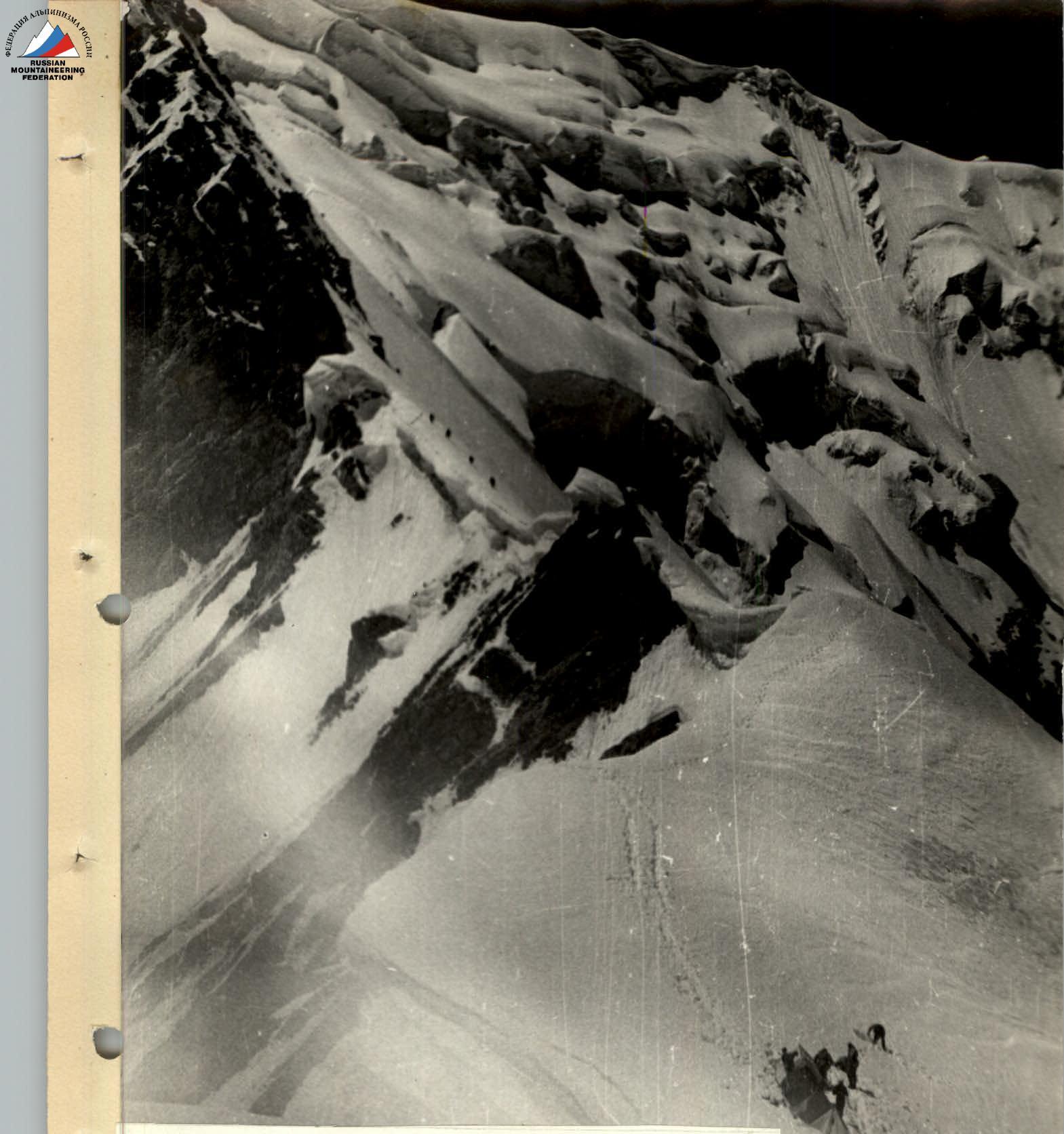

July 29. We set out at 9:00. A strong, cold wind from the northwest drives clouds across the saddle. We trudge through fresh snow along the ridge, careful not to stray too far left onto the continuous band of cornices, towards which we're pushed by the steeply descending right slope. After about 400 meters, we reach the base of the rocky wall on the northern ridge of Peak 6200; an iced-over rope hangs vertically from above as a ladder. The complex, heavily fragmented rocks are covered in ice and snow, requiring frequent clearing with an ice axe. Progress is not easy; we have to use the ladders.

Finally, after about three hours, the front team reaches the upper rocky outcrop. We rest here and put on crampons.

The steep ice-and-snow ridge is "adorned" on the left by enormous cornices, and on the right by a steep, avalanche-prone slope; we try to balance somewhere in the middle, belaying ourselves with ice pitons.

Fortunately, we find pre-installed ladders in the most challenging sections.

The platforms with supplies, carved into the ridge, remain intact; the tent is entirely under snow but is still in order inside.

We distribute the load among our backpacks.

Further along, the ridge becomes gentler, around 30°, but the loose snow and heavy backpacks make the ascent slow. We stop for the night under a bergschrund, above which the ridge rises again.

July 30. In the morning, it's bitterly cold, with a constant strong wind from the northwest. We set out at 10:00. We manage to cross the bergschrund via a thin snow bridge, after which we climb the steep ascent, grabbing onto snow with our hands and digging our crampons deep into the ice.

Steep ascents alternate with more gradual sections; hour follows hour as we draw closer to the summit tower. Before it lies a steep slope of almost pure ice, which we overcome with careful belaying.

While we rest in an ice pocket formed under the rocks, Viktor Prudnikov ascends without his backpack up a narrow gully in the rocky wall. Finally, a rope is secured at the top, and we climb up to the summit snow dome.

The cairn is located slightly below the summit on the Fortambek side; inside, we find a note left 16 years ago by the first ascenders, a group led by Ya. Fomenko in 1953.

We propose naming the peak after I. V. Babushkin, a student and associate of V. I. Lenin and a revolutionary, in honor of the Lenin anniversary. This was decided earlier at a general meeting of the expedition. We leave a photo of I. V. Babushkin and a commemorative pennant at the summit.

The descent is steep and tiring. We set up tents on the 5600 m saddle.

July 31 – a rest day. The duo Shabokhin–Malyarenko tramples the snow on the steep rocks of the ridge.

August 1 – at 9:00, we begin moving along the right slope of the ridge, bypassing the rocky gendarmes from below, then ascend a steep, wide snow-and-ice couloir onto the ridge. On the ridge, we encounter:

- steep, fragmented rocky gendarmes with ice saddles;

- often bypass the rocky ridge to the right.

Just before the point where the upper part of the ridge meets a huge ice-and-snow couloir, at around 6100 m, we set up camp.

We note that every day at 21:00, in response to our green flare, we regularly see flares from the base camp and the support group, which is a day's journey behind us.

August 2. We ascend the upper part of the rocks. Further, we climb a steep ice-and-snow couloir – a difficult and dangerous section. Initially, we move left along the left edge of the couloir and only after gaining about 250–300 meters in height do we begin to traverse the couloir diagonally to the right. We exit between two rocky outcrops and, bypassing the upper one to the right, enter the next steep ice couloir. We retreat back up onto the rocks, which we take "head-on," and after two hours of climbing, we reach the snow-and-ice ridge leading to the western shoulder of the peak. Here, on the shoulder, on excellent platforms used by the 1953 VCSS expedition on August 15, we set up camp "6500." We marvel at the wonderful panorama of Peak Kommunizma and the surrounding peaks.

August 3 – with an overnight stay, we move around a large rocky tower to the right and again exit onto the pre-summit ridge. We overcome several fragmented gendarmes. The pace of movement has noticeably slowed. The seventh kilometer of altitude and the relatively heavy weight of our backpacks, designed for the traverse, are taking their toll, but there are no signs of altitude sickness.

Ice-and-snow ascents on the pre-summit ridge follow one after another, interspersed with areas of loose snow.

By the end of the day, a steep ascent leads us to the western pre-summit at around 6900 m. A sharp 100-meter descent, and we pitch our tents in a snow-filled hollow.

August 4 – in the morning, Peak Lenin is visible from our camp, and opposite us stands the grand trapezoid of Peak Kommunizma. We prepare for the ascent with some excitement, hoping to reach the summit of this seven-thousander today.

From the hollow, we ascend to the right up a steep slope to the edge of the summit ridge above the southern wall to avoid ice ledges. Cautious movement along the narrow ridge is interrupted by ice overhangs. We find a narrow passage between the ice bastions, ascend again, and finally reach the summit dome.

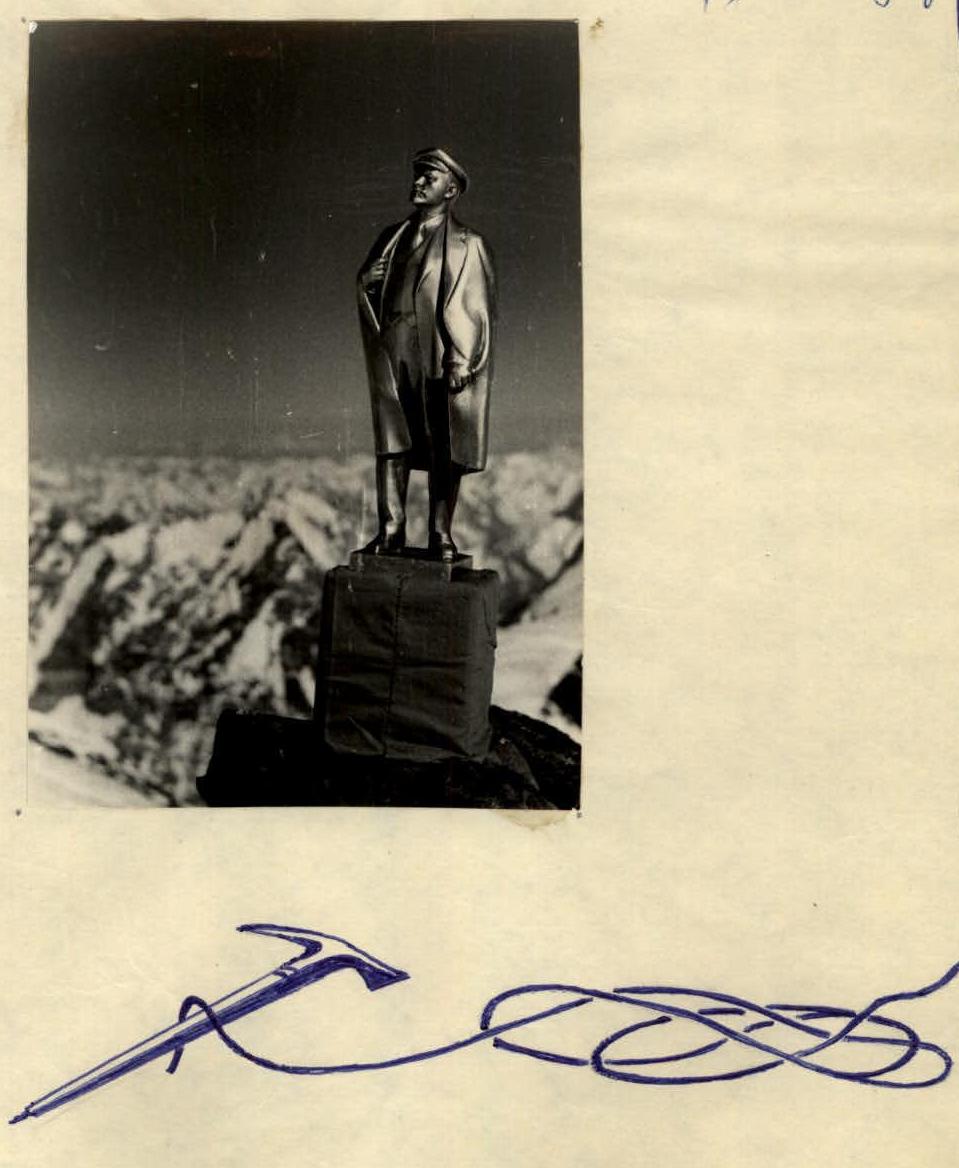

7105 is conquered!

We retrieve a bronze sculpture of V. I. Lenin and a red anniversary banner, raising them above the summit as our gift to the 100th anniversary of our beloved Ilyich.

The cairn is on the opposite side, slightly below the summit. We retrieve a note left by a group led by E. K. Zakharov on August 2 of this year, and we add our own. We carefully place the Lenin sculpture and banner inside the cairn.

After lingering at the cairn, we begin a gentle descent along the snow on the eastern shoulder of Peak E. Korzhenevskoi. At the junction of the southern ridge, on a rocky outcrop in a damaged cairn, we find a note left by B. Romanov's group in 1961 – a wooden matryoshka containing a text written in pencil from the inside. Inside the matryoshka, there's another note from Greshnev's group from the same year.

Slightly lower, on a snowy platform, we set up camp. August 5. Continuing our descent, from a broad shoulder, we enter the damaged, unreliable eastern ridge, which narrows to the point where:

- small snow cornices dislodged by us to the left cling to steep rocks, cascading 3 km down to the Mushketov Glacier;

- rocks, when dislodged, roll towards the Moskvina Glacier.

We leave the ridge to the right and descend via steep, fragmented rocks to the start of the huge "slab," which borders the triangular eastern wall from the south.

In the middle of the "slab" is a steep ice-and-snow slope; to the right and left are steep ridges of fragmented rocks. At the top, these ridges form a very unreliable, dangerous slope, covered with freely lying rocks and scree.

To reach the right-hand rocky ridge, we have to:

- traverse the upper slope down to the left.

With great caution, hour by hour, we descend along the rocky ridge, hoping for a good exit below onto the snowy slopes. Instead, at the bottom of the "slab," we encounter sheer rock drops.

As we scout the descent, darkness begins to fall. We pitch our tents on a narrow rocky ledge under the drop.

August 6. We set up a series of rappels, then move along debris-covered ledges and outcrops, and again descend via rope. We strive to escape the danger of rocks falling from above as quickly as possible.

The descent takes us further left along the route, but steep rocks continue down to the snow, and the descent takes a lot of time, especially as we're already tired.

Finally, the last descent, and we slide down the snowy slopes. We bypass a steep slope somewhat to the right and continue descending into a hollow under the saddle from which the western ridge of Peak Chetyrekh ascends. We pitch our tents on level snow, settle in, and immediately fall asleep, not even eating a hot meal.

August 7. A rest day, a dнёvka. We sleep almost the entire day, taking breaks to eat. By evening, everyone is revived.

August 8. On the morning frozen snow, wearing crampons, we fairly easily ascend to the saddle. Without stepping onto it, we veer to the right, ascending diagonally onto the western ridge of Peak Chetyrekh.

We move along the right side of the ridge, careful not to stray onto the huge cornices hanging over Ayu-Dzhilga. The ascent is not steep but tiring due to large sections of loose, deep snow. The sun begins to shine strongly; there's almost no wind today, and our guides change frequently.

We pass:

- fragmented rocks;

- snow;

- ice and firn under the snow.

At 19:00, we decide to stop for the night on a flat snowy platform, as the slope ahead becomes steeper, and there may not be suitable places to camp.

August 9. We set out at 10:00, clearly late, having overslept. The ridge beyond our camp becomes steeper; we breathe a sigh of relief as we reach the rocks, moving along them, bypassing to the right.

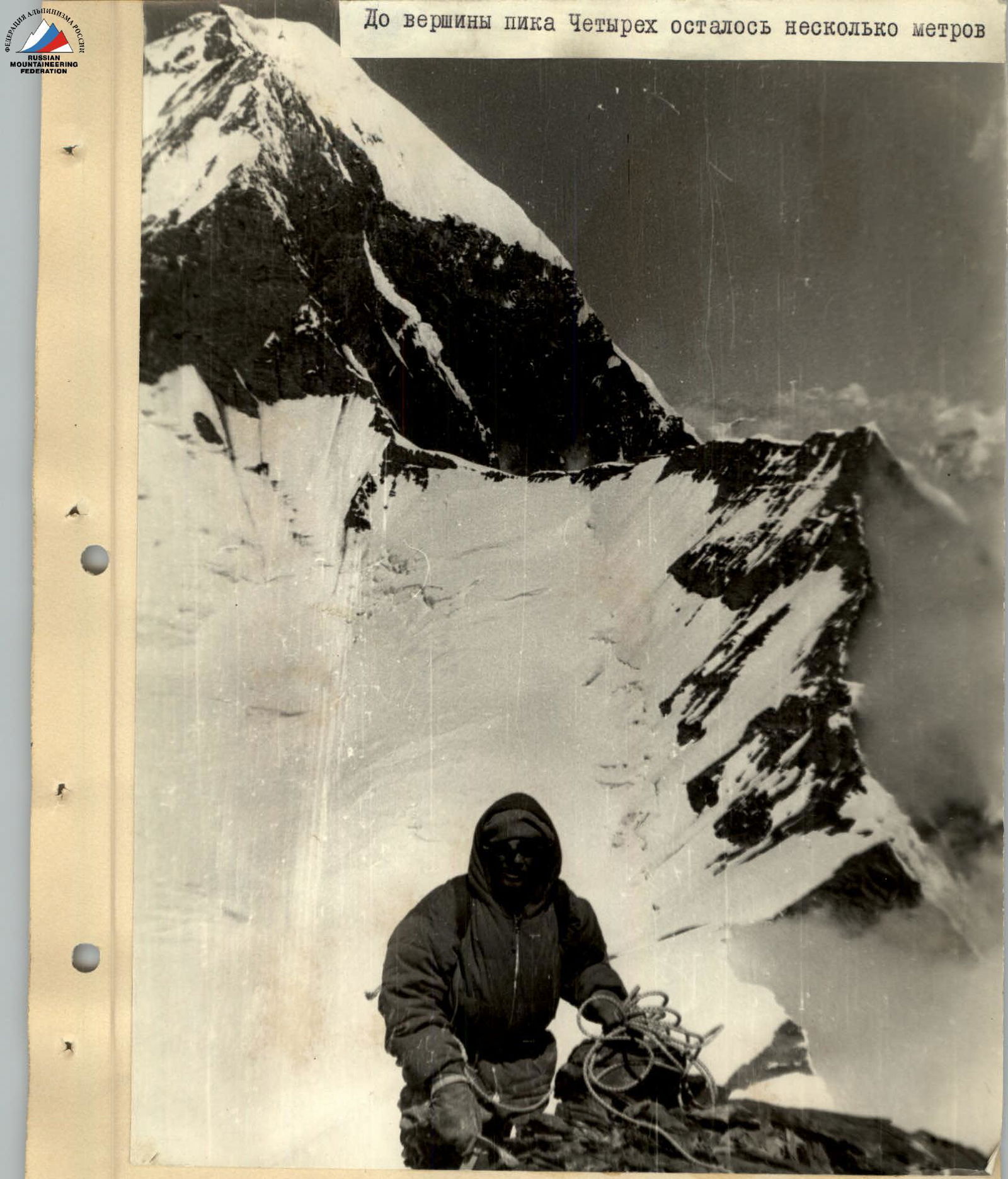

The rocks are not particularly challenging but are fragmented; we move densely, cautiously, to avoid dislodging stones onto each other. We again exit onto ice with a thin layer of snow, but we're not far from the summit tower.

At 16:00, we're at the cairn on the summit. However, this is only one of the peaks of Peak Chetyrekh; we can see three more ahead, and the highest, the true summit, is, of course, the farthest. However, the cairn is here, and inside, there's a note from O. Borisenok's group, who conquered the peak in 1966.

We spend the night in a hollow, or rather, a depression behind the first peak. August 10. Traversing the remaining three peaks of Peak Chetyrekh is not complicated, but the ascents and descents of 150–200 meters after each peak are tedious. After the fourth peak, we descend to a rocky, fragmented shoulder, from which the saddle below is visible.

We need to hurry down; there should be abundant supplies waiting for us on the saddle. However, it's precisely here that we can't afford to rush – the rocky ridge becomes steeper and transitions into a steep ice-and-snow slope.

We make several sport descents via rope fixed to ice or rock pitons, then proceed with alternating belays. The slope has softened in the sun; we move very cautiously, with screw pitons proving useful. Gradually, the slope becomes less steep, and rocky outcrops become more frequent.

To the right of the rocky ridge, we exit onto the saddle (5500) via softened snow. Here, we find the supplies, and rest.

August 11. We spend the entire day observing the ridge of Peak A. Donish. Our doubts on Peak Chetyrekh were justified: in the middle section, the western ridge of Peak A. Donish transitions into a slope, and ice blocks periodically break off from the edge of the hanging glacier above, sweeping across this slope and the upper part of the ridge.

Avalanches breaking off to the left of the main body of the hanging glacier do not hit the ridge, falling to the left onto Ayu-Dzhilga. It thunders like this every half hour to an hour.

We attempt to find a safe ascent route. August 12. After a prolonged morning discussion, common sense prevails – the group cannot take the risk of not making it through; we'll descend into Ayu-Dzhilga.

Having ascended 100 meters up the ridge from the saddle, we hang a doubled rope and begin our rappel down very steep, icy rocks. After 10–12 rappels, we find ourselves on a steep ice-and-snow slope, from which we need to move quickly to avoid rocks falling from the wall above. The slope is broken by hidden crevasses and ends in a cliff into the gorge. We have to:

- veer to the right;

- find a descent path between the crevasses;

- traverse further to the right.

Finally, we're on the upper fields of the Ayu-Dzhilga Glacier. Another 1.5–2 hours, and the group reaches the lateral moraine. Now, we have a path down the uncharted Ayu-Dzhilga.

Sixteen days have passed since we left the base camp. The traverse is complete. Evaluating the route of the first traverse – from northwest to southeast of the massif: Peak 6200 – Peak E. Korzhenevskoi, 7105 m – Peak Chetyrekh, 6380 m – it must be noted that the traverse:

- is objectively safe and logical;

- requires participants to have great endurance;

- demands the application of almost the entire arsenal of mountaineering techniques.

The high complexity, length, and altitude of the traversed route allow us to confidently classify it as category 5B.

Team Captain, Master of Sports of the USSR, Senior Instructor

(ZAIDLER A. M.) Dnepropetrovsk

(ZAIDLER A. M.) Dnepropetrovsk

September 30, 1969

www.alpfederation.ru↗

www.alpfederation.ru↗

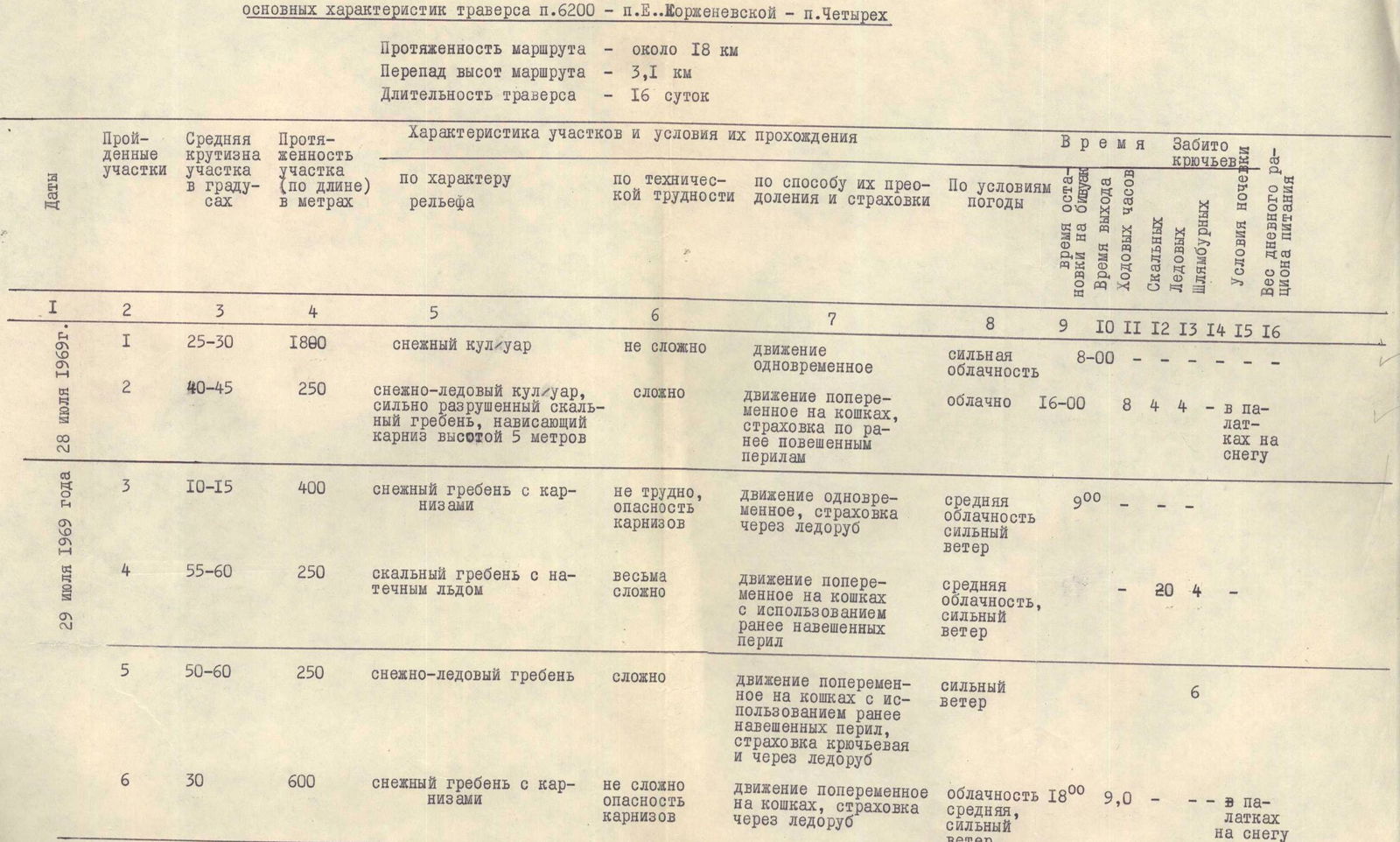

Table

Organization of the camp on the saddle. In the background, two teams ascend to the start of the northern ridge of Peak 6200.

www.alpfederation.ruwww.alpfederation.ru

Peak E. Korzhenevskoi. Photo from Peak 6200. Just a few meters left to Peak Chetyrekh!

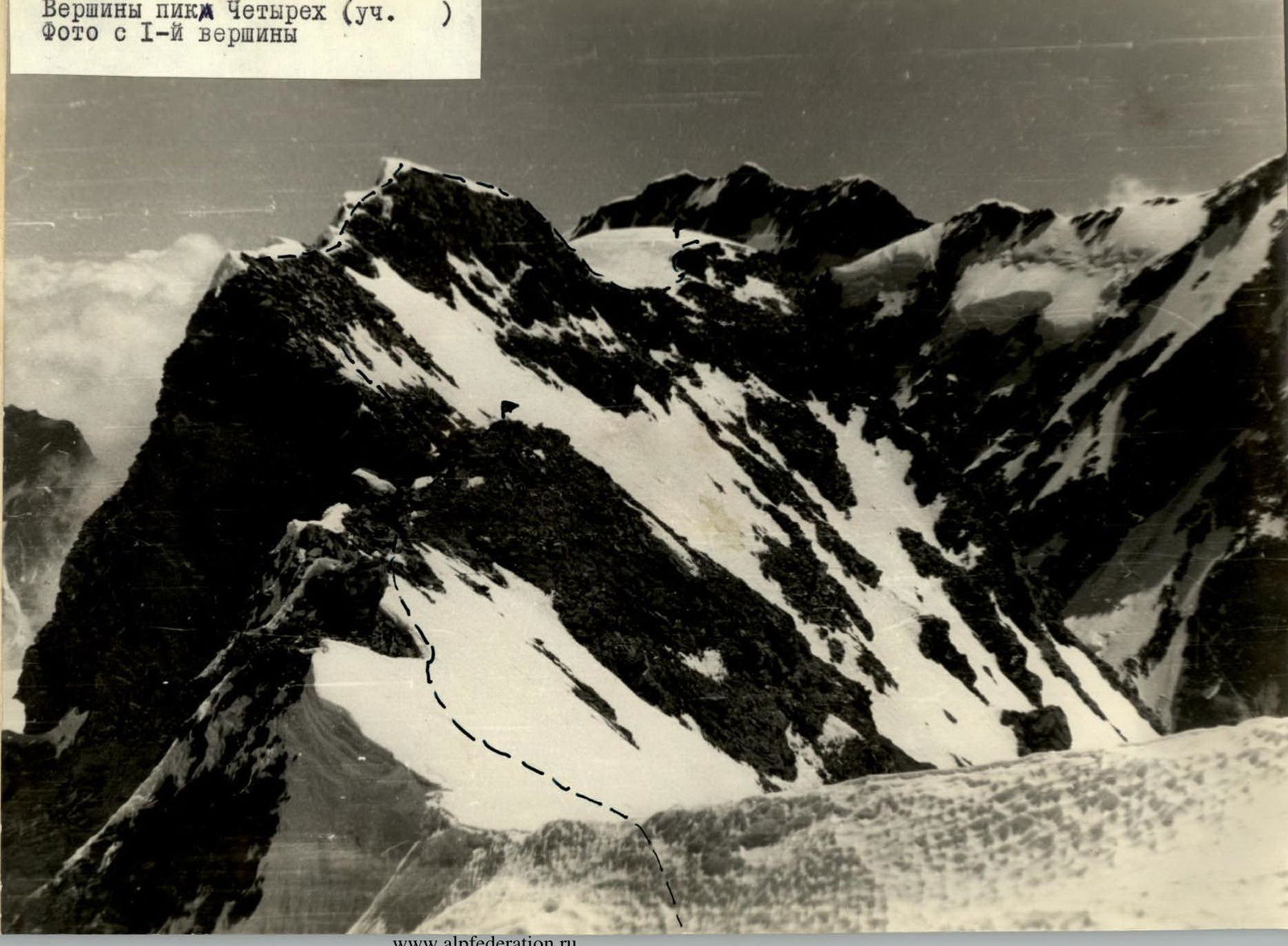

The peaks of Peak Chetyrekh (educational)

Photo from the first peak

Footnotes

-

Yearbook "Pobezhdennye vershiny" (Conquered Peaks), 1954, p. 400. We retrieved the note left by this group. The height of the peak was indicated as 6300 m. After clarification, subsequent maps and the "Yearbook" listed the height as 6200 m, although some diagrams show other values. An aviation altimeter we had confirmed the height to be around 6200 m. ↩

-

Report by the team of the Ukrainian SSR Ministry of Internal Affairs – Central Council of the "Avangard" Sports Society for the USSR Climbing Championship 1968. ↩