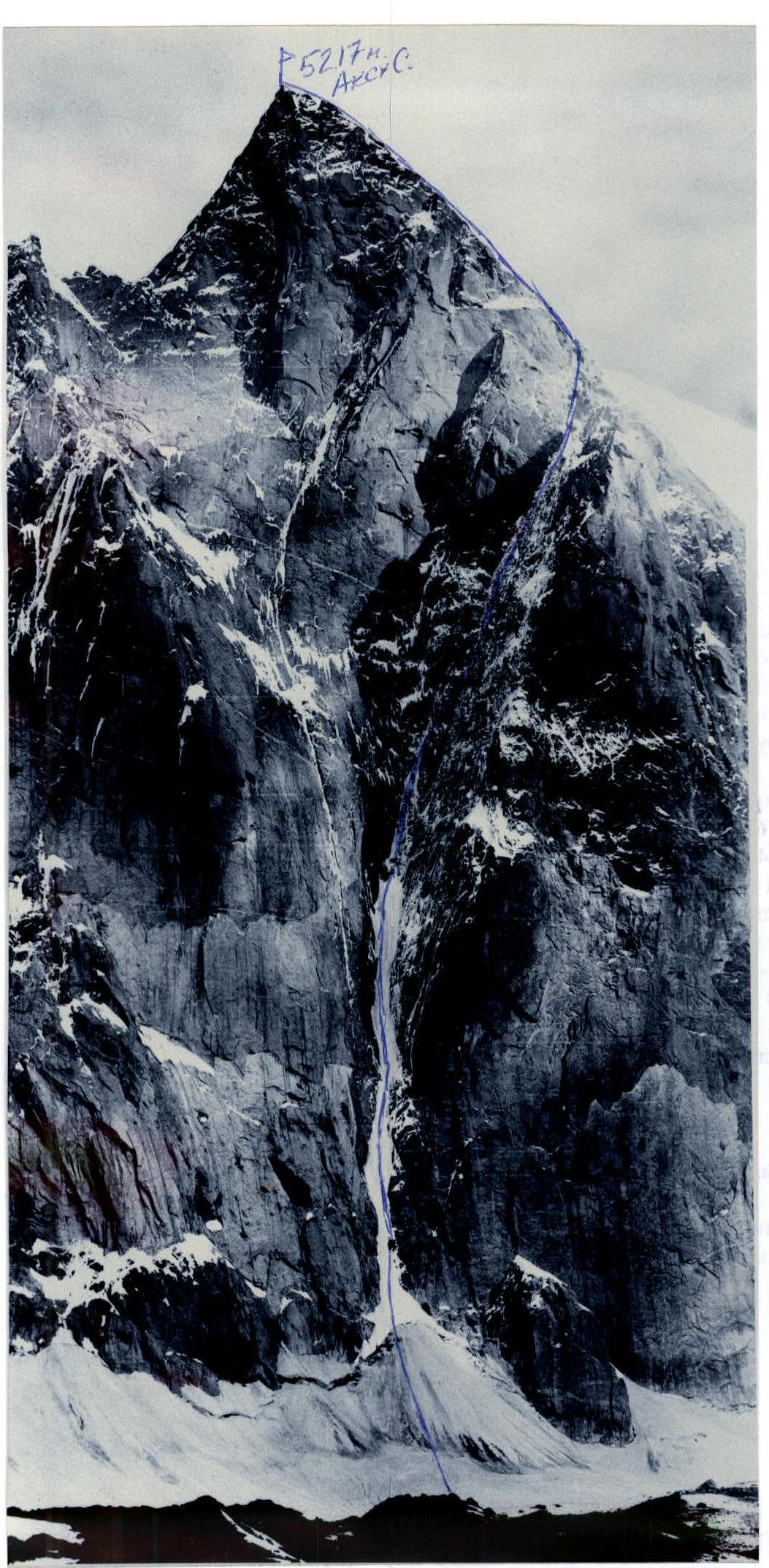

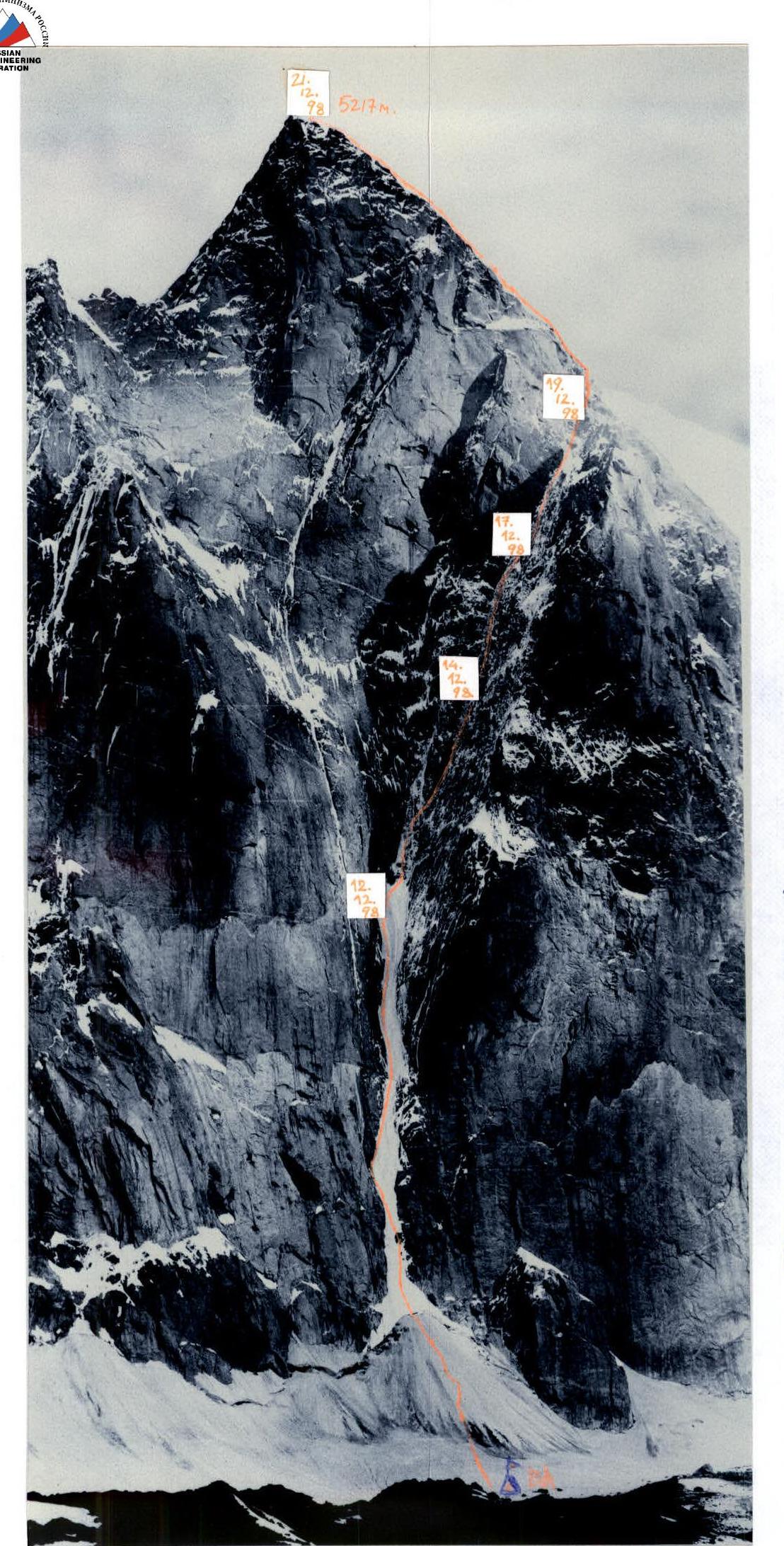

Peak Ak-su© 5217 m. To the Cold Angle on the N wall 6A cat. dif., A. Antonov, 1997 Pamiro-Alai, Turkestan ridge.

Laylak valley R5–R4–R6.

Ascent Passport

- Ascent class — winter

- Ascent area — Pamiro-Alai, Turkestan ridge, Laylak valley

- Peak Ak-su© 5217 m. To the Cold Angle on the N wall (third ascent)

- Category of difficulty — 6A

- Height difference — 1460 m.

Length — 1840 m. Length of 5–6 cat. dif. sections — 1520 m. Average steepness of the route — 61°. Walls — 67°.

- Pitons left on the route:

rock — 6 chocks — 4 ice screws — 14 (on descent) bolts — 28 (at belay stations)

- Number of climbing hours/days — 96/14

- Overnight stays: 5–15 in a platform

14 cold bivouac on a ledge 1–4 in a tent b/l (processing)

- Leader: Pavel Shabalin (Master of Sports of International Class) Team members: Ilyas Tukhvatullin (Master of Sports), Alexander Abramov (Master of Sports)

- Coach: Pavel Shabalin (Master of Sports of International Class)

- Start of ascent: December 8, 1998 Summit: December 21, 1998 Return: December 23, 1998

- Team of "RODINA" sports club, Kirov

Tactical Actions of the Team

The tactical plan for the ascent was based on the capsular style. After processing 5–6 ropes, the platform with bivouac gear was moved to the end of the processed section. The only significant innovation was the installation of belay stations with "spits" to prepare the descent route. The movement pattern of the three climbers on such a wall was traditional:

- The first climber worked on a double rope;

- The second followed on the fixed rope with top-rope protection and carried a backpack with equipment and a rope bag (American style);

- The third worked independently, transferring loads and re-rigging belay stations.

Notable equipment included:

- UIAA-certified cams "CAMALOT" and "TRANGO";

- Ice axes in special winter configuration, nitrided, suitable for both ice and rock, made by the Sverdlovsk firm "ALVO-TITAN";

- Special Thinsulate gear, which completely replaced down, produced by "RED-FOX";

- Excellent fleeces and windblock clothing, custom-made by "RED FOX" and "FILON".

Combined with "ONESPORT" boots, this allowed us to have a cold bivouac at 5200 m in winter without frostbite. Catalytic heat packs were used in critical situations. Bivouacs were organized in a suspended platform tent measuring 1.30 × 1.80 m, comfortable for three people in winter. There were no falls, injuries, or frostbite. The weather during the ascent was surprisingly good, with no days lost to bad weather. Climbing began at 10:00 and ended around 18:00.

Route features:

- Very hard, crusty ice.

- Special shortened ice screws were used for protection.

- The route condition was ideal for movement — more ice than in winter.

- Protection was more challenging.

Nutrition was standard — hot meals twice a day, dry rations during the day. High-calorie products were consumed in large quantities. Fuel was sufficient to cook and warm up. A support team of two people was stationed below during the ascent. Radio communication was regular, morning and evening. No rescue team was available.

Ascent Schedule

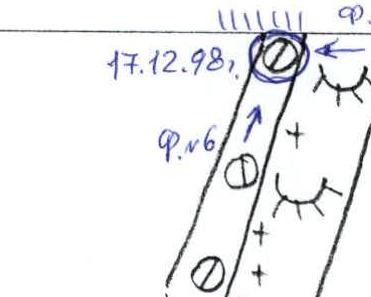

UIAA Scheme December 12, 1997

| rock pitons | chocks | bolts | ice screws | Section # | Length (m) | Steepness (°) | Cat. dif. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 | 13 | 40 | 60 | 5 | |||

| 5 | 12 | 40 | 70 | 5 | |||

| 4 | 11 | 40 | 65 | 5 | |||

| 4 | 10 | 40 | 65 | 5 | |||

| 5 | 9 | 40 | 65 | 5 | |||

| 4 | 8 | 40 | 65 | 5 | |||

| 4 | 7 | 45 | 60 | 4 | |||

| 5 | 6 | 50 | 65 | 5 | |||

| 5/3 | 7/4 | 2 | 5 | 50 | 75 | 6 | |

| 4 | 5 | 1 | 4 | 40 | 75 | 5 | |

| 3 | 3 | 45 | 60 | 4 | |||

| 3 | 2 | 45 | 55 | 4 | |||

| 5 | 1 | 45 | 70 | 5 | |||

| 2 | 1 | 4 | 27 | 40 | 75 | 6 | |

| 1 | 2 | 4 | 26 | 40 | 70 | 6 | |

| 2 | 2 | 3 | 25 | 40 | 75 | 6 | |

| 1 | 2 | 4 | 24 | 45 | 80 | 6 | |

| 2/1 | 3/1 | 2 | 23 | 50 | 85 | 6 | |

| 5/4 | 6/6 | 2/2 | 2/2 | 22 | 45 | 80 | 6 |

| 6/6 | 5/5 | 2/2 | 3/3 | 21 | 45 | 80 | 6 |

| 3/2 | 2/1 | 3 | 20 | 40 | 75 | 6 | |

| 2/2 | 4/2 | 3 | 19 | 40 | 70 | 6 | |

| 3/2 | 3/1 | 2 | 18 | 40 | 75 | 6 | |

| 3 | 3 | 17 | 40 | 80 | 6 | ||

| 2/2 | 2/2 | 2 | 16 | 40 | 85 | 6 | |

| 2 | 2 | 4 | 15 | 40 | 75 | 6 | |

| 1 | 1 | 4 | 14 | 40 | 75 | 5 | |

| 14/5 | 28/9 | 38 | 300 | 45 | 3–6 | ||

| 3 | 37 | 55 | 55 | 3 | |||

| 12/9 | 13/8 | 2/2 | 36 | 50 | 90 | 6 | |

| 3 | 35 | 40 | 60 | 4 | |||

| 3 | 34 | 40 | 60 | 4 | |||

| 1 | 4 | 3 | 33 | 45 | 70 | 6 | |

| 6/5 | 2/2 | 2/1 | 2/1 | 32 | 40 | 80 | 6 |

| 4/3 | 3/3 | 3 | 31 | 45 | 75 | 6 | |

| 2 | 2 | 5 | 30 | 40 | 80 | 6 | |

| 7 | 29 | 40 | 90 | 6 | |||

| 5 | 28 | 40 | 80 | 6 | |||

| 3 | 39 | 200 | 20 | 3 |

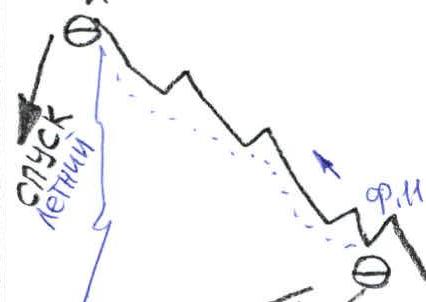

Route Description by Sections

R1–R4: The route begins with crossing the bergschrund, then two ropes up to the base of the rock belt. R4–R6: Two ropes of damaged rocks, with "ram's foreheads" iced over at the top. R7–R14: The Moshnikov ice chute is climbed along the left rocks. Belay stations are in niches-shelters. At the end of the chute — an overnight stay. R14–R16: A narrow ice gorge leads to the iced rocks of the Cold Angle. R16–R21: Indistinctly expressed corners alternate with complex walls. Climbing in crampons with ice axes on rocks, with some ITO. Challenges in organizing protection. At the end of the section — an overnight stay. R21–R25: Very difficult ropes, complicated by bad weather. The same issues as the previous day. The terrain is the same. A safe but unfavorable overnight stay — gets covered in snow. No other options — we are in the corner. R25–R31: An ice stream with an overhanging rock roof on the left. The left ice axe works on the ice crust, the right one — on rock. At the top of the section — a very steep ice forehead on a cornice. The overnight stay is again covered in snow. R31–R34: Here, ice lies not on monoliths but in destroyed corners-chimneys. At the end of the section — a complex traverse left onto a good ice chute. R34–R36: Along easy ice, we exit to the top of Moshnikov's break on the right side. Here, the routes converge. R36–R37: Straight up — very intense climbing. Cracks are either blind or between live blocks. Issues with protection organization. R37–R38: A large snow-ice ledge leads to the final rock wall, which exits onto the ridge. R38–R39: A complex ridge with gendarmes ends with a descent loop. R39–R40: From the descent loop, right along the ridge towards the summit. A gendarme is bypassed on the left, then onto a saddle and to the right side of the ridge. Through snow and easy rocks — to the summit.

On December 21, 1998, at 18:30 local time, we stood on the summit of Ak-su. Sanya Abramov — for the first time, Ilyas Tukhvatullin — for the fifth time, and for me, it was the ninth ascent up the north wall of my favorite mountain. There was one circumstance that made this ascent stand out in a long series of similar ones — it was the first winter ascent of the North wall of Ak-su.

Every year, I am drawn to the Laylak valley like a magnet. Each person has their own path in mountaineering, their dreams and plans. It so happened that my entire mountaineering life since the early 90s is inextricably linked with this mountain. Over 10 years, the most beautiful routes have been climbed, and new ones have been laid. One dream remained — a winter wall.

Three years ago, we already tried to do this. After a week of fighting bad weather and circumstances, we were forced to descend. Then I said, "Now I know how to climb this wall, but I don't know who will do it." Besides our team, there were four more attempts at a winter conquest of Ak-su. All unsuccessful. However, the time had come. The optimal time for the ascent is December. Although it's the shortest day, the weather is more stable compared to January and February. The probability of prolonged snowfalls is minimal.

The basis of the team's tactical actions is the capsular style, where for several days, the path is processed from a suspended platform — 300–400 m, ropes are fixed, and loads are transferred. The team's strategy is based on the need to stay on the wall as long as necessary: two weeks, three, a month...

We were extremely lucky. The entire ascent with processing and descent took only 16 days. We left all fuel and product supplies at the last bivouac site — on the ridge: 4 liters of gasoline, 12 kg of products. If necessary, we could have comfortably stayed there for just as long. And a bit more, albeit without comfort.

The main difference between a winter ascent and a summer one is:

- You have half the daylight;

- The speed of movement is halved;

- You have twice as many warm clothes and twice as much fuel and food;

- And everything happens much slower than in summer.

Plus one — there is more ice in winter, and it doesn't melt. However, the ice is hard. I can't imagine what I would have done with ice axes, but without ice axes, it's impossible in winter. Virtually the entire wall is climbed either on ITO or on ice axes. Protection is through shortened ice screws made by the Ural firm "ALVO-TITAN" with special winter sharpening, as regular screws are too long for narrow ice streams. Ice axes were sharpened 2–3 times a day, or even more, as you constantly switch from rock to ice and back. Crampons and ice axes were taken as spares — you never know how this hardware will behave in the cold. The stove was also a spare. Plus a gas burner to warm up the stove, plus a gas lamp. Everything was distributed across different bags so as not to be left without means of survival. There was experience in the past — four cold bivouacs on Ak-su in bad weather, albeit in summer.

Actually, I consider the main problem not technical difficulties — we had all climbed winter "sixes" before — but the problem of survival on the wall for such a long autonomous ascent without compromising the condition of all team members and slowing down the work pace. Hence, a fundamentally new approach to this ascent compared to a summer one.

On a platform measuring 1.30 × 1.80 m, it is realistic to accommodate 4 people in summer. Without much comfort, but it's livable. In winter — three.

The first attempt at a winter ascent on Ak-su provided invaluable experience. We once and for all abandoned the use of down. Three years ago, the main reason for our retreat was down. Or rather, what was left of it. Jackets, pants, and sleeping bags — everything turned into frozen lumps. Constant temperature fluctuations from plus to minus inside the platform, eternal frost on the tent walls — all this predetermined the need to descend.

This year, the firm "RED FOX" made all our warm gear from synthetic Thinsulate — a new generation material — according to our special order. It practically doesn't absorb moisture, so warm clothes remain dry. This material is already widely used by polar explorers, but mountaineers traditionally prefer down.

Specially made suits were free from typical "arctic shortcomings":

- Loose fit and not very thick filling;

- A convenient hood (for a helmet) allowed not just movement but climbing on the wall.

Two sleeping bags of rectangular shape, when connected, turned into one group sleeping bag — big, comfortable, and most importantly, always dry and warm.

Almost all mid-layers were also made of synthetic materials — fleece and windblock. The latter is interesting because it's practically windproof and breathable.

Gloves, mittens, and balaclavas made of polartec complemented the "gentleman's set".

All this gear was tested in the most extreme conditions. On December 21, we reached the summit in darkness and under hurricane-force winds and -30°C, forced to bivouac at the descent loop at 5200 m. Instead of a tent, we had a piece of polyethylene, a gas burner (which was constantly blown out by wind gusts). The night from December 21 to 22 can be considered cold.

We survived until morning under a large rock on ropes in Thinsulate jackets and descended to the platform the next day around noon, where we warmed up until the next morning. The result is clear — no one froze or got sick.

We also highly appreciated "ONE SPORT" boots, model "EVEREST".

Climbing the wall itself didn't particularly worry us, strangely enough. Concerns were about the ridge. Even in summer, winds howl there, and in winter, it's like kilometer-long flags hanging. And a roar like a jet plane. Moreover, it's not technically simple:

- Ten ropes with traverses, pendulum moves, rappels.

On December 20, we fixed 6 ropes along an ice couloir on the reverse side of the ridge and hit a rock wall 200 m long. In summer, I wouldn't have ventured there for anything — but in winter, all this overhanging rubble was somewhat frozen, and the ridge option was absolutely unappealing. We estimated our chances of getting frostbite as 10:1 on the evening before the final push. We knew what we were getting into.

The last rope was particularly memorable. Initially, 15 m of ITO over a cornice, and then another 30 m of overhanging feathers with blocks. I was afraid to touch those feathers, but I had to climb. I thought I'd make a belay between the frozen blocks, but when I touched one with a hammer, it was like a grenade exploding. The guys 30 m below on ice screws saw a crack propagate along the screws. Everything was so tense that we left the rope on descent. We didn't even bother to pull it — life is more valuable.

We descended via the ascent route. On the way up, during processing, Sasha had eliminated the belay stations and hammered in "spits" every 45 m. To find them on the return, he tied 5-meter red strings, which greatly helped on descent. He hammered in 26 bolts, and the rest (10) were rappels — the last ones at the bottom were done on ice screws. And 10 ropes on the ridge.

On the night of December 23, 1998, we finally descended.

Thanks to Korney and Lesha — guys from Tashkent. They spent the whole month with us. And met us at the bottom.

Thanks to everyone who helped, believed, and waited:

- "RED FOX" firm and Vlad Moroz;

- "FILON" and Marat Galinov;

- "ALPEX" and Arkady Klepinina.

Article from "RISK ON LINE" magazine

WWW.RISK.RU↗.

Photo Illustration of the Report

Photo # 1. December 7, 1998. General view of Ak-su wall.

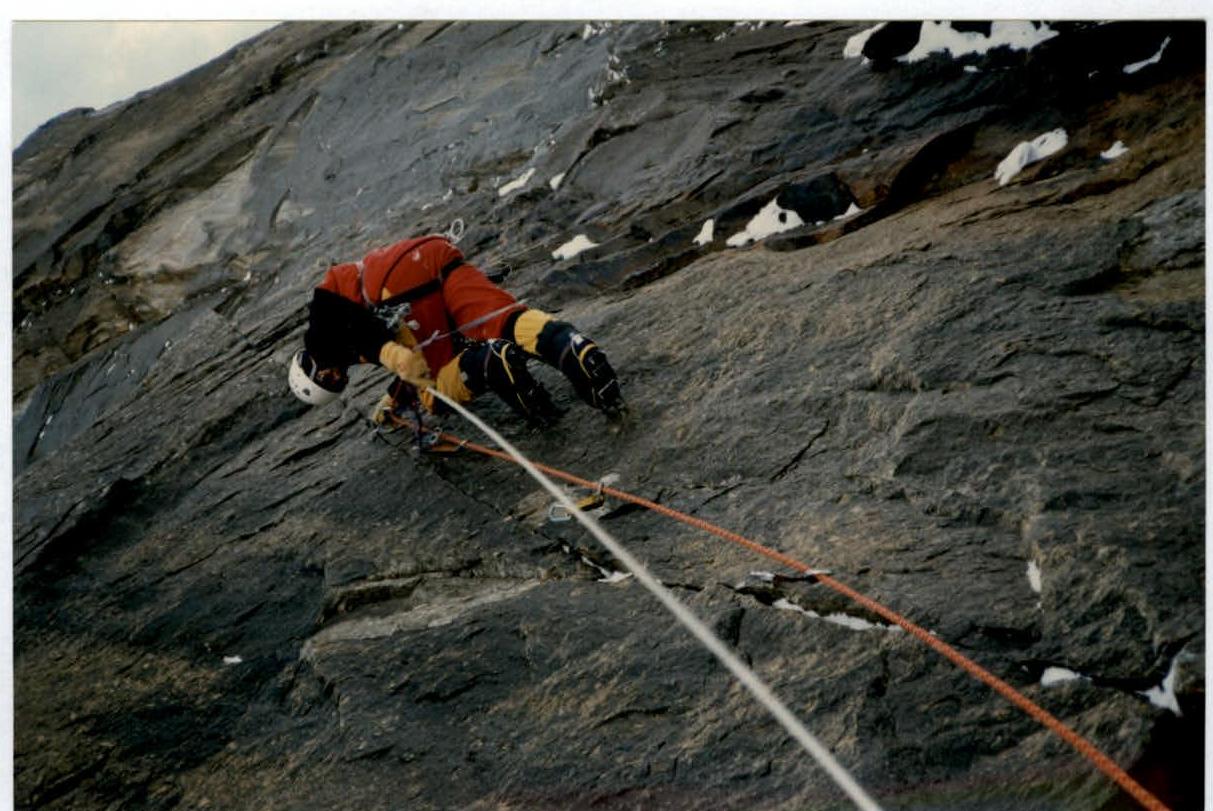

Photo # 2. Rock barrier in the ice gorge.

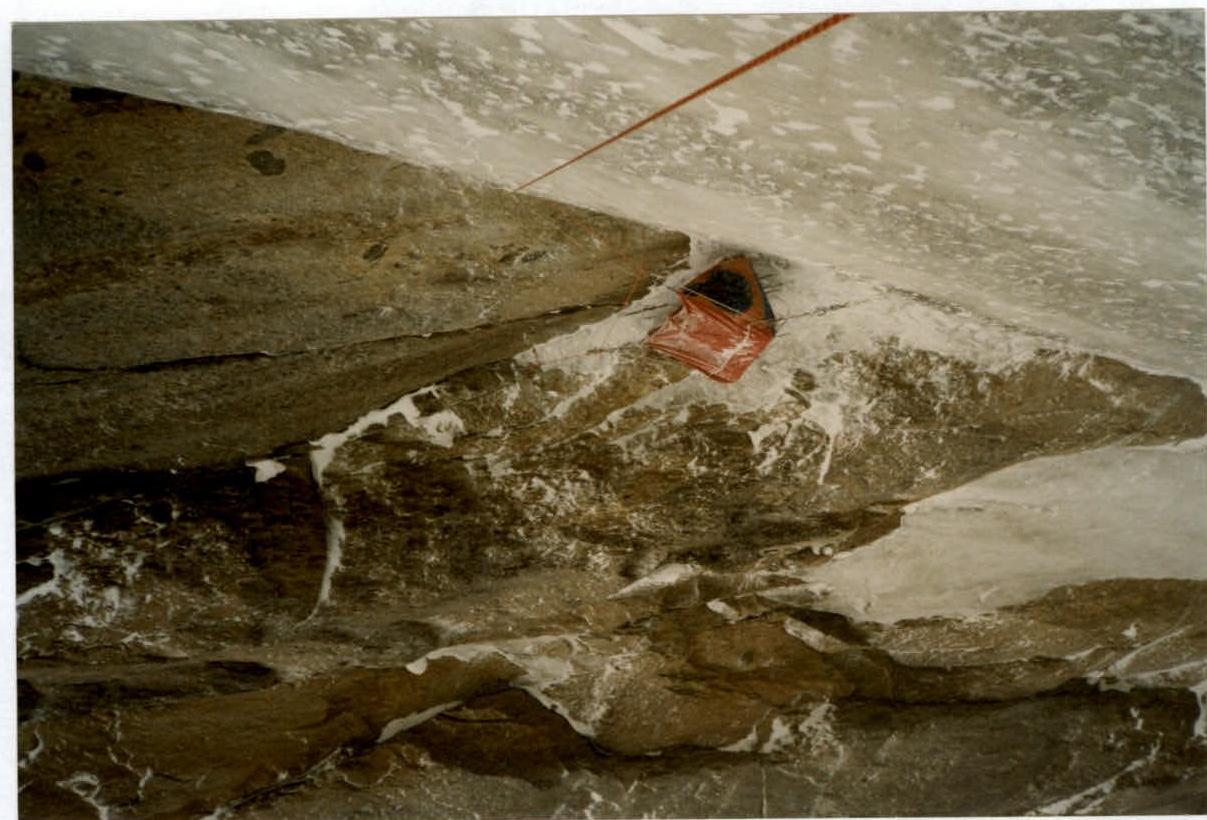

Photo # 3. Camp # 1 at the end of the ice chute.

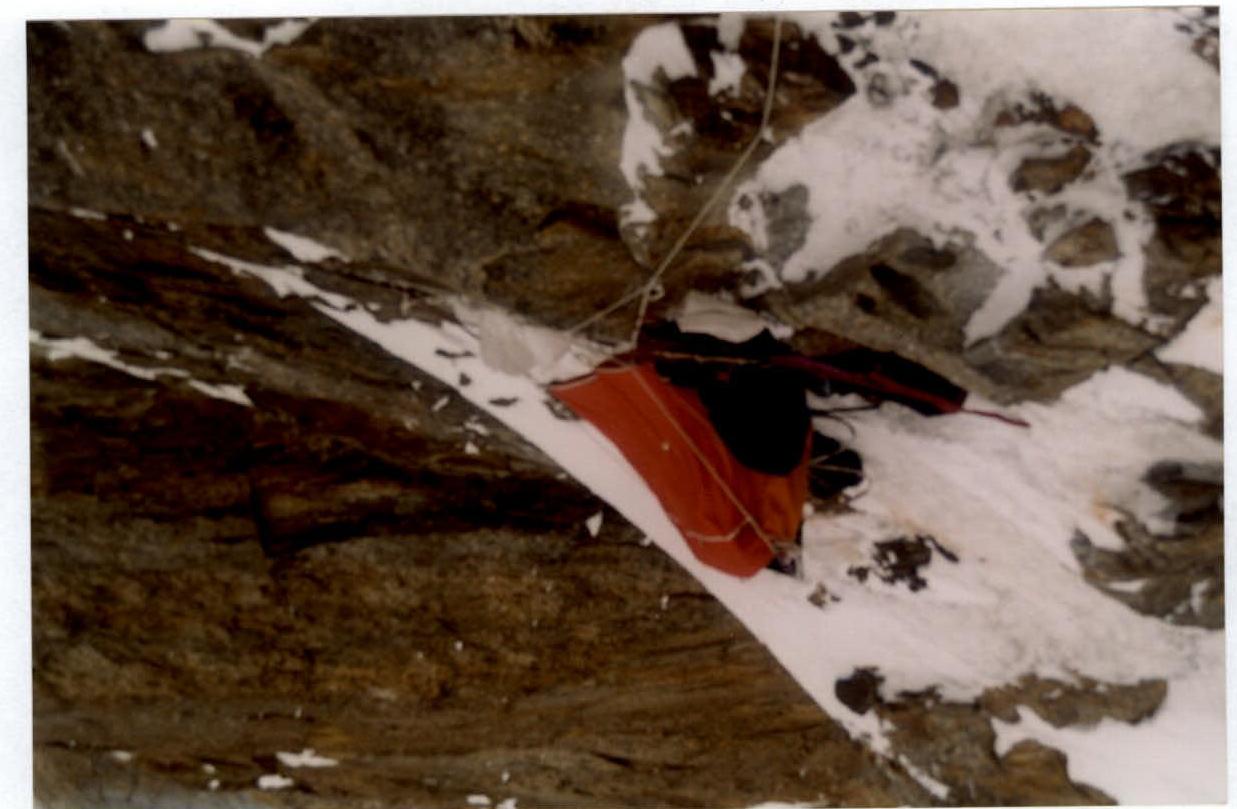

Photo # 4. Transferring loads between camps # 1 and # 2.

Photo # 5. Camp # 2.

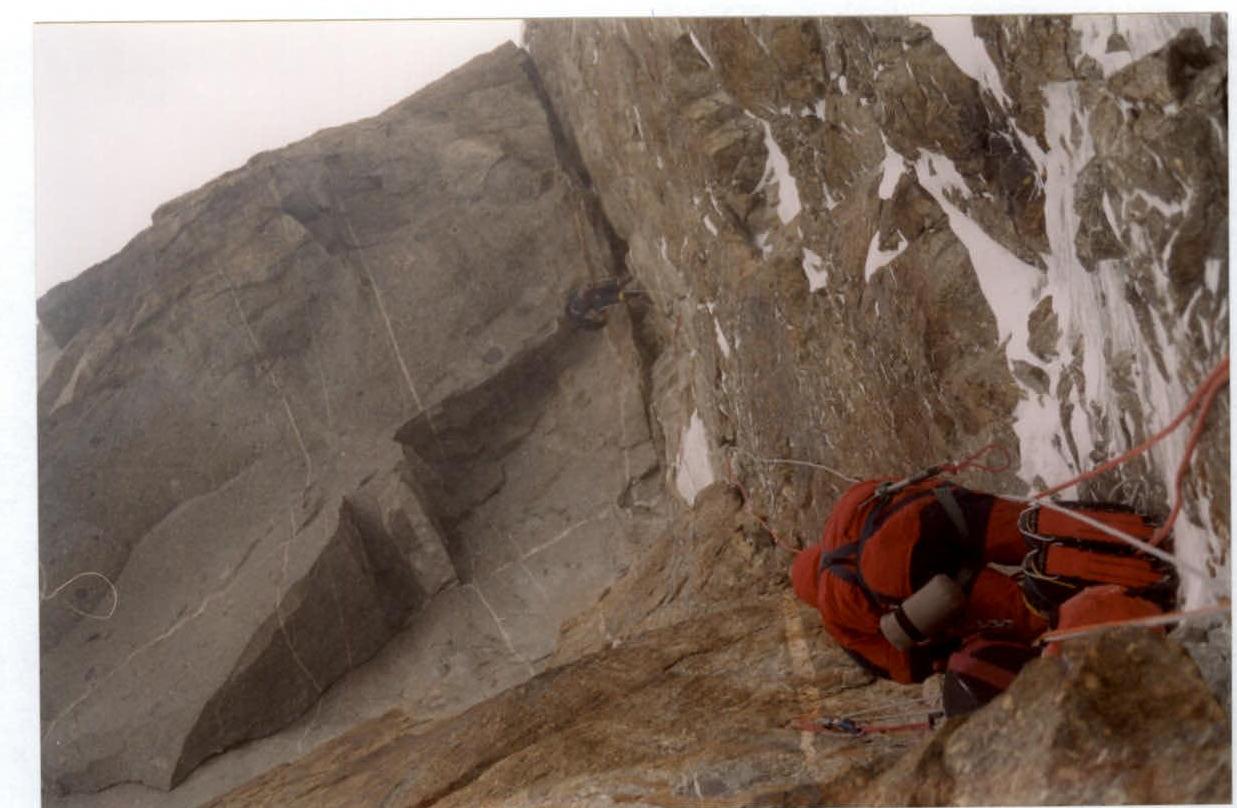

Photo # 6. Site for camp # 3.