- The ascent category — technical

- Ascent area — Fan Mountains, Pamir-Alay

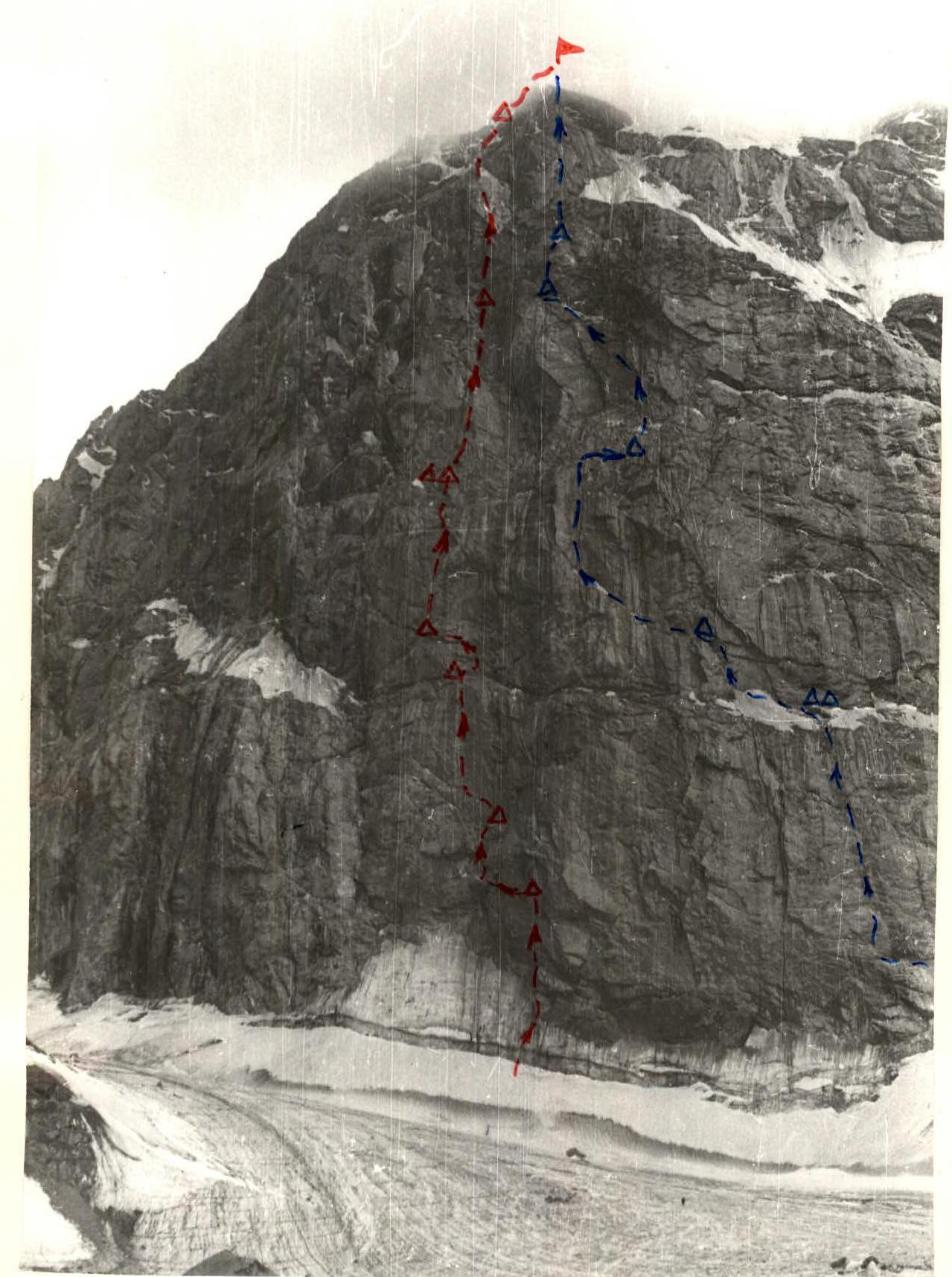

- Ascent route with indication of peaks and their elevations: via the center of the north wall of ZINDON 4800 m, first ascent.

- Proposed difficulty category — 6B

- Route characteristics: height difference 1200 m, length of sections with 5–6 difficulty category — 1089 m, average steepness — 84°

- Number of pitons and chocks used for protection and artificial aids: rock — 334 (140), ice — 42 (2), bolt — 17 (16), chocks — 49 (37)

- Number of climbing hours — 118

- Number of bivouacs and their characteristics: 8 bivouacs, including:

- sitting in a tent — 3

- semi-reclining in a tent — 4

- good tent — 1

- Team of instructors from the "Artuch" alpine camp.

- Surname, name, patronymic of the team leader, participants, and their qualifications:

- Shumilov Oleg Ivanovich — Master of Sports of the USSR — team leader

- Vekslar Valery Yakovlevich — Master of Sports of the USSR — deputy leader

- Tyulpanov Sergey Sergeevich — Candidate for Master of Sports

- Chasov Eduard Izralievich — Candidate for Master of Sports

- Fedotov Yuri Nikolaevich — Candidate for Master of Sports

- Shopin Vladimir Grigorievich — Master of Sports of the USSR

- Snetkov Evgeny Ivanovich — Master of Sports of the USSR

- Surzhik Mikhail Vladimirovich — Master of Sports of the USSR

- Team coach — Master of Sports of the USSR — Tisyachnaya Galina Grigorievna

- Date of departure and return: departure on August 8, 1977, return on August 17, 1977.

ROUTE VIA THE CENTER OF THE NORTH WALL OF ZINDON

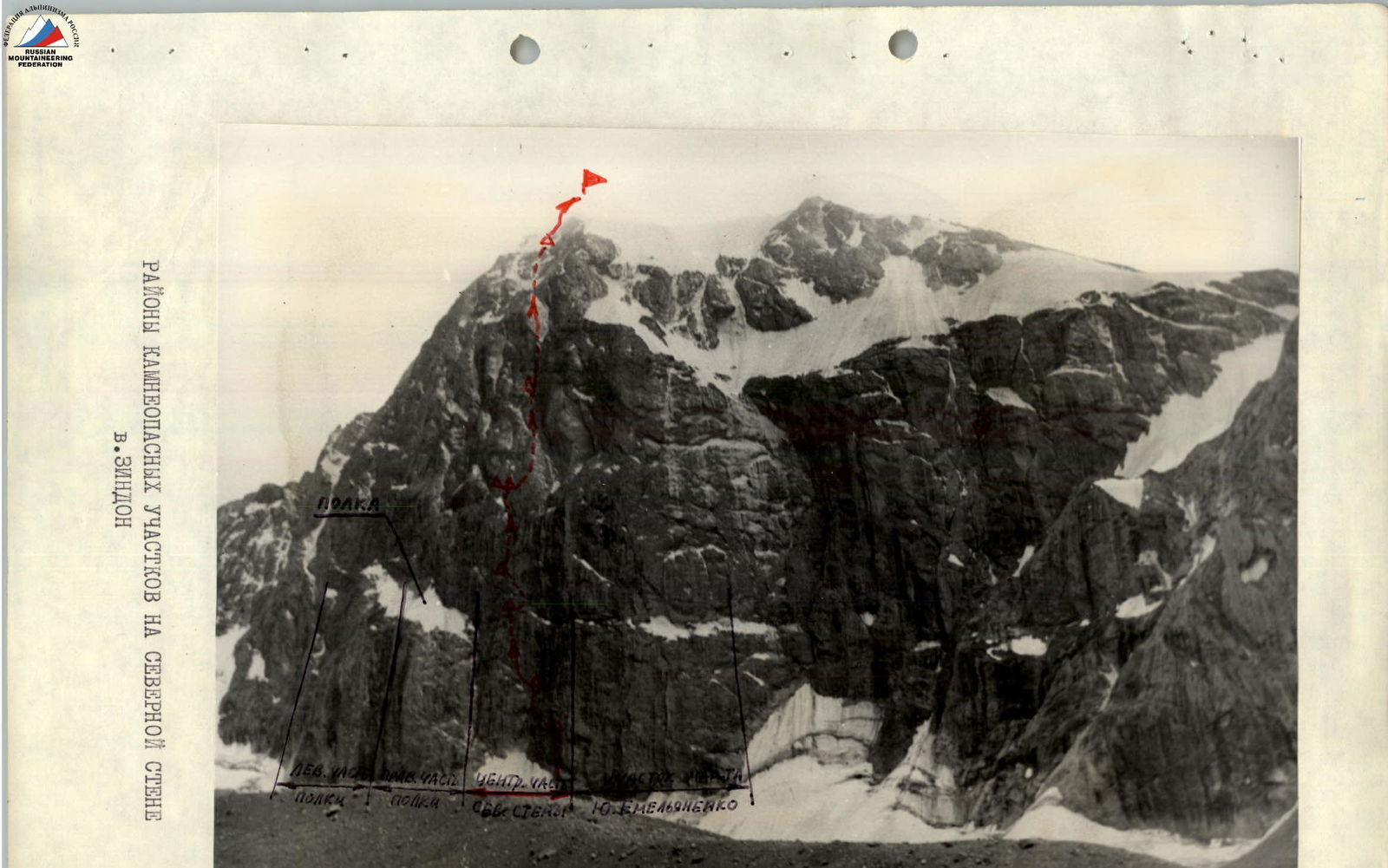

YU. EMELYANENKO'S ROUTE 1974

ROCKFALL AREAS ON THE NORTH WALL OF ZINDON

August 8

Wake-up at 6:00. Today we planned to start processing the route. It's a 1.5-hour walk from the wall to the base camp. The first pair hastily gulps down coffee, occasionally glancing at the white wall after several days of bad weather. The wall is covered with snow that hasn't had time to melt, except for the section we've chosen for our ascent. The north wall of Zindon looks imposing and austere. It's as if it's radiating cold, which is unusual for the warm region of the Fan Mountains. Nevertheless, just two days ago, a "normal" winter storm raged here. Only now do we understand why the locals named this mountain and the gorge "Zindon," which translates to "prison" in Tajik.

The central section of the north wall of Zindon, which we've chosen, looks particularly gloomy and inaccessible, as if it's been "pushed in" to the mountain's stone body. Preliminary, thorough reconnaissance of the planned route revealed the following:

- Due to the large number of cornices and the presence of a bastion in the upper part of the wall, our path should be the least rockfall-prone.

- The snow under it is the cleanest from falling stones — they are all thrown away and fly over the bergschrund line onto the glacier.

Today we need to resolve the main, fundamental question: is the lower belt of rocks on the wall passable? We've never seen such a congestion of cornices when looking through binoculars.

At 8:00, the first pair approaches the bergschrund. The bergschrund stands as a 10-meter steep wall with a meter of "negative" in the upper part. To get to the top, we have to use:

- crampons,

- ice axes,

- ladders.

The ice is not good; it shatters with lenses, but from above, as we expected, it seems like nothing is falling — that's the main thing. The ice wall above the bergschrund is steep, but in contrast to the just-passed cornice, it's overcome on front points and with step-cutting quite quickly. The latter is especially important since we have only 4 pairs of crampons. The closer we get to the wall, the more it "looms" over us. Yes, the steepness here is great. We weren't wrong in thinking that the main part of the wall is apparently steeper than 80°. After the ice, quite destroyed reddish rocks are replaced by an internal angle that leads to a slab covered with ice. This slab is a solid mirror. Neither crampons nor galoshes hold on it. Fortunately, to the right of the slab, there's a crack into which we can place channel pitons. Ice greatly complicates movement. We try different footwear: tricons, vibram, galoshes, vibram with crampons. And this is just the beginning — we haven't reached the cornices yet!

The second slab stands as a vertical wall, and the crack in the central part is filled with ice. Pitons hold poorly and melt under load. Moreover, the slab can't be passed without artificial points of support. We have to use ladders and chocks (or "zakladkhi" as we call them). However, the wall yields inch by inch. From below, it seems like the pair is standing still, but they're working continuously. They work without distraction for a minute. At 13:00, the second pair, called by radio, approaches and brings the missing equipment. It's also important that as many team members as possible get to experience the wall's steepness on the first day.

We pass a cornice on a monolithic wall and move into an internal angle that's very steep, making movement not much easier. There are still very few handholds, and now there's no crack! True, small cracks start to appear. The work is organized as follows:

- A piton is hammered in;

- A ladder is hung;

- Continuous work continues — minute by minute, hour by hour.

Under the sun's rays, the ice on the wall starts to melt, dripping from above, and the rocks become wet. It's not easier to climb, but the wall, albeit slowly, yields to us.

What can we expect? We chose this path ourselves, and now the task is to pass it. Visibility gradually worsens, and it starts to snow lightly. At times, the first pair becomes invisible from below.

By 16:00, we reach a ledge — a good sitting bivouac. We decide to finish for the day and descend to the base camp. We're very cold, and it's unclear what the weather will be like in the evening. We covered about 200 m today, including:

- 100 m of ice;

- 60 m of extremely complex rocks.

Tomorrow is a decisive day — we start passing the first belt of cornices.

August 9, 1977

The first pair departs from the base camp in complete darkness. We need to cover the processed section from the previous day and start moving further as early as possible. This is the first "problematic" section of the route. In any case, it was the subject of much discussion at the base camp: "How to pass it?" Some even suggested that it could only be passed with bolt pitons. That's not an option for us. We have only 20 bolt pitons, which is enough for 20 m of the route at most. We decide to use them only in extreme necessity when there's no other way out. For example:

- If we encounter a cornice without cracks or breaks. In other cases, we decide to use them for protection.

- Safety is paramount!

At 11:00, only observers remain at the tent. The team is all on the wall.

The first pair, after the ledge from which it's hard to tear away, passes a 10-meter rock wall covered with a thin layer of ice, then traverses onto an inclined slab. The slab is very steep, with few cracks, and they're very small. Having advanced a few meters to the left, mainly by holding onto petal pitons, the leader returns and hammers in the first bolt piton for protection. Further on, at first glance, there are no cracks, and we need to cover two meters to a small dent in the rock where we can supposedly stand. Below, the glacier is visible. The traverse goes under a cornice. What to do? We don't want to rely solely on petal pitons for protection. Let's use a bolt piton; it's more reliable. The protection is ready, and now we can move forward. Finally, we can look around the corner. It's not "honey" there either. We've never had to traverse on such terrain before. We're glad to have covered every meter. The path is very complex:

- There are no handholds or cracks;

- The steepness is very great;

- We're almost always leaning out.

We can't go up either — there's such a cornice that we'll use up all our bolt pitons.

What to do next? The cornice doesn't even mark the end of the first rock belt. And what about the second and third? From below, they don't seem simpler than the first. We decide to advance a bit further.

Finally, almost a victory! On the main negative wall, there's a crack. We can cover a few meters on ladders. The crack gradually disappears like a crack for pitons. However, on the rock, there are several rock "nodules":

- We can't hammer pitons under them;

- But we can hold onto them.

Above, a few meters higher, there's some kind of small niche, ledge, or nest. It seems like we can stand there without ladders. It's just unclear how well the "nodules" hold.

To be sure, we hammer in another bolt piton while standing on ladders. Now we can move further — the protection is there. The nest turns out to be small, and standing in it, holding onto its edges, we're still leaning out. With great difficulty, we manage to hammer in two pitons here and take in the second climber.

Above us, rocks overhang, and it's not visible where the cornice belt ends.

The path further is to the left along a gradually disappearing ledge on "leaning out" rocks. A bit further and lower, we see a pronounced inclined shelf. We still need to reach that shelf.

The path is blocked by an overhanging outer angle of black color. It's absolutely without handholds. To pass further, we can only use a pendulum.

To be sure, we hammer in two bolt pitons — and forward! The pendulum is a success, the first one on the slab!

Finally, we can hammer in several pitons without standing on ladders and secure the rappel rope.

It's already 17:00, and we've worked hard on such terrain. It's time to return to the planned bivouac site. But the most complex section of the path is behind us. Now things should go faster.

On this traverse, which is slightly longer than the rope's length (50 m), we've hammered in about 40 pitons of various types. That's almost one piton per meter!

We return to the ledge, and by our satisfied faces, the guys understand: the first "key" of the route is passed!

The bivouac is sitting and not very comfortable, but everyone sleeps without dreams. We're tired.

August 10

The first pair departs. We pass the difficult section processed yesterday to the end of the rappel and continue moving further. After the most complex traverse passed the day before, the steep rocks seem comparatively simple, although, by general standards, this section corresponds to the 5th difficulty category. From the end of the traverse, we move along steep rocks for about a rope's length. Then we exit onto a sloping ledge and approach a large stone like a ledge. Here, if we don't spare our efforts, we can arrange a decent sitting bivouac. But it's only 15:00, so we continue moving further. The second part of the group is instructed via radio to remove the previous bivouac, leave control cairn №1, and organize a bivouac at the chosen site. Above the supposed bivouac, movement goes along a three-meter wall with maximum difficulty climbing and preliminary "podtasyvanie," and then to the left along an inclined ledge, partly interrupted. This transition becomes particularly difficult because the steepness remains high — 75°, and to the right, a smooth steep wall rises without a single handhold, so we have to use cracks at the base of the ledge (right at our feet) for piton protection, and in places where it's broken, we're particularly thrown out. The traverse is exceptionally difficult. Below the ledge, there's a wide shelf that seems simpler to pass at first glance. However, it's peppered with falling stones, sometimes "greeting" us with their fall. Therefore, we choose a more difficult but safer path.

After 55 m, the ledge ends, and the path is visible vertically up along steep, smoothed slabs, partly with negative inclination and without visible cracks.

The first piton is hammered in with "podtasyvanie." We use ladders, petal pitons, and, unfortunately, bolt pitons. For the first time, we hammer in two bolt pitons to pass a negative section without cracks or handholds. But we can't cover much of the wall.

It's already 19:30. It's time to return to the bivouac site, where we decide to leave control cairn №2. We've processed over 100 m today, spending 13 climbing hours. Some "progress" compared to the previous day is possibly due to the opportunity to change the leading pair in the middle of the day. The bivouac is sitting but relatively comfortable.

August 11

The pair starts moving along the rappel ropes at 6:00 and climbs the section of the wall processed the day before. The steepness of the wall has decreased somewhat, but the rocks have become smooth and slippery. Shortening the ladder, the leader in the pair stands on a piton and manages to hammer a bolt piton into the smooth, crack-free rock 1.5 m higher and reach a small ledge about 5 cm wide and 50 cm long. Thus, we manage to gain a few meters on our wall.

After 1.5 m of ascent along the wall, the path is blocked by a cornice, which we decide to bypass by traversing to the right. We use petal pitons hammered into a crack running along the joint between the wall and the cornice. On the traverse, we have to hammer in 6 pitons over 3 m.

Due to strong tension:

- Sweat droplets roll down our foreheads;

- Fingers numb.

We link three pitons hammered into rock cracks, hang a ladder, and, pulling ourselves up on it, manage to exit onto the cornice, behind which lies a completely smooth slab.

The exhausted pair is replaced by a fresh one, which continues moving further. On the slab, using the roughness of the limestone runoff, we reach a horizontal crack after 4 m. Finally, we can hammer in a large channel piton and secure the rope. Further on, the path is blocked by the next cornice, but there's no other way. We hammer in a piton, hang a ladder, secure the rope, and finally exit into an internal angle crossing the cornice. The angle is 75° steep, the rocks are monolithic, but there are enough cracks to hammer in pitons. After 20 m, having passed another small cornice along the way, we exit onto a wall of destroyed rocks where we can organize a belay. Here, on our path, stands a wall of "bochkoobrazny" form. We hammer in a piton, hang a ladder, and after another 20 m, exit onto a ledge under the protection of a cornice. The rocks are destroyed and snow-covered. Here, we can organize a semi-reclining bivouac for the entire group. Via radio, the pair informs the comrades about the need to prepare the bivouac and the possibility of pulling up rucksacks, and then continues moving further. The cornice, 120° steep, is bypassed along a ledge to the right, then the pair passes 35 m along a slab with a 40° steepness, secures the end of the rope, and returns to the bivouac site. Here, the comrades have already organized a site and set up two tents suspended on rappel ropes. The last rucksacks are pulled up. The pair that worked ahead is treated to hot tea, and everyone goes to sleep. It's already 21:00. We covered about 100 m of the path today and secured rappel ropes further. The day was very difficult; we passed a very steep section of the route with many cornices.

August 12

We depart at 7:00. Along a destroyed slab, after 30 m, the pair approaches an overhang. Under the overhang, a place for one tent is visible. Above, as far as the eye can see, there's only a vertical wall and a series of overhangs. But there's no way around it to the right or left. The path is unambiguous — only up! The pair starts working. We use the techniques developed over the previous days to pass cornices, now almost automatically:

- Hammer in a piton, then a second one into a crack at the edge of the overhang and the wall;

- Hang a ladder, then a second one;

- Finally, the head appears over the right edge of the cornice.

Another meter — and we can catch our breath, rest on a smooth slab. We secure the rope and organize a belay point to pass the next section. This section doesn't inspire any illusions about quick passage. Above us looms a wall with a crack. After 20 m, the crack is interrupted by a cornice, which we bypass to the right. Movement on this section is on a continuous steep wall, so we widely use ladders as the only support for our feet. Only occasionally can we use small protrusions on the wall for support. As points of support with a crack, we widely use chocks, which are very effective in passing this section, especially with many cornices. A small wall, then a cornice, and after another wall, another cornice.

But it's already evening — 21:00. The "evening" pair secures the rope and descends to a ledge over the overhang.

Considering the complexity of the further path, during the day, the pair radioed the comrades to transfer one tent to a new bivouac site. We decide to leave a control cairn here. The transfer of one tent is due to saving time for the forward pair the next day, as movement even along rappel ropes takes quite a lot of time.

At the new site, four of us, designated to work first the next day, settle in. This is the first separate bivouac of the group. Will there be more such bivouacs ahead?

August 13

At 6:00, the "morning" pair moves forward. Having passed 40 m along the rappel ropes, it approaches an overhanging cornice. After passing the cornice, a slab with a crack of 15 m stands in the way, then a steep wall with a crack of 8 m, which, like many others, is passed "zальцyгом." The crack turns slightly to the right and leads to an internal angle with a crevice. Above, a huge cornice is visible, composed of red rocks and formed by two overhanging slabs at an angle to each other. On the left side of the cornice, ice runoff and overhanging icicles are visible. We decide to move to the right edge of the cornice along a slab where a fairly wide crack is visible, about 15 m long, leading to an angle of two overhangs.

In this angle of two overhangs, an exit from under the cornice is possible, and thus, the problem of passing this section, which worried us so much from below, will be solved. The cornice — a giant — is passed using the entire arsenal of mountaineering techniques along a crack in its ceiling. This required all the physical and moral strength of the pair working on this section. Finally, the cornice is passed! The pair radios down that ahead, shelves are visible where a bivouac can be organized. Work begins on pulling up rucksacks. But it's already getting dark. The pair moves another 8 m along a shelf consisting of destroyed rocks, and then 12 m along "barany lbam," secures the end of the rappel rope, and helps comrades with pulling up rucksacks and organizing a bivouac.

21:00. Work gradually dies down. This time, we manage to set up two tents side by side and organize a semi-reclining bivouac. We covered about 100 of the most difficult meters of the path today. The two pairs working ahead are very tired. We try to lay them down as comfortably as possible for rest.

August 14

We depart a bit later than usual — at 8:00, but that's understandable given the previous day's difficulty. First, we pass destroyed, icy rocks with a 50° steepness over 40 m, and then the steepness increases to 85°. The rocks are now composed of large blocks, with icy cracks between them. Movement initially goes slightly to the left, then zigzags to the right and back to the left. This section ends after 45 m before a vertical wall of destroyed rocks, 20 m high. We move extremely cautiously, constantly making "kosye" rappel ropes to eliminate the possibility of knocking stones onto each other. Behind the destroyed rocks, an 8-meter overhanging wall stands. Passing the wall is extremely difficult. Pitons are hammered in one after another. Finally, the wall is passed, and we exit onto a rock, not clearly defined, ridge or outer angle with highly smoothed rocks. The rocks are gray, marbleized. On the ridge, there's practically not a single crack; only at the base, there's a diagonal ledge ending in a runoff on destroyed rocks.

It's getting dark. Hands are freezing, especially where ice has accumulated in the cracks. However, such work has become familiar and doesn't evoke special emotions. We try to use mainly petal pitons. Finally, the 85-meter rock ridge is passed, and before us, in all its inaccessibility, stands a wall with a chimney turning into a wide crack. The chimney and crack are abundantly covered with ice. There's no point in moving further, so we return to the bivouacs. The mood is cheerful since we covered about 200 m today.

It's already 20:00. We have dinner and settle in for the night. At the team's request, to reduce psychological stress on the route, we talk about modern Japan (we agreed last year to prepare several presentations on different topics unrelated to mountaineering to avoid being too disconnected from the "real world").

August 15

We rise early, and at 7:00, the forward pair continues moving forward. Simultaneously, we give the command to dismantle the bivouac, pack rucksacks, and wait for the signal from the forward pair about the possibility of advancing to the next bivouac site. Behind the rock ridge, the wall seems to be inside the entire massif, so despite the midday, the sun doesn't penetrate here, and it's quite cold. The entire section ahead is steep and even negative — the rocks are covered with ice. However, there's an opportunity to hammer in thin universal and channel pitons. Movement initially goes along a 25-meter chimney. We have to spend a long time chiseling ice to reliably organize piton protection. Movement is carried out according to the scheme:

- Piton,

- Ladder,

- and so on, continuously moving forward.

Finally, after intense work, we reach the end of the chimney, ending in a small ledge. Further on, a short ridge is visible. A wide crack leads to it from the ledge, traversing to the right. Although the crack is wide, we have to move very cautiously since it's filled with ice, like the chimney.

Movement is as difficult as on the chimney. We constantly have to:

- Chisel ice,

- Clean cracks from it,

- Hammer in pitons.

But even after hammering in pitons, standing on a ladder, we feel that the piton "floats" slightly under the load.

After 20–25 m, the crack is passed. Here, we take a short rest and discuss the further direction of movement.

There's no significant relief after the crack, as it seemed from below. We still need to overcome a 4-meter negative wall with an overhang. The wall is made of monoliths, partly smoothed by water runoff. It's good that it's quite dry now, although, as before, the crack we're moving along is filled with ice.

We pass the wall along an implicit internal angle. Movement on this section is like an "equilibrist" working on freely hanging ladders. After "circus" work on ladders with alternating ice chiseling, piton hammering, and hanging artificial supports, the wall is passed.

We exit onto a 1.5-meter shelf where, apparently, we can organize a bivouac. The pair radios down to the comrades about the need to redeploy. Here, we plan to leave control cairn №4.

Only in the evening, the last group members pull up the remaining rucksacks to the bivouac site. Meanwhile, the tents are already hung, and the primus stoves are buzzing, with hot tea ready.

Another working day is over. We worked for 12 hours today. At the bivouac, we have a conversation about self-control in sports.

August 16

The next leading pair gets ready even in the dark. The air is filled with the unspoken tension of being close to the summit, although we still have to work hard to get there. The first pair departs at 6:00. We pass 35 m of red blocks with an 85° steepness, then movement goes along a slab with wide cracks. This section was processed yesterday. Here, we widely used chocks as artificial points of support. After 43 m, we approach a wall covered with a layer of ice. The steepness of the wall is somewhat less than the previous section, but ice complicates movement. On this section, for the first time since the start of the wall's passage, we use ice pitons. Passing this section is very difficult, but the proximity of the summit makes everyone focused. Finally, we exit onto a ledge filled with ice. Ahead, the further path is clearly visible — a crack filled with ice runoff. The forward pair's movement is measured, and meter by meter, it advances forward. Soon, the steepness of the rocks decreases, and we exit onto a slab consisting of stones frozen into ice. After 85 m, we reach a site where we can organize a bivouac. We set up tents on a laid-out platform, which takes us 1.5 hours to prepare. Ahead, the pre-summit rocks are already visible. The "evening" pair hangs two rappel ropes higher up the slope and returns to the tents. The mood is cheerful among everyone.

August 17

Due to the proximity of the summit, we don't depart as early as on previous days. Everyone has accumulated fatigue from the ascent, so we start moving at 8:00.

We move initially along "barany lbam" covered with snow and with ice-filled cracks. Then we exit onto a snow-ice ridge. Protection is piton; the ice is smooth. We have to move cautiously, cutting steps. Then the slope becomes steeper. The ice becomes ice runoff; protection becomes even more thorough, and we exit onto a snow slope covered with an ice crust, leading to the summit. 12:00. The weather is good. We take photos as a full team on the summit, with the Chimtarga peak in the background.

From the cairn, we retrieve a note left by a team from the Armed Forces of Moscow city, who ascended the north wall of Zindon (via the route of the "Trud" DSO team from Moscow under Yu. Emelyanenko's leadership, 1974).

The mood is excellent. But we can't relax. There's a lot of sad statistics related to "easy descents" after passing complex routes.

The descent is familiar since we did a reconnaissance and training ascent along the north wall via the "Trud" DSO team's route from Moscow — 6B category — a month ago. The only thing that worries us is the abundance of ice along the descent path between Zindon and SOAN peaks.

But after 6 hours, we're already at the observers' tents. We report via radio to the camp that our ascent is complete, and the next day, we head down... "Farewell, Zindon!"

GENERAL CHARACTERISTICS OF THE ROUTE. The north wall of Zindon is a slope with an average steepness of about 80–85° and a length of over 1000 m. The route is logical and varied in relief forms, including rock steep sections, cornices, and snow-ice slopes. This route is complex throughout its entire length and requires climbers to master the entire arsenal of mountaineering techniques.

The average steepness of rock sections is more than 80°, but many sections are steep or close to it. Significant difficulties during the wall's passage are created by ice runoff on slab-like sections of the route, which clogs all cracks, complicating climbing and protection.

The route requires good physical and moral-volitional preparation and can be recommended to a strong group with excellent rock climbers.

Most of the route is protected by a system of powerful cornices, making the route and bivouacs practically safe from accidental rockfall. The only rockfall-prone section of the route is the snow slope and the bergschrund area. This section requires increased attention.

Given the need for a large number of pitons, carabiners, and ladders, it's advisable to have lightweight equipment on the route.

Comparing the route via the center of Zindon's north wall with the previously passed route along this wall by our team, as well as with other 6B category routes passed by the team and its members at different times, we can confidently say that in terms of the steepness of individual sections and the overall steepness of the entire route, as well as the number of sections with maximum difficulty climbing, it significantly surpasses them, making it a route of the highest difficulty category.

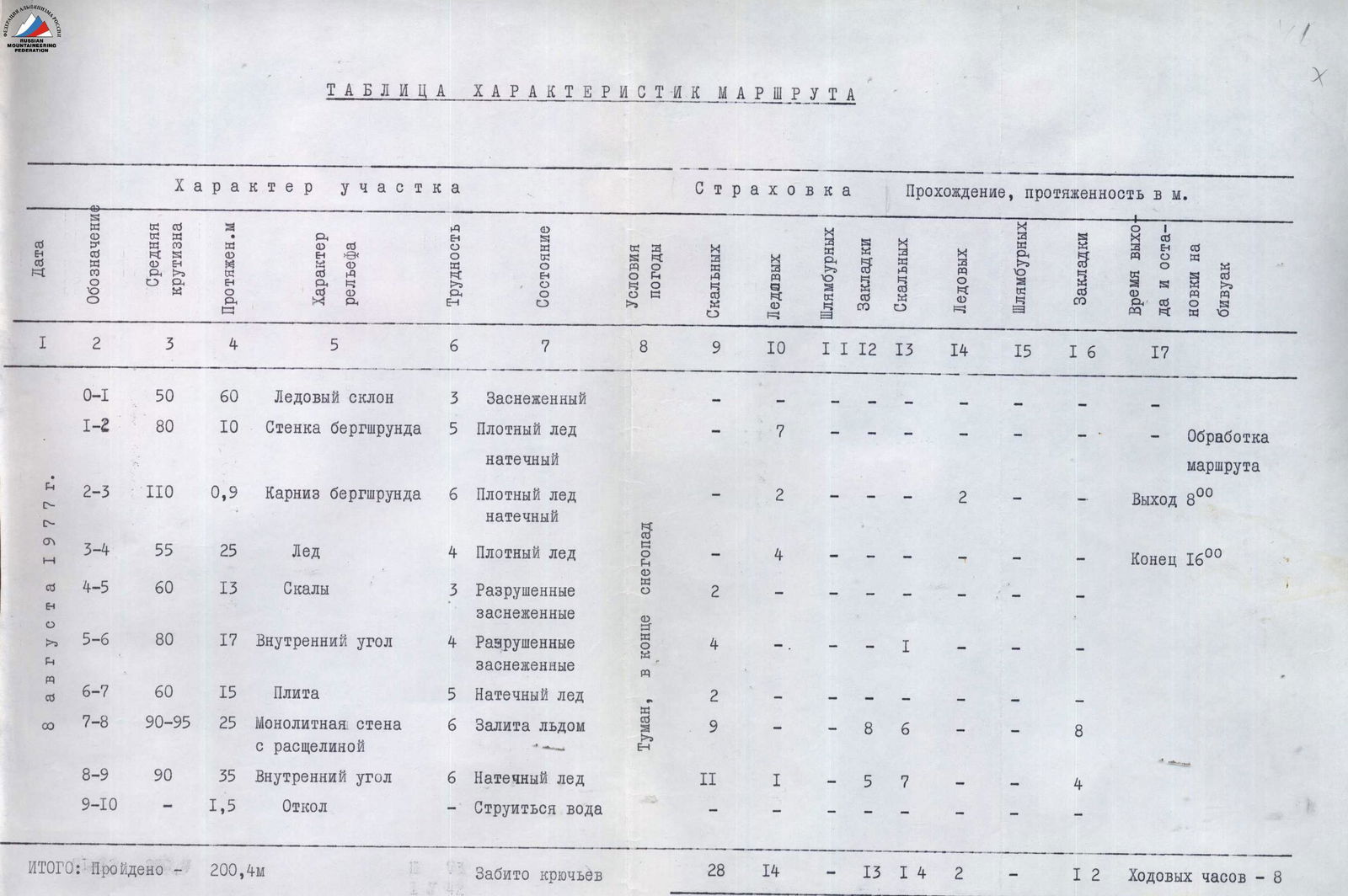

| Date | Designation | Average steepness, ° | Length, m | Character of the section | Relief character | Difficulty | State | Weather conditions | Pitons hammered: rock, pcs. | Pitons hammered: ice, pcs. | Pitons hammered: bolt, pcs. | Chocks hammered, pcs. | Passage length: rock, m | Passage length: ice, m | Passage length: bolt, m | Passage length: chocks, m | Time of departure and bivouac |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8 | R0–R1 | 50 | 60 | Ice slope | 3 | Snowy | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | Start 6:00 | ||

| Aug. | R1–R2 | 80 | 10 | Bergschrund wall | 5 | Dense ice, ice runoff | — | 7 | — | — | — | — | — | — | Route processing | ||

| R2–R3 | 110 | 0.9 | Bergschrund cornice | 6 | Dense ice, ice runoff | — | 2 | — | — | 2 | 2 | — | — | Departure 8:00 | |||

| 1977 | R3–R4 | 55 | 25 | Ice | 4 | Dense ice | Fog, snow at the end | — | 4 | — | — | — | — | — | — | End 16:00 | |

| R4–R5 | 60 | 13 | Rocks | 3 | Destroyed, snowy | — | 2 | — | — | — | — | — | — | ||||

| R5–R6 | 80 | 17 | Internal angle | 4 | Destroyed, snowy | — | 4 | — | — | — | — | — | — | ||||

| R6–R7 | 60 | 15 | Slab | 5 | Ice runoff | — | 2 | — | — | — | — | — | — | ||||

| R7–R8 | 90–95 | 25 | Monolithic wall with a crack | 6 | Filled with ice | — | 9 | — | — | — | — | — | — | ||||

| R8–R9 | 90 | 35 | Internal angle | 6 | Ice runoff | 11 | 1 | 5 | 7 | — | — | — | 4 | ||||

| R9–R10 | — | 1.5 | Ledge | — | Water is seeping | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | ||||

| TOTAL: Covered — 200.4 m. Pitons hammered: rock — 28, ice — 14, bolt — 13, chocks — 1. Covered on: rocks — 4 m, ice — 2 m, bolt — 1 m, chocks — 2 m. Climbing hours — 8. |